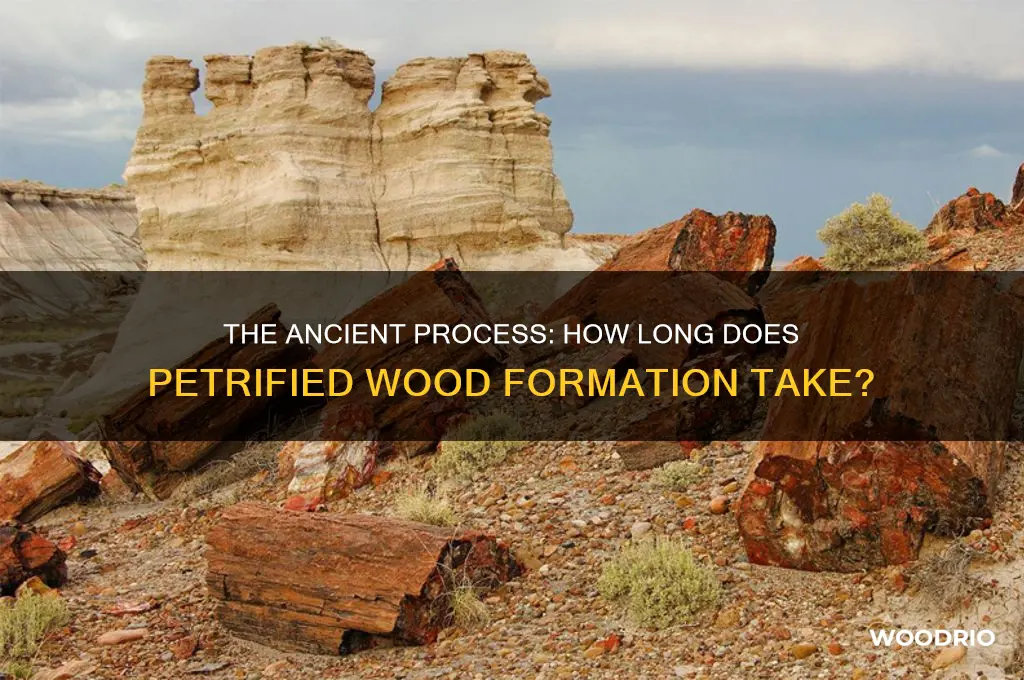

Petrified wood, a fascinating natural wonder, is the result of an incredibly slow process that transforms ancient trees into stone over millions of years. This remarkable phenomenon begins when a tree is buried under sediment, such as volcanic ash, mud, or sand, cutting off oxygen and preventing decay. Over time, groundwater rich in minerals like silica seeps into the wood, gradually replacing the organic material cell by cell with minerals, most commonly quartz. This process, known as permineralization, can take anywhere from 5,000 to 20 million years, depending on environmental conditions such as the mineral content of the water, temperature, and pressure. The end result is a fossilized log that retains the original structure of the wood, often with stunningly detailed patterns and vibrant colors, offering a glimpse into Earth’s prehistoric past.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Formation Time | Typically millions of years (ranging from 10,000 to 100 million years) |

| Key Process | Permineralization (replacement of organic material with minerals like silica) |

| Required Conditions | - Burial under sediment or volcanic ash - Presence of mineral-rich water - Lack of oxygen (anaerobic environment) |

| Minerals Involved | Primarily silica (quartz), but also calcite, pyrite, and others |

| Preservation Level | Detailed cellular structures and even original wood grain can be preserved |

| Environmental Factors | Rate depends on temperature, pH, and mineral concentration in water |

| Notable Examples | Petrified Forest National Park (Arizona, USA) – formed ~225 million years ago |

| Rarity | Rare due to specific conditions required for preservation |

| Scientific Significance | Provides insights into ancient ecosystems and geological history |

Explore related products

$64.11 $77.99

What You'll Learn

- Mineralization Process: Silica-rich water seeps into wood, replacing organic material with minerals over time

- Environmental Conditions: Requires buried wood in sediment with high mineral content and low oxygen

- Timeframe Variability: Formation can take thousands to millions of years, depending on conditions

- Fossilization Stages: Begins with decay prevention, followed by mineral infiltration and hardening

- Accelerating Factors: High pressure, temperature, and mineral concentration can speed up petrification

Mineralization Process: Silica-rich water seeps into wood, replacing organic material with minerals over time

The mineralization process that transforms wood into petrified wood is a slow, intricate dance between organic matter and inorganic minerals. It begins when silica-rich water, often from volcanic ash or groundwater, seeps into the cellular structure of buried wood. Over millennia, this water acts as a molecular architect, systematically replacing the wood’s organic components with minerals like quartz, calcite, or pyrite. This isn’t a haphazard process; it’s a precise, atom-by-atom substitution that preserves the wood’s original texture and structure, creating a fossilized replica.

