The durability of wooden tools used by early hominids is a fascinating yet challenging topic to explore, given the organic nature of wood, which typically decomposes over time. Unlike stone tools, which have been preserved in the archaeological record, wooden artifacts rarely survive due to their susceptibility to decay, making it difficult to determine their lifespan. However, through experimental archaeology and the rare discovery of preserved wooden tools in unique environmental conditions, such as waterlogged or extremely dry sites, researchers have begun to piece together insights into their longevity. Early hominids likely crafted wooden tools for specific tasks, and while these tools may not have lasted as long as their stone counterparts, their utility and adaptability suggest they were replaced or repaired frequently, reflecting a sophisticated understanding of material properties and tool maintenance in these ancient populations.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Material Durability | Wood is less durable than stone; prone to decay, fragmentation, and weathering. |

| Preservation in Archaeological Record | Wooden tools rarely survive due to organic material decomposition; most evidence is indirect (e.g., stone tools used to shape wood). |

| Estimated Lifespan | Days to weeks for perishable tools; longer for hardened or treated wood (e.g., fire-hardened tools may last months). |

| Environmental Factors | Lifespan influenced by climate, soil acidity, and moisture levels; drier, alkaline soils preserve wood better. |

| Tool Function | Simple tools (e.g., digging sticks) may last shorter than complex tools (e.g., spears). |

| Evidence from Modern Analogues | Experimental archaeology suggests wooden tools used intermittently may last weeks to months. |

| Archaeological Examples | Rare finds like the 400,000-year-old wooden spear from Schöningen, Germany, are exceptions, preserved due to unique conditions. |

| Technological Treatment | Fire-hardening or resin treatment can extend lifespan, but evidence in early hominids is limited. |

| Usage Intensity | Frequent use accelerates wear and breakage, reducing overall lifespan. |

| Comparative Lifespan to Stone Tools | Stone tools last significantly longer (years to decades) due to material hardness and durability. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Wood preservation techniques: Early hominids used fire, oils, and resins to extend wooden tool lifespan

- Environmental impact: Climate, moisture, and soil type affected wood durability in early hominid tools

- Tool usage frequency: Heavier use of wooden tools led to faster wear and shorter lifespans

- Material selection: Hominids chose denser woods like oak or acacia for longer-lasting tools

- Archaeological evidence: Charcoal remains and fossilized wood fragments provide clues to tool longevity

Wood preservation techniques: Early hominids used fire, oils, and resins to extend wooden tool lifespan

The durability of wooden tools among early hominids was a critical factor in their survival and technological advancement. Without modern synthetic materials, these ancient toolmakers relied on natural preservation methods to extend the lifespan of their wooden implements. Archaeological evidence suggests that early hominids were remarkably resourceful, employing techniques such as fire treatment, oil application, and resin coating to protect their tools from decay, insects, and environmental wear. These methods not only increased the tools' longevity but also enhanced their functionality, showcasing an early understanding of material science.

Fire was one of the earliest and most effective preservation techniques. By carefully charring the surface of wooden tools, early hominids created a protective layer that resisted moisture and microbial degradation. This process, known as pyrolysis, involved controlled burning at temperatures between 200°C and 300°C for several minutes. The charred layer acted as a barrier, reducing water absorption and preventing fungal growth. For example, wooden spears treated with fire have been found to last up to 5–10 years in humid environments, compared to untreated wood, which deteriorates within 1–2 years. To replicate this technique, ensure the wood is evenly heated and avoid overheating, which can cause brittleness.

Oils and fats were another key preservation method, particularly for tools used in wet or damp conditions. Early hominids likely sourced animal fats or plant oils, such as those from nuts or seeds, and applied them liberally to wooden surfaces. These lipids penetrated the wood fibers, repelling water and maintaining flexibility. A practical tip for modern replication is to heat the oil slightly before application to improve absorption. Tools treated with oils could last 3–5 years, depending on usage and environmental exposure. However, this method required periodic reapplication, as oils degrade over time.

