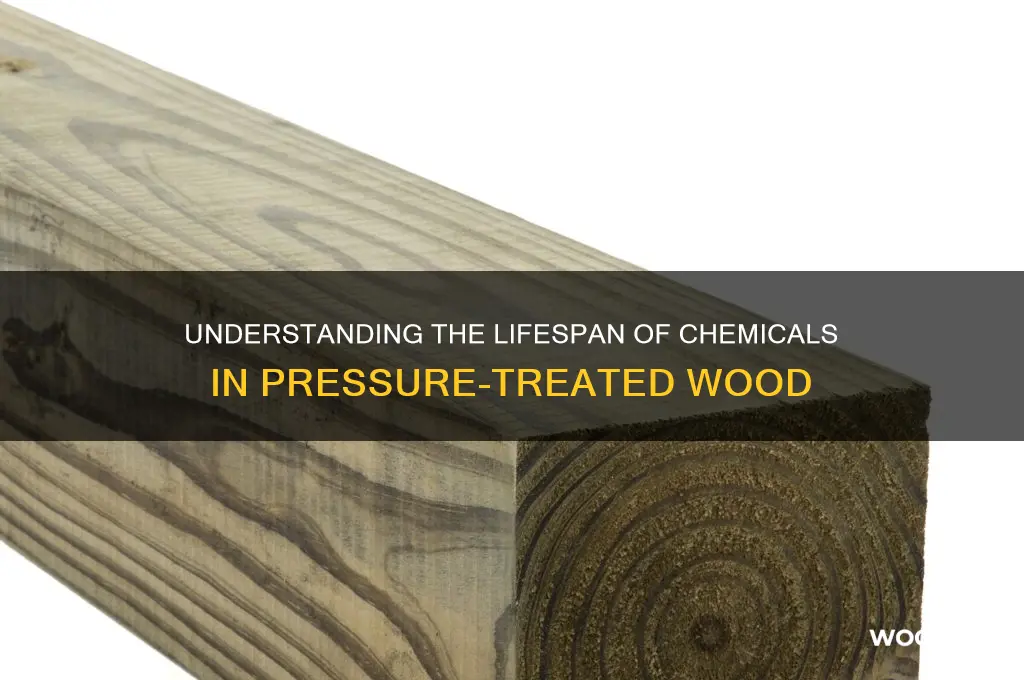

Pressure-treated wood is widely used in construction and outdoor applications due to its enhanced durability and resistance to decay, insects, and moisture. However, the chemicals used in the treatment process, such as alkaline copper quaternary (ACQ), chromated copper arsenate (CCA), or copper azole, raise questions about their longevity within the wood. The retention time of these chemicals depends on factors like the type of preservative, the wood species, environmental exposure, and maintenance practices. Generally, these chemicals are designed to remain effective for decades, often exceeding the wood’s expected lifespan, but gradual leaching can occur over time, particularly in wet or humid conditions. Understanding how long these chemicals stay in pressure-treated wood is crucial for assessing its safety, environmental impact, and suitability for specific applications.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Chemical Retention Time | Varies by treatment type; modern treatments (e.g., ACQ, CA-B) last 20–40+ years |

| Type of Chemicals Used | Common chemicals include ACQ (Alkaline Copper Quaternary), CA-B (Copper Azole), and Micronized Copper |

| Leaching Rate | Minimal leaching over time; <1% of chemicals may leach in the first few years |

| Environmental Factors Affecting Longevity | Moisture, soil contact, and temperature can influence chemical retention |

| Safety After Installation | Safe for general use after proper installation; chemicals are fixed within the wood |

| Biodegradation Resistance | High resistance to decay, insects, and fungal growth due to chemical treatment |

| Regulatory Compliance | Meets standards like AWPA (American Wood Protection Association) for chemical retention |

| Maintenance Requirements | Periodic sealing or staining recommended to extend lifespan and chemical retention |

| Disposal Considerations | Treated wood should be disposed of as hazardous waste in some regions due to chemical content |

| Typical Lifespan of Treated Wood | 20–50+ years depending on use, treatment type, and environmental conditions |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Factors affecting chemical retention in treated wood

The longevity of chemicals in pressure-treated wood is not a fixed timeline but a dynamic interplay of factors that influence retention. Understanding these factors is crucial for predicting the lifespan of treated wood in various applications, from decking to utility poles. One of the primary determinants is the type and concentration of the preservative chemical. For instance, chromated copper arsenate (CCA), once widely used, can remain in wood for decades, while newer alternatives like alkaline copper quaternary (ACQ) and copper azole (CA) may leach more rapidly under certain conditions. The initial chemical dosage, typically measured in pounds per cubic foot (pcf), directly impacts retention—higher concentrations generally equate to longer-lasting protection.

