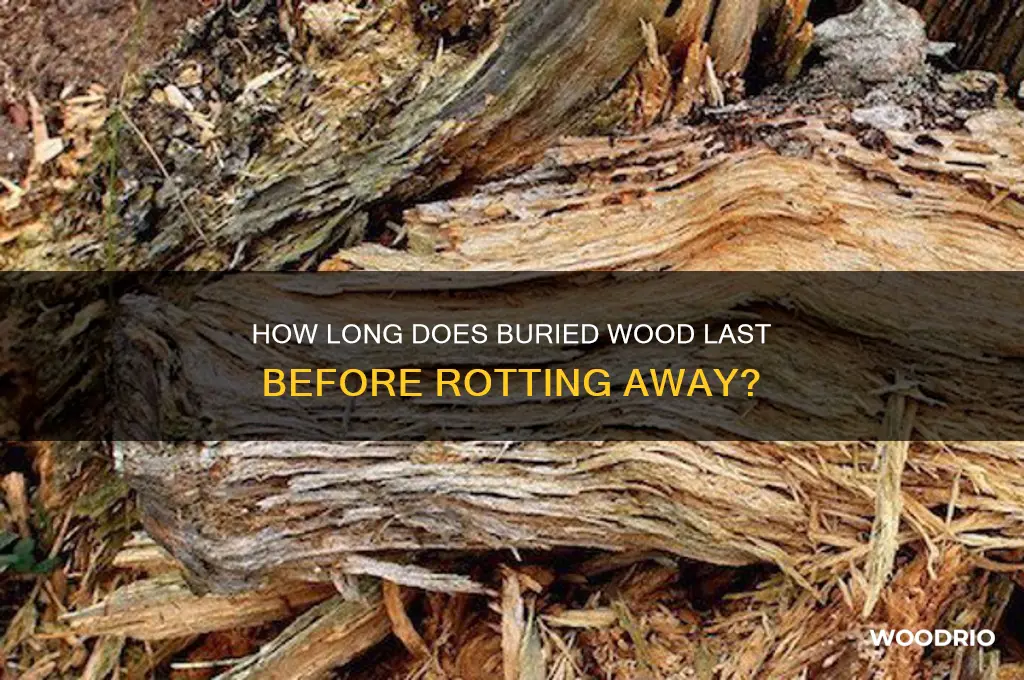

The longevity of buried wood before it rots depends on several factors, including the type of wood, environmental conditions, and the presence of microorganisms. Hardwoods like oak or teak generally last longer due to their natural resistance to decay, while softer woods like pine decompose more quickly. Burial in dry, well-drained soil with low oxygen levels can slow rotting, as anaerobic conditions hinder microbial activity. Conversely, moist, oxygen-rich environments accelerate decay by fostering fungi and bacteria growth. Additionally, treated or preserved wood can significantly extend its lifespan, often lasting decades or even centuries underground. Understanding these variables helps predict how long buried wood will endure before succumbing to rot.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Type of Wood | Hardwoods (e.g., oak, teak) last longer than softwoods (e.g., pine). |

| Moisture Content | High moisture accelerates decay; dry conditions slow it down. |

| Oxygen Availability | Anaerobic conditions (lack of oxygen) slow decay. |

| Soil Type | Acidic soils promote decay; alkaline soils inhibit it. |

| Temperature | Warmer temperatures speed up decay; colder temperatures slow it. |

| Microbial Activity | Presence of fungi and bacteria accelerates decomposition. |

| Burial Depth | Deeper burial reduces oxygen and slows decay. |

| Wood Treatment | Treated wood (e.g., pressure-treated) lasts significantly longer. |

| Estimated Lifespan (Untreated) | 5–10 years in wet, oxygen-rich soil; up to 50+ years in dry, anaerobic conditions. |

| Estimated Lifespan (Treated) | 40+ years, depending on treatment type and conditions. |

Explore related products

$14.99

$21.04

What You'll Learn

Climate impact on wood decay

Wood buried in oxygen-depleted environments, like deep soil or waterlogged areas, can persist for centuries—even millennia—due to slowed microbial activity. However, climate plays a decisive role in accelerating or decelerating this decay process. Temperature, humidity, and precipitation patterns directly influence the metabolic rates of fungi and bacteria responsible for wood degradation. For instance, in tropical regions with high temperatures and consistent moisture, wood buried just 12 inches underground can decompose within 5–10 years. Conversely, in arid climates like deserts, buried wood may remain intact for over 50 years due to low microbial activity.

