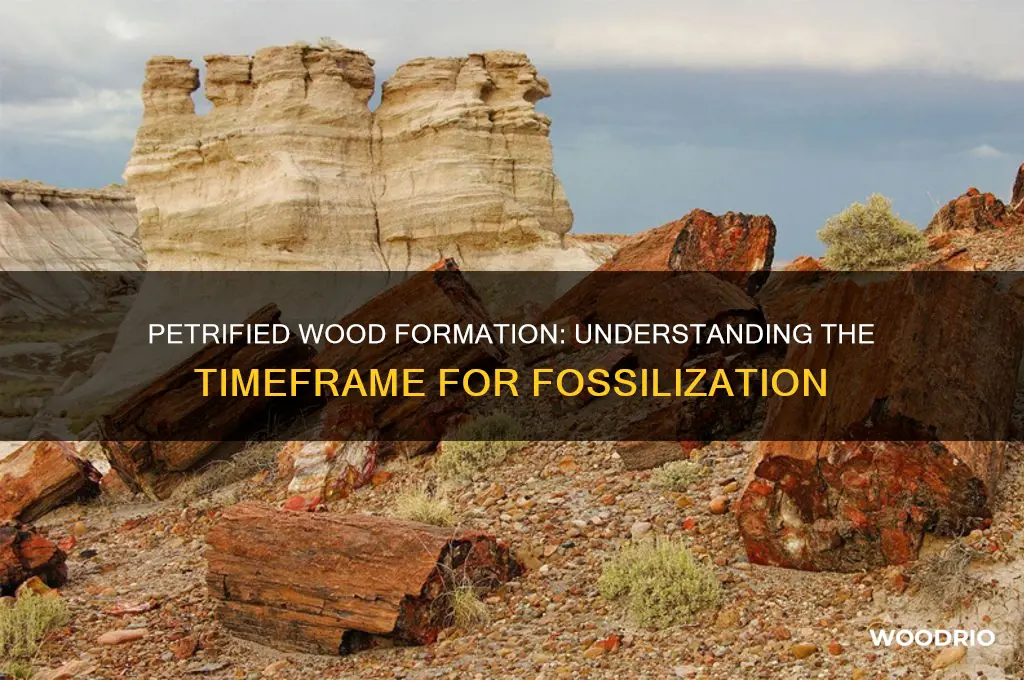

Petrification, the process by which wood transforms into stone, is a fascinating geological phenomenon that occurs over millions of years. It begins when a tree is buried under sediment, such as mud, volcanic ash, or sand, which shields it from oxygen and decay. Over time, groundwater rich in minerals like silica, calcite, and pyrite seeps into the wood, gradually replacing its organic cells with these minerals in a process called permineralization. This slow transformation preserves the wood’s original structure, including its rings and texture, while turning it into a durable, stone-like material. The entire process typically takes anywhere from 5 million to 20 million years, depending on factors like the mineral content of the surrounding environment, temperature, and pressure. As a result, petrified wood offers a unique glimpse into Earth’s ancient past, showcasing the intersection of biology and geology.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Timeframe for Petrification | Typically takes millions of years (e.g., 10 million years or more). |

| Key Factors Influencing Speed | - Mineral-rich water availability - Burial depth - Temperature and pressure conditions |

| Initial Stage (Permineralization) | Begins within hundreds to thousands of years after burial. |

| Complete Petrification | Requires millions of years for full mineral replacement. |

| Optimal Conditions | Anaerobic (oxygen-free) environments, such as deep sediment or volcanic ash. |

| Minerals Involved | Primarily silica (quartz), calcite, pyrite, or other minerals. |

| Preservation of Structure | Original wood cell structure is preserved due to slow mineral replacement. |

| Examples in Nature | Petrified forests (e.g., Petrified Forest National Park, Arizona) formed over 200+ million years. |

| Human-Accelerated Petrification | Experimental methods can reduce time to months to years, but not natural. |

Explore related products

$64.57 $77.99

What You'll Learn

Factors affecting petrification time

Petrification, the process by which wood transforms into stone, is not a swift event but a geological marathon. The timeline varies dramatically, influenced by a complex interplay of environmental and material factors. Understanding these factors is crucial for anyone curious about the ancient process or involved in paleontology, geology, or even landscaping with petrified wood.