Another critical factor is the wood species and its inherent properties. Dense, low-porosity woods like Douglas fir or southern pine tend to retain chemicals better than lighter, more porous species like spruce or hemlock. The natural extractives in wood, such as resins and tannins, can also interact with preservatives, either enhancing or hindering retention. For example, woods high in lignin often bind copper-based preservatives more effectively, slowing leaching rates. When selecting treated wood, consider the species’ compatibility with the chosen preservative for optimal performance.

Environmental exposure plays a significant role in chemical retention, particularly moisture and temperature fluctuations. Prolonged contact with water, such as in ground-contact applications, accelerates leaching. UV radiation from sunlight can degrade surface chemicals over time, reducing effectiveness. In coastal areas, saltwater exposure poses an additional threat, as chloride ions can displace preservatives from the wood matrix. To mitigate these effects, apply protective coatings or sealants, and ensure proper drainage to minimize moisture retention.

The treatment process itself is a key variable, with factors like pressure, temperature, and duration influencing penetration and fixation. Modern pressure treatment methods, such as the Full-Cell process, ensure deeper chemical penetration compared to older techniques. Vacuum-pressure cycles enhance preservative uptake by removing air from the wood cells, allowing better chemical absorption. Post-treatment handling, including drying and storage conditions, also affects retention—improper drying can lead to chemical migration to the wood surface, reducing interior protection.

Finally, intended use and maintenance dictate how long chemicals remain effective. Ground-contact applications, like fence posts, require higher retention levels and more robust preservatives than above-ground uses, such as decking. Regular inspections and maintenance, such as re-sealing or replacing damaged sections, can extend the wood’s service life. For example, applying a water-repellent sealer annually can reduce moisture absorption and slow chemical leaching. By considering these factors, users can maximize the durability of pressure-treated wood while ensuring safety and environmental compliance.

Drying Fresh Mesquite Wood: Timeframe and Best Practices Explained

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Common chemicals used in pressure treatment

Pressure-treated wood is infused with chemicals to enhance durability, but the longevity of these preservatives varies based on type, application, and environmental factors. Among the most common chemicals used are chromated copper arsenate (CCA), alkaline copper quaternary (ACQ), and copper azole (CA-B). Each has distinct properties and retention periods, influencing how long the wood remains protected against decay, insects, and fungi.

CCA, once the industry standard, contains arsenic, chromium, and copper. While highly effective, its use in residential applications was phased out in 2003 due to health concerns. However, CCA-treated wood installed before this date remains prevalent. Studies show that arsenic can leach from CCA-treated wood over time, with up to 20% of the chemical potentially migrating to the surface within the first decade. To minimize exposure, avoid sanding or burning CCA-treated wood, and seal cut ends with a protective coating.

ACQ, a water-based preservative, relies on copper and a quaternary ammonium compound for protection. It is less toxic than CCA and widely used in decking, fencing, and playground equipment. ACQ-treated wood retains its chemicals for 40+ years in most environments, though copper can migrate to the surface, causing corrosion in metal fasteners. To prevent this, use stainless steel or hot-dipped galvanized hardware. ACQ-treated wood is also prone to surface discoloration, which can be mitigated with a UV-resistant sealant.

Copper azole (CA-B) combines copper and an organic azole compound, offering similar efficacy to ACQ but with reduced leaching. It is commonly used in structural applications like posts and beams. CA-B-treated wood maintains its chemical retention for 30–50 years, depending on moisture exposure. Unlike ACQ, it is less likely to cause corrosion in metal fasteners, making it a preferred choice for load-bearing structures. However, its dark brown color may not appeal to all aesthetic preferences, though staining can help achieve a desired finish.

Understanding the chemicals in pressure-treated wood is crucial for maintenance and safety. For instance, newer treatments like ACQ and CA-B are safer for residential use but require specific care to maximize longevity. Always follow manufacturer guidelines for handling, cutting, and disposing of treated wood. Regular inspections for signs of wear or chemical migration can help ensure the wood remains effective and safe for its intended use.

