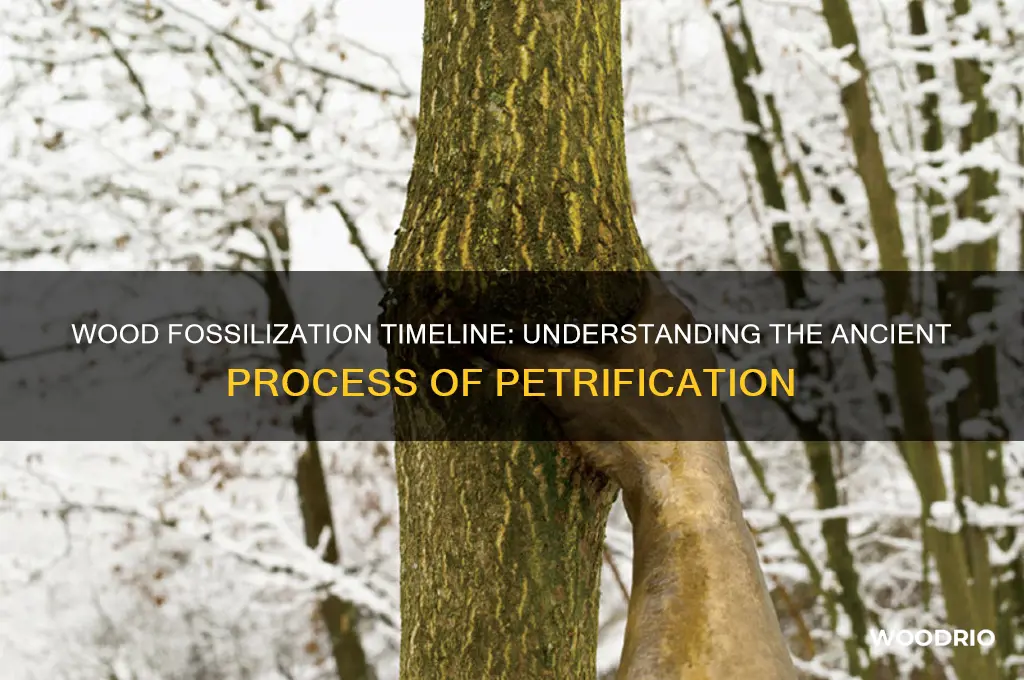

Wood fossilization is a remarkably slow process that can take millions of years, depending on specific environmental conditions. Unlike rapid preservation methods like freezing or mummification, fossilization requires the wood to be buried under sediment, shielding it from decay and oxygen. Over time, minerals gradually replace the organic material in the wood, transforming it into stone-like fossils known as petrified wood. This process typically occurs in environments like riverbeds, swamps, or volcanic ash deposits, where sediment accumulation is high and oxygen is limited. While some stages of fossilization, such as initial burial and mineral infiltration, can begin within centuries, complete petrification often spans 10,000 to 100 million years, making it a testament to Earth’s geological patience.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Time to Fossilize | Typically takes millions of years (10 million years or more) |

| Process | Requires anaerobic conditions (lack of oxygen) and burial in sediment |

| Key Factors | Rapid burial, absence of oxygen, high pressure, and mineral-rich water |

| Stages | 1. Permineralization: Minerals replace organic material. 2. Coalification: Transformation into coal under heat and pressure. |

| Examples | Petrified wood (e.g., Arizona's Petrified Forest, 225 million years old) |

| Preservation Quality | Depends on mineral composition and environmental conditions |

| Common Minerals Involved | Quartz, calcite, pyrite, and other silica-based minerals |

| Role of Water | Groundwater rich in minerals is essential for permineralization |

| Impact of Environment | Swampy, low-oxygen environments are ideal for fossilization |

| Comparison to Other Materials | Wood fossilizes slower than bones or shells due to its organic structure |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Factors Affecting Fossilization Speed: Climate, sediment type, and wood density influence fossilization time

- Permineralization Process: Minerals replace wood cells, taking thousands to millions of years

- Coal Formation Timeline: Wood transforms into coal over 10-300 million years under pressure

