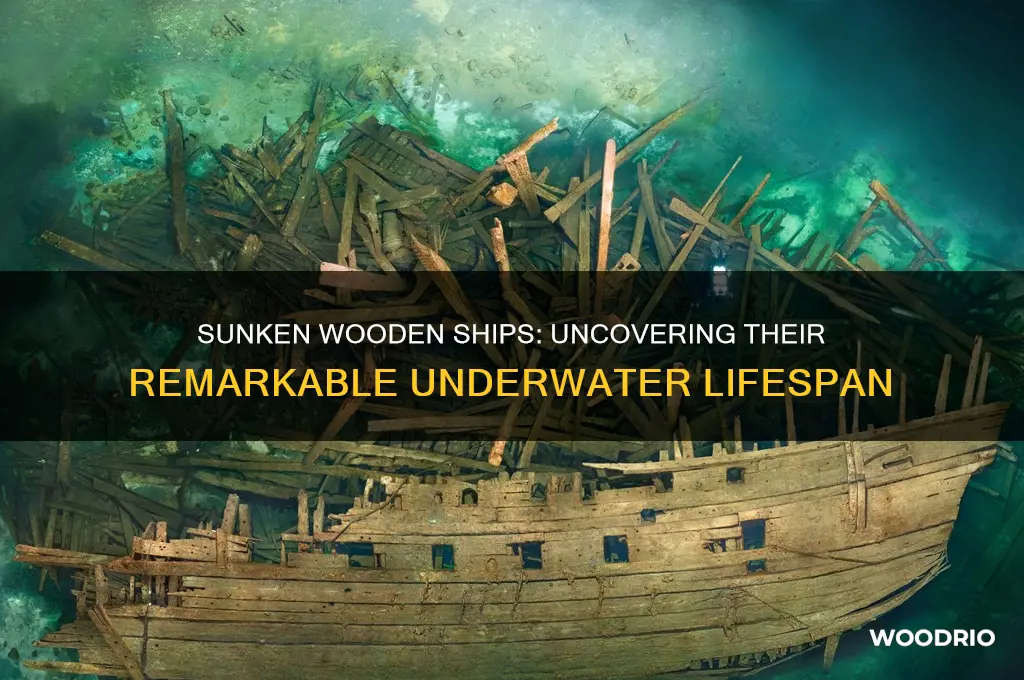

The longevity of sunken wooden ships is a fascinating subject that intertwines maritime history, marine biology, and environmental science. When a wooden vessel sinks, its fate is largely determined by the surrounding conditions, such as water depth, salinity, temperature, and the presence of shipworms or other wood-boring organisms. In cold, deep, or anoxic waters, where oxygen and wood-degrading organisms are scarce, wooden ships can remarkably endure for centuries, preserving their structures and artifacts. Conversely, in warmer, shallow, or oxygen-rich environments, rapid decay occurs due to biological activity and chemical erosion. Notable examples, like the Vasa in Sweden or ancient shipwrecks in the Mediterranean, highlight how sunken wooden ships can last anywhere from a few decades to millennia, offering invaluable insights into the past while underscoring the delicate balance between preservation and degradation in underwater environments.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Factors affecting ship decay

Sunken wooden ships, once symbols of maritime prowess, face a relentless battle against the elements beneath the waves. Their longevity underwater is not a fixed timeline but a complex interplay of factors that dictate their decay. Understanding these factors is crucial for archaeologists, historians, and marine enthusiasts alike, as they strive to preserve these submerged relics.

The Role of Water Chemistry: A Delicate Balance

Water chemistry plays a pivotal role in determining how quickly a wooden ship deteriorates. In acidic waters, such as those found in certain coastal areas or polluted environments, the pH levels accelerate the breakdown of cellulose in wood, causing it to become brittle and disintegrate faster. Conversely, alkaline waters can slow decay but may promote the growth of organisms that bore into the wood. For instance, the Vasa, a 17th-century Swedish warship, survived centuries in the brackish, low-oxygen waters of Stockholm’s harbor, which inhibited microbial activity. To mitigate decay, archaeologists often monitor pH levels and consider treatments like desalinization or controlled reburial in sediment to stabilize artifacts.

