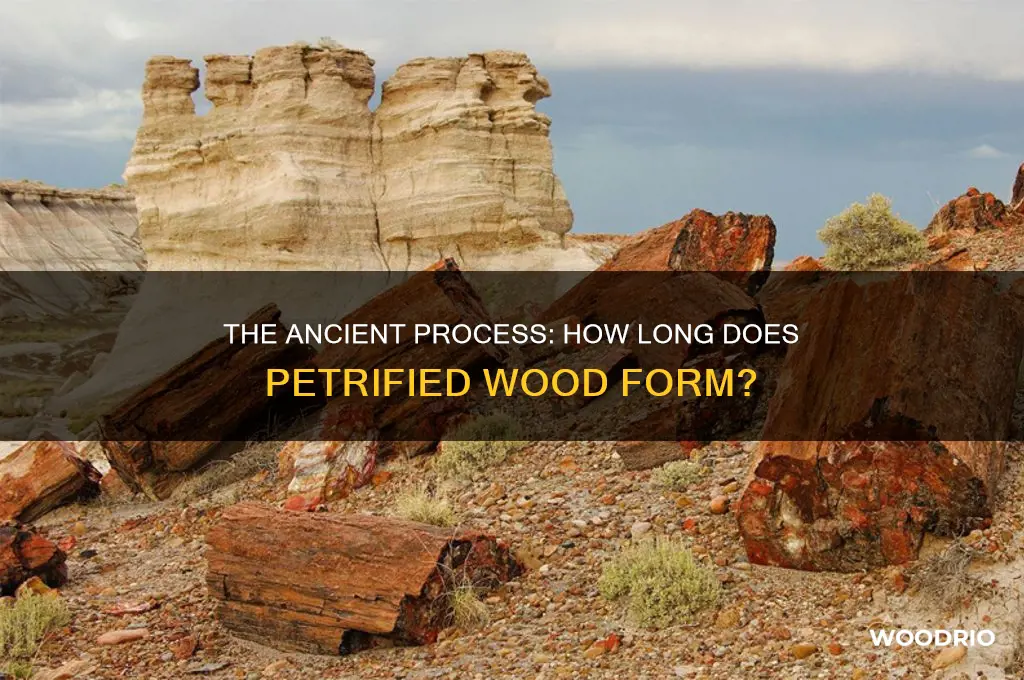

Petrified wood, a fascinating natural wonder, is the result of a slow and intricate process that transforms ancient trees into stone over millions of years. This remarkable phenomenon begins when a tree is buried under sediment, such as volcanic ash, mud, or sand, cutting off oxygen and preventing decay. Over time, groundwater rich in minerals like silica seeps into the wood, gradually replacing the organic material with minerals cell by cell. This process, known as permineralization, can take anywhere from 5,000 to 50 million years, depending on environmental conditions such as the mineral content of the water, temperature, and pressure. The end result is a fossilized log that retains the original structure of the wood, often with stunningly preserved details like tree rings and even cellular patterns, all transformed into a durable, stone-like material.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Formation Time | Typically takes millions of years (25 to 200+ million years) |

| Process | Fossilization through permineralization (minerals replace organic material) |

| Key Conditions | - Burial under sediment - Presence of mineral-rich water - Lack of oxygen |

| Minerals Involved | Primarily silica (quartz), but also calcite, pyrite, and others |

| Tree Type | Commonly conifers and other ancient tree species |

| Preservation Level | Cellular structure often preserved in detail |

| Environmental Setting | Often forms in floodplains, volcanic ash deposits, or river systems |

| Notable Locations | Petrified Forest National Park (USA), Argentina, China, and others |

| Hardness (Mohs Scale) | 7 (similar to quartz) |

| Color Variation | Depends on minerals present (e.g., red from iron, green from chromium) |

| Rarity | Relatively rare due to specific conditions required |

Explore related products

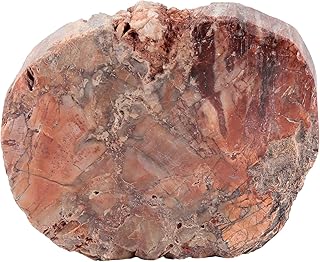

$64.57 $77.99

What You'll Learn

- Mineralization Process: Silica-rich water seeps into wood, replacing organic material with minerals like quartz

