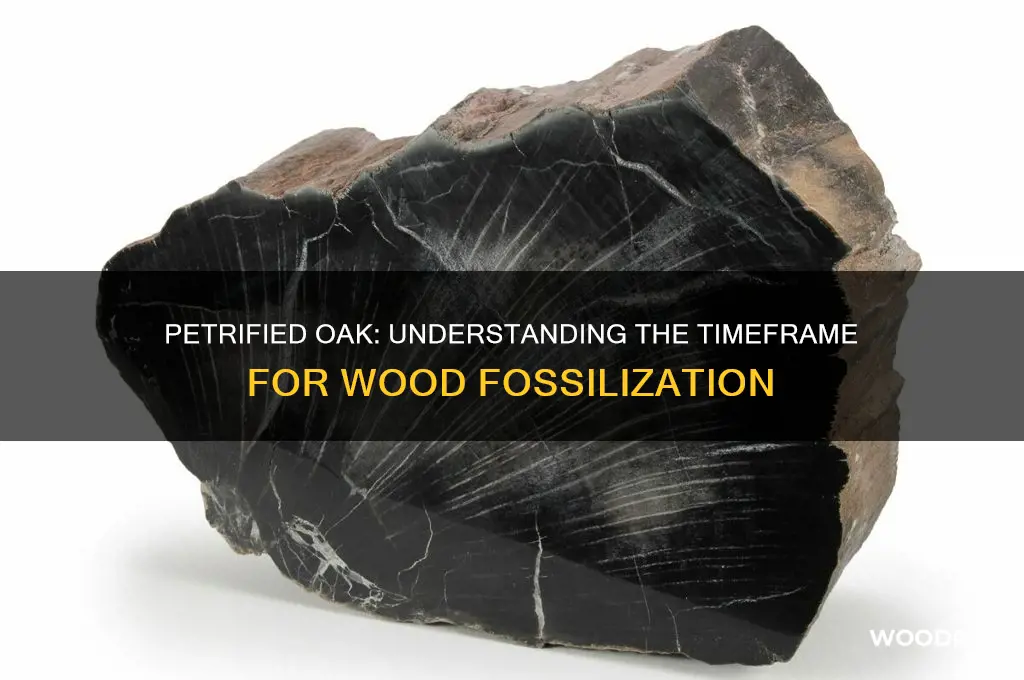

Petrification of oak wood is a fascinating geological process that transforms organic material into stone over an incredibly long period. This process, known as permineralization, occurs when minerals gradually replace the organic matter in the wood, preserving its cellular structure while turning it into a rock-like substance. For oak wood to petrify, it typically requires specific conditions, such as burial in sediment rich in minerals like silica, a lack of oxygen to prevent decay, and a stable environment over millions of years. While the exact duration varies depending on these factors, petrification of oak wood generally takes at least several million years, making it a testament to the slow and relentless forces of nature.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Time for Oak Wood to Petrify | Typically takes millions of years under ideal conditions. |

| Process | Requires burial in sediment, mineral-rich water, and absence of oxygen. |

| Mineral Replacement | Silica (quartz) is the most common mineral replacing wood cells. |

| Preservation Factors | Depends on pH levels, temperature, and pressure of the environment. |

| Fossilization vs. Petrification | Petrification is a subset of fossilization, specifically involving mineral replacement. |

| Examples | Famous examples include Petrified Forest National Park in Arizona, USA. |

| Softwood vs. Hardwood | Oak (hardwood) petrifies more slowly than softwoods due to denser cell structure. |

| Human-Accelerated Petrification | Can be simulated in labs over decades using silica-rich solutions, but not true petrification. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Factors Affecting Petrification: Climate, soil type, moisture, and mineral content influence oak wood petrification rates

- Initial Decay Process: Fungi, bacteria, and insects break down wood before mineralization begins

- Mineralization Timeline: Silica or calcite infiltration can take centuries to fully petrify oak wood

- Environmental Conditions: Buried wood in anaerobic, mineral-rich environments petrifies faster than exposed wood

- Historical Examples: Fossilized oak wood found in sedimentary layers dates back millions of years

Factors Affecting Petrification: Climate, soil type, moisture, and mineral content influence oak wood petrification rates

Petrification of oak wood is a geological process that transforms organic material into stone, but the timeline varies dramatically based on environmental conditions. Climate plays a pivotal role: in arid regions, where temperatures fluctuate widely, the process can take millions of years due to slow mineral infiltration. Conversely, in humid, tropical climates, the presence of abundant water accelerates mineral transport, potentially reducing petrification time to a few hundred thousand years. For instance, oak wood buried in the volcanic ash of Yellowstone might petrify faster than that submerged in the peat bogs of Ireland, where anaerobic conditions slow decay but delay mineralization.