Biological Predators: The Silent Destroyers

Wooden ships are prime targets for marine organisms that feed on or inhabit wood. Shipworms, a type of marine bivalve, secrete enzymes that dissolve cellulose, leaving behind honeycomb-like tunnels that weaken the ship’s structure. Barnacles, algae, and fungi also contribute to decay by trapping moisture or physically degrading the surface. In tropical waters, where these organisms thrive, a wooden ship can be reduced to rubble in as little as 10–20 years. Cold, deep waters, however, slow biological activity, preserving ships for centuries. For preservation efforts, removing organisms and applying anti-fouling treatments can extend a ship’s underwater lifespan.

Physical Forces: The Unseen Hands of Destruction

The physical environment exerts constant pressure on sunken ships. Strong currents and wave action can scatter debris, while shifting sediments bury or expose parts of the ship, altering decay rates. For example, the Mary Rose, Henry VIII’s flagship, was preserved in the silty seabed of the Solent, where anaerobic conditions slowed decay. In contrast, ships in exposed areas may collapse under their own weight or be crushed by moving debris. To protect vulnerable sites, archaeologists use techniques like sandbagging or creating artificial reefs to buffer against physical forces.

Human Intervention: A Double-Edged Sword

Human activity can either hasten or halt a ship’s decay. Salvage operations, fishing nets, and anchors often damage fragile structures, while pollution introduces chemicals that accelerate deterioration. On the flip side, deliberate conservation efforts, such as controlled excavation and the use of preservatives like polyethylene glycol (PEG), can stabilize wood and prevent shrinkage. The Bremen Cog, a medieval trading vessel, was successfully preserved through PEG treatment after its discovery in the Weser River. Balancing the need for exploration with preservation is essential to ensuring these historical treasures endure.

Climate Change: The Emerging Threat

Rising sea temperatures and ocean acidification pose new challenges for sunken wooden ships. Warmer waters increase biological activity, while acidification weakens wood fibers, making ships more susceptible to decay. For instance, shipwrecks in the Baltic Sea, once protected by cold, low-oxygen conditions, now face accelerated deterioration as temperatures rise. Proactive measures, such as monitoring environmental changes and developing adaptive conservation strategies, are critical to safeguarding these underwater heritage sites for future generations.

By addressing these factors—water chemistry, biological activity, physical forces, human intervention, and climate change—we can better predict and manage the decay of sunken wooden ships, ensuring their stories remain intact beneath the waves.

How Long Does Bow Wood Last Before Losing Quality?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Role of water depth in preservation

The depth at which a wooden shipwreck rests underwater significantly influences its preservation. In shallow waters, where sunlight penetrates and oxygen levels are higher, marine organisms like shipworms and bacteria thrive, accelerating the degradation of wood. These organisms, coupled with wave action and sediment abrasion, can reduce a wooden ship to splinters within decades. For instance, the *Mary Rose*, Henry VIII’s flagship, lay in shallow waters for centuries and suffered extensive damage from biological and physical forces before its recovery.

Contrastingly, deeper waters act as a natural preservative. Below the photic zone (typically 200–300 meters), sunlight diminishes, and temperatures drop, slowing biological activity. Anaerobic conditions (lack of oxygen) in these depths inhibit wood-boring organisms and bacteria, effectively pickling the wood. The *Vasa*, a 17th-century Swedish warship, sank in Stockholm’s harbor and was preserved remarkably well due to the cold, low-oxygen environment. Similarly, ancient shipwrecks in the Black Sea’s anoxic depths have been found with intact wooden structures, some over 2,400 years old.

However, depth alone isn’t the sole determinant of preservation. Sedimentation plays a critical role. In deeper waters, fine sediments can bury a shipwreck, shielding it from currents and scavengers. This burial creates a stable, low-energy environment that further slows decay. For example, the *Antikythera Shipwreck*, discovered at 60 meters deep, was preserved under layers of sand, protecting its wooden remnants and artifacts. Yet, in areas with strong currents or turbid waters, even deep-water wrecks can be exposed and eroded over time.

For those seeking to preserve sunken wooden ships, understanding these depth-related factors is crucial. Shallow-water wrecks require immediate intervention, such as encapsulation or relocation, to halt rapid deterioration. Deeper sites, while naturally protective, still face threats from trawling, looting, and environmental changes. Conservation efforts should prioritize in situ preservation for deep-water wrecks, using techniques like sediment stabilization or protective barriers. For shallow sites, recovery and controlled conservation in laboratory settings may be the only viable option.