- Environmental Conditions: Formation requires burial in sediment with high mineral content and low oxygen

- Timeframe Variations: Petrification can take thousands to millions of years, depending on conditions

- Preservation Factors: Rapid burial and stable environments enhance wood preservation and petrification

- Fossilization Stages: Includes permeation, permineralization, and complete replacement of wood structure

Mineralization Process: Silica-rich water seeps into wood, replacing organic material with minerals like quartz

The transformation of ancient wood into stone is a captivating geological process, and at its heart lies the mineralization process, a delicate dance of silica-rich water and organic matter. This natural phenomenon, though slow, is a testament to the Earth's ability to preserve history in the most unexpected ways.

A Subtle Invasion: Silica's Journey into Wood

Imagine a tree, long fallen, buried beneath layers of sediment. Over time, groundwater, rich in silica, begins its silent invasion. This water, often acidic, carries dissolved minerals, primarily silica (SiO2), which is the key player in the petrification process. As the water seeps through the wood's cellular structure, it initiates a gradual replacement of the organic material. This is not a rapid takeover but a meticulous, cell-by-cell substitution, where silica deposits fill the voids left by decaying plant matter. The result is a replica of the original wood, but now, it's a mineralized version, with quartz being the most common mineral formed.

Time's Role in Petrification

The duration of this process is a subject of fascination. It is not a quick event but a geological journey spanning millennia. Scientists estimate that petrified wood formation can take anywhere from a few thousand to several million years. The variability depends on numerous factors, including the silica concentration in the water, temperature, and the wood's original structure. For instance, a study on the famous Petrified Forest in Arizona revealed that the process there took approximately 60,000 years, with silica-rich volcanic ash playing a significant role in the rapid preservation of the wood.

A Delicate Balance: Conditions for Mineralization

Creating petrified wood requires a specific set of conditions. Firstly, the wood must be buried quickly, preventing complete decay and providing an anoxic environment. This burial allows for the preservation of the wood's cellular structure, which is crucial for the silica to infiltrate and replicate. Secondly, the presence of silica-rich water is essential. This water can come from various sources, such as volcanic activity, which provides a rich supply of silica, or groundwater flowing through silica-bearing rocks. The pH of this water is critical; slightly acidic conditions enhance silica solubility, facilitating its movement into the wood.

Practical Insights for Enthusiasts

For those intrigued by the idea of witnessing this process, it's essential to understand that petrification is a rare occurrence. However, certain environments are more conducive to finding petrified wood. Volcanic regions, for instance, offer a higher chance due to the abundance of silica-rich ash. Additionally, areas with ancient riverbeds or floodplains, where wood could be quickly buried, are prime locations. When identifying petrified wood, look for the characteristic quartz-like appearance, often with vibrant colors, a result of various impurities and minerals present during formation.

In the realm of geology, the mineralization process is a captivating narrative of transformation, where silica-rich water becomes the artist, painting over organic matter with mineral strokes, creating a timeless masterpiece—petrified wood. This process, though slow, offers a unique glimpse into Earth's history, preserving ancient life in stone.

Citristrip on Wood: Optimal Time for Effective Paint Removal

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Environmental Conditions: Formation requires burial in sediment with high mineral content and low oxygen

The transformation of wood into stone, a process known as petrification, is a geological marvel that hinges on specific environmental conditions. Among these, burial in sediment with high mineral content and low oxygen levels is paramount. This unique combination creates an environment where organic matter is preserved and gradually replaced by minerals, rather than being decomposed by microorganisms. Without these conditions, wood would simply rot away, leaving no trace of its existence.

Consider the steps required to replicate this process artificially. To petrify wood in a controlled setting, one would need to submerge the wood in a solution rich in minerals like silica, calcium, or iron, while ensuring the environment is devoid of oxygen. This can be achieved by sealing the wood in an airtight container filled with mineral-rich water. Over time—often years or even decades—the minerals permeate the wood’s cellular structure, replacing organic material with crystalline deposits. This method, while time-consuming, underscores the importance of high mineral content and low oxygen in natural petrification.