To understand the timeline, consider the conditions required: the wood must be buried in sediment, shielded from oxygen and decay, with a consistent supply of mineral-laden water. Under ideal conditions—such as those found in ancient riverbeds or volcanic ash layers—this process can take millions of years. For example, the petrified wood found in Arizona’s Petrified Forest National Park dates back to the Triassic Period, over 225 million years ago. However, smaller samples or those in highly mineralized environments may form in as little as 10,000 to 100,000 years. The key variable is the rate of silica infiltration, which depends on factors like temperature, pressure, and mineral concentration in the surrounding environment.

Practical observation reveals that petrification isn’t uniform. Some sections of wood may mineralize faster than others, depending on their exposure to silica-rich fluids. For instance, the outer layers of a tree trunk might petrify first, while the inner core remains softer for longer. This uneven process can create stunning visual contrasts, with different minerals forming distinct colors—quartz yielding whites and grays, iron oxides producing reds and yellows, and manganese contributing to blacks and blues.

If you’re attempting to replicate this process artificially, such as in lapidary or experimental geology, accelerate the timeline by using pressurized, silica-saturated solutions at elevated temperatures. Laboratory experiments have shown that petrification-like processes can be induced in months to years under controlled conditions. However, these artificial specimens lack the complexity and durability of naturally formed petrified wood, which has endured geological forces for eons.

In essence, the mineralization process is a testament to nature’s patience and precision. Whether occurring over millennia in the earth’s crust or expedited in a lab, it transforms fragile wood into enduring stone, preserving a snapshot of ancient ecosystems. For collectors, scientists, or enthusiasts, understanding this process deepens appreciation for the intricate interplay of time, chemistry, and geology that creates petrified wood.

Mastering Wood Chip Soaking: Optimal Time for Perfect Smoking Results

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Environmental Conditions: Requires buried wood in sediment with high mineral content and low oxygen

Buried wood doesn’t petrify by accident. It demands a specific set of environmental conditions, a geological recipe that transforms organic matter into stone. The first ingredient is burial in sediment, a protective blanket that shields the wood from decay and exposure. This sediment must be rich in minerals, particularly silica, which acts as the building block for the petrification process. Without this mineral-laden environment, the wood would simply rot away, leaving no trace of its existence.

Low oxygen levels are equally critical. Oxygen fuels decomposition, the very process petrification seeks to halt. In an oxygen-poor environment, such as deep sediment or underwater, bacteria and fungi struggle to survive, slowing the breakdown of the wood. This creates a window of opportunity for minerals to infiltrate the wood’s cellular structure, replacing organic material with stone. Think of it as a race against time: the sediment must bury the wood quickly enough to starve out decomposers, preserving the wood’s structure for mineralization.

Consider the example of the Petrified Forest National Park in Arizona, where ancient trees were buried under volcanic ash and mud. The ash, rich in silica, provided the necessary minerals, while the dense sediment layers deprived the wood of oxygen. Over millions of years, groundwater seeped through the sediment, carrying dissolved silica that slowly crystallized within the wood’s cells. This process, known as permineralization, turned the trees into quartz-rich stone, preserving even the finest details of their structure.

To replicate these conditions artificially, one might bury wood in a mixture of silica-rich sand and clay, ensuring it’s completely covered to minimize oxygen exposure. The burial site should be in a stable, undisturbed area, such as the bottom of a dry lake bed or a deep trench. Over time—likely thousands of years—groundwater or mineral-rich solutions must permeate the sediment, allowing minerals to replace the wood’s organic matter. While this process is far slower than natural petrification, it demonstrates the critical interplay of sediment, minerals, and oxygen deprivation.

