Petrification, the process by which wood transforms into stone, is a fascinating geological phenomenon that occurs over millions of years. It begins when a tree is buried under sediment, such as mud, volcanic ash, or sand, which shields it from decay and oxygen. Over time, groundwater rich in minerals like silica, calcite, or pyrite seeps into the wood, gradually replacing the organic material cell by cell with these minerals. This slow mineralization process preserves the wood’s original structure, often with remarkable detail, while turning it into a stone-like substance. The duration of petrification varies widely, typically ranging from 5 million to 50 million years, depending on factors like the mineral content of the surrounding environment, temperature, and pressure. The result is a fossilized wood, known as petrified wood, that retains the texture and patterns of the original tree but is now as hard and durable as stone.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Process Name | Petrification (Permineralization) |

| Timeframe | Typically millions of years (10 million years or more) |

| Key Factors Influencing Speed | - Mineral-rich water availability - Burial depth and pressure - Type of wood (hardwoods petrify faster) - Environmental conditions (stable, anaerobic environments) |

| Initial Stage | Preservation (wood buried in sediment, protected from decay) |

| Mineral Replacement | Silica (quartz), calcite, pyrite, or other minerals replace organic matter |

| Cellular Structure Retention | Original cell structure often preserved in fine detail |

| Common Locations | Areas with volcanic ash, riverbeds, or mineral-rich groundwater |

| Notable Examples | Petrified Forest National Park (Arizona, USA) - ~225 million years old |

| Human-Accelerated Petrification | Possible in labs (months to years) using high-pressure mineral solutions |

| Distinguishing Feature | Wood turns into stone while retaining its original texture and structure |

Explore related products

$64.57 $77.99

What You'll Learn

Factors Affecting Petrification Speed

Petrification, the process by which wood transforms into stone, is not a uniform or predictable timeline. It’s a geological alchemy influenced by a constellation of factors, each playing a role in determining how swiftly organic matter becomes mineralized. Among these, the mineral composition of the surrounding environment stands out as a critical determinant. Silica-rich waters, for instance, accelerate petrification by infiltrating cellular structures and precipitating quartz, a process observed in iconic sites like the Petrified Forest National Park. In contrast, environments lacking silica or dominated by calcite may yield slower, less complete fossilization. This mineral dependency underscores the importance of location in shaping the petrification timeline.

Another pivotal factor is the pH level of the water involved in the process. Neutral to slightly alkaline conditions (pH 7–8.5) are ideal for silica polymerization, the chemical reaction that replaces organic material with minerals. Acidic waters, however, can dissolve wood before mineralization occurs, while highly alkaline environments may precipitate minerals too rapidly, resulting in a brittle, less detailed fossil. For enthusiasts attempting experimental petrification, maintaining a controlled pH range is essential—a task achievable with buffers like sodium bicarbonate or acetic acid in laboratory settings.

Temperature and pressure also exert significant influence, though their effects are often intertwined with geological timescales. Higher temperatures (50–100°C) in buried environments can expedite silica gel formation, as seen in geothermal areas. Yet, this process requires millennia, not years, highlighting the challenge of replicating such conditions artificially. Pressure, typically from overlying sediment, aids in compacting wood and facilitating mineral infiltration, but its impact is gradual and dependent on depth. For those studying petrification, these variables serve as reminders of the process’s inherent slowness and its reliance on natural forces.

Finally, the type of wood itself cannot be overlooked. Dense, resinous woods like pine or redwood petrify more readily due to their natural resistance to decay and their ability to retain structural integrity during mineralization. Softer woods, such as balsa, often disintegrate before significant petrification occurs. This biological predisposition means that not all wood is destined for stone—a fact that fossil hunters and paleontologists consider when evaluating potential sites. Understanding these factors collectively reveals petrification not as a singular event, but as a dynamic interplay of chemistry, geology, and biology, each contributing to the transformation’s pace and outcome.

Mr. Garrison's Woodland Life: Duration and Survival Story Explored

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Role of Minerals in Wood Fossilization

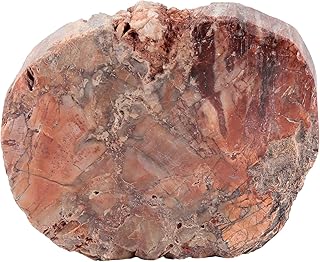

Minerals are the silent architects of wood petrification, transforming organic matter into stone through a meticulous process that spans millennia. This natural alchemy begins when wood is buried under sediment, shielding it from decay. Groundwater rich in dissolved minerals like silica, calcite, and pyrite seeps into the wood’s cellular structure, gradually replacing organic material with inorganic compounds. Over time, the wood’s original texture and even its growth rings are preserved, but its composition becomes entirely mineral-based. This mineralization is not merely a coating; it is a molecular takeover, where cellulose and lignin are methodically substituted by harder, more durable substances.