Resins, derived from trees like pine or birch, were prized for their adhesive and waterproofing properties. Early hominids used resins to seal cracks, bind tool components, and create a protective coating. When heated and applied, resins hardened into a durable, water-resistant layer that could extend a tool's lifespan by 2–4 years. Archaeological findings of resin-coated wooden handles suggest that this technique was particularly effective for tools subjected to mechanical stress. To use resin effectively, melt it gently over low heat and apply it in thin, even layers, allowing each coat to dry before adding another.

Comparing these techniques reveals their complementary strengths. Fire treatment provided long-lasting protection but altered the wood's structure, making it less suitable for intricate tools. Oils preserved flexibility but required maintenance, while resins offered both durability and versatility. Early hominids likely combined these methods, tailoring their approach to the tool's function and environment. For instance, a wooden spear might be fire-treated for overall durability, oiled at the handle for grip, and resin-coated at the tip for added strength.

In conclusion, early hominids' wood preservation techniques demonstrate their ingenuity and adaptability. By harnessing fire, oils, and resins, they significantly extended the lifespan of their wooden tools, ensuring their effectiveness in hunting, digging, and other essential tasks. These methods not only highlight their understanding of natural materials but also provide valuable insights for modern woodworkers and archaeologists alike. Experimenting with these ancient techniques can offer both practical benefits and a deeper appreciation for the resourcefulness of our ancestors.

Durability of Wood Pallets: Lifespan and Maintenance Tips

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Environmental impact: Climate, moisture, and soil type affected wood durability in early hominid tools

Wooden tools crafted by early hominids were subject to the relentless forces of their surrounding environment, which dictated their durability and lifespan. Climate, moisture, and soil type emerged as critical factors that could either preserve or hasten the decay of these organic artifacts. In arid regions, such as parts of Africa where early hominids thrived, wooden tools were less prone to rot due to low humidity levels. For instance, wood buried in dry, sandy soils could survive for thousands of years, as evidenced by archaeological finds in the Kalahari Desert. Conversely, tools exposed to tropical climates with high rainfall and humidity deteriorated rapidly, often within decades, due to fungal and bacterial activity.

Moisture, in particular, played a dual role in the fate of wooden tools. While water was essential for shaping and softening wood during tool creation, prolonged exposure to moisture accelerated decay. Early hominids likely selected hardwoods like acacia or ebony, which naturally resist water absorption, to mitigate this risk. However, even these resilient species could succumb to waterlogging in swampy or floodplain environments. Archaeological studies suggest that tools buried in well-drained soils had a significantly longer lifespan compared to those in waterlogged conditions, where anaerobic bacteria thrive and decompose wood more efficiently.

Soil type further influenced wood preservation by affecting pH levels, mineral content, and oxygen availability. Acidic soils, common in forested areas, accelerated wood decay by breaking down cellulose and lignin, the structural components of wood. In contrast, alkaline soils, often found in arid regions, provided a more protective environment by inhibiting microbial activity. For example, wooden tools discovered in the alkaline soils of East Africa’s Rift Valley have been dated to over 1.5 million years old, showcasing the preservative power of certain soil chemistries. Early hominids may have intuitively chosen burial sites with favorable soil conditions, though this remains speculative.

Practical tips for modern archaeologists and enthusiasts seeking to understand or replicate early hominid wooden tools include studying local soil and climate conditions. For experimental archaeology, burying wood samples in various soil types and monitoring their decay over time can yield valuable insights. Additionally, using non-invasive techniques like ground-penetrating radar to locate tools in alkaline or arid environments increases the likelihood of discovering well-preserved artifacts. By understanding these environmental interactions, we can better reconstruct the technological capabilities and adaptations of our ancestors.