Soil type acts as a silent architect of petrification, dictating the availability of minerals and the rate of water flow. Sandy soils, with their large particles, allow rapid water movement but offer limited mineral contact, prolonging the process. Clay-rich soils, however, retain moisture and minerals, creating an ideal environment for silica or calcite to permeate the wood’s cellular structure. A practical tip for enthusiasts: burying oak wood in clay-heavy soil near a mineral-rich water source, like a limestone spring, can simulate optimal petrification conditions, though results still require centuries.

Moisture is a double-edged sword in petrification. While it facilitates mineral transport, excessive water can lead to rot or erosion before minerals can preserve the wood. The ideal scenario is a consistent, moderate moisture level, such as that found in groundwater-saturated sediments. For experimental purposes, submerging oak wood in a solution of silica-rich water (10–20 ppm silica concentration) and maintaining a pH of 7–8 can mimic natural conditions, though this method still requires decades to show significant mineralization.

Mineral content is the final piece of the puzzle, determining both the speed and quality of petrification. Silica, found in volcanic ash or sandstone, is the most common mineral involved, but calcite from limestone or iron from ore deposits can also contribute. The presence of trace elements like manganese or copper can alter the wood’s color, creating the vibrant hues seen in petrified forests. To enhance mineralization, bury oak wood in soil amended with crushed quartz or limestone, ensuring direct contact with the minerals. However, avoid areas high in sulfur or organic acids, as these can degrade the wood before petrification occurs.

Understanding these factors allows for both appreciation of natural petrified wood and informed experimentation. While controlling all variables is impossible in nature, manipulating them in a controlled setting can yield fascinating results—though patience remains the most critical ingredient. Whether studying ancient specimens or creating new ones, the interplay of climate, soil, moisture, and minerals reveals the delicate balance required for oak wood to transform from tree to treasure.

Petrifying Wood: Understanding the Timeframe for Fossilization Process

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$29.99

Initial Decay Process: Fungi, bacteria, and insects break down wood before mineralization begins

The initial decay of oak wood is a complex, multifaceted process driven by fungi, bacteria, and insects working in tandem to break down its cellular structure. Fungi, particularly white rot and brown rot species, secrete enzymes that degrade lignin and cellulose, the primary components of wood. White rot fungi, such as *Trametes versicolor*, completely decompose both lignin and cellulose, leaving behind a bleached, stringy residue. Brown rot fungi, like *Postia placenta*, target cellulose, causing the wood to shrink, crack, and become brown and cuboidal in appearance. This fungal activity creates entry points for bacteria, which further decompose simpler organic compounds released by the fungi.

Insects, notably termites and wood-boring beetles, accelerate decay by fragmenting the wood into smaller pieces, increasing surface area for microbial colonization. Termites, for instance, ingest wood and break it down in their guts with the help of symbiotic protozoa, while beetles like the powderpost beetle (*Lyctus spp.*) create tunnels that expose fresh wood to fungal spores and moisture. This synergistic relationship between fungi, bacteria, and insects ensures that oak wood is efficiently reduced to a state where mineralization can begin. Without this initial decay, the wood’s dense structure would resist the infiltration of minerals necessary for petrification.

To observe this process in action, consider a fallen oak log in a humid forest environment. Within months, fungal hyphae penetrate the wood, visible as greenish or blackish stains on the surface. By the first year, insect activity becomes evident through boreholes and frass (wood dust). Over 2–5 years, the log softens, cracks, and loses structural integrity as cellulose and lignin are broken down. Practical tip: To slow decay in outdoor oak structures, apply borate-based wood preservatives, which inhibit fungal and insect activity by disrupting their metabolic processes.

