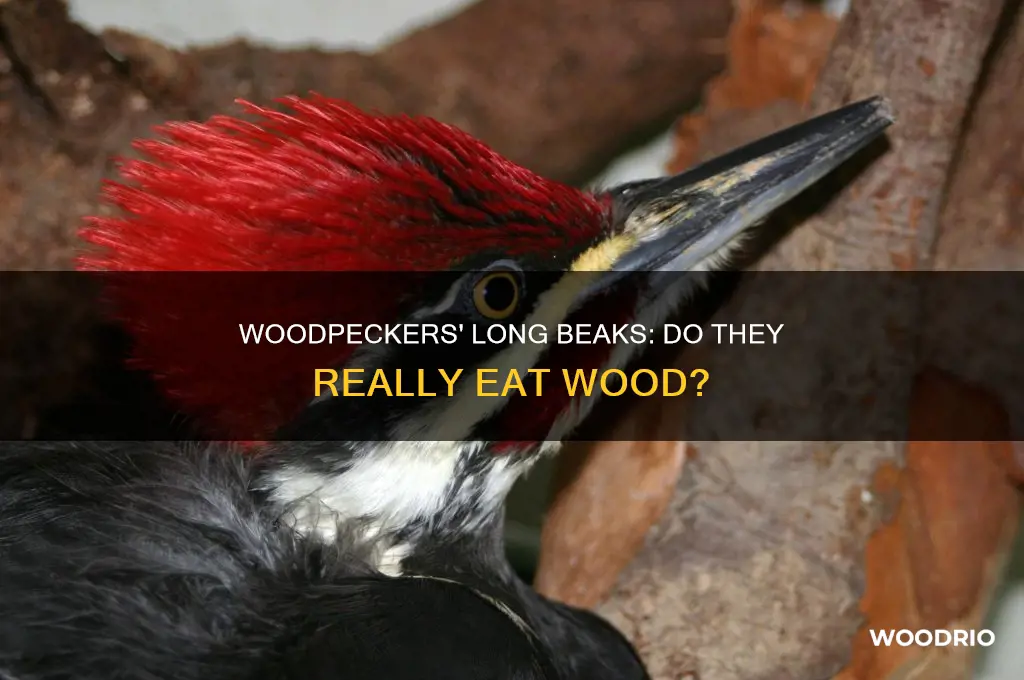

Woodpeckers are often associated with their distinctive drumming on trees, but a common misconception is that they eat wood with their long, slender beaks. In reality, woodpeckers do not consume wood as a food source. Instead, their strong, chisel-like beaks are adapted for drilling into trees to search for insects, larvae, and eggs hidden beneath the bark. The rhythmic drumming also serves to establish territory and attract mates. While their beaks are perfectly suited for excavating wood, woodpeckers primarily rely on a diet of insects, nuts, seeds, and fruits, making their relationship with trees more about foraging than feeding on the wood itself.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Diet | Woodpeckers primarily eat insects, larvae, nuts, fruits, and sap, not wood. |

| Beak Use | Their long, chisel-like beaks are used for drilling into trees to find insects or create nesting holes, not for eating wood. |

| Tongue Function | Woodpeckers have long, sticky tongues that extract insects from deep within tree bark, not for consuming wood. |

| Wood Consumption | Woodpeckers do not digest wood; their digestive systems are adapted for processing insects and other food sources. |

| Drumming Behavior | The drumming sound they make is created by rapidly pecking wood to establish territory or attract mates, not for eating. |

| Physical Adaptation | Their skulls and beaks are reinforced to withstand the impact of pecking, but this is unrelated to consuming wood. |

| Ecological Role | Woodpeckers help control insect populations and create cavities that benefit other wildlife, not by eating wood. |

Explore related products

$13.99 $18.15

What You'll Learn

Woodpecker Beak Anatomy: Structure and Function

Woodpeckers do not eat wood with their beaks; instead, they use their specialized beaks to drill into trees to extract insects, larvae, and sap. This common misconception arises from their distinctive drumming behavior, which serves territorial and communicative purposes rather than foraging for wood as a food source. Understanding the anatomy of a woodpecker’s beak reveals how it is uniquely adapted for these functions, combining strength, precision, and shock absorption in a way no other bird’s beak can.

