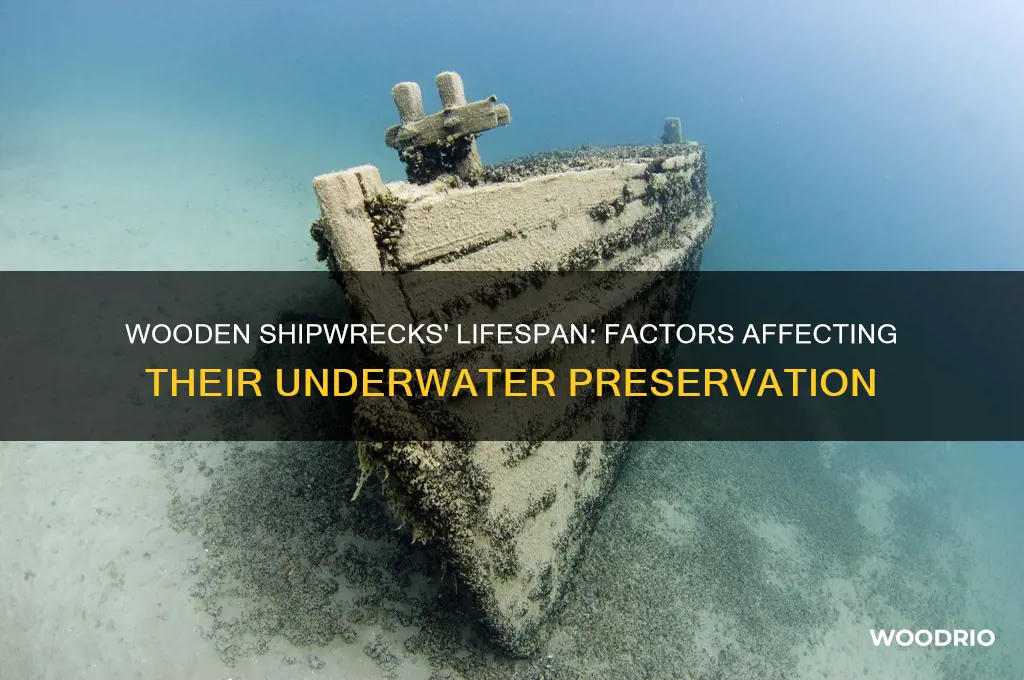

Wooden shipwrecks, submerged beneath the ocean's surface, face a complex interplay of factors that determine their longevity. While wood is inherently biodegradable, the unique conditions of the underwater environment can significantly slow down decomposition. Anaerobic conditions, low oxygen levels, and cold temperatures in deeper waters can preserve wooden structures for centuries, even millennia. However, factors like salinity, marine organisms, and human activity can accelerate deterioration. Understanding the lifespan of wooden shipwrecks is crucial for archaeological preservation, as these remnants offer invaluable insights into maritime history, trade routes, and shipbuilding techniques.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Preservation in Anaerobic Environments (e.g., deep water, sediment) | Can last hundreds to thousands of years due to lack of oxygen, which slows degradation. |

| Preservation in Cold Water | Cold temperatures slow biological activity, extending lifespan to centuries. |

| Burial in Sediment | Sediment protects wood from erosion, biological attack, and UV radiation, preserving shipwrecks for millennia. |

| Type of Wood | Harder woods (e.g., oak) last longer than softer woods (e.g., pine). |

| Biological Activity | Shipworms (Teredo worms) and fungi can rapidly degrade wood in warm, shallow waters, reducing lifespan to decades. |

| Salinity of Water | High salinity can accelerate wood degradation, while freshwater environments may preserve wood better. |

| Depth of Water | Deeper waters (below the photic zone) reduce exposure to light, temperature fluctuations, and biological activity, extending lifespan. |

| Human Activity | Salvage, looting, and fishing activities can accelerate deterioration. |

| Exposure to Weather and Waves | Shallow-water shipwrecks exposed to waves and storms degrade faster than those in sheltered or deep locations. |

| Chemical Composition of Water | Acidic or polluted water can accelerate wood decay, while alkaline water may preserve it better. |

| Examples of Longevity | The Mary Rose (1545) and Vasa (1628) have survived for centuries due to preservation efforts and environmental conditions. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Factors affecting wood decay underwater

Wooden shipwrecks submerged underwater face a complex interplay of factors that determine their longevity. One critical element is the type of wood itself. Dense, resinous woods like oak or teak naturally resist decay due to their high tannin content, which deters marine borers and fungi. In contrast, softer woods like pine or cedar degrade more rapidly unless treated with preservatives. For instance, the Vasa, a 17th-century Swedish warship, survived centuries in the Baltic Sea due to its oak construction and the cold, low-oxygen environment.

