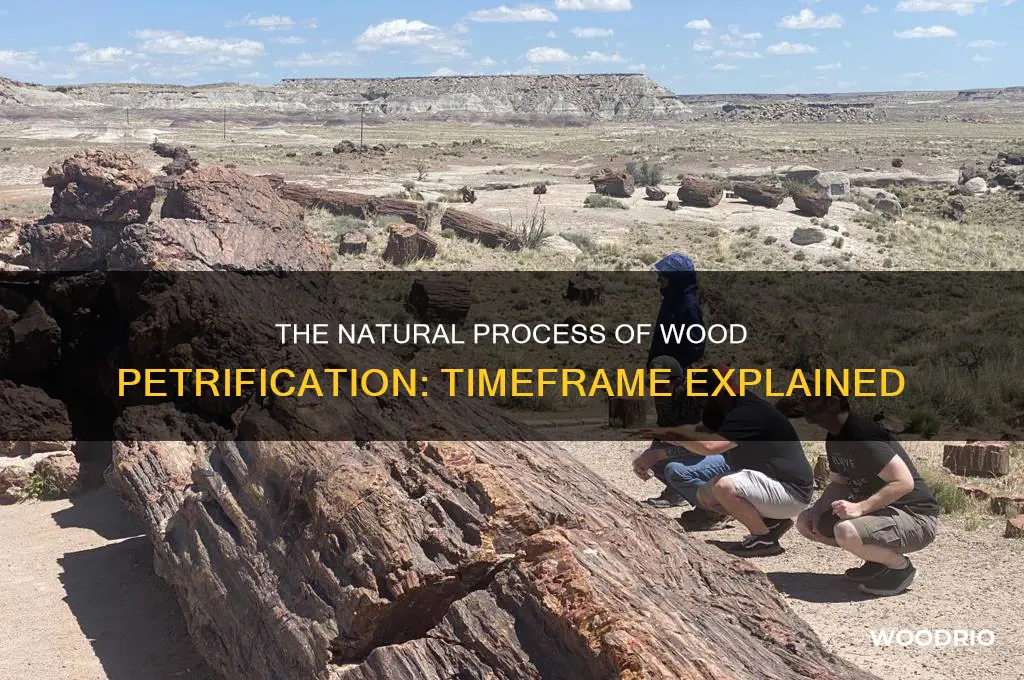

Petrification, the process by which wood transforms into stone, is a fascinating yet slow natural phenomenon that occurs over millions of years. It begins when wood becomes buried under sediment, protecting it from decay and allowing minerals like silica, calcite, or pyrite to gradually infiltrate its cellular structure. Over time, these minerals replace the organic material, preserving the wood’s original texture and structure while turning it into a stone-like substance. The exact duration of petrification varies depending on factors such as the mineral content of the surrounding environment, temperature, and pressure, but it typically takes at least 10 million years for wood to fully petrify in nature. This process results in stunning fossilized wood, known as petrified wood, which offers valuable insights into ancient ecosystems and geological history.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Average Time for Petrification | 10,000 to 1 million years |

| Key Factors Influencing Speed | Burial depth, mineral-rich groundwater, lack of oxygen, type of wood |

| Initial Stage (Permineralization) | 100 to 1,000 years (cell walls replaced by minerals like silica or calcite) |

| Complete Petrification | 100,000+ years (full transformation into stone) |

| Optimal Conditions | Volcanic ash or sediment burial, consistent mineral supply |

| Preservation of Original Structure | Cell structure often preserved due to slow mineral replacement |

| Common Minerals Involved | Quartz, calcite, pyrite, opal |

| Notable Examples | Petrified Forest National Park (Arizona, USA) - 225 million years old |

| Rarity of Complete Petrification | Rare; most wood decays before full petrification occurs |

Explore related products

$64.57 $77.99

What You'll Learn

Factors affecting petrification rate

Petrification, the process by which wood transforms into stone, is a geological marvel influenced by a complex interplay of environmental factors. Understanding these factors is crucial for anyone curious about the timeline of this natural phenomenon. The rate at which wood petrifies can vary dramatically, from thousands to millions of years, depending on conditions such as mineral availability, water composition, temperature, and pressure. Each of these elements plays a distinct role in determining how quickly organic matter transitions into a mineralized state.

