In the old days, the length of a cord of wood was a standard measurement used to ensure fairness in firewood transactions. A cord of wood traditionally refers to a tightly stacked pile of firewood measuring 4 feet wide, 4 feet high, and 8 feet long, totaling 128 cubic feet. This measurement originated from the need for a consistent and reliable way to buy and sell firewood, especially during colder months when it was essential for heating. The term cord is believed to have derived from the use of a cord or string to measure the woodpile, ensuring it met the required dimensions. Understanding the historical context of a cord of wood highlights its importance in daily life and commerce before modern heating methods became widespread.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Measuring Methods: Traditional tools and techniques used to measure cordwood lengths accurately

- Standard Sizes: Historical definitions of a cord of wood and regional variations

- Stacking Practices: Old methods for stacking wood to ensure proper air circulation

- Seasoning Wood: Ancient techniques for drying wood to optimal moisture levels

- Transportation Tools: Early methods and tools used to move and deliver cordwood

Measuring Methods: Traditional tools and techniques used to measure cordwood lengths accurately

In the days before standardized measurements and laser tools, determining the length of a cord of wood was as much an art as it was a science. A cord, traditionally defined as a stack of wood 4 feet wide, 4 feet high, and 8 feet long, required precise measurement to ensure fair trade and efficient storage. Without modern conveniences, early woodcutters and traders relied on ingenuity, simple tools, and keen observation to achieve accuracy.

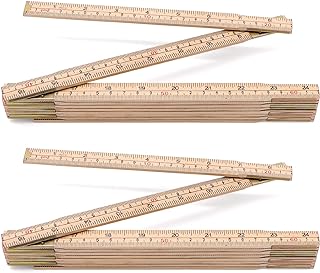

One of the most straightforward methods involved the use of a measuring rod, typically a wooden or metal pole marked with precise intervals. These rods were often custom-made, with clear notches or paint marks indicating feet and inches. To measure a cord, the rod would be laid along the length, width, and height of the stack, ensuring each dimension met the 4x4x8-foot standard. This method demanded a steady hand and a sharp eye, as even a slight misalignment could lead to errors. For added precision, some rods were paired with a level to confirm the ground was even, preventing skewed measurements.

Another technique leveraged the human body as a measuring tool. A woodcutter might use their own height, arm span, or stride length as a reference point. For instance, if a person’s arm span was 6 feet, they could estimate the 8-foot length by pacing out one and a third arm spans. While less precise than a measuring rod, this method was practical in remote areas where tools were scarce. It required practice and consistency, as individual variations in body measurements could introduce discrepancies.

For those with access to basic carpentry skills, a framing square became an invaluable tool. Originally designed for constructing right angles in building projects, the square could be adapted to measure linear distances. By laying the square along the edges of the woodpile and marking the endpoints, woodcutters could ensure straight lines and accurate dimensions. This method was particularly useful for verifying the width and height of the stack, as the square’s fixed 90-degree angle provided a reliable reference.

Finally, natural landmarks and existing structures often served as impromptu measuring aids. A fence post, the distance between two trees, or even the length of a wagon could be used to approximate the 8-foot length of a cord. While not as precise as dedicated tools, these methods were resourceful and widely accessible. They highlight the adaptability of early woodcutters, who turned their surroundings into practical measuring instruments.

In conclusion, measuring a cord of wood in the old days was a task that blended creativity with practicality. From custom-made rods to the human body, each method had its strengths and limitations. Together, these techniques ensured that even without modern tools, woodcutters could achieve the accuracy needed for fair trade and efficient storage. Their ingenuity remains a testament to the resourcefulness of those who worked with what they had.

Understanding the Lifespan of Wood Ticks: How Long Do They Live?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Standard Sizes: Historical definitions of a cord of wood and regional variations

The concept of a "cord" of wood, as a unit of measurement, has deep historical roots, but its definition has evolved and varied across regions. In the early days, when firewood was a primary source of heat, understanding the quantity of wood needed for the winter was crucial. A cord of wood was not just a random pile but a standardized measure, ensuring fairness in trade and adequate supply for households.

Historical Definitions:

In colonial America, a cord of wood was defined as a tightly stacked pile measuring 4 feet wide, 4 feet high, and 8 feet long, totaling 128 cubic feet. This definition emerged from practical necessity, as early settlers needed a reliable way to measure firewood for heating and cooking. The term "cord" itself is believed to originate from the use of a cord or string to measure the woodpile, ensuring it met the required dimensions. This standard was widely adopted because it provided a consistent volume, regardless of the size of the individual logs.