The type and concentration of minerals in the surrounding environment dictate the outcome of petrification. Silica, for instance, is the most common mineral involved, often derived from volcanic ash or sandstone. When silica-rich water permeates wood, it forms quartz, a crystalline mineral that replicates the wood’s cellular structure with astonishing fidelity. In contrast, calcite, a form of calcium carbonate, can create a more opaque, chalky appearance. Pyrite, or fool’s gold, may infiltrate wood in iron-rich environments, lending a metallic sheen. Each mineral imparts unique characteristics, turning petrified wood into a geological fingerprint of its formation conditions.

Time is both the ally and adversary of this process. While petrification requires thousands to millions of years, the rate at which minerals replace organic material varies widely. Factors such as temperature, pressure, and mineral concentration play critical roles. For example, wood buried in hot springs or deep sedimentary basins may petrify faster due to higher mineral solubility and geothermal activity. Conversely, wood in cooler, less mineralized environments may take significantly longer. This variability underscores the importance of patience in nature’s workshop, where time is measured in epochs, not hours.

Practical observation of petrified wood reveals the artistry of mineralization. In Arizona’s Petrified Forest National Park, logs transformed into quartz-rich specimens exhibit vibrant hues of red, yellow, and purple, a result of trace minerals like iron and manganese. In contrast, petrified wood from iron-rich regions often appears darker, almost metallic. For enthusiasts and collectors, identifying the minerals present in a specimen can provide insights into its geological history. A simple test using a drop of dilute hydrochloric acid can confirm the presence of calcite (which fizzes) or quartz (which remains inert).

Understanding the role of minerals in wood fossilization offers more than scientific curiosity; it provides a lens into Earth’s history. Each piece of petrified wood is a time capsule, preserving not only the structure of ancient trees but also the chemical signature of the environment in which it was entombed. For educators and hobbyists, this process highlights the interconnectedness of biology and geology, demonstrating how life and rock are bound in an eternal dance. By studying mineralization, we gain a deeper appreciation for the forces that shape our planet and the relics they leave behind.

Wood Frog Egg Hatching Timeline: From Spawn to Tadpole

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Timeframe for Complete Petrification

Petrification, the process by which wood transforms into stone, is a geological marvel that unfolds over vast timescales. Unlike quick-setting concrete or rapid biological processes, this transformation demands patience on a scale that defies human intuition. The journey from organic matter to mineralized fossil typically spans millions of years, with the exact duration hinging on environmental conditions and the specific minerals involved. For instance, silica-rich environments, such as ancient riverbeds or volcanic ash deposits, accelerate the process by providing the necessary minerals for cell-by-cell replacement. However, in less optimal settings, petrification can stretch even longer, underscoring the profound interplay between time and geology.

To understand the timeframe, consider the steps involved. First, the wood must be buried rapidly to shield it from decay, often in sediment-rich environments like swamps or river deltas. Next, groundwater saturated with dissolved minerals—primarily silica, calcite, or pyrite—permeates the wood, gradually replacing its organic structure with inorganic compounds. This mineralization process occurs at a glacial pace, with estimates suggesting it takes 10,000 to several million years for complete petrification. For example, the iconic petrified wood found in Arizona’s Petrified Forest National Park dates back to the Triassic Period, approximately 225 million years ago, highlighting the extraordinary duration required for such transformation.

Environmental factors play a pivotal role in dictating the pace of petrification. High mineral concentrations in groundwater expedite the process, as do elevated temperatures and pressures, which enhance chemical reactivity. Conversely, low mineral availability or fluctuating environmental conditions can stall progress, prolonging the timeline indefinitely. This variability means that while some specimens petrify within a few million years, others may require tens of millions. Practical tips for identifying petrified wood include its weight (significantly heavier than regular wood) and its ability to scratch glass due to its quartz content.

Comparatively, petrification stands in stark contrast to other fossilization processes. For instance, carbonization, which preserves organic material as a thin carbon film, can occur in as little as thousands of years. Permineralization, a broader category that includes petrification, varies widely depending on the material being fossilized. However, petrification’s uniqueness lies in its complete transformation of organic matter into stone, a process that demands not just time but the right geological conditions. This distinction underscores why petrified wood is both rare and scientifically invaluable.

In conclusion, the timeframe for complete petrification is a testament to Earth’s geological patience. While the process can vary from 10,000 to over 200 million years, it consistently requires a delicate balance of burial, mineral-rich groundwater, and stable environmental conditions. For enthusiasts and collectors, understanding this timeline not only deepens appreciation for these ancient relics but also guides efforts to preserve and study them. Whether unearthed in a desert or displayed in a museum, petrified wood serves as a tangible link to Earth’s distant past, its formation a story written in stone over epochs.