The takeaway is clear: petrification isn’t just about time; it’s about the right environment. Without burial in mineral-rich sediment and low-oxygen conditions, wood stands no chance of transforming into stone. These conditions aren’t common, which is why petrified wood is both rare and scientifically valuable. It’s a testament to the precision of geological processes, a reminder that even the most mundane materials can become extraordinary under the right circumstances.

Wood Putty Shelf Life: How Long Does It Last in the Jar?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Timeframe Variability: Formation can take thousands to millions of years, depending on conditions

Petrified wood formation is a geological process that defies simple timelines. While the basic recipe—buried wood, mineral-rich water, and time—remains constant, the clock ticks at wildly different rates depending on environmental conditions. This variability spans from thousands to millions of years, making each piece of petrified wood a unique record of its specific journey from organic matter to mineralized fossil.

Understanding this timeframe variability is crucial for appreciating the rarity and value of petrified wood. It also highlights the delicate interplay between geology, chemistry, and time that shapes our natural world.

The Accelerators: When Time Moves Faster

Certain conditions can expedite the petrification process. High temperatures, for example, increase the rate of chemical reactions, allowing minerals to infiltrate wood cells more rapidly. This is often observed in volcanic environments where hot, mineral-laden waters permeate buried wood. Similarly, highly concentrated mineral solutions, such as those found in geothermal springs, can accelerate the replacement of organic material with silica, calcite, or other minerals. In these scenarios, petrification can occur within a few thousand years, a blink of an eye in geological terms.

The Slow Burn: Patience Rewarded

Conversely, cooler, less reactive environments slow the petrification process to a glacial pace. Shallow burial in sedimentary rock, for instance, exposes wood to less intense mineralization. The slow seepage of groundwater through porous rock allows minerals to gradually replace cell walls over millions of years. This protracted process often results in exceptionally detailed preservation, with individual cell structures and even growth rings visible in the fossilized wood.

The Takeaway: A Spectrum of Time

The formation of petrified wood is not a singular event but a spectrum of possibilities. From the rapid mineralization in volcanic settings to the slow, meticulous process in sedimentary environments, the timeframe is dictated by the unique interplay of temperature, mineral availability, and geological context. This variability underscores the remarkable adaptability of nature and the enduring legacy of ancient life preserved in stone.

Composting Wood Chips: Understanding the Timeframe for Natural Breakdown

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$6.99

Fossilization Stages: Begins with decay prevention, followed by mineral infiltration and hardening

Petrified wood, a captivating transformation of ancient organic matter into stone, doesn't happen overnight. It's a meticulous process spanning millennia, a testament to nature's patience and the intricate dance of geology and chemistry.

Understanding this process requires dissecting the key stages: decay prevention, mineral infiltration, and hardening.

The Race Against Time: Preventing Decay

Imagine a fallen tree, its life force extinguished. Left unchecked, bacteria and fungi would swiftly decompose its cellular structure, reducing it to dust. For petrification to occur, this race against decay must be won. Rapid burial is crucial. Sediment, ash, or volcanic material act as shields, depriving decomposers of oxygen and slowing their destructive work. This initial stage, though seemingly passive, is a critical battle for preservation, determining whether the wood becomes a fossil or simply fades into the earth.

Think of it as placing a time capsule in the ground – the quicker it's sealed, the better its contents are preserved.

The Mineral Invasion: A Silent Transformation

Buried and shielded from decay, the wood enters a new phase. Groundwater, rich in dissolved minerals like silica, calcium, and iron, seeps through the buried wood. This isn't a violent invasion, but a slow, meticulous infiltration. Over centuries, these minerals replace the wood's organic cells, molecule by molecule. Cell walls, once composed of cellulose, are gradually transformed into stone, retaining the wood's original structure in astonishing detail. This stage is akin to an artist meticulously painting over a canvas, stroke by stroke, until the original image is completely transformed.

Hardening into Eternity: The Final Act

As mineral infiltration continues, the wood becomes increasingly dense and hard. The once-organic material, now a composite of minerals, undergoes a final transformation. Pressure from overlying sediment and geological processes further compact the minerals, solidifying the wood into a durable, stone-like substance. This hardening stage is the culmination of millions of years of patient geological work, resulting in a fossil that can withstand the test of time, a silent testament to a bygone era.

Imagine a potter firing clay – the heat hardens the material, transforming it from a malleable substance into a permanent, unyielding form.

