Baking wood to make charcoal is a traditional process that involves heating wood in a low-oxygen environment to remove moisture and volatile compounds, leaving behind a carbon-rich material. The duration of this process, known as pyrolysis, can vary significantly depending on factors such as the type of wood, the size of the wood pieces, and the temperature used. Typically, baking wood to produce charcoal takes anywhere from 3 to 8 hours, with hardwoods like oak or maple requiring longer times compared to softer woods like pine. Maintaining a consistent temperature between 350°C to 500°C (662°F to 932°F) is crucial to ensure complete carbonization without combustion. Proper ventilation and monitoring are essential to achieve high-quality charcoal while minimizing the risk of fire or incomplete pyrolysis.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Temperature Range | 350°C to 500°C (662°F to 932°F) |

| Optimal Temperature | 400°C to 450°C (752°F to 842°F) |

| Duration for Small Pieces | 3 to 4 hours |

| Duration for Large Logs | 5 to 7 hours or longer |

| Oxygen Control | Limited oxygen (pyrolysis process) |

| Moisture Content | Wood should be dry (below 20% moisture) |

| Type of Wood | Hardwoods (e.g., oak, maple) preferred for higher quality charcoal |

| Cooling Time | 1 to 2 hours after baking |

| Yield | Approximately 25-30% of original wood weight |

| Process Method | Traditional pit method or kiln baking |

| Environmental Impact | Releases volatile gases; proper ventilation required |

| Carbonization Stage | Wood turns into charcoal after volatile compounds are driven off |

| Final Product Color | Black or dark gray |

| Energy Efficiency | Requires sustained heat source (e.g., wood fire or gas) |

| Safety Precautions | Avoid open flames; use protective gear |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Optimal Baking Temperature: Ideal heat range for wood to charcoal conversion without combustion

- Baking Duration: Time required for complete carbonization based on wood type

- Wood Preparation: Sizing and drying wood before baking for efficient charcoal production

- Oxygen Control: Managing airflow to prevent burning while ensuring thorough carbonization

- Cooling Process: Safely cooling charcoal post-bake to stabilize and prevent re-ignition

Optimal Baking Temperature: Ideal heat range for wood to charcoal conversion without combustion

The transformation of wood into charcoal is a delicate dance with heat, where temperature control is paramount. Too low, and the process stalls; too high, and combustion takes over, reducing your wood to ash. The ideal temperature range for this conversion falls between 250°C to 400°C (482°F to 752°F). At these temperatures, the wood undergoes pyrolysis—a thermochemical decomposition that drives off volatile compounds, leaving behind the carbon-rich structure of charcoal. This range is a Goldilocks zone: hot enough to facilitate the chemical changes but cool enough to prevent ignition.