Epoxy Refill Timing: When to Reapply Epoxy on Wood Surfaces

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Duration of chemical leaching from wood

The duration of chemical leaching from pressure-treated wood varies significantly based on the type of preservative used, environmental conditions, and the wood’s intended application. Chromated copper arsenate (CCA), once the most common treatment, can leach arsenic and chromium into soil for decades, with studies showing detectable levels up to 40 years after installation. Newer treatments like alkaline copper quaternary (ACQ) and copper azole (CA) leach copper at a slower rate, typically stabilizing within 2–5 years, though trace amounts may persist longer in moist environments. Understanding these timelines is critical for assessing environmental impact and safety, particularly in playgrounds, gardens, or areas with high human contact.

Environmental factors play a pivotal role in accelerating or slowing chemical leaching. Rainfall, humidity, and soil pH directly influence how quickly preservatives migrate from the wood. For instance, acidic soils (pH < 5.5) can increase copper leaching from ACQ-treated wood by up to 30%, while arid climates may reduce leaching rates by half compared to humid regions. To mitigate risks, consider using barriers like landscape fabric or gravel beneath treated wood in soil-contact applications. Regularly inspect wood for signs of degradation, as cracked or splintered surfaces can expose fresh preservative to leaching.

For homeowners and builders, choosing the right preservative and application method can minimize leaching concerns. Ground-contact treatments, which contain higher chemical concentrations, are designed to resist leaching but still require careful placement. Above-ground treatments, while lower in chemical dosage, should never be used in soil or water-contact scenarios. If replacing older CCA-treated structures, dispose of the wood properly—many landfills classify CCA-treated wood as hazardous waste. Alternatively, seal cut ends and exposed surfaces with a water-repellent preservative to reduce leaching pathways.

Comparing leaching rates across preservatives highlights the trade-offs between durability and environmental safety. CCA’s long leaching period has led to its phase-out for residential use since 2003, while ACQ and CA offer shorter leaching timelines but may require more frequent maintenance. Micronized copper azole (MCA) treatments, with particle sizes under 1 micron, bond more tightly to wood fibers, reducing leaching by up to 50% compared to standard CA treatments. When selecting treated wood, prioritize products certified by the American Wood Protection Association (AWPA), which adhere to leaching standards and performance benchmarks.

Practical steps can further reduce chemical exposure from treated wood. Avoid using pressure-treated wood for raised garden beds or compost bins unless specifically labeled for food contact. Wash hands after handling treated wood, especially before eating or touching the face. For playgrounds or decks, install a 6-inch layer of mulch or sand beneath the structure to act as a buffer against leached chemicals. Periodic testing of soil around long-standing treated wood structures can identify potential contamination, with remediation options including soil replacement or phytoremediation using hyperaccumulator plants like sunflowers or mustard greens.

Modern Pressure Treated Wood: Enhanced Durability for Longer Lifespan?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Safety concerns and chemical exposure risks

Pressure-treated wood, commonly used in outdoor structures like decks and fences, contains chemicals that can pose health risks if not handled properly. One of the primary concerns is the longevity of these chemicals, which can leach into the environment or come into direct contact with humans and pets. Arsenic, chromium, and copper are among the most common preservatives used, and their persistence varies depending on the type of treatment and environmental conditions. For instance, chromated copper arsenate (CCA), once widely used, can remain in wood for decades, while newer alternatives like alkaline copper quaternary (ACQ) may leach more rapidly but are considered less toxic. Understanding these differences is crucial for assessing exposure risks.

For homeowners and DIY enthusiasts, direct contact with pressure-treated wood during installation or maintenance is a significant concern. Sawing, sanding, or burning treated wood releases toxic particles into the air, which can be inhaled or settle on skin and clothing. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) recommends wearing gloves, long sleeves, and a dust mask when working with treated wood, and thoroughly washing exposed skin and clothing afterward. Children and pets are particularly vulnerable due to their tendency to play near treated structures and their higher susceptibility to chemical absorption. Avoiding direct contact with treated surfaces, such as using barriers or sealants, can mitigate these risks.

Leaching of chemicals into soil and water is another critical issue, especially in areas with high moisture or rainfall. Studies show that CCA-treated wood can release arsenic into the surrounding soil at levels exceeding safe thresholds for gardens or playgrounds. To minimize environmental contamination, the EPA advises against using pressure-treated wood for structures in direct contact with soil or water, such as garden beds or waterfront docks. Instead, consider alternative materials like naturally rot-resistant wood (e.g., cedar or redwood) or non-wood options like composite lumber, which do not contain harmful preservatives.