Water chemistry plays a pivotal role in wood decay. Salinity levels directly influence the activity of wood-boring organisms like teredo worms, which thrive in saltwater but struggle in freshwater. pH levels also matter; acidic waters accelerate decay by weakening cellulose fibers, while alkaline conditions can slow it. Temperature is another key factor—colder waters, like those in the Arctic or deep ocean, preserve wood by slowing microbial activity. Warmer tropical waters, however, foster rapid decay due to increased biological activity.

The depth and sedimentation of the shipwreck site significantly impact preservation. Deeper waters often lack oxygen, creating anaerobic conditions that inhibit aerobic bacteria and fungi responsible for wood decay. Sediment burial acts as a protective layer, shielding wood from destructive organisms and UV radiation. For example, the Mary Rose, Henry VIII’s flagship, was preserved in the silty seabed of the Solent for over 400 years. Conversely, exposed wrecks in shallow, turbulent waters degrade faster due to constant abrasion and biological attack.

Human intervention can both preserve and accelerate decay. Salvage operations often disrupt protective sediment layers, exposing wood to destructive elements. Conservation efforts, such as applying polyethylene glycol (PEG) to replace lost cellulose, have successfully stabilized shipwrecks like the Vasa. However, improper handling or storage can introduce contaminants that hasten deterioration. For enthusiasts or archaeologists, documenting site conditions and minimizing disturbance are essential steps to ensure long-term preservation.

Understanding these factors allows for better prediction and management of wooden shipwrecks’ lifespans. By controlling what can be controlled—such as storage conditions or conservation treatments—and respecting what cannot, like natural water chemistry, we can safeguard these historical treasures for future generations. Whether through scientific research or careful stewardship, the fate of underwater wooden relics lies in our hands.

Durability of Wooden Groynes: Lifespan and Coastal Protection Insights

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Role of sediment burial in preservation

Sediment burial acts as a time capsule for wooden shipwrecks, shielding them from the destructive forces of oxygen, sunlight, and marine organisms. When a wreck becomes buried under layers of sand, silt, or mud, it enters an anaerobic environment where the lack of oxygen slows the decay process. This natural preservation method has allowed some ships to endure for centuries, their wooden structures remarkably intact. For instance, the 16th-century vessel *Mary Rose* in England survived due to sediment burial, with its hull and artifacts preserved in a state that offers unparalleled insights into Tudor maritime life.

The effectiveness of sediment burial depends on the type and rate of sedimentation. Fine-grained sediments like silt and clay provide better protection than coarse sands, as they create a denser barrier against water flow and oxygen infiltration. In areas with high sedimentation rates, such as river deltas or sheltered bays, shipwrecks are more likely to be quickly and completely buried. However, too rapid burial can sometimes compress the wreck, causing structural damage. Ideal conditions involve a gradual accumulation of sediment, allowing the wreck to settle without undue stress.

While sediment burial is a powerful preservative force, it is not without risks. Buried wrecks can still degrade if the sediment layer shifts or erodes, exposing the wood to harmful elements. Additionally, certain anaerobic bacteria can thrive in buried environments, producing acids that weaken wooden structures over time. Conservationists often monitor sediment-buried sites, using techniques like core sampling and sonar surveys to assess the stability of the burial layer and the condition of the wreck beneath.

For those seeking to preserve wooden shipwrecks, understanding sediment dynamics is crucial. Practical steps include identifying low-energy environments where sedimentation is likely to occur naturally, such as deep-water basins or areas with minimal wave action. In some cases, artificial sedimentation—the controlled deposition of sand or silt—can be employed to protect exposed wrecks. However, this approach requires careful planning to avoid damaging the site. By harnessing the protective power of sediment burial, we can ensure that these maritime relics endure for future generations, offering windows into history that might otherwise be lost.

