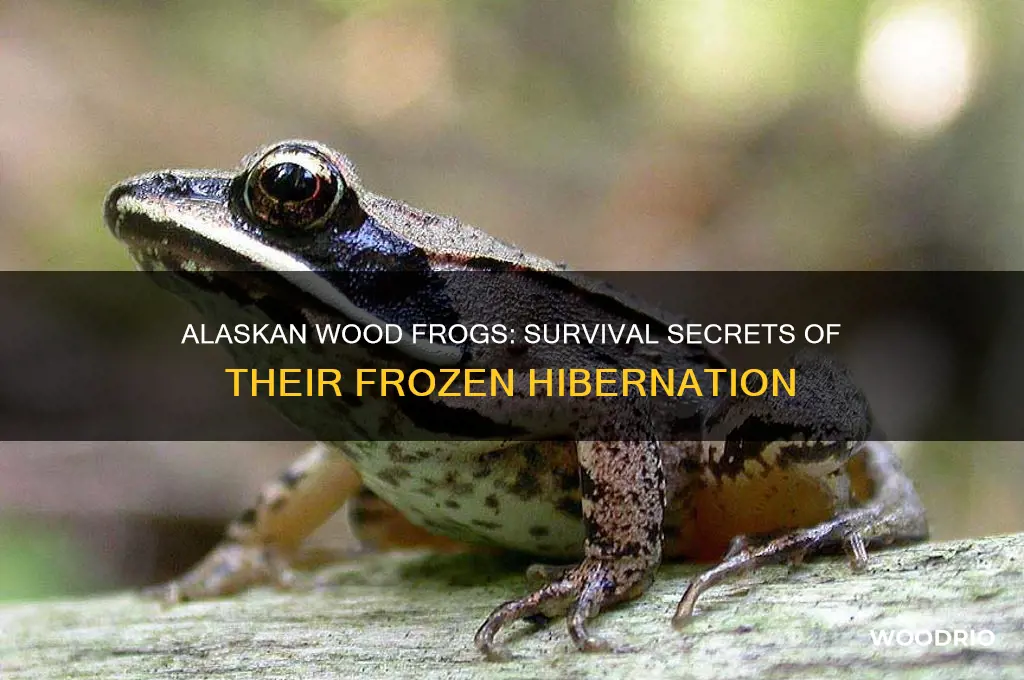

Alaskan wood frogs (Rana sylvatica) are remarkable creatures known for their extraordinary ability to survive freezing temperatures by entering a state of cryopreservation. During the harsh Alaskan winters, these frogs can remain frozen for up to seven months, with their bodies reaching ice concentrations of up to 70%. This survival mechanism involves the production of glucose, which acts as a natural antifreeze, preventing ice crystals from forming in vital organs. Despite their heart and brain activity ceasing, they revive once temperatures rise in spring, showcasing one of nature's most fascinating adaptations to extreme environments.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Duration of Frozen State | Up to 7 months (entire winter season) |

| Survival Mechanism | Glycerol production to protect cells from freezing damage |

| Body Water Frozen | Up to 70% of body water turns to ice |

| Heart and Brain Activity | Stops completely during freezing |

| Resumption of Vital Functions | Gradually resumes upon thawing in spring |

| Geographic Range | Interior Alaska and other cold regions |

| Scientific Name | Rana sylvatica (Alaskan wood frog) |

| Metabolic Rate During Freezing | Reduced to nearly undetectable levels |

| Critical Temperature for Freezing | Below -8°C (18°F) |

| Energy Source During Frozen State | Stored glycogen and minimal metabolic activity |

| Thawing Process | Gradual warming as temperatures rise above freezing |

| Survival Success Rate | High, with most individuals surviving multiple winters |

| Adaptations for Freezing | Specialized proteins and glucose to prevent cell collapse |

| Active Season | Spring to fall (after thawing) |

| Research Significance | Model organism for studying cryopreservation and extreme survival |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Freeze Tolerance Mechanisms: How Alaskan wood frogs survive freezing temperatures without cellular damage

- Duration of Frozen State: Average time Alaskan wood frogs remain frozen during winter months

- Seasonal Timing: When Alaskan wood frogs freeze and thaw in their annual cycle

- Survival Adaptations: Physiological changes enabling Alaskan wood frogs to endure freezing

- Environmental Factors: How temperature and habitat influence Alaskan wood frogs' freezing duration

Freeze Tolerance Mechanisms: How Alaskan wood frogs survive freezing temperatures without cellular damage

Alaskan wood frogs (Rana sylvatica) can survive being frozen for up to 7 months, enduring temperatures as low as -16°C (3°F) without suffering cellular damage. This extraordinary feat is made possible through a suite of freeze tolerance mechanisms that have evolved over millennia. Unlike freeze-avoidant species, which prevent ice formation entirely, these frogs allow ice crystals to form in their extracellular spaces while protecting their cells from damage. The process begins with the frog’s recognition of subzero temperatures, triggering a cascade of physiological responses that ensure survival.