Mineral Availability: The Building Blocks of Petrification

The presence of dissolved minerals in groundwater is essential for petrification. Silica, calcite, and pyrite are among the most common minerals involved, with silica (quartz) being the primary component in most petrified wood. The concentration of these minerals in the surrounding water directly impacts the rate of petrification. For instance, wood buried in silica-rich volcanic ash or sediment will petrify faster than wood in mineral-poor environments. Practical tip: Areas with geothermal activity or mineral-rich sedimentary basins are ideal for observing rapid petrification.

Water Composition and Flow: The Catalyst for Mineral Transport

Water acts as the medium through which minerals are transported into the wood’s cellular structure. The pH, salinity, and flow rate of groundwater influence how effectively minerals can penetrate and replace organic material. Acidic water, for example, can accelerate the breakdown of wood fibers, making it easier for minerals to infiltrate. Conversely, stagnant water may slow the process by limiting mineral circulation. Caution: Wood exposed to highly alkaline or saline water may degrade without petrifying, as these conditions can hinder mineral deposition.

Temperature and Pressure: The Geological Timekeepers

Temperature and pressure are critical factors in petrification, often dictating the pace of mineralization. Higher temperatures generally accelerate chemical reactions, including those involved in petrification, but extreme heat can also cause wood to decompose before mineralization occurs. Pressure, typically from overlying sediment, helps compact the wood and facilitates mineral infiltration. For example, wood buried deep within sedimentary layers under moderate heat and pressure will petrify more efficiently than wood exposed to surface conditions. Takeaway: Optimal petrification occurs in environments with stable, moderate temperatures and gradual increases in pressure.

Biological Activity: The Unseen Influencer

Microorganisms and fungi can either hinder or aid petrification. Decomposers break down wood rapidly, leaving little structure for minerals to replace. However, some bacteria can promote mineralization by creating conditions favorable for mineral deposition. For instance, iron-oxidizing bacteria can enhance the formation of iron-rich minerals in wood. Comparative analysis: Wood in oxygen-poor environments, such as deep burial sites, is less likely to be affected by decomposers, increasing the chances of successful petrification.

In summary, petrification is not a one-size-fits-all process. By considering factors like mineral availability, water composition, temperature, pressure, and biological activity, one can better predict the timeline of wood’s transformation into stone. Whether you’re a geologist, fossil enthusiast, or simply curious about Earth’s processes, understanding these factors provides valuable insights into the natural history preserved in petrified wood.

Wagner's Quick Remarriage: Timing After Natalie Wood's Tragic Death

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Role of mineral-rich water in process

Mineral-rich water acts as the alchemist in the petrification process, transforming organic wood into stone-like fossils over millennia. This water, often saturated with dissolved minerals like silica, calcite, and pyrite, seeps into the cellular structure of buried wood. As the water evaporates or cools, it deposits these minerals, gradually replacing the wood’s organic matter with crystalline structures. Without this mineral-laden water, petrification would remain an impossibility, leaving wood to decay rather than fossilize.

Consider the steps this water must take to initiate petrification. First, it must infiltrate the wood, a process facilitated by the wood’s porous nature. Over time, the minerals in the water precipitate, filling cell walls and cavities. This requires a stable environment—one where the water’s flow is slow and consistent, allowing minerals to accumulate without being washed away. For example, wood buried in sedimentary basins or volcanic ash layers often has access to such water, explaining why these environments yield the most spectacular petrified wood specimens.