In nature, these conditions are often found in riverbeds, floodplains, or volcanic ash deposits. For instance, the Petrified Forest National Park in Arizona owes its existence to ancient trees buried under volcanic ash and mud, rich in silica from groundwater. Over millions of years, the silica crystallized into quartz, preserving the wood’s intricate details. This example highlights how specific geological settings—such as areas with frequent volcanic activity or mineral-laden water sources—are ideal for petrification.

However, achieving the right balance of mineral content and oxygen deprivation is not without challenges. Too much oxygen can lead to decay, while insufficient mineral availability slows or halts the petrification process. Practical tips for enthusiasts include selecting wood with a high cellulose content, as it provides a better framework for mineral infiltration, and ensuring the burial site is protected from oxygen exposure. For those studying petrified wood, analyzing sediment composition can reveal clues about the ancient environment in which the wood was preserved.

In conclusion, the environmental conditions required for petrification are both precise and fascinating. Burial in sediment with high mineral content and low oxygen is not merely a detail but a critical factor that determines whether wood becomes a lasting geological record or fades into obscurity. Understanding these conditions not only deepens our appreciation for natural wonders like petrified forests but also offers insights into Earth’s ancient ecosystems.

Durability of Wooden Homes: Lifespan and Longevity Explained

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Timeframe Variations: Petrification can take thousands to millions of years, depending on conditions

Petrified wood formation is a geological process that hinges on the interplay of mineral-rich water, organic matter, and time. Under ideal conditions—such as consistent groundwater flow saturated with silica and a stable, buried environment—petrification can occur within thousands of years. For instance, the renowned Petrified Forest National Park in Arizona showcases logs that transformed into quartz-rich stone over approximately 225 million years, but the actual mineralization process likely took a fraction of that time, estimated at 5,000 to 50,000 years. This highlights how localized conditions can accelerate the process.

However, when conditions are less optimal, petrification stretches into the millions of years. Slow mineral infiltration, intermittent water availability, or unstable burial environments can prolong the transformation. In regions like Argentina’s Patagonia, petrified wood specimens have been dated to over 150 million years old, with mineralization occurring gradually over millions of years due to sporadic groundwater activity. This contrast underscores how environmental factors dictate the timeline, making petrification a highly variable process.

To illustrate the extremes, consider two scenarios: rapid petrification in hydrothermal environments versus slow transformation in arid climates. In hydrothermal settings, such as those near volcanic activity, silica-rich fluids can permeate wood at elevated temperatures, reducing the timeframe to mere millennia. Conversely, in dry regions where groundwater is scarce, petrification may crawl along for tens of millions of years. These examples demonstrate how geological context acts as a throttle on the process.

Practical implications arise for collectors and geologists alike. When assessing petrified wood, the degree of mineralization and crystal clarity can hint at the duration of formation. Highly detailed, gem-like specimens often indicate faster processes, while coarser, less uniform structures suggest prolonged exposure. For enthusiasts, understanding these variations can deepen appreciation for the unique conditions that created each piece.

In summary, petrification’s timeframe is not fixed but a spectrum shaped by environmental factors. From thousands to millions of years, the process adapts to its surroundings, leaving behind a record of Earth’s history in stone. Recognizing these variations not only enriches scientific understanding but also enhances the allure of petrified wood as a natural wonder.

How Long Will a 40lb Bag of Wood Pellets Last?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$6.99

Preservation Factors: Rapid burial and stable environments enhance wood preservation and petrification

Rapid burial is a critical factor in the preservation of wood and its subsequent petrification. When wood is quickly buried under sediment, it is shielded from oxygen and destructive organisms that would otherwise accelerate decay. This anaerobic environment slows the breakdown process, giving minerals more time to infiltrate the wood’s cellular structure. For instance, in environments like river deltas or volcanic ash deposits, wood can be buried within days or weeks, significantly increasing its chances of preservation. Without this rapid burial, wood is often reduced to coal or completely decomposed, leaving no trace for petrification to occur.

Stable environments play an equally vital role in the petrification process. Fluctuations in temperature, pH, or mineral availability can disrupt the slow, steady replacement of organic material with minerals like silica or calcite. Ideal conditions include areas with consistent groundwater flow rich in dissolved minerals, such as ancient floodplains or shallow marine basins. For example, the petrified forests of Arizona formed over millions of years in a stable, arid climate where groundwater carried silica from volcanic ash into buried logs. In contrast, unstable environments, such as those prone to erosion or frequent flooding, often fail to preserve wood long enough for petrification to complete.

