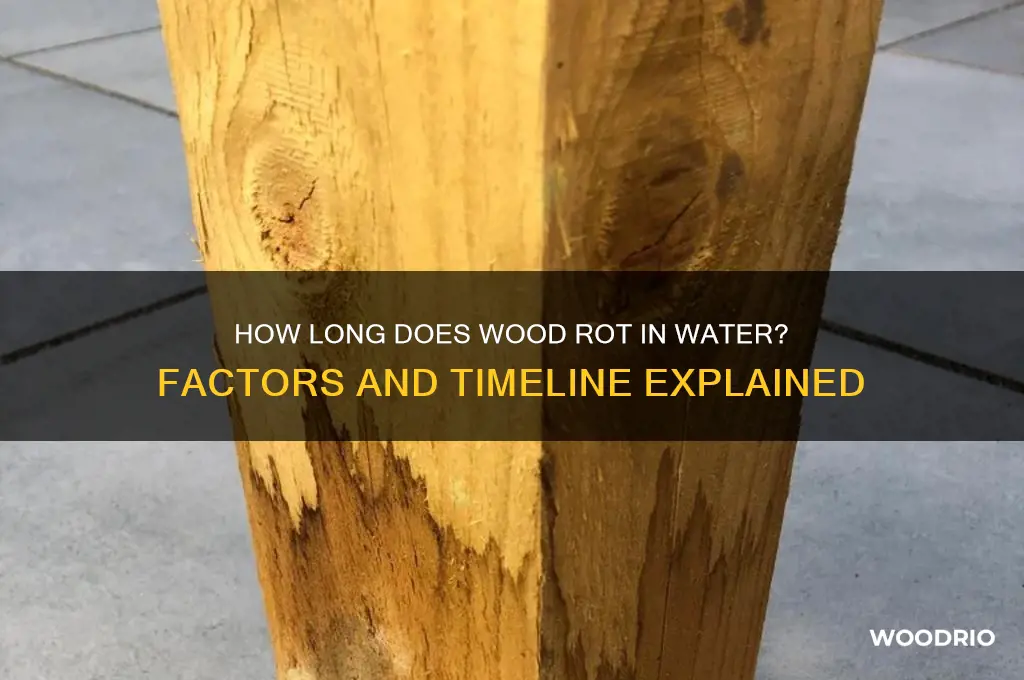

Wood rot from water exposure is a gradual process influenced by several factors, including the type of wood, moisture levels, temperature, and the presence of fungi. Softwoods, like pine, tend to decay faster than hardwoods, such as oak, due to their lower density and higher susceptibility to fungal growth. In consistently wet conditions, wood can begin to show signs of rot within a few months, with significant deterioration occurring within one to two years. However, in environments with intermittent moisture or proper ventilation, the process can take much longer, sometimes spanning several years or even decades. Preventative measures, such as sealing or treating the wood, can significantly slow down the rotting process.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Type of Wood | Hardwoods (e.g., oak, teak) last longer than softwoods (e.g., pine). |

| Moisture Content | Constantly wet wood rots faster (weeks to months) than intermittently wet wood (months to years). |

| Oxygen Exposure | Wood submerged in water (anaerobic) rots slower than wood exposed to air and water (aerobic). |

| Temperature | Warmer temperatures (above 70°F/21°C) accelerate rot (weeks to months), while colder temperatures slow it (years). |

| Presence of Fungi/Insects | Wood exposed to fungi (e.g., mold, mildew) or insects (e.g., termites) rots faster (weeks to months). |

| Treatment/Preservatives | Treated wood (e.g., pressure-treated, sealed) lasts significantly longer (10+ years) than untreated wood. |

| Environment | Wood in stagnant water rots faster than in flowing water. |

| Wood Density | Denser wood resists rot longer than less dense wood. |

| Typical Rot Time (Untreated) | 2–5 years in ideal conditions; can be as fast as 6 months or as slow as 10+ years. |

| Typical Rot Time (Treated) | 10–30+ years depending on treatment quality and environmental factors. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Factors accelerating wood decay