Here’s a breakdown of the key elements that dictate how long it takes for wood to petrify:

Mineral Availability and Composition: The presence and type of minerals in the surrounding sediment are pivotal. Silica, often from volcanic ash or groundwater, is the most common mineral involved in petrification. Higher concentrations of silica accelerate the process, as it readily infiltrates the wood’s cellular structure. For instance, wood buried in silica-rich environments like ancient riverbeds or volcanic regions may petrify within 1,000 to 10,000 years. In contrast, wood in mineral-poor settings could take millions of years to fully transform. Calcium carbonate and iron oxides also contribute, but their slower precipitation rates extend the timeline.

Environmental Conditions: Temperature and pressure play significant roles. Warmer environments increase the rate of chemical reactions, speeding up mineralization. For example, wood buried in geothermal areas might petrify in as little as 100 years due to elevated temperatures. Conversely, colder climates slow the process, often requiring hundreds of thousands of years. Pressure, typically from overlying sediment, helps compact the wood and facilitates mineral infiltration. Deep burial, such as in sedimentary basins, provides the necessary pressure but also isolates the wood from oxygen, preventing decay and preserving it longer for petrification.

Wood Type and Preservation: Not all wood petrifies equally. Dense hardwoods like oak or teak, with their robust cellular structures, are more likely to withstand the early stages of decay and mineralization. Softwoods like pine, with looser cell walls, may disintegrate before significant petrification occurs. Additionally, the initial state of the wood matters—freshly fallen wood with intact lignin and cellulose will take longer to petrify than wood already partially decayed or carbonized. Pre-treatment, such as exposure to acidic water that removes organic material, can shorten the overall process.

Water Flow and pH Levels: Groundwater acts as the transport medium for minerals, so its flow rate and chemistry are critical. Fast-moving water in porous sediments delivers minerals more efficiently, reducing petrification time to thousands of years. Stagnant or slow-moving water prolongs the process, often requiring millions of years. pH levels also influence mineral solubility and reaction rates. Neutral to slightly acidic water (pH 6–7) is ideal for silica precipitation, while highly acidic or alkaline conditions can hinder mineralization.

Biological Activity: Microorganisms can either aid or impede petrification. Fungi and bacteria that decompose wood may initially break it down, but they also create pathways for mineral infiltration. In some cases, microbial activity can accelerate petrification by increasing the wood’s porosity. However, if decomposition outpaces mineralization, the wood may be lost entirely. Anaerobic environments, where oxygen is scarce, slow biological decay and favor preservation, allowing more time for minerals to replace organic material.

In summary, petrification time is a delicate balance of mineral availability, environmental conditions, wood characteristics, water dynamics, and biological factors. While some wood may petrify in centuries under optimal conditions, others require millennia. For enthusiasts or researchers, understanding these factors not only deepens appreciation for petrified wood but also aids in identifying prime locations for discovery or replication in controlled settings.

Efficient Kiln Drying: Optimal Time for Perfectly Seasoned Wood

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Role of mineral composition in petrification

Petrification, the process by which wood transforms into stone, is heavily influenced by the mineral composition of the surrounding environment. Silica, primarily from volcanic ash or groundwater rich in dissolved quartz, is the most common mineral involved. When silica-laden water permeates buried wood, it gradually replaces the organic material cell by cell, preserving intricate structures like growth rings and even cellular details. This process, known as permineralization, is not exclusive to silica; other minerals like calcite, pyrite, and opal can also contribute, though less frequently. The type of mineral present dictates the final appearance and durability of the petrified wood, with silica-rich specimens often exhibiting vibrant colors and exceptional hardness.

The speed of petrification is directly tied to the availability and concentration of these minerals. In environments with high silica content, such as ancient riverbeds or volcanic regions, petrification can occur within thousands to tens of thousands of years. For instance, the renowned petrified forests in Arizona formed over 225 million years, but the silica-rich conditions accelerated the process compared to less mineralized settings. Conversely, in areas with lower mineral concentrations, petrification may take millions of years, if it occurs at all. This variability underscores the critical role of mineral composition in determining both the timeline and outcome of petrification.