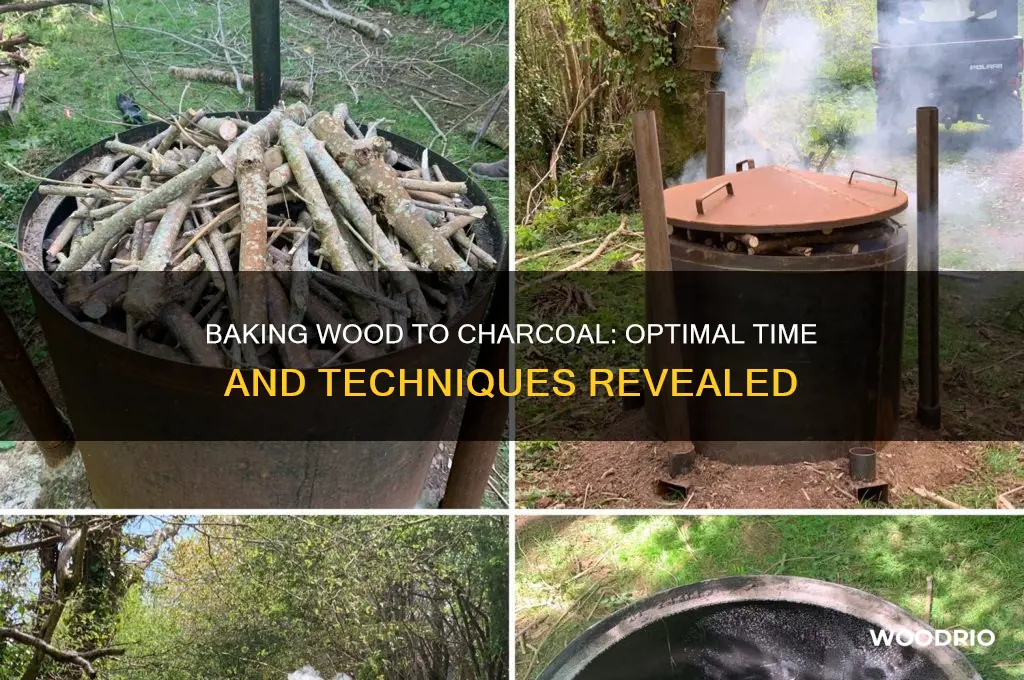

Achieving this temperature range requires precision and monitoring. For small-scale charcoal production, such as in a kiln or metal drum, gradual heating is key. Start by bringing the wood to 150°C (302°F) over 1-2 hours, then steadily increase the heat to the optimal range. This slow ramp-up ensures even drying and prevents localized hot spots that could lead to combustion. Use a thermometer to monitor the internal temperature, adjusting the heat source as needed. For larger operations, automated systems with temperature sensors can maintain consistency, but the principle remains the same: control is critical.

Comparing this process to other forms of wood treatment highlights its uniqueness. For instance, smoking wood for flavor typically operates at temperatures below 100°C (212°F), while combustion for energy generation exceeds 600°C (1112°F). Charcoal production occupies a middle ground, demanding a balance between heat intensity and duration. Unlike combustion, which seeks to release energy, pyrolysis aims to preserve carbon, making temperature control not just a technical detail but the core of the process.

Practical tips can further refine your approach. Ensure the wood is dry before baking, as moisture can interfere with heat distribution and prolong the process. Hardwoods like oak or maple are ideal due to their higher carbon content, but softwoods can also be used with slightly shorter baking times. Once the optimal temperature is reached, maintain it for 3-6 hours, depending on the wood density and desired charcoal quality. Finally, cool the charcoal slowly to prevent cracking, which can compromise its structural integrity.

In conclusion, mastering the optimal baking temperature for wood-to-charcoal conversion is a blend of science and art. By staying within the 250°C to 400°C range, monitoring heat meticulously, and applying practical techniques, you can transform wood into high-quality charcoal efficiently and safely. This precision ensures the end product retains its energy density and versatility, whether for grilling, metallurgy, or soil amendment.

Best Timing for Splitting Wood: Tips for Optimal Results

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Baking Duration: Time required for complete carbonization based on wood type

The time required to bake wood into charcoal varies significantly based on the type of wood, with denser hardwoods like oak or hickory taking longer to carbonize than softer woods like pine or poplar. Hardwoods, rich in lignin and cellulose, typically require 3 to 5 hours at temperatures between 700°F and 1,000°F (371°C to 538°C) for complete carbonization. In contrast, softwoods, which have lower density and resin content, can achieve full carbonization in 2 to 4 hours under the same conditions. This disparity underscores the importance of matching baking duration to wood type to ensure efficient charcoal production.

For those seeking precision, a step-by-step approach can optimize results. Begin by preheating your kiln or retort to 500°F (260°C) to dry the wood, a process that takes 1 to 2 hours. Gradually increase the temperature to 700°F (371°C) and maintain it for the duration specified for your wood type. For hardwoods, extend this phase to 4 hours, while softwoods require only 2 to 3 hours. Finally, allow the charcoal to cool slowly over 1 to 2 hours to prevent cracking. Monitoring temperature and time with a digital thermometer ensures consistency and avoids under or over-carbonization.

A comparative analysis reveals that while hardwoods demand more time, they yield denser, longer-burning charcoal, making them ideal for grilling or industrial use. Softwoods, though quicker to carbonize, produce lighter charcoal with higher ash content, better suited for kindling or short-duration fires. For example, oak takes approximately 5 hours to transform into high-quality charcoal, whereas pine completes the process in 3 hours but results in a less durable product. This trade-off highlights the need to align wood selection with intended charcoal use.