Wood decay is a natural process, but certain factors can significantly accelerate it, especially when water is involved. One of the primary accelerants is moisture content. Wood with a moisture content above 20% is highly susceptible to decay, as this level creates an ideal environment for fungi and bacteria to thrive. For instance, untreated lumber exposed to constant rain or submerged in water can begin to rot within 6 months to 2 years, depending on the wood species and environmental conditions. To mitigate this, ensure wood used in wet environments is either treated with preservatives or naturally resistant species like cedar or redwood are chosen.

Another critical factor is oxygen availability. While it might seem counterintuitive, wood in waterlogged conditions with limited oxygen can still decay rapidly due to anaerobic bacteria. However, the presence of oxygen accelerates decay by fostering the growth of aerobic fungi, which are more aggressive in breaking down cellulose and lignin. For example, wood partially submerged in stagnant water, where oxygen can intermittently reach the surface, often decays faster than fully submerged wood. To slow this process, consider using waterproof barriers or coatings that limit oxygen exposure while managing moisture.

Temperature plays a pivotal role in accelerating wood decay, particularly in warm environments. Fungi and bacteria responsible for wood rot thrive in temperatures between 70°F and 90°F (21°C to 32°C). In tropical climates, wood exposed to water can rot in as little as 3 to 6 months, compared to 1 to 2 years in cooler regions. If you’re working in warmer areas, prioritize using pressure-treated wood or applying fungicidal treatments to extend its lifespan. Additionally, proper ventilation can help reduce heat buildup, slowing the decay process.

The pH level of the surrounding environment also influences wood decay. Acidic conditions, such as those found in soil with a pH below 5.5, can weaken wood fibers and make them more susceptible to fungal attack. Conversely, alkaline environments can slow decay but are less common in natural settings. If wood is in contact with soil, test the pH and amend it if necessary to create a less hospitable environment for decay organisms. Applying lime to acidic soil, for instance, can raise the pH and provide some protection.

Finally, insect activity can exacerbate wood decay by creating entry points for moisture and fungi. Termites, carpenter ants, and wood-boring beetles weaken wood structures, making them more vulnerable to water damage and rot. Regular inspections and treatments, such as insecticidal sprays or borate-based preservatives, can prevent infestations. For outdoor structures, elevate wood at least 6 inches above ground level to reduce contact with insects and moisture, significantly slowing decay.

By addressing these factors—moisture, oxygen, temperature, pH, and insects—you can effectively prolong the life of wood exposed to water, ensuring durability even in challenging environments.

Turning a Wooden Bowl: Timeframe and Techniques for Crafting Perfection

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Types of wood resistance levels

Wood's resistance to rot from water exposure varies dramatically based on species, with some lasting decades while others succumb within months. This disparity hinges on natural oils, resins, and density, which act as barriers against moisture infiltration and fungal growth. For instance, teak and cedar contain high levels of protective oils, granting them exceptional durability in wet conditions. Conversely, pine and spruce, lacking these defenses, deteriorate rapidly without treatment. Understanding these inherent properties is crucial for selecting wood suited to specific environments, whether for outdoor furniture, decking, or structural elements.

To maximize wood longevity, consider both natural resistance and external treatments. Woods like redwood and cypress fall into the moderately resistant category, benefiting significantly from sealants or pressure treatment. For high-moisture areas, such as bathrooms or waterfront structures, opt for naturally resistant species or invest in preservative treatments like creosote or copper azole. These treatments penetrate the wood, inhibiting fungal and insect damage, and can extend lifespan by 20–40 years. However, even treated wood requires periodic maintenance, such as re-sealing every 2–3 years, to sustain its protective barrier.

