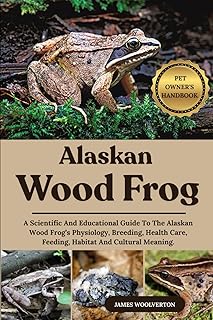

Alaskan wood frogs (Rana sylvatica) are remarkable amphibians known for their ability to survive extreme cold, but their parental care behaviors are equally fascinating. Unlike many frog species that exhibit little to no parental care, Alaskan wood frogs demonstrate a unique level of involvement in their offspring's survival. After laying eggs in shallow pools or wetlands, female wood frogs often remain nearby, providing protection from predators and ensuring the eggs are not disturbed. Additionally, the gelatinous mass surrounding the eggs offers insulation and moisture, aiding in their development. Once the tadpoles hatch, the parental care diminishes, as they rely on their environment and innate behaviors to grow into adulthood. This limited but crucial care during the early stages highlights the adaptive strategies of Alaskan wood frogs in their harsh Arctic habitat.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Parental care duration in Alaskan wood frogs

Alaskan wood frogs (Rana sylvatica) exhibit a unique form of parental care that is both brief and critical for their offspring's survival. Unlike many amphibians, where parental care is minimal or absent, female Alaskan wood frogs demonstrate a specialized behavior known as "oviposition site selection." This involves laying eggs in shallow, ephemeral pools that freeze solid during the winter, a seemingly harsh environment. However, this choice is deliberate: the ice insulates the eggs from extreme cold and predators, creating a safer incubation chamber. This initial act of care is the foundation of their reproductive strategy, but it is just the beginning of a tightly timed process.

The duration of parental care in Alaskan wood frogs is remarkably short, lasting only until the eggs hatch, which typically occurs within 4 to 6 weeks after oviposition. During this period, the female's role is passive yet crucial. She does not actively guard the eggs or provide additional resources, but her choice of oviposition site ensures the eggs' survival through the harsh Alaskan winter. Once the eggs hatch, the tadpoles are left to fend for themselves, relying on the nutrient-rich environment of the thawing pool to grow and develop. This brevity in parental care is a testament to the species' adaptation to extreme environmental conditions, where survival depends on rapid development and minimal energy expenditure.

Comparatively, the parental care duration of Alaskan wood frogs contrasts sharply with that of other amphibians, such as the poison dart frog, which actively transports tadpoles to water-filled bromeliads and feeds them unfertilized eggs. The wood frog's approach is more hands-off, relying on environmental factors rather than direct parental intervention. This difference highlights the diversity of parental care strategies in the animal kingdom and underscores how species evolve unique solutions to common challenges. For Alaskan wood frogs, the key to success lies in timing and the strategic use of their environment.

Understanding the parental care duration of Alaskan wood frogs offers practical insights for conservation efforts. For instance, preserving ephemeral pools—their preferred breeding sites—is essential for maintaining healthy populations. These pools are often threatened by habitat destruction and climate change, which can alter their freezing and thawing cycles. Conservationists can use this knowledge to identify and protect critical breeding habitats, ensuring that the frogs' brief but vital parental care period is not disrupted. By focusing on these specific needs, we can support the survival of this resilient species in an increasingly unpredictable world.

In conclusion, the parental care duration of Alaskan wood frogs is a fascinating example of nature's efficiency. Lasting only until the eggs hatch, this care is characterized by the female's strategic choice of oviposition site rather than active nurturing. This brief yet critical period showcases the species' adaptation to extreme environments and offers valuable lessons for conservation. By studying and protecting their unique reproductive strategy, we can ensure that Alaskan wood frogs continue to thrive in their icy habitats.

Family Dollar Long Wood Narrow Sticks: Uses, Benefits, and Creative Ideas

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Role of parents in offspring survival

Alaskan wood frogs (Rana sylvatica) exhibit a fascinating departure from typical amphibian parenting strategies. Unlike many frog species that abandon eggs after laying, Alaskan wood frogs demonstrate a unique form of parental care. The female frog lays her eggs in shallow pools, often in areas prone to freezing. Here's where the father steps in – he remains with the eggs, providing crucial protection and warmth. This paternal care significantly increases the chances of offspring survival in the harsh Alaskan environment.