Practical tips can further enhance efficiency. For small-scale production, use a metal drum or clay kiln to control heat distribution. Ensure proper ventilation to maintain consistent airflow, critical for even carbonization. For hardwoods, consider splitting logs into smaller pieces to reduce baking time without compromising quality. Conversely, softwoods benefit from being left in larger chunks to minimize resin loss. Always prioritize safety by wearing heat-resistant gloves and working in a well-ventilated area to avoid inhaling harmful fumes.

In conclusion, mastering the baking duration for wood carbonization hinges on understanding wood type and applying tailored techniques. Hardwoods require patience but reward with superior charcoal, while softwoods offer a quicker but less robust alternative. By combining precise temperature control, appropriate timing, and practical adjustments, anyone can produce high-quality charcoal suited to their needs. This knowledge not only optimizes the process but also ensures sustainable and efficient use of resources.

Wood Putty Drying Time: How Long Does It Take to Harden?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Wood Preparation: Sizing and drying wood before baking for efficient charcoal production

The size of your wood pieces directly impacts the efficiency of charcoal production. Larger chunks take longer to heat through, leading to uneven carbonization and potentially leaving behind uncharred wood. Conversely, excessively small pieces can burn away too quickly, reducing yield. Aim for a consistent size range, typically 2-4 inches in diameter, to ensure even heating and maximize charcoal output. This size allows for sufficient airflow within the pile while providing enough mass for efficient carbonization.

Think of it like roasting marshmallows: too big, and the outside burns while the inside remains cold; too small, and they disappear in a puff of smoke.

Drying wood is crucial before baking it into charcoal. Moisture acts as a barrier, absorbing heat that could be used for carbonization. Aim for a moisture content below 20% for optimal results. Air-drying is the most common method, requiring stacking wood in a well-ventilated area for several months. For faster drying, consider using a kiln, but be mindful of the energy costs involved. Remember, drier wood means less smoke, faster carbonization, and ultimately, higher quality charcoal.

Imagine trying to roast a wet marshmallow – it steams and sputters instead of achieving that golden brown perfection.

While sizing and drying are essential, don't overlook the importance of wood species. Different woods have varying densities and resin contents, affecting burning characteristics and charcoal quality. Hardwoods like oak and hickory are prized for their high density and long burn times, making them ideal for charcoal production. Softer woods like pine, while faster to carbonize, produce charcoal with a lower heat output and more ash. Choose your wood wisely, considering both availability and desired charcoal properties.

Just as different grapes yield distinct wines, different woods impart unique characteristics to the final charcoal product.

Is Old Pressure-Treated Wood Toxic? Pre-2003 Safety Concerns

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Oxygen Control: Managing airflow to prevent burning while ensuring thorough carbonization

The delicate dance of oxygen control is the linchpin of successful charcoal production. Too much air, and your wood burns to ash; too little, and it smolders incompletely. The sweet spot lies in a carefully managed airflow that facilitates pyrolysis—the thermal decomposition of wood in the absence of oxygen—while preventing combustion. This process requires a nuanced understanding of how oxygen interacts with wood at various stages of carbonization.

To achieve this balance, start by arranging your wood in a tightly packed pile or retort, ensuring minimal gaps for air infiltration. As the wood heats, gradually restrict airflow by covering the pile with a layer of soil, metal, or a purpose-built kiln lid. This initial restriction limits oxygen availability, forcing the wood to undergo pyrolysis rather than burning. However, complete airtightness is counterproductive; a small, controlled air intake is necessary to sustain the reaction and remove volatile gases released during carbonization.

The critical phase occurs when the wood reaches temperatures between 250°C and 400°C (482°F to 752°F). At this stage, volatile compounds like water, methane, and tar vaporize, leaving behind fixed carbon. Here, precise oxygen management is paramount. Introduce a minimal, regulated airflow—often through small vents or chimneys—to expel these gases without introducing enough oxygen to ignite them. This step is both art and science, requiring vigilance and adjustments based on visible cues like smoke color and intensity.

For example, in traditional earth kiln methods, operators monitor the smoke’s hue: a thin, blue smoke indicates optimal pyrolysis, while thick, dark smoke suggests insufficient airflow, and a sudden flare-up signals excess oxygen. Modern kilns often incorporate thermocouples and adjustable dampers to fine-tune airflow, ensuring a consistent temperature gradient. Regardless of the method, the goal remains the same: maintain a low-oxygen environment that allows carbonization to proceed without combustion.