To understand the interplay of these factors, consider the steps required for successful petrification. First, rapid burial isolates the wood from oxygen and organisms. Second, a stable environment ensures that mineral-rich water can permeate the wood over extended periods, often thousands to millions of years. Third, the absence of physical disturbances allows the minerals to crystallize within the wood’s cellular structure, transforming it into stone. Practical tips for identifying potential petrification sites include looking for areas with historical volcanic activity, ancient riverbeds, or stable sedimentary layers, as these are more likely to meet the necessary conditions.

Comparing petrified wood from different environments highlights the importance of preservation factors. Wood buried in volcanic ash, like that found in Yellowstone, often petrifies faster due to the high silica content and rapid burial. In contrast, wood in swampy environments may take longer to petrify, as the acidic conditions can dissolve minerals before they crystallize. This comparison underscores why rapid burial and stable environments are not just beneficial but essential for the formation of petrified wood. Without them, the delicate balance required for this natural process is easily disrupted.

Finally, the takeaway is clear: preservation factors are the linchpin of petrification. Rapid burial acts as the initial safeguard, while stable environments sustain the process over millennia. For enthusiasts or researchers, focusing on these factors can guide the discovery of new petrified wood sites. By understanding the conditions that enhance preservation, we not only appreciate the rarity of petrified wood but also gain insights into Earth’s geological history. This knowledge transforms petrified wood from a mere curiosity into a window into the past, revealing how ancient ecosystems and landscapes evolved over time.

Drying Time for Pressure Treated Wood: What to Expect

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Fossilization Stages: Includes permeation, permineralization, and complete replacement of wood structure

Petrified wood, a captivating fossilized remnant of ancient forests, undergoes a meticulous transformation over millennia. The process begins with permeation, where groundwater rich in minerals seeps into the porous structure of fallen wood. This initial stage is crucial, as it sets the foundation for the subsequent mineralization. Imagine a tree trunk submerged in sediment, its cellular cavities gradually filled with water laden with silica, calcite, or pyrite. Without this permeation, the wood would simply decay, leaving no trace of its existence.

Next comes permineralization, the stage where the real magic happens. As the mineral-rich water evaporates or cools, dissolved minerals precipitate out, crystallizing within the wood’s cellular structure. This process preserves the wood’s original texture, often in stunning detail, from growth rings to individual cells. For instance, silica, commonly found in petrified wood, forms quartz crystals that harden the wood into stone. This stage can take thousands to millions of years, depending on the mineral concentration and environmental conditions. Patience is key—nature’s artistry is not rushed.

The final stage is complete replacement, where the organic material of the wood is entirely replaced by minerals, leaving behind a rock-hard replica. This is not mere preservation but a metamorphosis. The original wood’s carbon is often replaced by minerals like silica or calcite, molecule by molecule, while retaining the wood’s original shape and structure. A practical tip for identifying this stage: true petrified wood will scratch glass due to its high quartz content, unlike ordinary wood or mineral-coated fossils.

Comparatively, other fossilization processes, like carbonization or mold formation, preserve only the wood’s imprint or carbon residue. Petrification, however, is unique in its ability to replicate the wood’s structure in three dimensions. This distinction highlights why petrified wood is both scientifically valuable and aesthetically prized.

In conclusion, the journey from fallen tree to petrified wood is a testament to time and chemistry. Each stage—permeation, permineralization, and complete replacement—is a critical step in transforming organic matter into a durable mineral replica. Understanding these processes not only deepens appreciation for these ancient relics but also underscores the intricate interplay between geology and biology. Whether you’re a collector, geologist, or nature enthusiast, petrified wood offers a tangible connection to Earth’s distant past.

Wood Rot Timeline: Factors Affecting Decay and Prevention Tips

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Petrified wood formation typically takes millions of years, often ranging from 5 to 50 million years, depending on environmental conditions.

The time required for petrification depends on factors like the presence of silica-rich water, temperature, pressure, and the type of wood. Faster petrification occurs in environments with abundant minerals and stable conditions.

While rare, partial petrification can occur in as little as tens of thousands of years under ideal conditions, but complete petrification still generally requires millions of years.