Comparatively, oak wood in arid environments decays at a slower pace due to reduced fungal and bacterial activity, but insects like termites can still cause significant damage if present. In contrast, submerged oak, such as in wetlands or rivers, decays rapidly due to constant moisture and anaerobic bacteria, which produce acids that dissolve wood fibers. This highlights the importance of environmental conditions in dictating the speed and nature of initial decay.

The takeaway is that the initial decay process is not merely destruction but a necessary prelude to petrification. By breaking down complex organic matter into simpler compounds, fungi, bacteria, and insects prepare the wood for mineral infiltration. This stage typically lasts 5–50 years, depending on environmental factors, after which mineralization can proceed over centuries. Understanding and manipulating these decay agents—whether to preserve oak structures or study petrification—requires a nuanced approach that respects their ecological roles.

Durability of Wood Retaining Walls: Lifespan and Maintenance Tips

You may want to see also

Mineralization Timeline: Silica or calcite infiltration can take centuries to fully petrify oak wood

Petrification of oak wood is a geological process that hinges on the slow infiltration of minerals like silica or calcite into its cellular structure. Unlike rapid fossilization methods, this transformation requires a patient timeline, often spanning centuries. The process begins when oak wood is buried in sediment-rich environments, such as riverbeds or volcanic ash layers, where groundwater saturated with dissolved minerals can permeate the wood’s pores. Over time, these minerals precipitate out, replacing organic matter cell by cell with crystalline structures, preserving the wood’s original texture and shape.

Silica, derived from quartz-rich sediments, is the most common mineral involved in oak wood petrification. Groundwater percolating through silica-rich rocks dissolves the mineral, transporting it into the buried wood. As the water evaporates or conditions change, silica precipitates as opal or chalcedony, gradually hardening the wood. This phase alone can take 100 to 200 years, depending on factors like temperature, pH, and mineral concentration. Calcite petrification, though less common, follows a similar process but involves calcium carbonate from limestone or marine environments, often resulting in a whiter, more brittle fossilized wood.

The timeline for complete petrification is influenced by environmental conditions. Ideal settings include arid climates with stable groundwater flow, where minerals can accumulate steadily without being washed away. For instance, the petrified forests of Arizona showcase oak and other woods fully mineralized over millions of years due to consistent silica infiltration from volcanic ash. In contrast, oak wood buried in fluctuating water tables or acidic soils may degrade before significant mineralization occurs, underscoring the need for specific conditions to prolong the process.

Practical observation of petrification in progress is rare, as it occurs beneath the Earth’s surface. However, partially petrified oak wood can sometimes be found in riverbanks or construction sites, where cross-sections reveal a gradient from mineralized exterior to organic core. Collectors and researchers can identify early stages by testing hardness—partially petrified wood will scratch glass due to silica content, while fully petrified specimens are nearly as hard as quartz. Accelerating this process artificially is nearly impossible, as it relies on natural geological conditions that cannot be replicated on human timescales.

Understanding the mineralization timeline of oak wood petrification offers insights into Earth’s geological patience. While centuries may pass before a piece of oak is fully transformed, each stage of infiltration and crystallization tells a story of environmental interaction and preservation. For enthusiasts or researchers, recognizing the early signs of petrification—such as weight increase or surface sheen—can guide the identification of specimens in transitional phases. Ultimately, this process reminds us that nature’s artistry unfolds not in moments, but in epochs.

Wood Respawn in The Long Dark: Survival Tips and Strategies

You may want to see also

Environmental Conditions: Buried wood in anaerobic, mineral-rich environments petrifies faster than exposed wood

The rate at which oak wood petrifies is not solely determined by time but significantly influenced by its environment. Buried wood, particularly in anaerobic, mineral-rich conditions, undergoes petrification at an accelerated pace compared to exposed wood. This process, known as permineralization, occurs when minerals dissolved in groundwater seep into the wood’s cellular structure, gradually replacing organic material with silica, calcite, or pyrite. The absence of oxygen in anaerobic environments prevents decay-causing microorganisms from thriving, preserving the wood’s structure long enough for mineralization to take place.

To understand why buried wood petrifies faster, consider the role of groundwater. In mineral-rich environments, such as riverbeds or volcanic ash deposits, groundwater acts as a mineral delivery system. For instance, silica-rich water can infiltrate oak wood, depositing quartz crystals in the cell walls over centuries. This process is far more efficient when the wood is shielded from air and sunlight, which would otherwise accelerate decomposition. Practical examples include petrified forests found in sedimentary basins, where layers of mud and silt buried wood rapidly, creating ideal conditions for preservation.