- Amber vs. Fossil Wood: Amber forms in decades; fossil wood takes much longer

- Preservation Conditions: Anaerobic environments and rapid burial accelerate fossilization

Factors Affecting Fossilization Speed: Climate, sediment type, and wood density influence fossilization time

Wood fossilization is a race against decay, and climate sets the pace. Tropical environments, with their high temperatures and humidity, accelerate bacterial and fungal activity, leaving wood little chance to fossilize. In contrast, arid regions like deserts offer a slower, more forgiving process. Here, low moisture levels inhibit decomposition, allowing wood to persist long enough for minerals to infiltrate and replace its organic structure. For instance, petrified wood in Arizona’s Petrified Forest National Park formed over millions of years in a dry, sedimentary basin, showcasing how climate can preserve wood for millennia.

Sediment type acts as both a cradle and a catalyst in fossilization. Fine-grained sediments like mud or clay provide a protective blanket, shielding wood from oxygen and scavengers while facilitating mineralization. Coarse sediments, such as sand or gravel, offer less protection and slower mineral infiltration, often resulting in incomplete preservation. Consider the difference between wood buried in a calm lake bed versus a fast-flowing river. The former, encased in fine silt, is more likely to fossilize intact, while the latter may erode or fragment before preservation can occur.

Wood density is the unsung hero of fossilization speed. Dense woods, like oak or teak, resist decay longer due to their compact cell structure, giving minerals more time to replace organic matter. Lighter woods, such as pine or balsa, decompose faster, reducing their chances of fossilization. This is why petrified forests often feature hardwood species, as their density provided a head start in the fossilization race. For practical preservation, burying dense wood in anaerobic, fine-sediment environments mimics ideal fossilization conditions.

To maximize fossilization potential, consider these steps: Choose dense wood species, bury them in fine-grained sediments like clay or mud, and ensure the environment is low in oxygen and moisture. Avoid tropical or highly acidic settings, which accelerate decay. While natural fossilization takes millions of years, these factors can tip the odds in favor of preservation. Whether you’re a paleontologist or a curious enthusiast, understanding these variables transforms fossilization from a mystery into a predictable, if slow, process.

Understanding Wood Lovers Paralysis Duration: Symptoms, Recovery, and Treatment

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Permineralization Process: Minerals replace wood cells, taking thousands to millions of years

Wood fossilization through permineralization is a testament to nature’s patience, where minerals methodically replace organic cells over vast timescales. This process begins when wood is buried in sediment, shielding it from decay. Groundwater rich in dissolved minerals like silica, calcite, or pyrite seeps into the wood’s cellular structure, gradually filling voids left by decomposed organic matter. Over thousands to millions of years, these minerals crystallize, replicating the wood’s original texture and structure with remarkable fidelity. The result? A fossilized log or branch that retains the intricate details of its cellular anatomy, preserved in stone.

Consider the steps involved in this transformation. First, rapid burial is critical to prevent complete decay, often occurring in environments like riverbeds, swamps, or volcanic ash deposits. Next, the wood must be permeable enough to allow mineral-rich water to penetrate its tissues. As minerals precipitate within the cells, they harden, turning the wood into a rock-like material. The type of mineral involved determines the fossil’s appearance—silica creates a glassy, opaque fossil, while pyrite yields a metallic sheen. Each stage is contingent on environmental conditions, from the pH of the surrounding sediment to the mineral composition of the groundwater.

The timescale of permineralization is staggering, often spanning millions of years. For instance, petrified wood found in Arizona’s Petrified Forest National Park dates back over 225 million years, its vibrant quartz-filled cells a testament to the process’s duration. Such examples underscore the rarity of fossilized wood, as most organic material decomposes long before permineralization can occur. Factors like temperature, pressure, and mineral availability dictate the pace, with warmer, more mineral-rich environments accelerating the process. Yet even under ideal conditions, permineralization remains a marathon, not a sprint.