A Process Measured in Millennia

The entire petrification process is a marathon, not a sprint. While the exact duration varies depending on factors like mineral composition, temperature, and pressure, it typically takes millions of years. Some estimates suggest it can take anywhere from 10 million to several hundred million years for complete petrification. This staggering timescale highlights the immense patience required for nature to create these captivating fossils.

A Window to the Past

Petrified wood, born from the meticulous stages of decay prevention, mineral infiltration, and hardening, offers a unique glimpse into Earth's history. Each fossilized log is a time capsule, preserving the structure and sometimes even the cellular details of ancient trees. By understanding the stages of fossilization, we gain a deeper appreciation for the intricate processes that shape our planet and the remarkable relics they leave behind.

Durability of Wood-Cored Fiberglass Hulls: Lifespan and Maintenance Tips

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Accelerating Factors: High pressure, temperature, and mineral concentration can speed up petrification

Petrified wood typically takes millions of years to form under natural conditions, but certain factors can significantly accelerate this process. High pressure, elevated temperatures, and concentrated mineral solutions act as catalysts, compressing the timeline from millennia to potentially centuries or even decades in controlled environments. Understanding these accelerating factors not only sheds light on the geological processes behind petrification but also opens doors to replicating the phenomenon artificially for scientific, artistic, or commercial purposes.

Consider the role of pressure, a force that drives minerals deep into the cellular structure of wood. In nature, this occurs as sediment layers accumulate over buried organic material, gradually increasing the pressure over time. However, in laboratory settings, applying controlled pressure of 2,000 to 5,000 psi (pounds per square inch) can mimic this effect, reducing the petrification timeline dramatically. For instance, experiments have shown that wood subjected to such pressures, combined with mineral-rich solutions, can exhibit early stages of petrification within just a few years. This method is particularly useful for researchers studying fossilization processes or artists creating petrified wood sculptures.

Temperature plays an equally critical role, as heat accelerates the chemical reactions involved in petrification. In geothermal areas, where temperatures naturally range from 150°C to 200°C (302°F to 392°F), petrification can occur at a faster rate due to the increased mobility of mineral ions. Artificially, this can be replicated using autoclaves, which subject wood to high temperatures and pressures simultaneously. For optimal results, maintaining a temperature of 175°C (347°F) for 48 to 72 hours, combined with a silica-rich solution, has been shown to initiate petrification within months rather than centuries. This technique is invaluable for industries producing petrified wood for decorative or structural purposes.

Mineral concentration is another key factor, as higher levels of dissolved minerals like silica, calcite, and pyrite expedite the replacement of organic material. In natural settings, this often occurs in mineral-rich groundwater, but artificially, solutions with mineral concentrations of 20% to 30% by weight can be used to saturate wood samples. For example, soaking wood in a silica gel solution with a pH of 8.5 to 9.0 accelerates the silicification process, turning wood into stone-like material within 5 to 10 years. This approach is particularly useful for educational institutions demonstrating petrification in real-time or for hobbyists creating petrified wood specimens.

While these accelerating factors offer exciting possibilities, they also come with challenges. High pressure and temperature require specialized equipment, and maintaining precise conditions can be costly. Additionally, artificially petrified wood may lack the intricate details and natural beauty of its million-year-old counterparts. However, for those seeking to understand or replicate petrification, these methods provide a practical and efficient pathway. By harnessing the power of pressure, temperature, and mineral concentration, the ancient process of petrification can be brought into the present, offering both scientific insights and creative opportunities.

How Long Does a Cord of Wood Last Before Decay?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Petrified wood formation typically takes millions of years, often ranging from 5 to 50 million years, depending on environmental conditions.

The time required depends on factors like the presence of silica-rich water, temperature, pressure, and the type of wood. Faster petrification occurs in environments with abundant minerals and stable conditions.

While rare, some accelerated petrification processes can occur in as little as tens of thousands of years under ideal conditions, such as in hot springs or volcanic environments.

Petrification involves the slow replacement of organic material with minerals, a process that requires the gradual infiltration of mineral-rich water and the dissolution of wood cells, which is naturally slow.

Yes, scientists and artisans can replicate petrification in labs or workshops using high-pressure, mineral-rich solutions, reducing the time to weeks or months, though this is not natural petrification.