Regional Variations:

As settlers moved westward and communities developed independently, regional variations in the definition of a cord emerged. In some areas, particularly where wood was scarcer or more abundant, the dimensions were adjusted to suit local needs. For example, in parts of New England, a "face cord" became a common term, referring to a stack of wood 4 feet high and 8 feet long but only as deep as the length of the logs, typically 16 inches. This variation allowed for easier stacking and transportation but reduced the overall volume to about one-third of a full cord. In contrast, some Midwestern states adopted a "running cord," which was measured by the length of the woodpile rather than its volume, leading to inconsistencies in the amount of wood received.

Practical Implications:

These regional variations highlight the importance of clarity in measurement, especially in trade. For instance, a buyer in New England purchasing a "cord" of wood might receive significantly less than someone in the Midwest, even if the term was the same. To avoid disputes, many states began to legislate the definition of a cord, often reverting to the original 128 cubic feet standard. Today, most regions adhere to this definition, but historical variations still influence local terminology and practices.

Modern Takeaway:

Understanding the historical and regional definitions of a cord of wood is not just a lesson in history but a practical guide for modern consumers. When purchasing firewood, always confirm the measurement standards used by the seller. Ask whether they are selling a full cord, face cord, or another variation. Knowing these differences ensures you receive the amount of wood you need and pay a fair price. Additionally, for those cutting their own wood, adhering to the standard 4x4x8 dimensions guarantees a consistent supply for the winter months, just as it did for early settlers.

By recognizing these historical and regional nuances, you can navigate the world of firewood with confidence, ensuring warmth and fairness in every transaction.

Treated Wood Lifespan: Factors Affecting Durability and Longevity Explained

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Stacking Practices: Old methods for stacking wood to ensure proper air circulation

In the old days, stacking wood wasn’t just about piling logs—it was a craft that balanced stability, accessibility, and air circulation to ensure the wood dried properly. A cord of wood, traditionally measured as 128 cubic feet (4 feet high by 4 feet deep by 8 feet long), required careful arrangement to avoid rot and pests. Airflow was critical, as stagnant moisture could render the wood unusable. Early stackers understood that a well-ventilated pile not only preserved the wood but also accelerated seasoning, making it ready for winter fires.

One of the most effective old methods was the *crisscross technique*, where logs were stacked in alternating layers to create natural air pockets. This method mimicked the stability of a brick wall while allowing air to flow through the gaps. For example, the first layer would run east-west, the second north-south, and so on. This pattern prevented the stack from shifting and promoted even drying. Farmers often paired this with a *base layer of branches* or *pallets* to elevate the wood off the ground, reducing moisture absorption from the soil.

Another traditional practice was the *round stack*, a circular arrangement often used in Europe. Logs were leaned against a central pole or against each other in a cone shape, with the thickest ends at the bottom. This method not only saved space but also allowed air to circulate freely around the entire structure. While less common today, it remains a testament to the ingenuity of old-world wood stacking. A key caution: avoid packing the wood too tightly, as this restricts airflow and traps moisture.

For those with limited space, the *single-row stack* was a practical solution. Logs were placed in a straight line, either horizontally or vertically, with gaps between each piece. This method was simple but required a level surface to prevent rolling. To enhance airflow, stackers often left the top layer slightly loose or added a *roof of bark or tarps* to protect the wood from rain while still allowing ventilation. This approach was particularly useful for smaller quantities, such as a face cord (one-third of a full cord).

The takeaway from these old methods is clear: proper stacking isn’t just about quantity—it’s about quality. Whether using the crisscross technique, round stack, or single-row method, the goal is to maximize airflow while maintaining stability. Modern stackers can learn from these practices by prioritizing ventilation and elevation, ensuring their wood remains dry and ready for use. After all, a well-stacked cord isn’t just a pile of logs—it’s a testament to patience and practicality.

Family Dollar Long Wood Narrow Sticks: Uses, Benefits, and Creative Ideas

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Seasoning Wood: Ancient techniques for drying wood to optimal moisture levels

In ancient times, the process of seasoning wood was as much an art as it was a science, honed over generations to ensure firewood burned efficiently and lasted through harsh winters. A cord of wood, measuring 4 feet by 4 feet by 8 feet, was the standard unit for stacking and seasoning, but the time required to dry it varied widely depending on climate, wood type, and technique. For instance, hardwoods like oak or hickory could take 6 to 12 months to season properly, while softer woods like pine dried in half that time. The key was patience, as rushing the process often led to smoky, inefficient fires.

One ancient technique involved stacking wood in open-air cribs, allowing air to circulate freely around the logs. These cribs were often built off the ground using stones or wooden pallets to prevent moisture absorption from the soil. The wood was split into logs no thicker than 4 inches, as thinner pieces dried faster and more evenly. In regions with high humidity, such as coastal areas, wood was sometimes covered with a single layer of thatch or straw to shield it from rain while still permitting airflow. This method required minimal tools but demanded careful monitoring to avoid rot or insect infestation.

