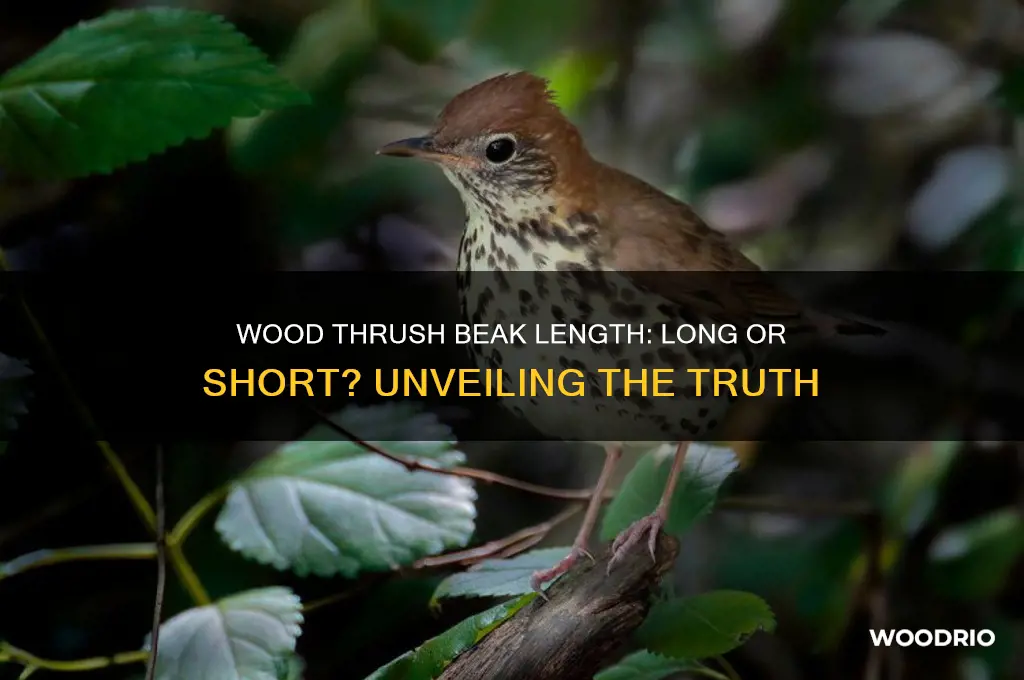

The wood thrush, a medium-sized bird known for its rich, flute-like song, is often admired for its striking appearance and melodious calls. While its beak is not particularly long compared to some other bird species, it is well-suited to its diet and habitat. The wood thrush primarily feeds on insects, worms, and berries, and its beak is designed to efficiently forage on the forest floor, probing the soil and leaf litter for prey. Although not elongated, the beak’s shape and strength allow the bird to thrive in its woodland environment, making it a fascinating subject for those curious about avian adaptations.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Wood Thrush Beak Length Comparison

The wood thrush, a bird celebrated for its ethereal song, often sparks curiosity about its physical traits, particularly its beak. A comparison of beak lengths across species reveals that the wood thrush’s beak is neither exceptionally long nor short. Measuring approximately 1.5 to 1.8 centimeters, it falls within the average range for medium-sized thrushes. This length is adapted for its omnivorous diet, allowing it to efficiently forage for insects, snails, and berries on the forest floor.

To contextualize, consider the American robin, a close relative with a slightly longer beak (2.0–2.5 cm), suited for earthworm probing. In contrast, the eastern bluebird’s beak is shorter (1.2–1.5 cm), reflecting its preference for airborne insects. The wood thrush’s beak, therefore, occupies a middle ground, optimized for versatility rather than specialization.

For birdwatchers aiming to identify wood thrushes, focus on beak shape as much as length. Its straight, slender profile distinguishes it from the more curved beaks of warblers or the thicker bills of tanagers. Pair this observation with its spotted breast and rich, flute-like song for accurate field identification.

Practical tip: Use a field guide or app with size comparisons to gauge beak length relative to other thrushes. Note that juveniles may have slightly shorter beaks, which lengthen as they mature. This detail aids in distinguishing age groups during breeding seasons.

In summary, the wood thrush’s beak length is unremarkable in isolation but becomes meaningful when compared to its ecological niche and relatives. Its moderate size underscores its role as a generalist forager, blending adaptability with precision in its woodland habitat.