One key mechanism is the production of cryoprotectants, specifically glucose and glycerol, which accumulate in the frog’s tissues. These substances act like antifreeze, lowering the freezing point of bodily fluids and preventing ice crystals from forming inside cells, where they would otherwise rupture membranes and destroy vital structures. Glucose levels can increase from a normal 2–4 millimoles per liter to 200–300 millimoles per liter during freezing, providing critical protection. Glycerol, synthesized in the liver, is distributed throughout the body, further stabilizing cell membranes and reducing osmotic stress.

Equally important is the frog’s ability to dehydrate its cells. As ice forms in the extracellular space, water is drawn out of cells via osmosis, concentrating intracellular fluids and minimizing the risk of ice crystal formation within the cell itself. This dehydration is carefully regulated to avoid damaging cellular proteins and enzymes. Simultaneously, the frog’s heart and brain functions cease, and its metabolism slows to nearly undetectable levels, conserving energy and reducing the need for oxygen.

To prevent tissue damage upon thawing, Alaskan wood frogs employ antifreeze proteins that inhibit the growth of ice crystals, ensuring they remain small and non-lethal. These proteins bind to ice crystals as they form, preventing them from growing large enough to puncture cell membranes. Additionally, the frogs’ cells express heat shock proteins, which repair any minor damage that occurs during freezing or thawing, maintaining cellular integrity.

Practical observations of this process reveal that the frogs often freeze in shallow depressions under leaf litter or snow, where temperatures are stable but not extreme. Thawing typically occurs gradually in early spring, allowing the frogs to rehydrate and resume normal physiological functions. For those studying or observing these frogs, it’s crucial to avoid rapid temperature changes, as this can cause fatal tissue damage. Instead, gradual warming over 12–24 hours mimics natural conditions and ensures the frog’s survival. Understanding these mechanisms not only highlights the ingenuity of nature but also offers insights into cryopreservation techniques for medical and scientific applications.

Understanding Morning Wood: Duration and Factors Affecting Its Disappearance

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Duration of Frozen State: Average time Alaskan wood frogs remain frozen during winter months

Alaskan wood frogs (Rana sylvatica) are marvels of adaptation, capable of surviving temperatures that would be lethal to most other amphibians. During the harsh Alaskan winters, these frogs enter a state of cryopreservation, where up to 70% of their body water freezes. The duration of this frozen state is a critical aspect of their survival strategy, and research indicates that they typically remain frozen for 5 to 7 months, depending on the severity of the winter and the timing of spring thaw. This period is not arbitrary; it is finely tuned to the environmental cues of their habitat, ensuring they reanimate when conditions are favorable for feeding and reproduction.

To understand this phenomenon, consider the physiological mechanisms at play. Alaskan wood frogs produce high concentrations of glucose, which acts as a natural antifreeze, preventing ice crystals from forming in vital organs. This process allows them to endure subzero temperatures for extended periods. Interestingly, the timing of freezing and thawing is not uniform across all individuals. Younger frogs, for instance, may freeze earlier and thaw later than adults, as their smaller body mass makes them more susceptible to temperature fluctuations. This variability highlights the species’ adaptability and the importance of age-specific survival strategies.

From a practical standpoint, understanding the duration of their frozen state has implications for conservation efforts. Climate change poses a threat to this delicate balance, as warmer winters may disrupt the frogs’ freezing and thawing cycles. For example, premature thawing could expose them to predators or energy depletion before food sources become available. Conservationists can use this knowledge to monitor populations and implement protective measures, such as preserving wetland habitats that provide insulation during freezing periods.

Comparatively, the Alaskan wood frog’s ability to remain frozen for months outstrips that of other freeze-tolerant species, such as the gray treefrog, which typically freezes for shorter durations. This extended freeze tolerance is a testament to the Alaskan wood frog’s evolutionary specialization to its extreme environment. By studying these frogs, scientists gain insights into cryobiology, which could have applications in fields like organ preservation and agriculture.