Long-term exposure to chemicals in pressure-treated wood has been linked to health issues, including skin irritation, respiratory problems, and in severe cases, cancer. Arsenic, in particular, is a known carcinogen, and prolonged exposure through ingestion or inhalation can pose serious risks. For example, children playing on CCA-treated playground equipment have been found to have higher arsenic levels in their urine. Regularly inspecting treated wood for signs of deterioration, such as cracking or splintering, and replacing damaged sections promptly can reduce exposure. Additionally, sealing treated wood with a water-repellent product can help minimize leaching and extend its lifespan.

In conclusion, while pressure-treated wood offers durability and resistance to decay, its chemical content demands careful consideration. By understanding the type of treatment used, following safety guidelines during handling, and choosing appropriate applications, individuals can balance the benefits of treated wood with the need to protect health and the environment. For those seeking safer alternatives, exploring non-toxic materials or newer, less hazardous preservatives can provide peace of mind without compromising structural integrity.

Italian Wood Aging Secrets: Unveiling the Timeless Craft of Master Luthiers

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Methods to prolong chemical effectiveness in treated wood

The lifespan of chemicals in pressure-treated wood typically ranges from 10 to 40 years, depending on factors like wood type, chemical formulation, and environmental exposure. Prolonging their effectiveness requires strategic interventions that minimize leaching, degradation, and environmental wear. Here’s how to maximize their longevity.

Sealants and Coatings: The First Line of Defense

Applying a high-quality sealant or exterior-grade paint creates a physical barrier that shields treated wood from moisture, UV rays, and microbial activity—all of which accelerate chemical breakdown. Use a water-repellent sealer with UV inhibitors for optimal protection. Reapply every 2–3 years, especially in humid or sun-exposed areas. For structural elements like deck posts, consider a thicker epoxy-based coating, which bonds deeply into the wood grain, reducing water absorption by up to 90%.

Strategic Placement and Design: Engineering for Longevity

Position treated wood components to minimize ground contact and water pooling. Elevate structures using concrete footings or gravel beds to reduce soil-borne moisture exposure. Incorporate design features like slatted decking or angled surfaces to encourage water runoff. For example, a 1:20 slope on decks prevents standing water, cutting moisture-related chemical leaching by nearly 50%. Pair this with regular inspections to identify and replace compromised sections before they undermine the entire structure.

Periodic Re-Treatment: Reinforcing Chemical Barriers

While pressure-treated wood cannot be re-treated in the same industrial manner, surface-applied preservatives like copper naphthenate (at a concentration of 1–2% solution) can replenish lost chemicals. Apply these treatments every 5–7 years, focusing on end grains and cut surfaces where chemicals leach most rapidly. Always wear protective gear, as these solutions are toxic upon direct contact. Note: This method is most effective for non-load-bearing elements like fence pickets or garden beds.

Environmental Management: Controlling External Threats

Reduce chemical degradation by managing the wood’s surroundings. Install gutters and downspouts to divert rainwater away from structures. In coastal regions, use sacrificial flashings made of zinc or aluminum to absorb corrosive salts before they reach the wood. For ground-contact applications, lay a geotextile barrier between soil and wood to minimize fungal growth. Studies show these measures can extend chemical retention by 30–40% in high-risk environments.

By combining these methods—sealants, smart design, re-treatment, and environmental control—you can significantly prolong the effectiveness of chemicals in treated wood, ensuring decades of structural integrity and reduced maintenance.

Drying Wood Post-Rain: Understanding the Timeframe for Optimal Results

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The chemicals in pressure treated wood can remain active for 20 to 40 years or more, depending on the type of treatment and environmental conditions.

Yes, some chemicals can leach out over time, especially in the first few years after treatment, but the majority remain bound within the wood fibers.

Yes, once the chemicals have stabilized (usually within 6 to 12 months), pressure treated wood is considered safe for most applications, including outdoor structures and garden beds.

Exposure to moisture, sunlight, and temperature fluctuations can accelerate the breakdown of chemicals, but modern treatments are designed to withstand harsh weather conditions for decades.

Yes, pressure treated wood can often be reused or recycled, but it should be handled with care and disposed of properly to avoid environmental contamination.