Consider the practical implications for construction or archaeological preservation. In temperate zones with moderate rainfall, burying wood at depths greater than 24 inches can extend its lifespan to 20–30 years, as cooler temperatures and reduced oxygen slow decay. However, in flood-prone areas with fluctuating water tables, wood decay accelerates dramatically. To mitigate this, treat wood with borate or copper-based preservatives before burial, which can double its lifespan even in humid climates.

A comparative analysis reveals that wood decay in cold climates, such as boreal forests, occurs at a glacial pace. Temperatures below 50°F (10°C) significantly hinder microbial growth, allowing buried wood to endure for over 100 years. Yet, permafrost regions present a paradox: while frozen soil preserves wood, thawing due to climate change exposes it to rapid decay. For example, ancient wooden artifacts in Siberia, once protected by permafrost, are now deteriorating within years of exposure to warmer temperatures.

To maximize wood longevity in any climate, follow these steps: first, choose rot-resistant species like cedar or redwood. Second, bury wood in well-drained soil to minimize moisture retention. Third, apply a breathable, water-repellent sealant to reduce fungal penetration. In humid climates, elevate buried wood slightly using gravel layers to improve aeration. Finally, monitor buried wood annually for signs of decay, especially in regions with erratic weather patterns.

The takeaway is clear: climate is not just a backdrop but an active participant in wood decay. By understanding its mechanisms, you can strategically manipulate burial conditions to preserve wood for decades—or even centuries. Whether for landscaping, archaeology, or construction, tailoring your approach to local climate ensures buried wood endures as long as possible.

Understanding Standard Wood Lengths: A Comprehensive Guide to Lumber Sizes

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Soil type and moisture levels

Wood buried in soil faces a complex interplay of factors that determine its longevity, and soil type and moisture levels are among the most critical. Clay-rich soils, for instance, retain water longer due to their dense structure, creating a consistently damp environment that accelerates rot. In contrast, sandy soils drain quickly, reducing moisture contact with the wood and potentially extending its lifespan. Loamy soils, a balanced mix of sand, silt, and clay, offer moderate drainage and moisture retention, providing a middle ground for wood preservation. Understanding these soil characteristics allows for informed decisions when burying wood, whether for construction, landscaping, or other purposes.

Moisture levels in the soil act as a catalyst for decay, as they create the ideal conditions for fungi and bacteria to thrive. Wood buried in waterlogged soil can rot within 5 to 10 years, whereas in well-drained soil, it may persist for 20 years or more. To mitigate this, consider elevating the wood slightly above the surrounding soil or incorporating gravel layers to improve drainage. For projects requiring long-term durability, such as fence posts or foundation supports, treat the wood with preservatives like creosote or copper azole before burial. These treatments form a barrier against moisture and pests, significantly slowing the rotting process.

A comparative analysis reveals that soil pH also plays a subtle role in wood decay. Acidic soils (pH below 6) tend to accelerate rot by fostering the growth of decay-causing microorganisms, while alkaline soils (pH above 7) can inhibit their activity. Testing the soil pH and amending it with lime or sulfur, if necessary, can create a less hospitable environment for wood-destroying organisms. Additionally, burying wood in raised beds or mounds can reduce its exposure to standing water, particularly in regions with high rainfall or poor natural drainage.

For practical application, monitor soil moisture levels regularly, especially after heavy rains or in low-lying areas. Installing drainage systems, such as French drains or perforated pipes, can redirect excess water away from buried wood. In agricultural settings, rotating crops or planting moisture-absorbing species nearby can help manage soil wetness. When burying wood in humid climates, pair it with breathable barriers like geotextile fabric to minimize direct soil contact while allowing air circulation. By tailoring these strategies to specific soil types and moisture conditions, you can maximize the lifespan of buried wood and reduce the need for frequent replacements.