Woodpecker Lifespan: Understanding How Long These Birds Typically Live

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Impact of marine organisms on wreckage

Wooden shipwrecks submerged in marine environments face relentless assault from a diverse array of organisms, each contributing uniquely to their degradation. Among the most notorious are shipworms, marine bivalve mollusks that bore into wood, digesting cellulose and leaving behind a honeycomb of tunnels. A single shipworm can penetrate up to 20 centimeters of wood annually, significantly weakening structural integrity. In tropical waters, where shipworm activity is highest, wooden wreckage can disintegrate within a decade if left unprotected. This rapid decay underscores the critical role of these organisms in determining the lifespan of submerged timber.

Beyond shipworms, microbial communities play a silent but equally destructive role. Bacteria and fungi colonize wood surfaces, secreting enzymes that break down lignin and cellulose, the primary components of wood. In anaerobic conditions, sulfate-reducing bacteria produce hydrogen sulfide, which accelerates corrosion of any metal fasteners, further destabilizing the wreckage. Studies show that in nutrient-rich environments, such as coastal areas with high organic runoff, microbial degradation can reduce wood strength by 50% within five years. To mitigate this, conservationists often treat recovered wood with polyethylene glycol (PEG) to replace lost cellulose and stabilize the material.

Coralline organisms, while less directly destructive, contribute to the demise of wooden shipwrecks by encrusting surfaces and altering their structural dynamics. Barnacles, sponges, and corals attach to wood, increasing drag and exposing it to greater mechanical stress from currents. Over time, this biofouling can cause wood to crack or splinter, particularly in areas of repeated stress. For instance, a 19th-century shipwreck in the Mediterranean exhibited fractures along barnacle-encrusted joints, highlighting how seemingly benign organisms can exacerbate physical deterioration. Regular cleaning and controlled removal of biofouling are essential to preserving exposed wreckage.

The interplay between marine organisms and environmental factors further complicates the preservation of wooden shipwrecks. In colder, deeper waters with lower oxygen levels, degradation slows significantly, as both shipworm activity and microbial metabolism are inhibited. For example, the Vasa, a 17th-century Swedish warship salvaged from the Baltic Sea, retained much of its structure due to the region’s cold, brackish conditions. Conversely, shipwrecks in warm, shallow waters, such as the Caribbean, often vanish within decades. This contrast illustrates the importance of site-specific conditions in predicting wreckage longevity and designing conservation strategies.

To combat the impact of marine organisms, proactive measures are essential. For in-situ preservation, encapsulating wreckage in geotextile fabrics can deter shipworm infestation and reduce biofouling. Alternatively, relocating artifacts to controlled environments, such as freshwater baths or climate-controlled museums, halts biological activity entirely. However, such interventions are costly and require ongoing maintenance. For enthusiasts and archaeologists, monitoring water chemistry, temperature, and biological activity at shipwreck sites provides critical data for predicting degradation rates and tailoring preservation efforts. Understanding these organism-driven processes is key to safeguarding maritime heritage for future generations.

Exploring Muir Woods: Ideal Time to Spend Among the Redwoods

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Preservation techniques for wooden shipwrecks

Wooden shipwrecks, when submerged in the right conditions, can endure for centuries, but their preservation is far from guaranteed. The key to their longevity lies in the environment and the techniques employed to protect them. One of the most critical factors is the water’s chemistry: anaerobic, cold, and low-salinity conditions slow the growth of shipworm and other wood-boring organisms, naturally preserving the wreck. For instance, the *Vasa*, a 17th-century Swedish warship, survived remarkably well in the cold, brackish waters of Stockholm’s harbor, where low oxygen levels inhibited decay. However, once exposed to air or different water conditions, wooden wrecks rapidly deteriorate, making preservation techniques essential.

One effective preservation method is in situ conservation, which involves leaving the shipwreck in its original location while implementing protective measures. This approach minimizes disturbance and maintains the site’s historical context. Techniques include covering the wreck with sand or geotextile fabrics to shield it from currents and sedimentation, or installing sacrificial anodes to prevent corrosion of metal artifacts. For example, the *Mary Rose*, Henry VIII’s flagship, was protected by a layer of silt that preserved its wooden hull for over 400 years. However, in situ preservation requires ongoing monitoring and is not feasible in all environments, particularly where water conditions are unfavorable.

