Petrifying wood, a process also known as fossilization or silicification, is a fascinating natural phenomenon that transforms organic material into stone over an incredibly long period. This process occurs when wood is buried under sediment and groundwater rich in minerals, typically silica, gradually infiltrates the cellular structure of the wood, replacing the organic matter with mineral deposits. The duration required for wood to petrify can vary significantly, ranging from thousands to millions of years, depending on factors such as the mineral content of the surrounding environment, temperature, and pressure. While the exact timeline is difficult to pinpoint, it is generally understood that petrification is a slow and meticulous process, resulting in stunningly preserved fossils that offer valuable insights into Earth’s geological and biological history.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Process Duration | Typically takes millions of years (natural process) |

| Accelerated Process | Laboratory conditions can reduce time to several months to a few years |

| Key Factors | Presence of silica-rich water, lack of oxygen, and consistent pressure |

| Mineral Composition | Primarily replaced by silica (quartz) |

| Preservation Quality | Depends on mineral infiltration rate and environmental stability |

| Common Locations | Found in sedimentary rock formations with volcanic ash or sand |

| Temperature Requirement | Optimal conditions range from 50°F to 150°F (10°C to 65°C) |

| pH Level | Neutral to slightly alkaline water (pH 7-8) is ideal |

| Wood Type | Hardwoods like oak or pine are more commonly petrified |

| Fossilization Stage | Petrification is the final stage of fossilization, replacing organic matter with minerals |

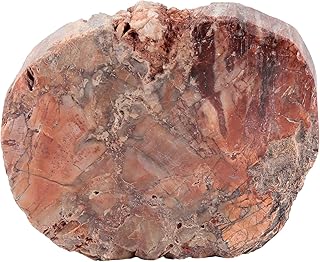

Explore related products

$39.5

What You'll Learn

- Factors Affecting Petrification Speed: Climate, mineral availability, and wood type influence the petrification process duration

- Initial Decay Stage: Wood must lose organic matter, which can take decades to centuries

- Mineral Infiltration Phase: Silica-rich water permeates wood cells, replacing organic material with minerals

- Complete Petrification Timeline: Full petrification typically spans thousands to millions of years

- Accelerated Petrification Methods: Modern techniques can shorten the process to months or years

Factors Affecting Petrification Speed: Climate, mineral availability, and wood type influence the petrification process duration

Petrification, the process by which wood transforms into stone, is not a quick affair. It’s a geological ballet that unfolds over millennia, but the speed at which it occurs is far from uniform. Three key factors—climate, mineral availability, and wood type—play pivotal roles in determining how long this transformation takes. Understanding these variables can demystify why some petrified wood forms in a mere 5,000 years, while others require 20 million.

Climate acts as the conductor of the petrification orchestra. In arid environments, where water is scarce, the process slows to a glacial pace. Minerals struggle to dissolve and permeate the wood, often resulting in incomplete petrification. Conversely, tropical or temperate climates with consistent moisture accelerate the process. For instance, wood buried in a riverbed with a steady flow of mineral-rich water can petrify in as little as 10,000 years. Temperature also matters; warmer climates speed up chemical reactions, while colder regions retard them. A practical tip for enthusiasts: if you’re attempting artificial petrification, maintain a temperature of 120–150°F (49–65°C) to mimic optimal natural conditions.

Mineral availability is the lifeblood of petrification. Without silica, calcite, or pyrite, wood cannot transform into stone. Regions rich in volcanic ash or sedimentary rock provide an abundance of these minerals, drastically shortening the petrification timeline. For example, the Petrified Forest National Park in Arizona owes its existence to silica-laden groundwater that seeped through volcanic ash deposits. If you’re experimenting with petrification at home, use a solution of 1 part silica gel to 10 parts water, ensuring the wood is fully submerged for consistent mineral exposure.

Wood type is the unsung hero of this process. Dense hardwoods like oak or maple petrify more slowly than softer woods like pine or cedar. The cellular structure of the wood determines how easily minerals can infiltrate and replace organic material. Conifers, with their resinous sap, often preserve better but petrify more slowly due to their natural resistance to decay. A comparative analysis reveals that a pine log might take 50% longer to petrify than a similarly sized oak log under identical conditions. For those attempting petrification, start with softer woods like balsa or aspen to observe results within a few months, albeit on a miniature scale.

In conclusion, petrification speed is a delicate interplay of environmental and material factors. By manipulating climate, ensuring mineral availability, and selecting the right wood type, one can significantly influence the duration of this ancient process. Whether you’re a geologist, hobbyist, or simply curious, understanding these factors transforms petrification from a mystery into a science.