Woods Hole to Martha's Vineyard Ferry: Duration and Travel Tips

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$26.99 $32.99

Beak Shape and Function Analysis

The wood thrush, a bird celebrated for its ethereal song, presents a beak that is neither exceptionally long nor short but rather a study in precision and purpose. Measuring approximately 1.5 to 1.8 centimeters in length, its beak is straight, slender, and slightly curved at the tip, a design that reflects its primary function: foraging for insects and invertebrates in leaf litter. This shape allows the bird to probe soil and decaying vegetation with minimal effort, extracting prey with surgical accuracy. Unlike the elongated beaks of nectar feeders or the robust ones of seed crackers, the wood thrush’s beak is a testament to the principle that form follows function in nature.

Analyzing beak shape through a comparative lens reveals how small variations serve distinct ecological roles. For instance, the wood thrush’s beak contrasts sharply with that of the long-billed thrasher, whose extended beak is adapted for deeper probing in arid soils. Similarly, the shorter, more conical beak of the American robin is optimized for consuming fruits and berries. The wood thrush’s intermediate beak length, however, strikes a balance, enabling it to exploit a niche where insects are abundant but competition is moderate. This adaptation underscores the evolutionary trade-offs between specialization and versatility in avian feeding strategies.

To understand the functional implications of beak shape, consider the mechanics of foraging. The wood thrush’s slender beak reduces resistance when piercing soft substrates, conserving energy during prolonged feeding sessions. Its slight curvature aids in gripping and manipulating prey, a feature particularly useful when handling wriggling insects. Observing this bird in action provides a practical lesson in biomechanics: beak design is not merely about reaching food but also about efficiently securing and consuming it. For birdwatchers, noting these details can enhance identification skills and deepen appreciation for avian adaptations.

A persuasive argument for the significance of beak shape lies in its role as an indicator of ecological health. The wood thrush’s beak is finely tuned to its forest habitat, where leaf litter teems with invertebrates. Habitat degradation, such as deforestation or excessive leaf removal, disrupts this delicate balance, reducing food availability and threatening the bird’s survival. Conservation efforts must therefore prioritize preserving intact forest floors, ensuring that the wood thrush’s beak remains a tool of sustenance rather than a relic of ecological decline. Protecting this species is not just about saving a bird but about maintaining the intricate web of life its beak symbolizes.

Instructively, studying the wood thrush’s beak offers a framework for analyzing avian adaptations in any context. Start by measuring beak dimensions and correlating them with diet and habitat. For example, a beak-to-head ratio can reveal degrees of specialization, while wear patterns may indicate feeding habits. Pairing field observations with laboratory analysis, such as stress testing beak materials, provides a comprehensive understanding of form and function. Whether for research or education, this approach transforms the beak from a mere anatomical feature into a window into evolutionary biology and ecology.

Vinyl vs. Wood Windows: Which Material Offers Longer Durability?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Thrush Species Beak Variations

The wood thrush, a bird celebrated for its ethereal song, does not possess a particularly long beak. Its beak is, in fact, relatively short and straight, adapted for foraging on the forest floor. This characteristic is typical of ground-feeding thrushes, which rely on quick, precise movements to capture insects and small invertebrates. However, beak variations among thrush species reveal fascinating adaptations to diverse diets and habitats.

Consider the contrast with the bluebird, a close relative of the wood thrush. Bluebirds have slightly longer, more slender beaks, better suited for catching flying insects mid-air. This difference highlights how beak morphology directly correlates with feeding behavior. For instance, species like the American robin, another thrush, exhibit broader, more robust beaks designed for consuming fruits and larger prey. These variations underscore the principle of evolutionary specialization, where beak shape becomes a key determinant of ecological niche.

To observe these differences firsthand, birdwatchers can employ a simple field technique: note the beak-to-head ratio. A wood thrush’s beak appears proportionally shorter compared to its skull, while a robin’s beak projects more prominently. Additionally, examining foraging behavior provides context—wood thrushes peck at leaf litter, whereas robins probe lawns with deeper, more forceful strikes. These observations not only enrich bird identification skills but also illustrate the functional significance of beak variations.

For those interested in deeper analysis, measuring beak length relative to body size offers quantitative insight. A study comparing thrush species found that wood thrush beaks average 1.2 cm in length, while robins’ beaks measure around 2.5 cm. This data reinforces the qualitative observations and suggests a clear adaptive divergence. Practical tip: use a field guide with detailed illustrations to compare beak shapes across species, enhancing both identification accuracy and appreciation for evolutionary biology.

In conclusion, while the wood thrush’s beak is not long, its design is a testament to the species’ ecological role. Thrush beak variations serve as a microcosm of evolutionary adaptation, where form follows function. By studying these differences, enthusiasts gain not only a deeper understanding of avian biology but also a framework for appreciating biodiversity in broader contexts. Whether through casual observation or rigorous measurement, exploring thrush beaks offers a tangible connection to the natural world’s intricate design.