Wood Flowers Lifespan: Durability, Care Tips, and Longevity Explained

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$6.99

Environmental Conditions Needed for Petrification

Petrification, the process by which wood transforms into stone, is not a swift or common occurrence. It demands a precise set of environmental conditions, each playing a critical role in preserving and mineralizing organic matter. The first requirement is burial in sediment, which shields the wood from decay and erosion. This protective layer, often composed of mud, sand, or volcanic ash, must be deep enough to isolate the wood from oxygen and biological activity. Without this initial step, the wood would decompose before mineralization could begin.

Once buried, the presence of mineral-rich groundwater becomes essential. This water acts as a transport medium, carrying dissolved minerals like silica, calcite, and pyrite to the wood. The rate of mineralization depends on the concentration of these minerals and the flow rate of the water. For instance, silica-rich water, often found in volcanic or geothermal areas, accelerates petrification. However, the water must flow slowly enough to allow minerals to precipitate into the wood’s cellular structure, a process that can take thousands of years.

Anaerobic conditions are another critical factor. Oxygen promotes decay by supporting microorganisms that break down organic material. In an oxygen-depleted environment, such as deep underground or in waterlogged sediments, decay slows dramatically. This preservation allows the wood’s cellular structure to remain intact, providing a template for mineralization. For example, petrified forests like those in Arizona formed in ancient river systems where logs were rapidly buried in sediment, cutting off oxygen supply.

Finally, geological stability over extended periods is necessary. Petrification requires millions of years, during which the buried wood must remain undisturbed by tectonic activity, erosion, or changes in groundwater chemistry. Areas with stable geological histories, such as sedimentary basins or volcanic plains, are ideal. Conversely, regions prone to earthquakes or uplift expose buried wood to surface conditions, halting the petrification process.

To summarize, petrification demands a unique combination of burial, mineral-rich groundwater, anaerobic conditions, and geological stability. Each factor must align over vast timescales, making petrified wood a rare and fascinating natural phenomenon. Understanding these conditions not only sheds light on Earth’s history but also highlights the delicate balance required for such transformations to occur.

Perfectly Crispy Chicken of the Woods: Frying Time Guide

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Differences Between Petrified Wood and Regular Fossils

Petrified wood and regular fossils both offer windows into Earth’s ancient past, yet their formation processes and resulting characteristics differ significantly. Petrified wood forms through a process called permineralization, where minerals gradually replace the organic material of the wood cell by cell, preserving its original structure in stone. This transformation typically takes thousands to millions of years, depending on environmental conditions such as mineral-rich water and stable burial. Regular fossils, on the other hand, encompass a broader range of preservation methods, including compression, carbonization, and mold or cast formation, which often result in less detailed preservation of the original organism.

Consider the visual and tactile differences. Petrified wood retains the wood’s original texture, growth rings, and even cellular details, making it a stunning example of nature’s artistry. It is heavy, durable, and often exhibits vibrant colors due to trace minerals like iron, manganese, and copper. Regular fossils, however, vary widely in appearance. Compression fossils, like those of leaves, are thin and flat, while mold and cast fossils replicate the external shape of an organism without preserving internal structures. These differences highlight the unique conditions required for each type of fossilization.

The timeframes for petrification versus other fossilization processes also diverge. Petrification demands a specific set of circumstances—consistent mineral-rich water flow, low oxygen levels, and stable burial—which can extend the process over millions of years. For instance, the petrified wood found in Arizona’s Petrified Forest National Park took over 200 million years to form. In contrast, some regular fossils, such as those preserved through rapid burial or amber entrapment, can form in a matter of centuries or even decades. This disparity underscores the rarity and uniqueness of petrified wood.

Practical considerations further distinguish the two. Petrified wood is highly sought after by collectors and is often polished or carved into decorative items, whereas regular fossils, particularly delicate ones like insect inclusions in amber, require careful handling to prevent damage. For enthusiasts, understanding these differences can guide preservation efforts and appreciation. For example, petrified wood can withstand outdoor display, while compression fossils may degrade when exposed to moisture or sunlight.

In summary, while both petrified wood and regular fossils are testaments to Earth’s history, their formation mechanisms, preservation details, and practical uses set them apart. Petrified wood’s meticulous mineral replacement process results in a durable, visually striking artifact, whereas regular fossils showcase a variety of preservation methods, each with its own limitations and strengths. Recognizing these distinctions enriches our understanding of paleontology and enhances the value of these ancient treasures.

Wood Duck Fledglings: Water Duration and Survival Insights

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The process of wood petrification, or permineralization, typically takes thousands to millions of years, depending on environmental conditions.

Factors such as the presence of mineral-rich water, stable burial conditions, and the absence of oxygen accelerate petrification, but it still requires immense time.

While rare, wood can petrify more quickly (within a few hundred years) in environments with extremely high mineral concentrations, such as hot springs or volcanic ash deposits.

Yes, petrified wood is completely transformed into stone as minerals replace the organic material cell by cell, preserving its original structure.