In conclusion, the average time Alaskan wood frogs remain frozen—5 to 7 months—is a remarkable adaptation shaped by their environment and physiology. This duration is not just a biological curiosity but a critical survival mechanism with broader implications for science and conservation. By appreciating the specifics of their frozen state, we can better protect these resilient amphibians and the ecosystems they inhabit.

Understanding FF Wood Biscuit Sizes and Their Standard Lengths

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Seasonal Timing: When Alaskan wood frogs freeze and thaw in their annual cycle

Alaskan wood frogs (Rana sylvatica) are marvels of adaptation, capable of surviving temperatures that would be lethal to most other amphibians. Their annual cycle includes a dramatic freeze-thaw process, timed precisely to coincide with Alaska’s harsh winters and brief summers. This seasonal timing is not random but a finely tuned strategy to endure extreme cold while maximizing reproductive opportunities. Understanding when and why they freeze and thaw offers insight into their remarkable resilience.

The freezing process begins in late fall, typically between October and November, as temperatures drop below freezing. As ice crystals form in their surroundings, Alaskan wood frogs respond by gradually increasing the concentration of glucose in their blood, acting as a natural antifreeze. This process, known as cryoprotection, prevents ice from forming inside their cells, which would otherwise rupture and kill them. By mid-winter, these frogs are fully frozen, their hearts stopped, and their brains inactive. Remarkably, they remain in this state for approximately 7 to 9 months, depending on the severity of the winter and the timing of spring thaw.

Thawing occurs in spring, usually between April and May, as temperatures rise above freezing. This is a critical and vulnerable period for the frogs. Thawing must happen slowly and naturally, as rapid rewarming can cause tissue damage. Once thawed, the frogs quickly resume their metabolic activities, including breathing, circulation, and movement. This timing is crucial, as it allows them to emerge just as their breeding habitats—shallow woodland pools—are melting and becoming accessible. The frogs then have a narrow window, typically 1 to 2 weeks, to mate and lay eggs before the pools dry up or freeze again.

Practical observations of this cycle highlight the importance of environmental cues. For instance, frogs in northern Alaska, where winters are longer and colder, may remain frozen for up to 9 months, while those in milder southern regions thaw earlier. Conservation efforts must consider these timing patterns, as disruptions caused by climate change—such as earlier thaws or unpredictable temperature fluctuations—could desynchronize the frogs’ life cycle, threatening their survival. Monitoring these seasonal shifts is essential for protecting this unique species.

In summary, the seasonal timing of Alaskan wood frogs’ freeze-thaw cycle is a delicate balance of survival and reproduction. From their fall freeze to their spring thaw, every stage is synchronized with Alaska’s extreme climate. This precision ensures their longevity but also makes them vulnerable to environmental changes. By studying this cycle, we gain not only a deeper appreciation for their adaptability but also valuable insights into the broader impacts of climate variability on wildlife.

Understanding Standard Lengths of 1-Inch Thick Wood Planks

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$11.3 $12.56

Survival Adaptations: Physiological changes enabling Alaskan wood frogs to endure freezing

Alaskan wood frogs (Rana sylvatica) can survive being frozen for up to 7 months, enduring temperatures as low as -8°C (17.6°F) during Alaska’s harsh winters. This extraordinary feat is made possible through a series of precise physiological adaptations that transform their bodies into a state of suspended animation. Unlike organisms that succumb to ice crystal damage, these frogs actively control the freezing process, ensuring their cells remain intact. The key lies in their ability to replace nearly 70% of their body’s water with glucose, a natural cryoprotectant that lowers the freezing point of their tissues and prevents lethal ice formation in vital organs.

To initiate this process, Alaskan wood frogs undergo a strategic dehydration, drawing water out of cells and into the bloodstream, where it can safely freeze without rupturing membranes. Simultaneously, their livers ramp up glucose production, flooding the body with concentrations up to 20 times higher than normal. This glucose acts as both an antifreeze and an energy reserve, allowing the frog to maintain minimal metabolic functions while frozen. Remarkably, their heart stops beating, brain activity ceases, and 95% of their body water turns to ice, yet they remain poised to revive when temperatures rise.

One of the most critical adaptations is the redistribution of ice within the body. Alaskan wood frogs ensure that ice forms in the body cavity and between tissues rather than inside cells, where it would be fatal. Specialized proteins and nucleating agents in their skin and muscles act as ice-crystal managers, controlling the size and location of ice formation. This precision prevents mechanical damage to organs and preserves the integrity of cellular structures. Upon thawing, the frogs’ bodies rehydrate cells, restart circulation, and resume normal functions within 10 to 14 days, a process as methodical as it is miraculous.