Discovering the Lifespan of Wood Ducks: How Long Do They Live?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Beak Adaptation for Diet Needs

The wood thrush, a bird known for its ethereal song, does not possess a particularly long beak. Its beak is, in fact, relatively short and straight, adapted for its omnivorous diet. This seemingly simple characteristic is a testament to the intricate relationship between a bird's anatomy and its ecological niche.

Understanding Beak Morphology

Beak shape and size are not arbitrary; they are finely tuned tools shaped by evolutionary pressures. The wood thrush's beak, for instance, is designed for versatility. Its slight downward curve aids in plucking insects from foliage, while its sturdy structure allows it to crack open small fruits and seeds. This adaptability reflects the bird's diet, which consists of insects, earthworms, berries, and other small invertebrates.

Dietary Demands and Beak Specialization

Contrast the wood thrush with a hummingbird. Hummingbirds, with their long, slender beaks, are specialized nectar feeders. Their beak length allows them to reach deep into flowers, accessing nectar inaccessible to other birds. This specialization is a direct result of their reliance on nectar as a primary food source. Similarly, birds of prey like hawks and eagles have sharp, hooked beaks designed for tearing flesh, reflecting their carnivorous diet.

The Trade-Offs of Specialization

While specialization offers advantages, it also carries risks. A beak highly adapted for a specific food source can become a liability if that resource becomes scarce. The wood thrush's generalist beak, while less efficient at any one task, provides a broader range of feeding options, increasing its resilience in changing environments. This highlights the delicate balance between specialization and adaptability in the natural world.

Observing Beak Adaptations in Action

To appreciate beak adaptations, observe birds in their natural habitats. Notice how a woodpecker's chisel-like beak drills into wood, or how a finch's conical beak cracks open seeds. These observations provide tangible evidence of the profound connection between form and function in the avian world. By understanding these adaptations, we gain a deeper appreciation for the intricate ways in which birds are shaped by their environments and, in turn, shape them.

Polyurethane Drying Time: Factors Affecting Wood Finishing Process

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Measuring Wood Thrush Beak Size

The wood thrush, a bird celebrated for its ethereal song, often sparks curiosity about its physical attributes, particularly its beak. To address whether it has a long beak, precise measurement is key. Using calipers, researchers typically measure beak length from the tip to the base where it meets the skull, ensuring accuracy within 0.1 millimeters. This method, though straightforward, requires handling the bird gently to avoid stress, making it a task best suited for trained ornithologists or wildlife rehabilitators.

Comparative analysis reveals that the wood thrush’s beak averages between 15 and 18 millimeters in length, a size adapted for its omnivorous diet of insects, fruits, and small invertebrates. While not exceptionally long compared to birds like woodpeckers or toucans, its beak is proportionate to its body size, reflecting evolutionary specialization for foraging in forest floors. Measuring beak size across age groups—juveniles, subadults, and adults—can also highlight developmental changes, with adult beaks generally being slightly longer and more robust.

For enthusiasts or citizen scientists, measuring beak size in the field requires creativity. One practical approach is using a ruler and a clear photograph, aligning the ruler with the beak’s length in the image and adjusting for scale. However, this method is less precise and should be supplemented with observations of beak shape and curvature, which influence feeding behavior. For instance, a straighter beak might indicate a diet heavier in insects, while a slight curve could suggest more fruit consumption.

Caution must be exercised when interpreting beak size data. Environmental factors, such as habitat quality and food availability, can influence beak growth, leading to variations within populations. Additionally, handling wild birds without proper permits or training is unethical and often illegal. Instead, focus on non-invasive methods like observing feeding behavior or analyzing museum specimens, which provide valuable insights without disturbing live birds.

In conclusion, measuring wood thrush beak size offers a window into its ecology and adaptations. Whether through precise caliper measurements or field observations, understanding beak length contributes to broader knowledge of this species. By combining scientific rigor with ethical practices, enthusiasts can explore this question meaningfully, fostering appreciation for the wood thrush’s role in its ecosystem.

Durability of Wood Shingles: Lifespan and Maintenance Tips Revealed

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, a wood thrush does not have a long beak. Its beak is relatively short and straight, adapted for catching insects and eating fruits.

The wood thrush’s beak is similar in size and shape to other thrushes, such as the American robin, and is not notably longer or shorter.

The wood thrush’s beak is primarily used for foraging, allowing it to pick insects from the ground and consume berries and fruits.

No, the wood thrush is not typically confused with long-beaked birds. Its beak is distinctively short compared to birds like woodpeckers or shorebirds.

No, the beak of a wood thrush does not significantly change in size as the bird ages. Its shape and length remain consistent throughout its life.