Wood vs. Plastic Toilet Seats: Which Material Offers Greater Durability?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Wood species resistance to rot

The lifespan of buried wood varies dramatically based on species, with some lasting decades while others disintegrate within years. This disparity hinges on natural resistance to decay, a trait influenced by chemical compounds like tannins, oils, and resins that deter fungi and insects. For instance, black locust and cedar can endure over 25 years in soil due to their high tannin content, whereas pine, lacking these protective chemicals, often rots within 5–10 years. Understanding these differences is crucial for projects like fencing, landscaping, or foundation supports, where longevity directly impacts durability and maintenance costs.

Selecting the right wood species for burial requires balancing cost, availability, and resistance. Tropical hardwoods like teak and ipe offer exceptional durability, often lasting 40+ years, but their high price and environmental concerns make them impractical for many applications. Alternatively, domestically sourced options like redwood and cypress provide moderate resistance at a lower cost, typically enduring 15–20 years. For budget-conscious projects, pressure-treated pine, infused with preservatives, can rival the lifespan of naturally resistant woods, though its chemicals may leach into soil over time.

Environmental factors also play a pivotal role in how wood species resist rot. Moisture levels, soil pH, and temperature fluctuations accelerate decay even in naturally durable woods. For example, cedar performs well in dry, well-drained soils but deteriorates faster in waterlogged conditions. To maximize longevity, pair species with their ideal environment: use black locust for wet areas, redwood for moderate moisture, and treated pine for high-humidity zones. Additionally, elevating wood slightly above ground or using gravel beds can reduce direct soil contact, further preserving its integrity.

For those seeking eco-friendly alternatives, consider modifying wood through thermal treatment or acetylation. These processes enhance resistance without chemicals, extending lifespan to 20–30 years. Thermally modified ash or acetylated pine, for instance, mimic the durability of tropical hardwoods while maintaining sustainability. However, these treatments increase costs by 20–50%, making them suitable primarily for high-value projects. Pairing such modified woods with proper installation techniques, like sealing ends and avoiding direct soil contact, ensures optimal performance even in challenging conditions.

Finally, while species resistance is key, maintenance and design choices amplify wood’s buried lifespan. Applying borate or copper naphthenate preservatives can add 5–10 years to moderately resistant woods like hemlock or fir. Regular inspections for cracks or insect damage, coupled with prompt repairs, further extend usability. For critical structures, combine resistant species with non-wood components, such as concrete footings or metal brackets, to distribute stress and minimize decay. By integrating species selection with proactive care, buried wood can serve reliably for decades, even in demanding environments.

Faux Wood vs. Real Wood Blinds: Which Lasts Longer?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$9.99

Presence of insects and fungi

In the subterranean realm where wood meets soil, insects and fungi emerge as the primary architects of decay. These organisms thrive in the damp, dark conditions that buried wood provides, accelerating the rotting process through their relentless activity. Termites, for instance, are voracious consumers of cellulose, the primary component of wood. A single termite colony can compromise the structural integrity of buried wood within months, especially in warm, humid climates where their populations flourish. Similarly, fungi like white rot and brown rot species secrete enzymes that break down lignin and cellulose, turning solid timber into crumbly debris. Understanding their role is crucial for anyone seeking to predict or mitigate wood decay.

To combat the onslaught of insects, preventive measures are key. Treating wood with borate-based preservatives before burial can deter termites and other wood-boring pests. These chemicals penetrate the wood fibers, creating a toxic barrier that insects avoid. For existing infestations, bait stations containing slow-acting insecticides can be strategically placed to eliminate colonies without harming the surrounding ecosystem. However, timing is critical; once insects establish a foothold, their damage can be irreversible. Regular inspections of buried wood structures, such as fence posts or foundations, can catch early signs of infestation, allowing for prompt intervention.

Fungi, on the other hand, require a different approach. Moisture control is paramount, as fungi need water to grow and reproduce. Ensuring proper drainage around buried wood and using water-repellent treatments can significantly reduce fungal activity. In cases where fungi have already taken hold, antifungal agents like copper naphthenate can be applied to halt their spread. Interestingly, some fungi are more destructive than others; brown rot fungi, for example, degrade cellulose faster than white rot fungi, which target lignin. Identifying the specific fungal species at play can guide more targeted treatment strategies.