While the exact timeline for petrification varies, buried oak wood in optimal conditions can begin to petrify within 1,000 to 10,000 years, compared to exposed wood, which may take significantly longer or not petrify at all. For those interested in replicating this process, burying oak wood in a clay-rich soil or submerged in a mineral-rich body of water can expedite petrification. However, caution is advised: ensure the wood is fully covered to maintain anaerobic conditions, and avoid areas prone to erosion or disturbance.

A comparative analysis highlights the stark difference between environments. Exposed oak wood, subject to weathering and biological activity, often degrades completely within 50 to 100 years. In contrast, wood buried in anaerobic, mineral-rich environments retains its structure, slowly transforming into stone. This disparity underscores the critical role of environmental conditions in the petrification process, making burial a key factor for preservation and mineralization.

In conclusion, the petrification of oak wood is a testament to the interplay between time and environment. By burying wood in anaerobic, mineral-rich settings, one can significantly shorten the timeline for petrification, turning organic matter into a lasting geological artifact. This knowledge not only enriches our understanding of natural processes but also offers practical insights for those seeking to preserve or replicate this ancient transformation.

Faux Wood vs. Real Wood Blinds: Which Lasts Longer?

You may want to see also

Historical Examples: Fossilized oak wood found in sedimentary layers dates back millions of years

Fossilized oak wood, entombed within sedimentary layers, offers a tangible link to Earth’s ancient past. These specimens, often unearthed in coal swamps or riverbeds, date back millions of years, with some examples tracing to the Paleocene or Eocene epochs. The process of petrification, where organic material transforms into stone, requires specific conditions: rapid burial, mineral-rich water, and immense pressure over vast timescales. Such fossils are not merely curiosities; they provide critical insights into prehistoric climates, ecosystems, and the evolution of plant life.

Analyzing these fossils reveals a meticulous natural process. Groundwater saturated with silica or calcite seeps into the buried wood, replacing cellulose and lignin with minerals cell by cell. This preservation is so precise that original growth rings and even cellular structures can remain visible under a microscope. For instance, fossilized oak from the Baltic region, dating to 40–50 million years ago, showcases this level of detail, allowing paleobotanists to study ancient tree physiology and growth patterns. Such findings underscore the importance of sedimentary environments in capturing and preserving biological history.

Practical examination of these fossils often begins with field identification. Look for telltale signs of petrification: weight (heavier than normal wood due to mineralization), hardness (resistant to scratching), and cross-sectional patterns. Collectors and researchers should handle specimens with care, avoiding exposure to moisture or temperature extremes, which can cause cracking. For educational purposes, thin sections of fossilized oak can be prepared for microscopic study, offering students a direct view of the petrification process.

Comparatively, fossilized oak stands apart from other petrified woods, such as those from conifers or ferns, due to its distinct cellular structure and growth patterns. Oak’s dense, ring-porous wood often retains more detail during fossilization, making it a prized subject for study. In contrast, softer woods may degrade more rapidly, leaving less-defined fossils. This durability highlights oak’s unique role in the fossil record, serving as a robust marker of ancient forests and the environments they inhabited.

Persuasively, the study of fossilized oak wood is not just an academic exercise but a call to action. These fossils remind us of Earth’s dynamic history and the fragility of ecosystems. As climate change accelerates, understanding past environmental shifts—documented in these ancient specimens—can inform conservation strategies. By preserving and studying fossilized oak, we honor the planet’s history and equip ourselves to protect its future. Each piece of petrified wood is a silent witness to millions of years of change, urging us to learn from the past.

How Long Will a 40lb Bag of Wood Pellets Last?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Petrification of oak wood typically takes thousands to millions of years, depending on environmental conditions such as mineral-rich water, consistent burial, and lack of oxygen.

Key factors include the presence of silica or calcite in groundwater, a stable, sediment-rich environment, and protection from decay, such as being buried under layers of sediment or volcanic ash.

While natural petrification is extremely slow, laboratory-controlled conditions using high-pressure mineral solutions can accelerate the process, but it still takes years to decades to achieve significant petrification.