In summary, water depth acts as a double-edged sword in the preservation of sunken wooden ships. While shallow waters hasten decay through biological and physical forces, deeper environments offer natural protection through cold temperatures, low oxygen, and sediment burial. By leveraging these insights, archaeologists and conservators can tailor strategies to safeguard these fragile pieces of maritime history for future generations.

Composite vs. Wood Fences: Which Lasts Longer in Your Yard?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Impact of marine organisms on wood

Marine organisms play a pivotal role in the degradation of sunken wooden ships, often determining how long these structures endure beneath the waves. From microscopic bacteria to larger invertebrates, these organisms exploit wood as both a habitat and a food source, accelerating its decomposition. For instance, shipworms, a type of marine bivalve, bore into wood, digesting its cellulose and leaving behind a honeycomb of tunnels that weaken the material. Similarly, fungi and bacteria break down lignin and cellulose, the primary components of wood, through enzymatic processes. This biological assault can reduce a wooden ship’s structural integrity within decades, depending on the species present and environmental conditions.

To mitigate the impact of marine organisms, preservation strategies must focus on creating an inhospitable environment for them. One effective method is the application of protective coatings, such as copper sheathing or modern antifouling paints, which deter wood-boring organisms. Historical ships like the *Mary Rose* employed lead sheathing, though modern alternatives are more durable and environmentally friendly. Additionally, treating wood with preservatives like creosote or copper azole can inhibit microbial activity, extending the lifespan of submerged structures. However, these treatments must be reapplied periodically, as they degrade over time, especially in saltwater environments.

A comparative analysis of sunken ships reveals that those in colder, low-oxygen environments, such as the Baltic Sea or deep ocean trenches, often survive longer due to reduced biological activity. For example, the *Vasa*, a 17th-century Swedish warship, remained remarkably intact for centuries in the Baltic’s cold, brackish waters, where wood-boring organisms are less prevalent. In contrast, ships in tropical or temperate waters, like those in the Caribbean, degrade rapidly due to higher temperatures and a greater diversity of marine life. This highlights the importance of location in determining a ship’s longevity, with environmental factors often outweighing preservation efforts.

Practical tips for archaeologists and conservationists include monitoring water chemistry and biological activity around sunken ships. Regular inspections can identify early signs of infestation, allowing for timely intervention. For instance, installing barriers like geotextile fabrics can limit access by wood-boring organisms, while controlled sedimentation can bury and protect exposed wood. In some cases, relocating artifacts to controlled environments, such as conservation laboratories, may be necessary to halt degradation. By understanding the specific threats posed by marine organisms, stakeholders can implement targeted strategies to preserve these invaluable historical artifacts for future generations.

Yellowjackets' Survival Timeline: How Long Do They Thrive in the Woods?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Wood type and durability underwater

The longevity of sunken wooden ships underwater is significantly influenced by the type of wood used in their construction. Hardwoods like oak, teak, and chestnut have proven to withstand the test of time, with some shipwrecks remaining remarkably intact for centuries. Oak, in particular, is renowned for its natural resistance to decay due to its high tannin content, which acts as a preservative. For instance, the Mary Rose, an English warship that sank in 1545, was primarily constructed from oak and was recovered in 1982 with much of its structure still preserved. This highlights the critical role of wood selection in determining a ship’s underwater durability.

Not all woods fare equally well beneath the waves. Softwoods, such as pine and fir, are more susceptible to degradation due to their lower density and lack of natural preservatives. These woods often decompose within decades, unless treated with modern preservatives or protected by specific environmental conditions. For example, shipwrecks in cold, low-oxygen environments, like the Baltic Sea, can preserve even softwoods for extended periods. However, in warmer, oxygen-rich waters, softwoods typically deteriorate rapidly, leaving behind only metal fasteners and artifacts.

Environmental factors interact with wood type to dictate durability. Anaerobic conditions, such as those found in deep, sediment-covered waters, slow decay by limiting the activity of wood-eating organisms like shipworms and fungi. In contrast, shallow, warm waters with high oxygen levels accelerate decomposition. For instance, teak, prized for its natural oils and density, thrives in tropical waters but may still succumb to shipworms if exposed to oxygenated environments. Understanding these interactions is crucial for predicting how long a wooden ship will last underwater.