The mineral composition of the water dictates the final appearance and durability of the petrified wood. Silica-rich water, for instance, produces chalcedony or quartz-filled fossils, known for their glass-like luster and hardness. Calcite-rich water results in softer, more brittle fossils. The concentration of minerals in the water also matters; higher concentrations accelerate the petrification process but can lead to uneven mineralization if not balanced by consistent flow. Practical tip: Geologists often analyze the mineral content of water in fossil-rich areas to predict the type and quality of petrified wood they might uncover.

While mineral-rich water is essential, its role is not without challenges. Rapid mineral deposition can cause cracking or warping in the wood, as the expanding crystals exert pressure on the organic structure. Additionally, if the water’s mineral content fluctuates drastically, the petrification process may stall or produce inconsistent results. Caution: Amateur fossil hunters should avoid attempting to accelerate petrification artificially, as introducing minerals too quickly can destroy the wood’s integrity.

In conclusion, mineral-rich water is the unsung hero of petrification, driving the transformation of wood into stone through a delicate interplay of chemistry and time. Its presence, composition, and behavior determine whether wood decays or endures as a fossil. Understanding its role not only deepens our appreciation for these ancient relics but also guides efforts to preserve and study them effectively. Without this water, the Earth’s geological record would be far poorer, lacking the vibrant, mineralized remnants of forests past.

Optimal Timing: Applying Oil to Teak Wood Post Pressure Washing

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Impact of burial depth on time

The depth at which wood is buried significantly influences the duration of its petrification process. Shallow burial, typically less than 10 feet, exposes wood to fluctuating environmental conditions, such as temperature changes and oxygen exposure, which slow mineralization. Deeper burial, beyond 30 feet, shields wood from these variables, creating a more stable environment conducive to faster petrification. This depth gradient underscores the interplay between geological stability and the rate of fossilization.

Consider the steps involved in optimizing burial depth for petrification. For experimental or educational purposes, burying wood at a depth of 20 to 30 feet mimics ideal natural conditions, as this range minimizes oxygen intrusion while maintaining sufficient pressure for mineral infiltration. Avoid depths less than 5 feet, as surface-level burial risks decay from microorganisms and weathering. Conversely, depths exceeding 50 feet may require specialized equipment and pose logistical challenges without significantly accelerating the process.

A comparative analysis reveals that wood buried at intermediate depths (15–25 feet) petrifies within 1,000 to 10,000 years, whereas shallow burial can extend this timeline to 50,000 years or more. For instance, the petrified forests of Arizona showcase wood buried at varying depths, with deeper specimens exhibiting more advanced mineralization. This highlights the inverse relationship between burial depth and petrification time, a principle applicable to both natural and controlled settings.

Practical tips for enthusiasts include selecting burial sites with consistent sediment composition, such as fine-grained silt or clay, which enhance mineral permeability. Monitor pH levels, aiming for a neutral to slightly alkaline environment (pH 7–8.5), as acidity can hinder silica deposition. For accelerated results, consider pre-treating wood with mineral-rich solutions before burial, though this method remains experimental and may alter authenticity.

In conclusion, burial depth acts as a critical determinant in the petrification timeline, with deeper interment yielding faster results due to reduced environmental interference. By understanding this relationship, researchers and hobbyists can strategically manipulate conditions to study or replicate this geological process more efficiently. Whether for scientific inquiry or artistic endeavor, mastering the impact of depth transforms petrification from a passive observation into an active, measurable phenomenon.

Maximizing Grill Efficiency: Wood Pellet Lifespan and Usage Tips

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$6.99

Influence of wood type on duration

The type of wood significantly influences the duration of petrification, a process where organic material transforms into stone through mineralization. Hardwoods, such as oak or hickory, tend to petrify more slowly than softwoods like pine or cedar. This disparity arises from their cellular structure: hardwoods have denser, more complex cell walls that resist decay but also slow mineral infiltration. Softwoods, with their simpler, less dense structure, allow minerals to permeate more quickly, often leading to faster petrification under ideal conditions.