Another approach, favored in colder climates, was to season wood indoors in a barn or shed. Here, the wood was stacked tightly against a wall, with spacers between layers to promote air circulation. The controlled environment reduced the risk of mold and allowed for year-round drying. However, this method required ample storage space and was often reserved for smaller quantities of wood. Ancient texts and folklore suggest that wood seasoned in this manner was prized for its consistent quality, making it ideal for prolonged use in hearths or blacksmith forges.

Comparatively, some cultures employed a more labor-intensive technique known as "air-drying in the round." Instead of splitting logs immediately, they were left whole and stacked vertically, allowing the ends to dry first and gradually draw moisture from the center. This method, though slower, preserved the wood’s structural integrity and was particularly useful for crafting tools or furniture. It highlights the ancient understanding of wood’s natural properties and the importance of working with, rather than against, its inherent characteristics.

The takeaway from these techniques is that seasoning wood was a deliberate, thoughtful process rooted in observation and adaptation. Modern woodworkers and homesteaders can still benefit from these methods, especially when resources are limited. For example, splitting wood into smaller pieces and using cribs remains one of the most effective ways to season a cord of wood naturally. By studying these ancient practices, we not only honor the ingenuity of our ancestors but also gain practical insights into sustainable living.

Wood Pellets Lifespan: How Long Do They Last and Stay Effective?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Transportation Tools: Early methods and tools used to move and deliver cordwood

In the days before mechanized transport, moving cordwood was a labor-intensive task that required ingenuity, strength, and the right tools. A cord of wood, measuring 4 feet high, 4 feet wide, and 8 feet long, weighed upwards of 2 tons, making its transportation a significant challenge. Early methods relied on human and animal power, supplemented by simple yet effective tools designed to maximize efficiency and minimize effort.

One of the most common tools for moving cordwood was the sled, particularly in snowy regions. Sleds, often made of wood with runners, were pulled by horses or oxen. The sled’s low friction on snow allowed for easier movement of heavy loads. To prevent the wood from shifting, workers would secure the cord with ropes or chains. This method was especially useful in rural areas where roads were unpaved and winter provided a natural advantage. However, sleds were impractical in warmer climates or during seasons without snow, necessitating alternative solutions.

In areas without snow, the use of wagons became essential. Wagons with high sides and sturdy wheels were pulled by draft animals, typically horses or oxen. The key to successful cordwood transport by wagon was proper loading. Workers would stack the wood tightly, ensuring it was balanced to avoid tipping. A well-packed cord could reduce the risk of shifting during transit. For longer distances, teams of animals were often used to share the load, and drivers would take frequent breaks to rest the animals and check the cargo.

Another innovative tool was the use of log tongs, which allowed workers to lift and move individual pieces of wood with precision. These tongs, made of metal or wood, were designed to grip logs securely, reducing the risk of injury and increasing efficiency. When combined with a team of workers, log tongs could be used to load and unload cordwood quickly, even in tight spaces. This method was particularly useful for short-distance transport, such as moving wood from a cutting site to a nearby storage area.

For water-adjacent regions, waterways provided a natural transportation route. Cordwood was often floated down rivers or canals using rafts or barges. This method required careful planning, as the wood had to be securely tied to prevent it from drifting away. Floating cordwood was a cost-effective solution for long-distance transport, especially in regions with extensive river systems. However, it was dependent on water levels and seasonal conditions, limiting its reliability.

In conclusion, early methods of transporting cordwood were shaped by the available resources and environmental conditions. From sleds and wagons to log tongs and water transport, each tool and technique was designed to overcome the challenges of moving heavy loads. These methods, though labor-intensive, laid the foundation for modern transportation practices and highlight the resourcefulness of those who relied on cordwood for fuel and livelihood.

Ground Contact Wood Durability: Lifespan and Preservation Tips Explained

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

A cord of wood has historically been defined as a stack of wood measuring 4 feet wide, 4 feet high, and 8 feet long, totaling 128 cubic feet. This definition has remained consistent for centuries.

While the standard cord measurement was widely accepted, some regions or individuals might have used informal or slightly different measurements. However, the 128 cubic feet definition was the most common and standardized.

In the past, a cord of wood was often stacked by hand in a neat, compact pile to ensure it met the 4x4x8 dimensions. Tools like axes and measuring sticks were used to ensure accuracy.

While a cord was the most common measurement, smaller quantities like a "face cord" (a stack 4 feet high and 8 feet long but varying in width) or a "rick" were also used, depending on local customs and needs.

![EBISU Basic Level 600mm [Silver] ED-60N (Japan Import)](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/61YhyDhXU1L._AC_UL320_.jpg)