A comparative analysis reveals that tropical hardwoods, such as ipe and mahogany, outperform softer woods like fir and hemlock in water resistance due to their dense grain and natural chemicals. For example, ipe can last 40+ years in ground contact without treatment, whereas untreated fir may rot within 5–10 years. This makes tropical hardwoods ideal for heavy-duty applications like bridges or piers, despite their higher cost. Conversely, softer woods are better suited for interior use or temporary structures where moisture exposure is minimal.

Practical tips for assessing wood resistance include examining its Janka hardness rating, a measure of density and durability. Woods with a Janka rating above 1,500 lbf, such as oak or maple, generally resist moisture better than those below 900 lbf, like pine. Additionally, inspect the wood’s grain pattern—tighter grains impede water absorption more effectively. For DIY projects, prioritize species with proven track records in wet environments and always apply a water-repellent finish to vulnerable surfaces. By aligning wood selection with its natural resistance level and augmenting it with treatments, you can ensure optimal performance and longevity in any application.

Wooden Toothbrushes: Do They Outlast Plastic Alternatives in Durability?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$4199.99

Impact of moisture content on rot

Wood exposed to moisture is a ticking clock, its lifespan inversely proportional to the water it absorbs. Moisture content above 20% creates a breeding ground for rot-causing fungi. These microscopic invaders thrive in damp environments, secreting enzymes that break down wood's cellulose and lignin, the very building blocks of its strength.

Imagine a wooden beam in a perpetually damp basement. Within months, it might show signs of surface discoloration and softness. Left unchecked, this progresses to cracking, warping, and eventually, structural failure.

The rate of decay isn't linear. Several factors influence the speed at which moisture accelerates rot. Wood species play a crucial role – hardwoods like oak are naturally more resistant than softwoods like pine. The duration and intensity of moisture exposure matter too. Constant saturation is far more damaging than occasional dampness.

Preventing rot hinges on moisture control. Aim for a wood moisture content below 19%. This can be achieved through proper ventilation, waterproofing treatments, and prompt repair of leaks. For existing moisture issues, kiln drying or professional dehumidification may be necessary. Remember, once rot takes hold, it's a race against time to salvage the wood.

Durability of Acacia Wood: Longevity, Maintenance, and Lifespan Explained

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Preventive measures against wood rotting

Wood exposed to moisture is a ticking clock, with rot setting in as quickly as a few months in ideal conditions. While the timeline varies based on wood type, environment, and water exposure, prevention is always faster and cheaper than repair. The key lies in controlling moisture, protecting the wood surface, and fostering an environment hostile to rot-causing fungi.

Here’s how:

Step 1: Seal the Deal with Waterproofing

Apply a high-quality wood sealant or preservative to all exposed surfaces, including end grains, which absorb moisture like sponges. Use copper naphthenate or borate-based treatments for structural wood, following manufacturer guidelines for concentration (typically 1-2% solution) and application frequency (every 2-3 years). For decks and outdoor furniture, opt for marine-grade varnishes or epoxy coatings, reapplying annually in high-humidity regions.

Step 2: Promote Airflow, Block Standing Water

Design structures to shed water effectively. Install drip edges on decks, use pressure-treated lumber for ground contact, and ensure a minimum 6-inch clearance between soil and wood. For indoor spaces, maintain humidity below 50% with dehumidifiers or ventilation fans. In crawl spaces, lay vapor barriers to prevent ground moisture from rising, and inspect gutters biannually to avoid overflow near wooden foundations.

Step 3: Choose Rot-Resistant Materials Strategically

Not all wood is created equal. Naturally rot-resistant species like cedar, redwood, or teak contain tannins and oils that deter fungi. For budget-conscious projects, pressure-treated pine (rated for ground contact) is a reliable alternative. In high-moisture areas, consider composite materials or stainless steel fasteners to eliminate corrosion risks, which can accelerate wood decay.