Comparing the impact of insects and fungi reveals a symbiotic relationship in wood decay. Insects often create entry points for fungal spores by tunneling through the wood, while fungi weaken the wood structure, making it easier for insects to penetrate. This interplay underscores the importance of addressing both threats simultaneously. For instance, combining insecticidal treatments with moisture barriers can create a dual defense system that prolongs the lifespan of buried wood. In regions with high insect and fungal activity, such as tropical or temperate rainforests, these measures are not optional but essential.

Practically speaking, the presence of insects and fungi means that buried wood rarely lasts more than 5–10 years without intervention. However, with proper treatment and maintenance, this timeline can be extended significantly. For example, pressure-treated wood, infused with preservatives to repel both insects and fungi, can endure for 20–40 years underground. For those seeking eco-friendly alternatives, natural repellents like neem oil or essential oils derived from cloves and thyme can offer moderate protection. Ultimately, the battle against wood decay is won through vigilance, proactive treatment, and an understanding of the adversaries at play.

Wood Pellets Lifespan: How Long Do They Last and Stay Effective?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Depth and oxygen availability underground

Buried wood's longevity hinges on the oxygen levels at its burial depth, a factor often overlooked in discussions of decay. Below ground, oxygen availability decreases with depth due to soil compaction and the presence of water, which fills pore spaces and limits air infiltration. In the upper soil layers, where oxygen is more abundant, aerobic microorganisms thrive, accelerating wood decomposition. However, as depth increases, anaerobic conditions dominate, slowing decay but allowing different organisms, like fungi, to take over. This shift in microbial activity means that wood buried deeper than 12 to 18 inches may persist longer, though the exact duration depends on soil type, moisture, and temperature.

To maximize wood preservation, consider burying it below the oxygen-rich topsoil layer, typically the first 6 to 12 inches. At this depth, the transition to anaerobic conditions begins, significantly reducing aerobic microbial activity. For practical applications, such as preserving wooden posts or artifacts, burying them at least 18 inches deep can extend their lifespan by decades. However, this method is not foolproof; waterlogged conditions at deeper levels can still foster anaerobic decay, albeit at a slower pace. Monitoring soil moisture and ensuring proper drainage can further mitigate risks.

A comparative analysis reveals that shallow burials (less than 6 inches) expose wood to rapid decay due to high oxygen levels and increased microbial activity. In contrast, burials deeper than 24 inches may encounter water tables in some regions, creating anaerobic but waterlogged conditions that promote slow but steady decay. The sweet spot for preservation lies between 18 and 24 inches, where oxygen is minimal, and waterlogging is less likely. This depth range strikes a balance, slowing decay without introducing excessive moisture.

For those seeking to preserve wood long-term, combining depth with other methods, such as treating wood with preservatives or using naturally rot-resistant species, can yield the best results. For instance, applying a borate solution before burial can inhibit fungal growth, even in deeper, anaerobic environments. Additionally, choosing hardwoods like cedar or oak, which have natural resins that deter decay, can enhance durability. By understanding the interplay between depth and oxygen availability, one can strategically bury wood to significantly extend its lifespan, whether for functional or historical preservation purposes.

Mastering Wood Glue Clamping: Optimal Time for Strong, Durable Joints

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The time it takes for buried wood to rot completely depends on factors like soil moisture, temperature, and wood type. In moist, warm conditions, wood can decay in 5–10 years, while in dry or cold soil, it may last 50+ years or longer.

Burying wood in soil can speed up rotting if the soil is moist and contains fungi and bacteria, which break down the wood. However, in dry or anaerobic (oxygen-depleted) soil, the rotting process slows down significantly.

Treated wood is more resistant to rot but not immune. While it can last 20–40 years when buried, eventual decay is still possible, especially if the treatment chemicals leach out or the wood is exposed to highly corrosive soil conditions.

![FORTRESS 360° Cricket Sight Screen [Test & T20 Grade]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/61e7Vnjm93L._AC_UL320_.jpg)