For those studying or observing these frogs in the wild, understanding their freezing timeline is crucial. Alaskan wood frogs typically freeze in October as temperatures drop and thaw in April or May, depending on local conditions. Researchers often track glucose levels in their tissues as a marker of freezing preparedness, noting that levels peak just before ice crystallization begins. Practical tips for conservationists include monitoring wetland habitats—critical for their survival—and avoiding disturbances during their frozen state, as even minor disruptions can compromise their delicate physiological balance.

In comparison to other freeze-tolerant species, Alaskan wood frogs stand out for their ability to survive longer and under more extreme conditions. While some insects or reptiles can endure brief freezing, the wood frog’s multi-month hibernation showcases a more sophisticated adaptation. This makes them a prime subject for biomimicry research, particularly in cryopreservation techniques for human organs or food storage. By studying their glucose-based strategy, scientists hope to unlock new methods for preserving tissues without damage, bridging the gap between nature’s ingenuity and human innovation.

Durability of Charred Wood: Longevity and Preservation Techniques Explained

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Environmental Factors: How temperature and habitat influence Alaskan wood frogs' freezing duration

Alaskan wood frogs (Rana sylvatica) can survive being frozen for up to 7 months, a remarkable adaptation to their harsh environment. This survival mechanism hinges critically on environmental factors, particularly temperature and habitat, which dictate the duration and success of their frozen state. Understanding these factors not only sheds light on the frog’s resilience but also offers insights into cryopreservation techniques for other organisms.

Temperature plays a dual role in the freezing process of Alaskan wood frogs. When temperatures drop below -2°C (28°F), the frogs begin to freeze, with ice crystals forming in their body cavities and under their skin. However, their core organs remain ice-free due to high concentrations of glucose, which acts as a natural cryoprotectant. The rate of freezing is crucial: gradual cooling allows the frogs to adjust their physiology, while rapid freezing can be lethal. For instance, frogs in habitats with consistent, slow temperature declines, such as shaded forests, fare better than those in open areas with fluctuating temperatures. Once frozen, the duration of their suspended state depends on how long temperatures remain below freezing. Prolonged subzero conditions, common in Alaska’s interior, can keep frogs frozen for the entire winter, while milder coastal climates may shorten this period.

Habitat quality significantly influences the frogs’ ability to endure freezing. Moist, well-drained soils rich in organic matter provide ideal hibernation sites, as they insulate the frogs from extreme temperature fluctuations and prevent desiccation. In contrast, dry or compacted soils can expose frogs to lethal freezing conditions or dehydration. Vegetation cover also matters: leaf litter and moss act as thermal buffers, moderating temperature changes and protecting frogs from predators. Interestingly, frogs in habitats with access to both open water and dense vegetation have higher survival rates, as these areas offer both breeding grounds and safe hibernation sites.

To maximize survival, Alaskan wood frogs employ a strategic combination of behavioral and physiological adaptations. They seek out hibernation sites in late fall, often burrowing into the forest floor or beneath logs. During this time, their metabolism slows to nearly 0%, and their heart and brain activity cease entirely. Thawing occurs in spring when temperatures rise above 0°C (32°F), but even then, the process must be gradual to avoid tissue damage. Conservation efforts should focus on preserving diverse habitats with ample vegetation and moisture, as these are critical for the frogs’ long-term survival.

In practical terms, understanding these environmental factors can inform conservation strategies and even medical research. For example, studying how glucose protects Alaskan wood frogs from ice damage could inspire new cryopreservation methods for human organs. Similarly, habitat restoration projects could prioritize creating microclimates that mimic the frogs’ natural hibernation sites, ensuring their populations remain resilient in the face of climate change. By safeguarding the delicate balance of temperature and habitat, we can help these extraordinary amphibians continue to thrive in one of the world’s most extreme environments.

From Forest to Factory: Crafting Long Wooden Planks Explained

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Alaskan wood frogs can stay frozen for up to 7 months, typically during the harsh winter months.

Yes, up to 70% of their body, including vital organs, can freeze solid, while their blood and other fluids contain high levels of glucose to prevent ice crystal damage.

They produce high levels of glucose, which acts as a natural antifreeze, and their metabolism slows dramatically to conserve energy during freezing.

Once temperatures rise, their hearts begin to beat again, and they slowly resume normal bodily functions, typically within 10-14 days after thawing.