When in situ preservation is not possible, ex situ methods become necessary. This involves raising the shipwreck or its components for treatment and display. The process begins with desalination to remove salts that cause swelling and cracking in wood. This is typically done by soaking the wood in freshwater baths, gradually increasing the concentration of polyethylene glycol (PEG), a preservative that replaces water in the wood’s cellular structure. The *Vasa* underwent this treatment for over two decades, with PEG concentrations reaching 75% to stabilize its timber. After treatment, the wood must be stored in a controlled environment to prevent further degradation.

Another innovative technique is 3D scanning and digital preservation, which creates detailed models of shipwrecks for research and public engagement without physical intervention. This non-invasive method is particularly valuable for sites at risk of collapse or inaccessibility. For instance, the *Antikythera Shipwreck* in Greece, known for its ancient astronomical mechanism, has been digitally mapped to study its structure and artifacts remotely. While digital preservation does not protect the physical wreck, it ensures its legacy endures for future generations.

Ultimately, the choice of preservation technique depends on the wreck’s condition, location, and cultural significance. While some methods, like in situ conservation, aim to preserve the shipwreck in its original state, others, like ex situ treatment, prioritize accessibility and long-term stability. Each approach has its challenges, from the logistical complexities of raising a wreck to the ethical considerations of altering its historical context. By combining traditional conservation methods with modern technology, we can ensure that wooden shipwrecks continue to reveal their secrets for centuries to come.

Secret Wood Wings Durability: Lifespan and Longevity Explained

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Examples of long-lasting wooden shipwrecks globally

Wooden shipwrecks, when submerged in the right conditions, can endure for centuries, offering a glimpse into maritime history. One remarkable example is the Mary Rose, Henry VIII’s flagship, which sank in 1545 off the coast of England. After lying on the seabed for 437 years, its hull was remarkably preserved due to a protective layer of silt and cold, low-oxygen waters. Its recovery in 1982 revealed a time capsule of Tudor life, including weapons, tools, and personal artifacts. This case underscores how specific environmental factors—such as sediment cover and low salinity—can halt the decay of wood, even over centuries.

In contrast, the Vasa, a Swedish warship that sank in 1628, spent 333 years underwater before its recovery in 1961. Unlike the Mary Rose, the Vasa was preserved in the brackish waters of Stockholm’s harbor, where low salt levels and cold temperatures inhibited shipworm activity, a primary destroyer of wooden wrecks. Its near-complete state allowed for meticulous restoration, making it a cornerstone of maritime archaeology. These examples highlight the critical role of water chemistry and temperature in determining a shipwreck’s longevity.

Another notable instance is the Antikythera Shipwreck, discovered off Greece in 1900, which dates back to around 70–60 BCE. Despite its age, wooden remnants were found alongside the famous Antikythera Mechanism, an ancient analog computer. The wreck’s preservation in the deep, cold waters of the Mediterranean demonstrates how depth can shield wooden structures from destructive surface conditions. However, much of its wooden hull had already deteriorated, emphasizing the limits of even the most favorable environments over millennia.

For those seeking to locate or study long-lasting wooden shipwrecks, focus on areas with cold, low-oxygen waters, such as the Baltic Sea or deep oceanic trenches. Avoid shallow, warm, or tropical waters, where shipworms and bacteria thrive. Additionally, shipwrecks buried in sediment or protected by artificial barriers, like underwater archaeological parks, are more likely to survive intact. By understanding these environmental factors, enthusiasts and researchers can better predict where wooden wrecks might endure and how to preserve them for future generations.

Wood Look Tile Lengths: Are Options Longer Than 48 Inches Available?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Wooden shipwrecks can survive underwater for hundreds or even thousands of years, depending on environmental conditions. Anaerobic (oxygen-depleted) environments, cold temperatures, and sediment burial can significantly slow decay.

The lifespan of wooden shipwrecks is influenced by factors like water salinity, temperature, oxygen levels, marine organisms, and human activity. Freshwater and cold environments generally preserve wood better than warm, salty seas.

Wooden shipwrecks typically decompose faster in saltwater due to higher levels of marine borers and microorganisms that feed on wood. Freshwater environments, especially those with low oxygen, can preserve wood for much longer.

Yes, recovered wooden shipwrecks can be preserved through conservation techniques like desalination, freeze-drying, and treatment with preservatives like polyethylene glycol (PEG) to prevent the wood from shrinking or cracking upon exposure to air.