Practical considerations for those interested in petrification include understanding the local geology. For hobbyists attempting to replicate petrification artificially, a solution of silica gel or sodium silicate can be used to accelerate the process. However, achieving results comparable to natural petrification requires precise control over factors like temperature, pH, and mineral concentration. For example, maintaining a pH of 6–8 and a temperature of 25–30°C (77–86°F) optimizes silica precipitation. Caution must be exercised when handling chemicals, and protective gear, including gloves and goggles, is essential.

Comparatively, natural petrification offers a masterclass in patience and precision. While artificial methods can produce petrified wood in months to years, nature’s process is a testament to geological time. The mineral composition not only determines the pace but also the aesthetic and structural qualities of the final product. For instance, calcite-rich petrification often results in a more brittle material, while silica imparts a glass-like luster and resilience. This distinction highlights why silica remains the mineral of choice for both natural and artificial petrification.

In conclusion, the role of mineral composition in petrification is both foundational and transformative. It governs the speed, structure, and beauty of the process, turning organic matter into enduring stone. Whether in nature or the lab, understanding and manipulating mineral content is key to mastering petrification. For enthusiasts and scientists alike, this knowledge opens doors to appreciating—and even recreating—one of Earth’s most fascinating geological phenomena.

Durability of Wood: Factors Affecting Longevity and Preservation Techniques

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Impact of environmental conditions on process

The process of wood petrification, or permineralization, is a geological transformation that turns organic material into stone over time. Environmental conditions play a pivotal role in determining the duration and success of this process, which can range from thousands to millions of years. Factors such as mineral-rich water, temperature, pressure, and the presence of specific chemicals significantly influence how quickly wood transitions from organic matter to fossilized remains. Understanding these conditions not only sheds light on the timeline but also highlights the delicate interplay between nature and time.

Consider the role of water, a primary catalyst in petrification. Groundwater rich in minerals like silica, calcite, or pyrite seeps into the wood, filling its cellular structure. The rate of petrification accelerates in environments where this mineral-laden water is abundant and consistently flows through the wood. For instance, wood buried in volcanic ash or near hot springs, where mineral-rich water is prevalent, petrifies faster than wood in arid or stagnant conditions. Practical tip: If preserving wood for petrification, ensure it is buried in an area with consistent groundwater flow and high mineral content, such as near mineral deposits or geothermal features.

Temperature and pressure are equally critical. Higher temperatures increase the solubility of minerals in water, expediting the infiltration process. However, extreme heat can also degrade the wood before petrification occurs, creating a delicate balance. Pressure, often from overlying sediment, helps compact the wood and forces minerals into its pores. In deep sedimentary layers, where pressure is higher, petrification can occur more efficiently. Comparative analysis shows that wood buried at depths of 1,000 meters or more petrifies significantly faster than wood near the surface due to increased pressure and mineral availability.

The chemical composition of the surrounding environment also dictates the outcome. Acidic conditions can dissolve wood before it petrifies, while alkaline environments promote mineral precipitation. For example, wood buried in limestone-rich soil, which is alkaline, has a higher chance of successful petrification compared to wood in acidic peat bogs. To maximize petrification potential, avoid burying wood in areas with high organic acid content, such as swamps or decaying vegetation zones.

Finally, the type of wood and its initial state matter. Dense, resinous woods like pine or cedar resist decay longer, providing more time for minerals to infiltrate. Softwoods or decayed wood may disintegrate before petrification completes. Instructive advice: Choose hardwoods with tight grain structures and bury them in environments with optimal mineral content, moderate temperature, and sufficient pressure to enhance the likelihood of successful petrification. By manipulating these environmental conditions, one can influence the timeline and outcome of this ancient process.

Discovering the Lifespan of Wood Ducks: How Long Do They Live?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$6.99

Comparison of wood types in petrification

Petrification, the process by which wood transforms into stone, varies significantly depending on the type of wood involved. Hardwoods like oak and maple, with their dense cell structures, often petrify more slowly than softwoods such as pine or cedar. This is because hardwoods require more time for minerals to permeate their tightly packed cells, typically taking millions of years to fully petrify. Softwoods, with their looser cell arrangements, allow minerals to infiltrate more quickly, reducing the overall petrification time to hundreds of thousands of years. Understanding these differences is crucial for geologists and paleontologists studying fossilized wood.