The woodpecker’s beak is a marvel of evolutionary engineering, composed of a hard, chisel-like tip made of keratin, the same material as human fingernails. This tip is sharply pointed and slightly curved downward, allowing it to penetrate wood with minimal effort. Unlike most birds, a woodpecker’s beak has a longer upper mandible that overlaps the lower one, providing a self-sharpening mechanism as the bird pecks. This design ensures the beak remains effective even after repeated impact, which can occur at speeds of up to 15 miles per hour and with a force of 1,200 g’s—enough to cause brain injury in humans.

Beneath the surface, the woodpecker’s beak is supported by a robust skeletal structure. The skull features a reinforced bone structure, including a spongy bone layer that acts as a shock absorber, distributing the force of each peck away from the brain. Additionally, the beak is attached to the skull via a flexible hinge-like structure, further reducing the risk of injury. This combination of hardness and flexibility is critical for the bird’s survival, enabling it to drum on trees for hours without harm.

To protect their brains from the constant pounding, woodpeckers have evolved a unique tongue structure. Their tongues wrap around the skull, acting as an additional shock absorber and preventing brain damage. The tongue also serves a practical purpose in foraging, as it is long, barbed, and sticky, allowing the bird to extract insects from deep within tree bark. This dual functionality highlights the interconnectedness of the woodpecker’s anatomy, where each feature complements the others to support its specialized lifestyle.

In practical terms, observing woodpecker beak anatomy offers insights into biomimicry—the practice of emulating nature’s designs for human innovation. Engineers have studied woodpecker skulls to develop shock-absorbing materials for sports helmets and construction tools. For bird enthusiasts, understanding these adaptations deepens appreciation for the species and informs conservation efforts, as habitat loss threatens many woodpecker populations. By examining the beak’s structure and function, we gain not only biological knowledge but also inspiration for solving real-world challenges.

Does Wood Length Affect Compression Strength? Breaking Down the Science

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$9.99 $11.54

Wood-Eating Myth: Do Woodpeckers Actually Consume Wood?

Woodpeckers are often associated with their distinctive drumming on trees, a behavior that has led to the widespread belief that they eat wood. However, this is a misconception. Woodpeckers do not consume wood as a primary food source. Their long, slender beaks are not designed for chewing wood but rather for drilling into trees to access insects, larvae, and sap, which form the bulk of their diet. This clarification is crucial for understanding the ecological role of woodpeckers and dispelling the wood-eating myth.

To explore this further, consider the anatomy of a woodpecker’s beak and tongue. Their beaks are chisel-like, adapted for pecking and excavating, not for grinding or digesting woody material. Additionally, their tongues are remarkably long and barbed, allowing them to extract insects from deep within tree bark. This specialized anatomy underscores their role as insectivores, not xylophages (wood-eaters). For instance, a single woodpecker can consume thousands of wood-boring beetle larvae annually, making them vital for forest health by controlling pest populations.

From a practical standpoint, understanding that woodpeckers do not eat wood can help homeowners and conservationists address woodpecker-related issues more effectively. If woodpeckers are drumming on your property, it’s likely because they’ve detected insects in the wood, not because they’re hungry for the wood itself. To deter them, focus on eliminating insect infestations rather than trying to protect the wood directly. For example, treating affected trees with insecticides or wrapping them with protective netting can reduce woodpecker activity without harming the birds.