Caution: Avoid Common Pitfalls

Never stack firewood directly on soil; use pallets or racks to elevate it. Prune vegetation 2 feet away from wooden structures to reduce splashback during rain. Skip painting over untreated wood—moisture will still penetrate, trapping it beneath the surface. Instead, stain or seal before painting for a dual protective layer.

While wood rot can start within months in saturated conditions, preventive measures delay this process by decades. Combine chemical treatments, smart design, and material selection to create a hostile environment for fungi. Regular inspections (annually for outdoor structures, biannually for interiors) catch early signs like discoloration or softness, allowing for spot treatments before rot spreads. With diligence, even the most moisture-prone wood can endure generations.

Understanding the Lifespan of Wood Ticks: How Long Do They Live?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Environmental conditions fostering decay

Wood decay is a complex process influenced by a myriad of environmental factors, each playing a critical role in determining how quickly water-saturated wood will rot. Among these, moisture content stands out as the most pivotal. Wood must reach a moisture level of at least 20% for fungi, the primary agents of decay, to thrive. However, the rate of decay accelerates significantly when moisture levels exceed 30%, creating an ideal environment for fungal colonization. This is why wood in consistently damp conditions, such as near water bodies or in poorly ventilated spaces, deteriorates far more rapidly than wood exposed to intermittent moisture.

Temperature acts as a silent accelerator in this process, with warmer environments fostering faster decay. Fungi responsible for wood rot, such as brown rot and white rot, proliferate most efficiently between 70°F and 90°F (21°C to 32°C). In regions with temperate climates, this means spring and summer months pose the greatest risk for wood decay. Conversely, freezing temperatures can temporarily halt fungal activity, but they do not eliminate the threat; once temperatures rise, decay resumes. For instance, wood in a tropical rainforest, where temperatures are consistently high and humidity is near constant, can show signs of significant decay within 6 months, whereas wood in a colder, drier climate might take several years to exhibit similar damage.

Oxygen availability is another critical factor often overlooked. While fungi require oxygen to metabolize wood, certain anaerobic bacteria can also contribute to decay in oxygen-depleted environments, such as submerged wood. However, the absence of oxygen generally slows the decay process, which is why wood submerged in deep water or buried in soil may take longer to rot compared to wood exposed to air. This principle is leveraged in waterlogged archaeological sites, where ancient wooden structures have survived for centuries due to the oxygen-poor conditions.

The pH level of the surrounding environment also plays a subtle yet significant role. Fungi prefer neutral to slightly acidic conditions, with a pH range of 5.0 to 8.0 being optimal for their growth. Wood in highly acidic or alkaline environments, such as near industrial runoff or in soils with extreme pH levels, may experience slower decay rates. For example, wood exposed to acidic rainwater in industrial areas might take longer to rot compared to wood in a neutral pH environment, despite similar moisture and temperature conditions.

Practical steps can be taken to mitigate these environmental factors and prolong the life of wood. Ensuring proper ventilation reduces moisture accumulation, while applying water-repellent treatments can lower the wood's moisture absorption rate. Storing wood in cooler, drier areas and using fungicides can inhibit fungal growth. For outdoor structures, elevating wood off the ground and using pressure-treated lumber can significantly delay decay. By understanding and manipulating these environmental conditions, it is possible to protect wood from the relentless forces of decay, even in water-prone settings.

Hot Glue Drying Time on Wood: Quick Tips for Crafters

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Wood can begin to rot within 6 months to 2 years when consistently exposed to moisture, depending on factors like wood type, water exposure, and environmental conditions.

No, different wood types rot at varying rates. Softwoods like pine rot faster, while hardwoods like teak or cedar are more resistant and can last longer.

Yes, wood rot can be prevented or slowed by using pressure-treated wood, applying waterproof sealants, ensuring proper drainage, and reducing prolonged moisture exposure.

Warmer temperatures accelerate wood rot by promoting fungal and bacterial growth, while colder temperatures slow down the process but do not completely stop it.