The Mechanism of Paternal Care:

The male Alaskan wood frog employs a remarkable strategy to safeguard his offspring. He positions himself over the egg mass, using his body as a shield against predators and insulating the eggs from the extreme cold. This behavior, known as "brooding," can last for several weeks, a substantial investment of time and energy for the father. During this period, he forgoes feeding, relying solely on stored fat reserves.

Impact on Offspring Survival:

The father's dedication pays off. Studies have shown that eggs under paternal care have significantly higher hatching success rates compared to unattended clutches. The father's presence deters predators like beetles and other invertebrates that would readily feast on unprotected eggs. Additionally, his body heat, though minimal, provides a crucial buffer against freezing temperatures, preventing the eggs from succumbing to the harsh Alaskan winters.

A Trade-off for Survival:

This extended period of parental care comes at a cost to the father. The energy expenditure and vulnerability during brooding can leave him weakened and more susceptible to predators himself. However, the evolutionary advantage lies in the increased survival rate of his offspring, ensuring the continuation of his genetic lineage. This trade-off highlights the intricate balance between parental investment and offspring success in the natural world.

Implications for Conservation:

Understanding the role of paternal care in Alaskan wood frog offspring survival has important implications for conservation efforts. Protecting breeding habitats and minimizing disturbances during the critical brooding period are essential for ensuring the long-term viability of this unique species. By safeguarding the fathers and their dedicated care, we ultimately safeguard the future generations of these remarkable amphibians.

Elvis and Anita Wood: Unraveling Their Romantic Relationship Timeline

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Impact of environment on care period

Alaskan wood frogs (Rana sylvatica) are renowned for their remarkable adaptability to extreme environments, but their parental care strategies are notably absent. Unlike many amphibian species, Alaskan wood frogs do not exhibit direct parental care for their offspring. Instead, their reproductive success hinges on environmental factors that influence egg survival and tadpole development. Understanding how the environment impacts this critical period is essential for conservation efforts and ecological studies.

Temperature plays a pivotal role in determining the developmental timeline of Alaskan wood frog offspring. Eggs laid in ephemeral pools or ponds are subject to the surrounding air and water temperatures. In colder environments, such as those found in Alaska, egg development can be significantly prolonged. For instance, eggs may take up to 30 days to hatch in water temperatures below 10°C (50°F), compared to just 7–10 days in warmer conditions around 15°C (59°F). This extended period increases the risk of predation and environmental stressors, underscoring the delicate balance between temperature and survival.

Water availability is another critical environmental factor affecting the care period, albeit indirectly. Alaskan wood frogs often lay their eggs in shallow, temporary water bodies that are prone to drying up. If a pond dries before tadpoles metamorphose into froglets, mortality rates soar. Studies show that tadpoles require at least 6–8 weeks in water to complete metamorphosis. In regions with unpredictable precipitation patterns, such as Alaska’s interior, the timing of egg-laying becomes a high-stakes gamble. Frogs that breed too early or too late in the season risk losing their entire clutch to desiccation.

Predation pressure also shapes the environmental impact on the care period. Eggs and tadpoles are vulnerable to predators like insects, fish, and birds. In environments with high predator density, the survival window narrows, forcing tadpoles to develop faster. For example, in ponds with abundant dragonfly larvae, tadpoles may exhibit accelerated growth rates, completing metamorphosis in as little as 4 weeks. This adaptive response highlights the interplay between environmental threats and developmental strategies.

Conservation efforts must account for these environmental influences to protect Alaskan wood frog populations. Practical steps include preserving ephemeral breeding habitats, monitoring water temperature and quality, and mitigating predation risks through habitat restoration. For enthusiasts or researchers, tracking local weather patterns and water levels can provide valuable insights into optimal breeding times. By addressing these environmental factors, we can ensure that Alaskan wood frogs continue to thrive despite their lack of direct parental care.

Understanding Rick of Wood: Size, Measurement, and Practical Uses

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$11.3 $12.56

Offspring independence timeline in wood frogs

Alaskan wood frogs (Rana sylvatica) exhibit a fascinating reproductive strategy where parental care is minimal, and offspring independence is rapid. Unlike many amphibians, these frogs do not guard eggs or provide direct care to tadpoles. Instead, their survival hinges on rapid development and early independence. The timeline for offspring independence in wood frogs is remarkably short, driven by the harsh Alaskan climate and the need to mature before winter arrives.