In conclusion, the durability of early hominid wooden tools was a delicate balance between material choice and environmental conditions. Climate, moisture, and soil type collectively determined whether these tools would endure for millennia or vanish within a generation. This interplay highlights the ingenuity of early hominids in selecting and preserving their tools, as well as the challenges archaeologists face in uncovering these fragile remnants of our past. By focusing on these environmental factors, we gain a deeper appreciation for the resilience and resourcefulness of our ancestors.

Black Walnut Wood Oxidation: Understanding the Aging Process and Timeline

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Tool usage frequency: Heavier use of wooden tools led to faster wear and shorter lifespans

The durability of wooden tools among early hominids was intimately tied to how frequently they were used. Archaeological evidence suggests that tools subjected to heavier use—such as those employed for repetitive tasks like digging, cutting, or pounding—experienced accelerated wear. For instance, wooden digging sticks used daily to forage for roots would show signs of splintering and abrasion within weeks to months, depending on the hardness of the soil and the force applied. In contrast, tools used sporadically, like those for occasional butchering, might retain their functionality for several months or even years. This relationship between usage frequency and tool lifespan highlights the pragmatic choices early hominids made in tool selection and maintenance.

Consider the mechanics of wear: each strike, scrape, or twist applied to a wooden tool introduces microfractures and material loss. Over time, these cumulative stresses weaken the tool’s structural integrity, leading to breakage or ineffectiveness. Experimental archaeology has demonstrated that even hardwoods, such as oak or acacia, degrade rapidly under constant stress. For example, a wooden spear used repeatedly for hunting large game might last only a few weeks before becoming too brittle or misshapen to be effective. This rapid degradation underscores the need for early hominids to either repair tools frequently or replace them entirely, a behavior supported by the discovery of partially reworked wooden artifacts at sites like Schöningen in Germany.

From a practical standpoint, understanding this wear pattern offers insights into early hominid resource management. Heavier tool use would have necessitated a steady supply of raw materials, either through frequent foraging for suitable wood or the stockpiling of pre-prepared tool blanks. This logistical challenge likely influenced settlement patterns, with groups settling near forests or wooded areas to ensure access to fresh materials. Additionally, the shorter lifespan of heavily used tools may have driven innovation in tool design, such as the addition of stone tips to wooden handles to extend functionality without compromising the entire tool.

A comparative analysis of tool lifespans across hominid species reveals that more advanced groups, such as *Homo heidelbergensis*, may have mitigated wear through strategic use. For instance, alternating between multiple tools for the same task could have distributed wear more evenly, prolonging the collective lifespan of their toolkit. This approach would have required cognitive planning and an understanding of material properties, suggesting a level of sophistication in tool management. Conversely, earlier hominids like *Homo habilis* may have lacked such strategies, leading to more rapid tool depletion and a greater reliance on immediate resource availability.

In conclusion, the frequency of tool use was a critical determinant of wooden tool longevity among early hominids. Heavier use accelerated wear, necessitating frequent repairs or replacements and shaping resource management strategies. By examining this dynamic, we gain a deeper appreciation for the ingenuity and adaptability of our ancestors, who navigated the challenges of tool durability with limited materials and evolving cognitive abilities. This understanding not only enriches our knowledge of hominid behavior but also underscores the importance of tool use in the development of human culture and technology.

Moisture and Wood Rot: Understanding the Timeline for Decay

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Material selection: Hominids chose denser woods like oak or acacia for longer-lasting tools

Early hominids, in their quest for survival, demonstrated a keen understanding of material properties long before the advent of modern science. Their choice of denser woods like oak and acacia for crafting tools was not arbitrary but a deliberate decision rooted in practicality. These woods, with their higher density, offered superior durability compared to softer alternatives. For instance, oak, with a density of approximately 700 kg/m³, and acacia, at around 800 kg/m³, provided the necessary strength to withstand repeated use in tasks such as digging, cutting, and pounding. This selection ensured that tools lasted longer, reducing the frequency of replacement and conserving valuable time and energy.