Durability of Pressure Treated Wood: Outdoor Lifespan Explained

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$6.99

Initial Decay Stage: Wood must lose organic matter, which can take decades to centuries

The initial decay stage of wood petrification is a slow, relentless process where organic matter is stripped away, leaving behind a skeletal structure primed for mineralization. This phase, often overlooked, is crucial because it determines the wood’s ability to fossilize. Without the removal of cellulose, lignin, and other organic compounds, minerals cannot infiltrate the cellular structure, halting petrification before it begins. Time is the primary factor here—decades to centuries are required for microorganisms, water, and oxygen to break down these complex molecules, depending on environmental conditions like temperature, moisture, and microbial activity.

Consider the environment in which wood is buried. In arid regions, decay slows to a crawl due to limited microbial activity, stretching this stage to centuries. Conversely, in warm, humid environments teeming with fungi and bacteria, decay accelerates, potentially reducing the timeline to mere decades. For example, wood submerged in anaerobic conditions (like deep sediment) may retain organic matter longer, as oxygen-dependent decay processes are hindered. Practical tip: To expedite this stage experimentally, bury wood in a mixture of soil and compost, which introduces decomposers and accelerates organic matter loss.

Comparatively, this stage mirrors the early phases of composting, where organic material is broken down into simpler forms. However, unlike composting, which aims for complete decomposition, petrification requires a delicate balance—enough decay to create voids for minerals, but not so much that the wood’s structure collapses. This is why controlled environments, such as those in laboratory settings, often use chemical treatments (e.g., weak acids) to simulate decay, reducing the timeline to months rather than centuries.

Persuasively, understanding this stage underscores the rarity of petrified wood. Not all buried wood survives this phase; most decomposes entirely, leaving no trace. Those that do persist enter a natural lottery, where mineral-rich water must be present at the right time to initiate fossilization. For enthusiasts or researchers, patience is non-negotiable. If attempting petrification artificially, monitor the wood’s density and color changes over time—a gradual shift from brown to gray indicates organic matter loss, signaling readiness for the next stage.

Descriptively, imagine a fallen tree in a riverbed, slowly sinking into sediment. Over decades, its bark softens, its interior hollows, and its weight decreases as organic compounds leach away. This transformation is invisible to the naked eye but foundational to its future as a fossil. The wood becomes a ghost of its former self, a latticework of cellulose fibers awaiting the slow infiltration of silica, calcite, or pyrite. This stage is not just decay—it’s a rebirth, a preparation for immortality in stone.

Brian's Survival: Time Spent in the Woods in 'Hatchet

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Mineral Infiltration Phase: Silica-rich water permeates wood cells, replacing organic material with minerals

The mineral infiltration phase is a pivotal stage in the petrification of wood, where silica-rich water acts as the primary agent of transformation. This process begins when wood is buried in sediment and exposed to groundwater saturated with dissolved minerals, particularly silica (SiO₂). As this water permeates the wood’s cellular structure, it initiates a slow but relentless replacement of organic material with mineral deposits. Over time, the wood’s original texture and structure are preserved, but its composition shifts from organic to inorganic, turning it into stone. This phase is not instantaneous; it requires specific conditions, such as a consistent supply of mineral-rich water and a stable environment, to proceed effectively.

To understand the mechanics of this phase, consider the role of silica in the petrification process. Silica, often derived from volcanic ash or surrounding sedimentary rocks, dissolves in groundwater and forms a gel-like substance when it encounters the wood. This gel gradually hardens, filling the wood’s cell walls and cavities. The key to successful mineral infiltration lies in the balance of silica concentration and pH levels in the water. Optimal conditions typically involve a silica concentration of 50–100 ppm and a slightly acidic to neutral pH (6.0–7.5). Deviations from these parameters can slow or halt the process, underscoring the precision required for petrification to occur.

Practical experiments in accelerating petrification often involve simulating these natural conditions in controlled environments. For instance, submerging wood in a solution of sodium silicate (water glass) at a concentration of 3–5% can mimic the silica-rich groundwater found in nature. The wood should be fully saturated, and the solution periodically replenished to maintain mineral levels. Temperature also plays a role; keeping the solution at 60–80°F (15–27°C) can expedite the process, though higher temperatures may risk damaging the wood’s structure. This method, while faster than natural petrification, still requires weeks to months to achieve noticeable mineralization.

Comparing natural and artificial petrification highlights the trade-offs between time and control. Natural petrification can take thousands to millions of years, depending on environmental factors, but it produces specimens of unparalleled detail and durability. Artificial methods, while significantly faster, often result in less uniform mineralization and may lack the intricate preservation seen in naturally petrified wood. For hobbyists or researchers, the choice between these approaches depends on the desired outcome: a quick, hands-on project or a long-term study of geological processes.