Practical tips for understanding this process include examining petrified wood specimens, which often reveal cross-sections of fossilized cells under magnification. Enthusiasts can also simulate permineralization on a smaller scale by soaking wood in mineral-rich solutions, though this yields only superficial results compared to nature’s work. For educators, using time-lapse animations or geological models can help illustrate the process’s duration and complexity. The takeaway? Permineralization is a slow, meticulous dance between organic matter and minerals, culminating in fossils that bridge deep time and the present.

How Long Do 3-Inch Nails Stay Secure in Wood Before Loosening?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Coal Formation Timeline: Wood transforms into coal over 10-300 million years under pressure

Wood's transformation into coal is a geological marathon, not a sprint, spanning an astonishing 10 to 300 million years. This process, known as coalification, begins with the burial of plant material in oxygen-poor environments like swamps and bogs. Over time, layers of sediment accumulate, subjecting the organic matter to intense heat and pressure. This combination acts as a natural crucible, driving off volatile compounds and leaving behind carbon-rich material. The duration of this process dictates the type of coal formed: shorter periods yield lignite, a brown coal with lower energy content, while longer durations produce bituminous and anthracite coals, denser and more energy-rich.

Understanding this timeline highlights the finite nature of coal reserves, formed over epochs far exceeding human timescales.

Imagine a prehistoric forest, its trees towering and lush. As these giants fall, they become entombed in waterlogged soil, shielded from decay. Microorganisms, starved of oxygen, break down the wood only partially, preserving its cellular structure. This initial stage, peat formation, can take millions of years. As sediments pile up, the pressure increases, squeezing out water and compacting the peat. Heat from the Earth's interior further transforms the material, gradually converting it into lignite, then bituminous coal, and finally, anthracite. Each stage represents a deeper burial, higher temperatures, and a longer duration, ultimately resulting in the black, shiny fuel we extract today.

This journey from forest to fuel illustrates the immense power of geological processes and the vast timescales involved in Earth's history.

The coalification timeline isn't uniform; it's influenced by factors like temperature, pressure, and the original plant material. Higher temperatures and pressures accelerate the process, while different plant types contribute varying amounts of lignin and cellulose, affecting the coal's final composition. For instance, coal formed from ferns and reeds tends to be lower in quality compared to that derived from ancient trees. This variability underscores the complexity of coal formation and the need to consider geological context when assessing coal reserves.

Understanding these factors allows geologists to predict coal quality and quantity, crucial for energy planning and resource management.

The 10 to 300 million year timeframe for coal formation serves as a stark reminder of the non-renewable nature of this resource. Unlike wind or solar power, coal cannot be replenished within human timescales. This realization necessitates a shift towards sustainable energy sources, ensuring a future where energy needs are met without depleting finite resources formed over millennia. The coalification timeline, therefore, is not just a geological curiosity but a call to action, urging us to respect the Earth's history and plan for a sustainable future.

Perfect Timing: When to Use Wood After Placing It in Your Wber

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Amber vs. Fossil Wood: Amber forms in decades; fossil wood takes much longer

The process of fossilization is a race against time, where organic materials battle decomposition to achieve immortality in stone. Yet, not all organic remnants follow the same timeline. Amber, often mistaken for a fossil, forms within decades, preserving ancient life in its golden embrace. In contrast, fossil wood undergoes a centuries-long transformation, turning into stone through mineralization. This stark difference in formation time highlights the unique conditions required for each process, offering a glimpse into Earth’s patient artistry.

Consider the journey of amber: it begins as tree resin, a sticky substance exuded by certain coniferous trees. When resin drips onto a forest floor, it can trap small organisms like insects, pollen, or even small reptiles. Over decades, the resin hardens through polymerization, a process accelerated by heat and pressure. This rapid preservation is why amber often contains remarkably intact specimens, providing scientists with a window into ancient ecosystems. For instance, Baltic amber, formed around 44 million years ago, has preserved spiders, flies, and even lizard tails in stunning detail. The key takeaway? Amber’s formation is swift, relying on chemical hardening rather than mineral replacement.