The analytical perspective reveals that the preference for denser woods was a strategic adaptation to environmental challenges. Softer woods, like pine or balsa, though easier to work with, lacked the resilience required for prolonged use. A tool made from balsa wood, with a density of just 140 kg/m³, would wear out significantly faster under the same conditions as one made from oak or acacia. This disparity in durability highlights the hominids’ ability to evaluate and prioritize material properties based on their needs. By opting for denser woods, they maximized the lifespan of their tools, a critical factor in their resource-limited existence.

From an instructive standpoint, replicating early hominid tool-making practices can offer valuable insights into sustainable material selection. For modern enthusiasts or educators, choosing wood with a density above 600 kg/m³, such as maple or beech, can serve as a practical alternative if oak or acacia is unavailable. When crafting tools, focus on minimizing exposure to moisture, as even dense woods can degrade over time when wet. Applying natural preservatives like linseed oil can further enhance durability. These steps, inspired by hominid ingenuity, demonstrate how thoughtful material selection and maintenance can extend the life of wooden tools.

A comparative analysis underscores the evolutionary advantage conferred by this material choice. While stone tools offered unmatched hardness, they were labor-intensive to produce and not always readily available. Wooden tools, particularly those made from dense woods, provided a middle ground—easier to craft than stone yet more durable than softer materials. This balance allowed hominids to allocate resources efficiently, focusing on tasks like hunting and gathering rather than constant tool repair. The longevity of oak and acacia tools, estimated to last several months to a year with regular use, exemplifies this pragmatic approach.

Descriptively, envision a hominid carefully selecting a sturdy acacia branch, its dense grain visible even to the untrained eye. With deliberate strikes, they shape it into a digging stick, the wood’s resilience evident in each blow. This tool, unlike its softer counterparts, retains its form through seasons of use, its surface bearing the patina of countless tasks. Such a scene illustrates not just the physical act of tool-making but the deeper cognitive process of material evaluation—a testament to the ingenuity that defined early hominid survival strategies.

Teak Oil Drying Time: How Long Does It Take on Wood?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Archaeological evidence: Charcoal remains and fossilized wood fragments provide clues to tool longevity

