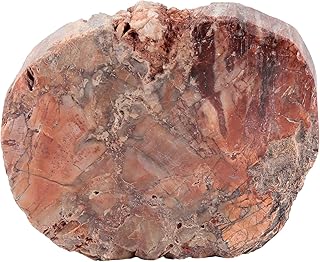

Petrified wood, a captivating natural wonder, is the result of a slow and intricate process that transforms ancient trees into stone over millions of years. This fascinating phenomenon begins when a tree is buried under sediment, such as volcanic ash, mud, or sand, cutting off oxygen and preventing decay. Over time, groundwater rich in minerals like silica, calcite, and pyrite seeps into the wood, gradually replacing the organic material cell by cell with these minerals. As the minerals crystallize, they preserve the original structure of the wood, including its rings and texture, creating a fossilized replica. The entire process, from burial to complete petrification, typically takes anywhere from 5,000 to 200,000 years, depending on environmental conditions and the availability of mineral-rich water. This remarkable transformation highlights the enduring interplay between time, geology, and biology.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Formation Time | Typically takes millions of years (25+ million years on average). |

| Process | Requires burial under sediment, mineral-rich water, and absence of oxygen. |

| Mineral Replacement | Quartz (silica) is the primary mineral replacing organic material. |

| Preservation | Original wood structure (cell walls, rings) is preserved in detail. |

| Environmental Conditions | Occurs in volcanic or sedimentary environments with high mineral content. |

| Common Locations | Found in areas like the Petrified Forest National Park (Arizona, USA). |

| Hardness | Petrified wood has a Mohs hardness of 7, similar to quartz. |

| Color Variation | Colors depend on minerals present (e.g., red from iron, yellow from manganese). |

| Fossil Type | Classified as a permineralized fossil. |

| Weight | Significantly heavier than original wood due to mineralization. |

Explore related products

$64.57 $77.99

What You'll Learn

- Conditions for Petrification: Requires buried wood, mineral-rich water, lack of oxygen, and millions of years

- Mineral Replacement Process: Silica, calcite, and pyrite gradually replace organic wood cell by cell

- Timeframe for Formation: Typically takes 5 to 50 million years to fully petrify

- Environmental Factors: Climate, sediment type, and water chemistry influence petrification speed

- Preservation of Details: Slow process preserves wood’s original structure, including rings and texture

Conditions for Petrification: Requires buried wood, mineral-rich water, lack of oxygen, and millions of years

Petrified wood doesn’t form in a forest or on a riverbank. It requires a burial, a slow submersion into sediment or volcanic ash that shields it from decay. This initial step is critical: exposure to air and moisture accelerates decomposition, but burial creates a protective cocoon. The wood must be quickly covered, often by mudslides, volcanic eruptions, or shifting riverbeds, to preserve its cellular structure before it disintegrates entirely. Without this burial, petrification cannot begin, no matter how mineral-rich the environment.

Once buried, the wood encounters its next essential ingredient: mineral-rich water. This water, often saturated with silica, calcium, or iron, seeps into the wood’s porous structure, replacing organic material cell by cell. The concentration of minerals matters—water with at least 100 parts per million of silica is ideal for silicification, the most common form of petrification. Over time, these minerals crystallize, hardening the wood into stone. Without this mineral-laden water, the wood might fossilize in other ways, but it won’t achieve the gemstone-like quality of true petrified wood.

Oxygen is the enemy of petrification. In its presence, bacteria and fungi thrive, breaking down the wood’s cellulose and lignin. To halt this decay, the buried wood must be in an oxygen-depleted environment, such as deep sediment or underwater. This anaerobic condition slows decomposition, giving minerals time to infiltrate and transform the wood. Even trace amounts of oxygen can disrupt the process, making the lack of it a non-negotiable requirement for petrification.

Finally, patience is paramount. Petrification is not a quick process; it demands millions of years. The transformation occurs at a glacial pace, with minerals gradually replacing organic matter. For example, the famous petrified forests in Arizona took over 200 million years to form, with silica from volcanic ash slowly turning ancient trees into quartz-rich stone. Rushing this process is impossible—it’s a testament to time’s relentless work. Without this vast timescale, the wood remains wood, not a fossilized marvel.