Fossil wood, however, follows a far slower path. When a tree dies and is buried under sediment, it begins a journey that can span millions of years. Groundwater rich in minerals like silica or calcite seeps into the wood, gradually replacing its organic cells with stone. This process, called permineralization, requires stable, oxygen-poor environments to prevent decay. The result is a rock-hard replica of the original wood, often retaining its cellular structure. Examples like the petrified forests in Arizona showcase this process, where 225-million-year-old trees have turned into quartz-rich stone. Unlike amber, fossil wood’s transformation is a testament to geological patience, where time and minerals collaborate to create enduring relics.

For enthusiasts or educators, understanding these timelines offers practical insights. Amber can be created artificially in labs by heating and compressing resin, a process that mimics natural conditions over weeks. Fossil wood, however, cannot be replicated on human timescales, making natural specimens invaluable. When identifying these materials, look for amber’s translucence and inclusions versus fossil wood’s weight and grain patterns. Both materials, though formed differently, serve as time capsules, each revealing distinct chapters of Earth’s history.

In the end, the contrast between amber and fossil wood underscores nature’s versatility in preserving the past. One is a quick capture, a snapshot of life frozen in resin; the other is a slow sculpture, carved by minerals over eons. Together, they remind us that time, whether measured in decades or millennia, is the ultimate artist in the story of fossilization.

Poison Ivy Oil on Wood: Duration and Safety Tips

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Preservation Conditions: Anaerobic environments and rapid burial accelerate fossilization

The absence of oxygen is a critical factor in the rapid fossilization of wood. Anaerobic environments, such as the depths of swamps, lakes, or oceanic sediments, deprive microorganisms of the oxygen they need to decompose organic matter. In these settings, wood can evade the typical decay process, which is primarily driven by aerobic bacteria and fungi. For instance, the famous Baltic amber, which often contains remarkably preserved plant material, formed in an anaerobic environment millions of years ago. This preservation is not just about slowing decay—it’s about halting it entirely, allowing the wood to remain intact long enough for mineralization to occur.

Rapid burial plays a complementary role in this process by shielding wood from environmental factors that accelerate decomposition. When wood is quickly buried under layers of sediment, it is protected from sunlight, temperature fluctuations, and scavengers. This isolation creates a stable environment where the chemical processes of fossilization can unfold undisturbed. A practical example is the fossilized forests found in Axel Heiberg Island, Canada, where trees were buried under volcanic ash, preserving them in extraordinary detail. The speed of burial is key—the faster the wood is sequestered, the greater the likelihood of preservation.

To understand the interplay between anaerobic conditions and rapid burial, consider the steps required to replicate these conditions artificially. For experimental purposes, wood can be submerged in anaerobic chambers filled with oxygen-free water or sediment, mimicking the conditions of a swamp or lake bed. Simultaneously, applying pressure to simulate rapid burial can be achieved by layering fine-grained sediments over the wood. Researchers often use this method to study the early stages of fossilization, observing how different minerals infiltrate the wood’s cellular structure. The takeaway is clear: controlling these variables can significantly shorten the time it takes for wood to fossilize, from millennia to potentially centuries under ideal conditions.

While anaerobic environments and rapid burial are powerful accelerants, they are not foolproof. The type of wood, its initial moisture content, and the mineral composition of the surrounding sediment also play crucial roles. For instance, hardwoods like oak or maple, with their denser cell structures, tend to fossilize more readily than softwoods like pine. Practical tips for enthusiasts or researchers include selecting wood with low resin content (to avoid interference with mineralization) and ensuring the burial medium is rich in silica or calcite, minerals commonly involved in permineralization. By combining these factors with anaerobic conditions and rapid burial, the preservation of wood can be optimized, offering a glimpse into the ancient past with remarkable clarity.

Understanding Wood Rot: Factors Influencing Decay Timeline and Prevention Tips

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Wood fossilization usually takes millions of years, often ranging from 10 million to several hundred million years, depending on environmental conditions.

Fossilization requires rapid burial in sediment, low oxygen levels to prevent decay, and the presence of minerals like silica or calcite to replace organic material.

While rare, wood can fossilize more quickly (thousands to tens of thousands of years) in environments with high mineral content, such as volcanic ash or hot springs, through processes like permineralization.

Petrified wood is a specific type of fossil where organic material is completely replaced by minerals, preserving the original structure, while regular fossils may only preserve imprints or partial remains.