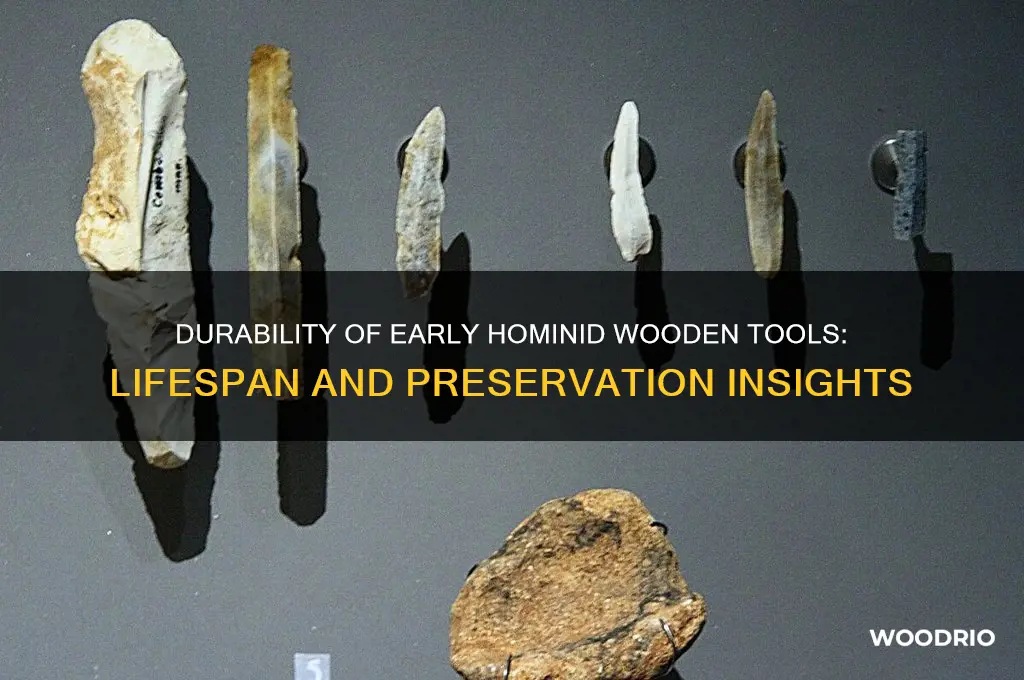

Wooden tools, unlike their stone counterparts, rarely survive the ravages of time. Organic materials decompose, leaving archaeologists with a fragmented puzzle. Yet, charcoal remains and fossilized wood fragments offer tantalizing clues about the longevity of early hominid wooden tools. These remnants, often found in ancient hearths or buried under layers of sediment, provide a window into the past, revealing not just the presence of wood but also its use and durability.

Charcoal, formed when wood is burned in low-oxygen conditions, preserves the cellular structure of the original material. By analyzing charcoal remains, researchers can identify the type of wood used, its density, and even the season it was cut. For instance, studies of charcoal from early hominid sites in Africa have shown that hardwoods like acacia and olive were favored for toolmaking due to their strength and resistance to decay. These findings suggest that early hominids selected materials with inherent durability, potentially extending the lifespan of their wooden tools.

Fossilized wood fragments, though rarer, provide even more direct evidence of tool longevity. Fossilization occurs when wood is buried in mineral-rich sediments, replacing organic material with minerals over thousands of years. Such fragments often retain tool marks, such as notches or wear patterns, indicating prolonged use. A notable example is a fossilized wooden spear point discovered at the Schöningen site in Germany, dated to around 300,000 years ago. Its preservation suggests that, under ideal conditions, wooden tools could last for millennia, though such instances are exceptional.

To estimate tool longevity from these remains, archaeologists employ a combination of techniques. Radiocarbon dating of charcoal provides a timeline, while microscopic analysis of fossilized wood reveals signs of wear and repair. For instance, repeated sharpening or reshaping of a tool indicates extended use, possibly spanning years or even generations. However, these methods have limitations. Charcoal can only date the burning event, not the original tool’s creation, and fossilization is a rare process. Despite these challenges, the evidence points to a surprising resilience in wooden tools, particularly when crafted from durable materials and used in controlled environments.

Practical takeaways from this evidence include the importance of material selection and environmental context. Early hominids likely chose hardwoods for their tools, knowing these materials could withstand repeated use. Modern experimental archaeology supports this, showing that well-crafted wooden tools can last for years, even decades, under moderate use. For enthusiasts recreating ancient tools, selecting dense, rot-resistant woods like oak or hickory and storing them in dry conditions can mimic the longevity observed in archaeological remains. While wooden tools may not endure as long as stone, their lifespan was far from fleeting, reflecting the ingenuity and resourcefulness of our ancestors.

CCA Treated Wood Durability: Longevity and Factors Affecting Lifespan

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

In ideal preservation conditions, such as waterlogged or anaerobic environments, wooden tools made by early hominids could last for tens of thousands to hundreds of thousands of years. Examples like the 400,000-year-old wooden spear from Schöningen, Germany, demonstrate their durability under such circumstances.

Most wooden tools do not survive because wood is highly biodegradable. Exposure to oxygen, moisture, microorganisms, and environmental factors causes it to decay rapidly, often within decades or centuries, unless preserved in exceptional conditions.

Yes, techniques like radiocarbon dating, dendrochronology, and microscopic analysis can provide insights into the age and durability of wooden tools. However, these methods rely on the rare instances where tools are preserved, limiting their applicability.

Early hominids likely used natural resins, fire-hardening, and careful selection of dense woods to increase tool durability. They also probably replaced tools frequently due to their limited lifespan, as evidenced by the abundance of stone tools in the archaeological record compared to wood.