In conclusion, the mineral infiltration phase is a delicate interplay of chemistry, geology, and time. Whether occurring naturally over millennia or accelerated in a laboratory, the process hinges on the precise delivery of silica-rich water into wood cells. By understanding and manipulating these conditions, one can gain insights into both the science of petrification and the art of preserving organic material in stone. This phase is not just a step in petrification but a testament to nature’s ability to transform the ephemeral into the eternal.

How Long Does Wood Filler Take to Dry? A Quick Guide

You may want to see also

Explore related products

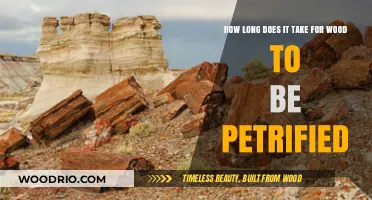

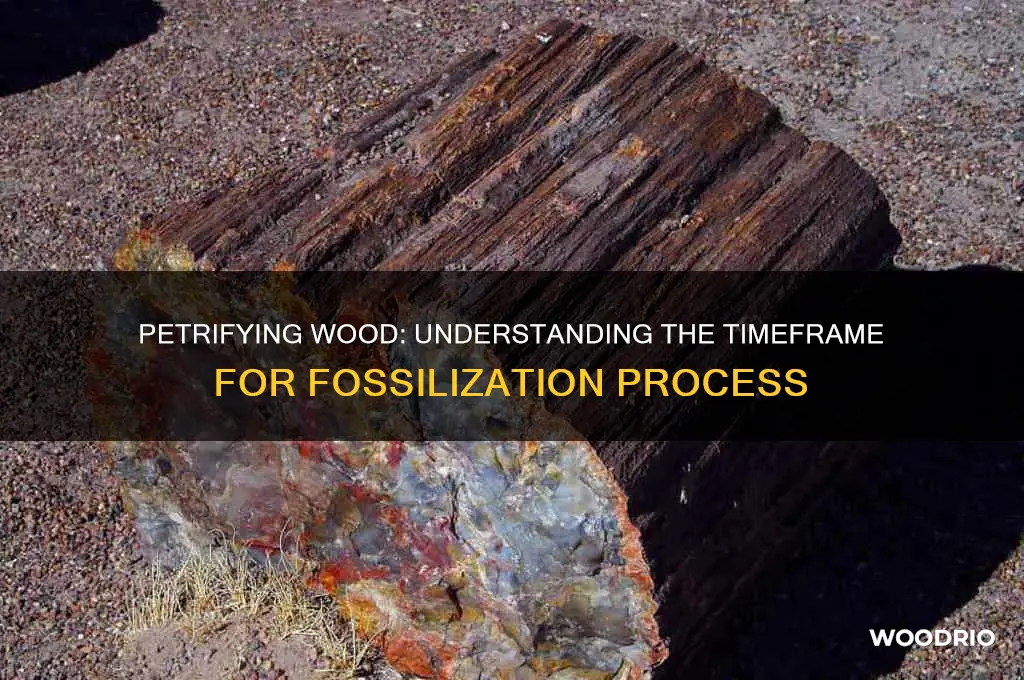

Complete Petrification Timeline: Full petrification typically spans thousands to millions of years

Petrification, the process by which organic materials like wood turn into stone, is a marvel of geological patience. Unlike quick transformations seen in nature, such as freezing or decay, petrification unfolds over vast timescales, often spanning thousands to millions of years. This duration is dictated by the intricate interplay of mineral-rich water, pressure, and the absence of oxygen, which together replace organic matter with minerals like silica, calcite, or pyrite. Understanding this timeline requires a deep dive into the stages of petrification, each of which contributes to the final fossilized masterpiece.

The first stage, permineralization, begins when wood is buried under sediment, shielding it from decay. Groundwater rich in dissolved minerals seeps into the wood’s cellular structure, gradually filling its pores. This process alone can take centuries to millennia, depending on the mineral concentration and the wood’s density. For instance, coniferous woods, with their resinous tissues, may petrify faster than deciduous woods due to their natural resistance to decay. However, even under ideal conditions, this stage is just the beginning of a long journey.

Next comes replacement, where the original organic material is slowly dissolved and replaced by minerals. This phase is the most time-consuming, often requiring hundreds of thousands to millions of years. The rate depends on factors like temperature, pH levels, and the type of minerals present. For example, silica, a common mineral in petrified wood, solidifies more slowly than calcite. During this stage, the wood’s cellular structure is meticulously replicated, preserving details like growth rings and even cellular patterns, a testament to the process’s precision.