Comparatively, other bird species, like certain parrots, have beaks adapted for cracking seeds or nuts, while woodpeckers’ beaks are uniquely suited for their insectivorous lifestyle. This distinction highlights the importance of observing and understanding animal behaviors before drawing conclusions. By recognizing the true dietary habits of woodpeckers, we can appreciate their ecological value and coexist with them more harmoniously.

In conclusion, the idea that woodpeckers eat wood is a myth rooted in their tree-drumming behavior. Their beaks and tongues are specialized tools for accessing insects, not for consuming wood. By focusing on their actual dietary needs and ecological roles, we can better protect both woodpeckers and the forests they inhabit. This knowledge not only enriches our understanding of wildlife but also guides practical solutions for managing human-woodpecker interactions.

Boiling Wooden Spoons: The Ultimate Guide to Safe Sterilization

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Diet of Woodpeckers: Insects, Sap, and Seeds

Woodpeckers are often associated with their distinctive drumming on trees, but their diet is far more diverse than their name suggests. While they don’t eat wood directly, their long, chisel-like beaks are perfectly adapted for extracting insects hiding beneath bark. This behavior not only provides them with a primary food source but also plays a crucial role in forest health by controlling insect populations. For example, a single woodpecker can consume thousands of wood-boring beetles annually, protecting trees from infestation.

Beyond insects, woodpeckers are opportunistic feeders with a diet that includes sap and seeds. Sap, in particular, is a seasonal treat, especially during winter when insects are scarce. Woodpeckers create small holes in trees to access sap, which flows freely in certain species like maples. This sap provides essential sugars and nutrients, helping them survive colder months. Interestingly, some woodpeckers, like the sapsuckers, have specialized feeding habits, creating sap wells that also attract other birds and insects, creating mini-ecosystems around their feeding sites.

Seeds are another vital component of a woodpecker’s diet, especially for species that inhabit woodlands or urban areas. Acorn woodpeckers, for instance, are known for their remarkable caching behavior, storing thousands of acorns in granaries—holes drilled into trees or wooden structures. These stored seeds serve as a reliable food source during lean times and are often shared within family groups. For bird enthusiasts, providing suet feeders or seed cakes can attract woodpeckers, offering a close-up view of their feeding habits while supplementing their natural diet.

Understanding the diet of woodpeckers highlights their adaptability and ecological importance. From insect control to sap extraction and seed caching, these birds play multifaceted roles in their habitats. For those looking to support woodpeckers, planting native trees that attract insects or setting up feeders with suet and seeds can make a significant difference. By catering to their dietary needs, we not only aid these fascinating birds but also contribute to the health of the ecosystems they inhabit.

Durability of Wood Retaining Walls: Lifespan and Maintenance Tips

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Beak Usage: Drumming, Foraging, and Nesting Habits

Woodpeckers do not eat wood with their beaks, despite the common misconception. Instead, their beaks serve as versatile tools for drumming, foraging, and nesting, each function finely tuned by evolution. Drumming, a rapid pecking on resonant surfaces like trees or even metal, is primarily a territorial and mating display. Woodpeckers can drum at speeds of up to 20 pecks per second, creating a distinctive sound that echoes through forests. This behavior not only signals dominance but also helps attract mates by demonstrating strength and vitality.

Foraging, on the other hand, showcases the beak’s precision and adaptability. Woodpeckers use their chisel-like beaks to excavate bark, uncovering insects such as ants, beetles, and larvae. Their long, sticky tongues, which can extend up to 4 inches, are then employed to extract prey from deep crevices. Interestingly, some species, like the acorn woodpecker, also use their beaks to drill holes in wood to store acorns, a behavior known as caching. This dual-purpose use of the beak highlights its role as both a tool and a weapon in the woodpecker’s survival strategy.

Nesting habits further illustrate the beak’s importance. Woodpeckers excavate nest cavities in dead or decaying trees, a process that can take weeks. The male typically initiates the excavation, using his beak to chip away wood until a suitable chamber is formed. These cavities not only provide shelter but also serve as safe havens for raising offspring. Once abandoned, these holes often become homes for other bird species, underscoring the woodpecker’s ecological impact.