The process begins with egg-laying, typically in ephemeral woodland pools or ponds. Eggs hatch within 1 to 3 weeks, depending on temperature, giving rise to tadpoles. These tadpoles must complete metamorphosis within a narrow window—usually 2 to 3 months—to avoid freezing temperatures. During this period, they feed voraciously on algae and organic debris, growing rapidly to reach the critical size needed for transformation into froglets. By late summer, most tadpoles have developed limbs and absorbed their tails, marking the transition to terrestrial life.

Once metamorphosis is complete, young froglets leave the water and disperse into the surrounding forest. At this stage, they are fully independent, relying on their instincts to find food, shelter, and safety. Their diet shifts from herbivorous to carnivorous, primarily consuming small invertebrates like insects and mites. Despite their small size—often less than an inch—these froglets are equipped with the necessary adaptations to survive on their own, including camouflage and the ability to freeze and thaw repeatedly during winter.

The rapid independence of wood frog offspring is a testament to their evolutionary resilience. Unlike species with prolonged parental care, wood frogs prioritize speed and efficiency in development. This strategy ensures that the next generation can survive Alaska’s short summers and long winters. For researchers and enthusiasts, observing this timeline offers insights into how environmental pressures shape reproductive behaviors and life histories in extreme habitats.

Practical tips for studying or conserving wood frogs include monitoring water bodies in early spring for egg masses and tracking tadpole development through regular sampling. Protecting ephemeral pools and maintaining forest connectivity are crucial for supporting their lifecycle. By understanding the offspring independence timeline, conservation efforts can be better tailored to address the unique challenges faced by these remarkable amphibians.

Cigar Longevity in Wooden Boxes: Preservation Tips and Duration Guide

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Parental behavior during early offspring stages

Alaskan wood frogs (Rana sylvatica) exhibit a unique and brief period of parental care, primarily during the early offspring stages. Unlike many other frog species, where parental involvement is minimal or absent, Alaskan wood frogs demonstrate a specialized behavior known as "oviposition site selection." This critical phase occurs immediately after egg-laying and sets the foundation for the offspring's survival. The female carefully chooses a site near water, often in a shallow depression or under vegetation, to deposit her eggs. This strategic placement ensures the eggs remain moist and protected from predators, highlighting the first instance of parental care in these amphibians.

During the early stages of offspring development, the role of the male Alaskan wood frog becomes particularly intriguing. Males often remain near the egg mass, providing a form of passive protection. While they do not actively guard the eggs, their presence may deter potential predators through visual or chemical cues. This behavior is short-lived, typically lasting only a few days, but it underscores the species' nuanced approach to parental care. The male's involvement is a rare example of paternal care in amphibians, making it a fascinating subject for study.

The eggs of Alaskan wood frogs hatch within 10 to 14 days, depending on temperature and environmental conditions. Once the tadpoles emerge, parental care effectively ceases. The tadpoles are left to fend for themselves, relying on their innate instincts to find food and avoid predators. This abrupt end to parental involvement contrasts sharply with the initial care provided during oviposition and the male's brief protective presence. The transition from guarded eggs to independent tadpoles highlights the species' evolutionary strategy, prioritizing early survival over prolonged care.

Understanding the parental behavior of Alaskan wood frogs during the early offspring stages offers valuable insights into amphibian ecology. For conservationists and researchers, this knowledge can inform strategies to protect critical breeding habitats. For instance, preserving areas with suitable oviposition sites—such as wetlands with ample vegetation—can enhance egg survival rates. Additionally, studying this brief but significant parental care period can shed light on the evolutionary trade-offs between parental investment and offspring independence, a dynamic that shapes many species' life histories. By focusing on these early stages, we gain a deeper appreciation for the intricate ways in which Alaskan wood frogs ensure the next generation's survival.

Vinyl vs. Wood Windows: Which Material Offers Longer Durability?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Alaskan wood frogs do not exhibit parental care for their offspring. Once the eggs are laid, the parents do not provide any further care or protection.

No, Alaskan wood frogs do not stay with their eggs after laying them. The female deposits the eggs in water, and both parents leave immediately, leaving the eggs to develop on their own.

Alaskan wood frog tadpoles rely on their instincts and the environment to survive. They feed on algae and organic matter in the water and grow rapidly to avoid predators.

No, Alaskan wood frogs do not show any parental behavior at any stage of their offspring's development. Their reproductive strategy is entirely focused on egg-laying, with no subsequent care.