Consider the practical implications of wood type in petrification for collectors and enthusiasts. If you’re seeking to identify or acquire petrified wood, knowing the original wood type can help estimate its age. For instance, a piece of petrified pine is likely younger than a similarly sized piece of petrified oak, assuming both were buried under similar conditions. Additionally, softwoods often retain more of their original texture and structure during petrification, making them visually distinct from the smoother, more uniform appearance of petrified hardwoods. This knowledge can enhance both the appreciation and valuation of petrified wood specimens.

From a geological perspective, the comparison of wood types in petrification reveals insights into ancient environments. Softwoods, which petrify more rapidly, are often found in younger sedimentary layers, indicating faster burial and mineralization processes. Hardwoods, with their longer petrification timelines, are more commonly associated with older geological formations. By analyzing the wood types in petrified forests, scientists can reconstruct past ecosystems, climate conditions, and even tectonic activity. This comparative approach transforms petrified wood from a mere curiosity into a powerful tool for understanding Earth’s history.

For those interested in the hands-on aspect, experimenting with wood petrification at home can yield fascinating results, though it’s a process that requires patience. Softwoods like balsa or pine can be submerged in a solution of silica-rich water, mimicking natural mineralization, and may show early signs of petrification within a few months. Hardwoods, such as walnut or cherry, will take significantly longer—often years—to exhibit noticeable changes. While this accelerated process doesn’t replicate the millions of years of natural petrification, it offers a tangible way to observe the differential rates at which wood types transform. Always handle chemicals with care and ensure proper ventilation during such experiments.

In conclusion, the comparison of wood types in petrification highlights the interplay between biological structure and geological processes. Whether you’re a scientist, collector, or hobbyist, understanding these differences enriches your engagement with petrified wood. From estimating ages to reconstructing ancient landscapes, the type of wood matters profoundly in the journey from organic material to stone. This knowledge not only deepens appreciation for natural history but also guides practical endeavors, from fieldwork to personal projects.

Treated Wood Drying Time: Factors Affecting the Process and Duration

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Stages of wood petrification process

Petrification is a fascinating process that transforms organic wood into stone-like material over millennia. The journey begins with burial, where wood is quickly covered by sediment, shielding it from oxygen and decay. This initial stage is crucial, as exposure to air would allow microorganisms to decompose the wood entirely. The speed of burial matters—the faster the wood is encased, the better preserved its cellular structure will be for the next stages.

Once buried, the wood enters the permineralization phase, where groundwater rich in minerals like silica, calcite, or pyrite seeps into its pores and cavities. Over time, these minerals crystallize within the wood’s cellular structure, gradually replacing organic matter with inorganic compounds. This stage can take thousands to millions of years, depending on mineral availability and environmental conditions. For example, silica-rich environments, such as ancient volcanic regions, often produce more durable petrified wood.

As permineralization progresses, the wood undergoes fossilization, where organic material is almost entirely replaced by minerals. This stage is marked by the loss of the wood’s original color and texture, though its external shape and internal structure remain intact. The rate of fossilization varies widely; some specimens fossilize in as little as 10,000 years, while others take over 20 million years. Factors like temperature, pressure, and mineral composition play significant roles in determining the timeline.

Finally, exposure occurs when geological processes, such as erosion or tectonic activity, bring the petrified wood to the Earth’s surface. At this stage, the wood is no longer organic but a stone replica, often displaying stunning patterns and colors due to the minerals present. While the entire petrification process typically spans millions of years, each stage is distinct and dependent on specific environmental conditions. Understanding these stages not only highlights the complexity of petrification but also underscores the patience required to witness nature’s transformation of wood into stone.

How Long Does Human Scent Linger in the Woods?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The process of petrification typically takes millions of years, often ranging from 5 to 50 million years, depending on environmental conditions.

Factors include the type of wood, the mineral content of the surrounding water, temperature, pressure, and the presence of silica or other minerals in the environment.

While rare, wood can petrify more quickly (in thousands of years) in environments with high silica concentrations and ideal conditions for mineralization, such as volcanic ash deposits.

Petrification is a specific type of fossilization where organic material is replaced by minerals, preserving the original structure. Not all fossils are petrified.

Yes, larger pieces of wood generally take longer to petrify because minerals need to penetrate and replace more material, whereas smaller pieces may petrify more quickly.