In practice, this means starting with a higher airflow during the initial drying phase, then progressively reducing it as the wood transitions from drying to pyrolysis. The final stage, carbonization, demands the most stringent oxygen control. Here, airflow should be minimal but sufficient to remove residual gases, typically maintained at a rate of 1-2 liters per minute per kilogram of wood. This precision ensures the wood transforms into high-quality charcoal, rich in carbon and free from impurities.

Mastering oxygen control is not just about preventing fire; it’s about optimizing the transformation of wood into charcoal. By understanding the interplay between airflow, temperature, and pyrolysis, producers can achieve efficient, consistent results. Whether using traditional methods or advanced kilns, the principle remains: manage oxygen meticulously to turn wood into a valuable, energy-dense resource.

Treated Wood Deck Care: Optimal Waiting Time for Treatment

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Cooling Process: Safely cooling charcoal post-bake to stabilize and prevent re-ignition

The cooling phase is a critical step in charcoal production, often overlooked yet essential for safety and quality. After the wood has been baked in a low-oxygen environment to drive off volatile compounds, the resulting charcoal is still extremely hot and reactive. Rapid or improper cooling can lead to re-ignition, compromising the entire batch. To stabilize the charcoal, a controlled cooling process is necessary, typically taking 6 to 12 hours, depending on the scale of production and the method used. This gradual reduction in temperature ensures the charcoal’s structural integrity and prevents spontaneous combustion.

One effective method for cooling charcoal is the passive cooling approach, where the kiln or retort is simply left to cool naturally after the baking process. This method is ideal for small-scale operations and requires minimal intervention. However, it demands careful monitoring to ensure the temperature drops uniformly. For larger operations, active cooling techniques, such as introducing controlled airflow or using water mist, can expedite the process. Water cooling, while faster, must be applied sparingly to avoid cracking or damaging the charcoal. A common rule of thumb is to use 1 liter of water per 10 kilograms of charcoal, applied in a fine mist to prevent thermal shock.

Comparing these methods highlights the trade-offs between time, resources, and safety. Passive cooling is cost-effective and low-risk but time-consuming, while active cooling saves time but requires precision to avoid compromising the charcoal’s quality. For instance, excessive water can introduce moisture, which later affects combustion efficiency. Conversely, uneven airflow can leave hotspots that increase the risk of re-ignition. The choice of method should align with the scale of production and available resources, emphasizing safety and consistency.

A practical tip for both methods is to insulate the cooling area to retain heat initially, allowing for a gradual temperature drop. This can be achieved by covering the kiln with insulating materials like clay, sand, or fire blankets. Once the charcoal’s surface temperature drops below 50°C (122°F), it is safe to handle and store. Always use heat-resistant gloves and tools during this process, as residual heat can cause burns. Proper cooling not only stabilizes the charcoal but also enhances its durability, ensuring it remains a reliable fuel source for extended periods.

In conclusion, the cooling process is as vital as the baking phase in charcoal production. Whether opting for passive or active cooling, the goal is to achieve a stable, non-reactive product without sacrificing quality. By understanding the nuances of each method and implementing practical precautions, producers can minimize risks and maximize efficiency, turning raw wood into high-quality charcoal with confidence.

Durability of Wood Arrows: Lifespan, Care, and Longevity Tips

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The process usually takes 3 to 5 hours, depending on the type of wood, kiln efficiency, and desired charcoal quality.

No, a regular oven is not suitable for making charcoal. The process requires high temperatures (700–900°C or 1,300–1,650°F) and controlled oxygen levels, typically achieved in a kiln or pit.

Yes, denser hardwoods like oak or maple take longer to carbonize compared to softer woods like pine, which may bake faster but produce lower-quality charcoal.

Yes, baking wood in a sealed or controlled environment (like a kiln) is essential to limit oxygen, allowing the wood to carbonize into charcoal instead of burning completely.

The wood is fully carbonized when it turns into a lightweight, black, porous material. You can also check for a metallic sound when tapping it, indicating it’s ready.

![[220 Sheets] Full Sheet Pan 16 x 24 Inch Parchment Paper Baking Sheets by Baker’s Signature | Precut Silicone Coated & Unbleached – Will Not Curl or Burn – Non-Toxic & Comes in Convenient Packaging](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/91QWlNGeiNL._AC_UL320_.jpg)