Finally, lithification occurs, where the mineralized wood hardens into stone. This stage solidifies the transformation, turning the once-living tissue into a durable fossil. While this phase is relatively quicker than the previous ones, it still demands tens of thousands of years to complete. The result is a fossilized artifact that can withstand erosion and time, offering a window into ancient ecosystems.

Practical tips for observing petrification in action include visiting sites like the Petrified Forest National Park in Arizona, where 225-million-year-old logs showcase the process’s end result. For those interested in experimenting, burying wood in mineral-rich sediment and monitoring it over decades (or generations) can provide a glimpse into the early stages. However, replicating full petrification at home is impossible due to the timescale involved. Instead, appreciating the process through existing fossils highlights the Earth’s ability to transform life into enduring art.

In conclusion, petrification is a testament to nature’s patience, unfolding over epochs rather than eras. Each stage—permineralization, replacement, and lithification—contributes to a timeline that dwarfs human lifespans. By understanding this process, we gain not only scientific insight but also a deeper appreciation for the geological forces that shape our world.

Optimal Clamping Time for Wood Glue: A Comprehensive Guide

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Accelerated Petrification Methods: Modern techniques can shorten the process to months or years

Petrification, the process of transforming wood into stone, traditionally takes thousands of years under natural conditions. However, modern techniques have emerged that can accelerate this process to mere months or years, making it feasible for artists, scientists, and hobbyists alike. These methods leverage advancements in chemistry, pressure, and temperature control to replicate the mineralization process at an unprecedented pace. By understanding and applying these techniques, one can create petrified wood specimens with remarkable efficiency and precision.

One of the most effective accelerated petrification methods involves the use of silica-rich solutions and controlled environments. To begin, prepare a solution of sodium silicate (also known as water glass) diluted in water, typically at a concentration of 10–20%. Submerge the wood specimen in this solution, ensuring it is fully saturated. Over time, the silica will permeate the wood’s cellular structure. To expedite the process, apply heat—ideally maintaining the solution at 60–80°C (140–176°F) for several weeks. This heat accelerates the polymerization of silica within the wood, effectively turning it into a stone-like material. Caution: Always use protective gear and ensure proper ventilation when handling chemicals.

Another innovative approach combines pressure and mineral infiltration to achieve rapid petrification. This method involves placing the wood in a high-pressure chamber filled with a mineral-rich solution, such as calcium carbonate or silica gel. The pressure, typically around 1,000–2,000 psi, forces the minerals into the wood’s pores and cell walls. Over a period of 3–6 months, the wood undergoes a dramatic transformation, emerging as a hardened, stone-like object. This technique is particularly useful for larger specimens or those requiring a more uniform mineralization.

For those seeking a more accessible and cost-effective method, vacuum impregnation offers a viable alternative. Start by placing the wood in a vacuum chamber to remove air from its cells. Once the wood is fully degassed, introduce a silica or mineral solution into the chamber, allowing it to penetrate the wood under vacuum conditions. This process can be repeated multiple times to ensure thorough saturation. After impregnation, cure the specimen in a warm environment (around 50–60°C or 122–140°F) for 1–2 months. The result is a petrified wood piece that retains its original structure but with significantly enhanced durability.

While these accelerated methods offer remarkable speed and control, they require careful execution to avoid common pitfalls. Over-saturation or excessive heat can lead to cracking or uneven mineralization, so monitoring the process is crucial. Additionally, the choice of minerals and solutions can influence the final appearance and properties of the petrified wood. For instance, silica-based solutions yield a more translucent, glass-like finish, while calcium carbonate produces a matte, stone-like texture. Experimentation and attention to detail are key to mastering these techniques and achieving the desired outcome.

In conclusion, accelerated petrification methods have revolutionized the way we approach this ancient process, making it accessible and practical for modern applications. Whether for artistic endeavors, scientific research, or personal projects, these techniques offer a fascinating blend of chemistry, physics, and creativity. By following the outlined steps and exercising caution, anyone can transform ordinary wood into a lasting, stone-like masterpiece in a fraction of the time nature would require.

Polyurethane Drying Time: Factors Affecting Wood Finishing Process

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Natural petrification of wood can take millions of years, usually between 5 to 50 million years, depending on environmental conditions like mineral-rich water and consistent pressure.

Yes, wood can be petrified artificially through processes like silicification, which can take several months to a few years, depending on the method and materials used.

Key factors include the presence of mineral-rich water, temperature, pressure, the type of wood, and the availability of minerals like silica or calcite.

Yes, petrified wood is fully transformed into stone through mineral replacement. The time required depends on how thoroughly the organic material is replaced by minerals.

Yes, the process can be accelerated artificially by using high-pressure environments, concentrated mineral solutions, and controlled temperatures, reducing the time from millions of years to months or years.