Practical considerations for modern underwater wood preservation include selecting naturally durable woods and applying protective treatments. Epoxy resins and polyethylene glycol (PEG) are commonly used to stabilize waterlogged wood, preventing it from crumbling upon exposure to air. For hobbyists or historians working with small-scale wooden artifacts, soaking in a 50% PEG solution for 6–12 months can effectively replace water in the wood cells, ensuring structural integrity. Combining traditional wood choices with modern conservation techniques maximizes the lifespan of wooden structures underwater, whether for historical preservation or contemporary marine projects.

Mastering Wood Bending: Techniques, Time, and Tips for Perfect Curves

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Preservation techniques for sunken ships

Sunken wooden ships, when submerged in the right conditions, can endure for centuries. The key to their longevity lies in the preservation techniques applied, both naturally and through human intervention. Cold, low-oxygen environments, such as deep-sea or freshwater sites, slow the decay of wood by inhibiting microbial activity. However, when these conditions are not met, or when ships are exposed to saltwater, marine organisms, and shifting sediments, preservation becomes a challenge. To combat these threats, archaeologists and conservationists employ a range of techniques to ensure these maritime relics survive for future study and appreciation.

One of the most effective methods for preserving sunken wooden ships is in situ preservation, which involves leaving the ship in its original location while protecting it from further deterioration. This approach often includes the installation of protective structures, such as sediment blankets or geotextile covers, to shield the wreck from sediment erosion and biological damage. For instance, the Vasa, a 17th-century Swedish warship, was preserved in situ before being raised, with divers carefully removing sediment and applying preservatives to stabilize the wood. In cases where in situ preservation is not feasible, controlled excavation and relocation may be necessary. This process requires meticulous planning to avoid structural damage during recovery and transport.

Once a ship is recovered, conservation treatments become critical to halting decay. One common technique is impregnation with polyethylene glycol (PEG), a water-soluble polymer that replaces the water in the wood cells, preventing shrinkage and cracking as the wood dries. The treatment typically involves submerging the wood in a bath of PEG solution with increasing concentrations (e.g., from 30% to 60% over several months) to ensure thorough penetration. Another method is freeze-drying, which removes water from the wood by freezing it and then reducing the surrounding pressure, allowing the ice to sublimate directly into vapor. This process preserves the wood’s structure without the risk of distortion.

Preventing biological degradation is equally important, especially for ships exposed to saltwater. Desalination is often the first step, involving the gradual removal of salts from the wood through repeated soaking in freshwater. Failure to desalinate can lead to crystallization of salts as the wood dries, causing internal damage. Additionally, fungicidal treatments may be applied to protect against mold and fungi. Copper-based solutions, such as copper sulfate, are commonly used for this purpose, though their application must be carefully monitored to avoid staining or weakening the wood.

Finally, environmental control plays a vital role in long-term preservation. Wooden artifacts must be stored in climate-controlled environments to prevent fluctuations in temperature and humidity, which can accelerate decay. Museums often maintain relative humidity levels between 45% and 55% and temperatures around 20°C (68°F) to ensure stability. Regular monitoring for pests and mold is also essential, as even small infestations can cause significant damage over time. By combining these techniques, conservationists can extend the lifespan of sunken wooden ships, preserving them as invaluable windows into maritime history.

Durability of Permanent Wood Foundations: Lifespan and Longevity Explained

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Sunken wooden ships can last for centuries underwater, often preserved by cold temperatures, low oxygen levels, and sediment burial. In ideal conditions, such as in deep, cold waters or anaerobic environments, they can survive for over 1,000 years.

The longevity of sunken wooden ships depends on factors like water temperature, salinity, depth, oxygen levels, and biological activity. Warmer, oxygen-rich waters accelerate decay, while colder, deeper waters with sediment cover can preserve wood for much longer.

Yes, sunken wooden ships can be preserved after recovery through a process called conservation. This involves treating the wood with chemicals like polyethylene glycol (PEG) to replace water and stabilize the structure, preventing it from crumbling upon exposure to air.