To observe these behaviors in action, consider visiting a deciduous or coniferous forest during the early morning or late afternoon, when woodpeckers are most active. Binoculars and a keen ear for drumming sounds can enhance your experience. For those interested in attracting woodpeckers to their backyard, providing suet feeders or deadwood piles can encourage foraging and nesting activities. However, avoid placing feeders near windows to prevent accidental collisions, a common hazard for these fast-flying birds.

In summary, the woodpecker’s beak is a marvel of specialization, optimized for drumming, foraging, and nesting. By understanding these behaviors, we gain insight into the intricate ways woodpeckers interact with their environment. Whether you’re a birdwatcher, a naturalist, or simply curious, observing these habits offers a deeper appreciation for the adaptability and resourcefulness of these fascinating birds.

Do Daddy Long Legs Burrow in Wood? Unveiling the Truth

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Woodpecker Digestion: How They Process Non-Wood Food Items

Woodpeckers are renowned for their ability to drill into trees with their long, chisel-like beaks, but contrary to popular belief, they do not eat wood as a primary food source. Instead, their foraging behavior targets the insects and larvae hidden within the wood. This raises an intriguing question: how do woodpeckers digest non-wood food items, such as ants, beetles, and berries, which constitute a significant portion of their diet? Understanding their digestive system provides insight into their remarkable adaptability.

The digestive process begins in the woodpecker’s mouth, where their sticky, barbed tongue extracts insects from deep crevices. Unlike humans, woodpeckers lack teeth, so food passes directly to the crop, a pouch-like structure that stores and softens it. From there, the food moves to the proventriculus, often called the "true stomach," where digestive enzymes break down proteins and fats. This stage is crucial for processing high-protein insect meals, which are a staple for many woodpecker species. For example, the acorn woodpecker consumes large quantities of ants, relying on its efficient digestive system to extract nutrients swiftly.

One of the most fascinating aspects of woodpecker digestion is their gizzard, a muscular organ that grinds food into smaller particles. While the gizzard is not as robust as those of seed-eating birds, it still plays a vital role in processing tougher food items, such as nuts or hard-bodied insects. Interestingly, woodpeckers often ingest small stones or grit, which accumulate in the gizzard to aid mechanical breakdown. This behavior is particularly observed in species like the red-bellied woodpecker, which supplements its diet with acorns and seeds during winter months.

After the gizzard, food moves to the intestines, where nutrients are absorbed into the bloodstream. Woodpeckers have a relatively short digestive tract compared to herbivores, reflecting their insectivorous diet. However, some species, such as the northern flicker, consume fruits and berries, which require additional enzymes to break down sugars and fibers. This dietary flexibility highlights the woodpecker’s ability to adapt its digestive processes based on food availability.

Practical observations of woodpecker digestion can inform conservation efforts and backyard bird feeding. For instance, providing suet cakes—high-fat, insect-rich blocks—mimics their natural diet and supports their energy needs, especially during colder months. Avoid offering whole nuts or large seeds without a means of cracking them, as woodpeckers’ gizzards are not equipped to handle such items efficiently. By understanding their digestive capabilities, we can better cater to these fascinating birds and ensure their nutritional needs are met in human-altered environments.

Optimal Clamping Time for Wood Glue: A Comprehensive Guide

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, woodpeckers do not eat wood. Their long, chisel-like beaks are used to drill into trees to find insects, larvae, and other prey living inside the wood.

Woodpeckers primarily feed on insects, larvae, spiders, and other arthropods found in trees. Some species also eat fruits, nuts, sap, and occasionally small vertebrates like lizards or bird eggs.

Woodpeckers peck on wood to locate and extract insects, create nesting cavities, or establish territory by making drumming sounds. Their strong beaks and shock-absorbing skull structures allow them to do this without injury.