Consider the environment in which petrification occurs. For instance, a pine log buried in a silica-rich volcanic ash deposit might fully petrify within 5,000 to 10,000 years, while an oak log in the same environment could take 20,000 years or more. The key lies in the wood’s porosity and its ability to interact with surrounding minerals. Practical tip: if you’re attempting artificial petrification, choose softwoods for faster results, but ensure the mineral solution (e.g., a mixture of silica and water) is consistently applied over time.

Analyzing specific examples highlights this variation. The Petrified Forest National Park in Arizona showcases both hardwood and softwood fossils, with conifers (softwoods) often exhibiting more detailed preservation due to their quicker mineralization. In contrast, hardwood fossils in the same area are rarer and less detailed, suggesting a longer, more gradual process. This observation underscores the importance of wood type in determining petrification timelines.

To expedite petrification, experiment with wood density and mineral exposure. For instance, drilling small holes into denser hardwoods can increase their surface area, allowing minerals to penetrate more effectively. Alternatively, submerging softwoods in a high-concentration silica solution (50-70% saturation) can accelerate the process to a few decades, though this is still significantly longer than natural conditions. Caution: artificial methods require precise control to avoid uneven mineralization, which can compromise the fossil’s integrity.

In conclusion, the influence of wood type on petrification duration is a critical factor in both natural and artificial settings. By understanding the structural differences between hardwoods and softwoods, enthusiasts and researchers can better predict outcomes and tailor methods to achieve desired results. Whether studying ancient fossils or creating new ones, this knowledge ensures a more informed and efficient approach to the petrification process.

Charcoal vs. Wood: Which Burns Longer for Your Fire Needs?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Typical timeframes for natural petrification

Petrification, the process by which organic materials like wood turn into stone, is a marvel of geological patience. It typically takes millions of years for wood to fully petrify under natural conditions. This transformation occurs when wood is buried in sediment rich in minerals, such as silica or calcite, and groundwater permeates the material, gradually replacing its organic structure with mineral deposits. The exact timeframe varies widely depending on environmental factors, but the process is universally characterized by its extraordinary slowness.

To understand the typical timeframes, consider the conditions required for petrification. The wood must be shielded from decay, often by rapid burial in environments like volcanic ash, mud, or river sediments. Once buried, the rate of mineralization depends on the concentration of minerals in the surrounding water, temperature, and pressure. For instance, wood buried in silica-rich environments, such as those found near volcanic activity, may petrify faster than wood in calcite-rich settings. Despite these variations, the process rarely occurs in less than 10,000 years and often stretches into the millions-of-years range.

A notable example is the Petrified Forest National Park in Arizona, where logs dating back to the Late Triassic period, approximately 225 million years ago, have been fully transformed into quartz. This example underscores the immense timescale involved in petrification. While such extreme durations are common, smaller or more mineral-rich specimens may petrify in a "shorter" timeframe of 100,000 to 500,000 years. However, these are still geological blinks compared to human lifespans.

For those curious about accelerating petrification artificially, modern techniques can reduce the process to months or years by using high-pressure mineral solutions. However, natural petrification remains a testament to the Earth’s slow, relentless processes. Its typical timeframe serves as a reminder of the vast difference between human and geological timescales, making each petrified specimen a window into deep history.

Durability of Wooden Baseball Bats: Lifespan and Maintenance Tips

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The process of wood petrification, or fossilization, typically takes millions of years, often ranging from 5 to 50 million years, depending on environmental conditions.

Key factors include the presence of mineral-rich water, stable burial conditions, and the absence of oxygen, which together facilitate the slow replacement of organic material with minerals like silica or calcite.

While natural petrification is a slow process, human-assisted methods, such as using pressurized mineral solutions, can accelerate petrification to a matter of months or years, though this is not considered natural petrification.