How Long Does a Cord of Wood Last Before Decay?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Mineral Replacement Process: Silica, calcite, and pyrite gradually replace organic wood cell by cell

The mineral replacement process is a meticulous, cell-by-cell transformation where silica, calcite, and pyrite infiltrate organic wood, preserving its structure while replacing its organic matter. This process, known as permineralization, is the cornerstone of petrified wood formation. Unlike fossilization methods that compress or mold organic material, permineralization creates a stone replica so detailed that even the wood’s original cellular patterns remain visible under magnification.

Imagine a tree trunk submerged in sediment-rich water, its cells slowly invaded by mineral-laden groundwater. Silica, often derived from volcanic ash or quartz-rich solutions, is the primary infiltrator, binding to cellulose fibers and hardening into chalcedony or quartz. Calcite, a calcium carbonate mineral, may also seep in, adding layers of crystalline structure. Less commonly, pyrite (fool’s gold) can replace organic matter, lending a metallic sheen to the fossilized wood. Each mineral deposits at varying rates, influenced by temperature, pressure, and the chemical composition of the surrounding environment. For instance, silica replacement occurs more rapidly in acidic, high-silica environments, while calcite dominates in alkaline conditions.

The timeline for this process is astonishingly variable, spanning from tens of thousands to millions of years. In ideal conditions—such as the silica-rich waters of the Yellowstone Petrified Forest—permineralization can occur within 10,000 to 20,000 years. However, most petrified wood specimens, like those found in Arizona’s Petrified Forest National Park, took 25 to 50 million years to form. The key factor is the consistent presence of mineral-rich groundwater and stable environmental conditions. Rapid burial under sediment shields the wood from decay, while slow, steady mineral infiltration ensures cell-by-cell replacement without structural collapse.

Practical observation of this process can be seen in laboratory experiments accelerating permineralization. By immersing wood samples in silica-saturated solutions at elevated temperatures (around 150°C), researchers achieve partial petrification within weeks. While this doesn’t replicate the natural timescale, it demonstrates the chemical mechanisms at play. For collectors or enthusiasts, identifying partially petrified wood—where organic material remains in the core—can provide a glimpse into the intermediate stages of this process.

The mineral replacement process is a testament to nature’s patience and precision. Each piece of petrified wood is a geological archive, its mineral composition and cellular detail revealing the environmental conditions of its formation. Whether silica, calcite, or pyrite dominates, the result is a transformation that bridges the organic and inorganic worlds, turning ancient wood into a durable, crystalline testament to time.

Seasoning Ash Wood: Optimal Time for Durability and Workability

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Timeframe for Formation: Typically takes 5 to 50 million years to fully petrify

The process of petrification is a testament to nature's patience, transforming organic wood into stone over an astonishingly long period. This geological marvel, known as petrified wood, is not a quick craft of the Earth but a slow, meticulous replacement of organic material with minerals, grain by grain. The timeframe for this transformation is as vast as the landscapes where these ancient relics are found, typically spanning 5 to 50 million years. This range is not arbitrary but a reflection of the intricate interplay between environmental conditions, mineral availability, and the unique characteristics of each piece of wood.

Consider the journey of a tree that falls in a mineral-rich environment, such as an ancient riverbed or volcanic ash deposit. Over time, sediments bury the wood, shielding it from decay. Groundwater, often rich in dissolved minerals like silica, permeates the wood, slowly replacing the organic cells with quartz or other minerals. This process, called permineralization, is the cornerstone of petrification. The speed at which this occurs depends on factors like temperature, pressure, and the concentration of minerals in the water. For instance, higher silica concentrations can accelerate the process, but even under optimal conditions, millions of years are required to fully petrify a piece of wood.

To put this timeframe into perspective, imagine the dinosaurs roaming the Earth. Many of the petrified wood specimens we marvel at today began their transformation during the Mesozoic Era, the age of dinosaurs. By the time humans evolved, these wooden relics had already been stone for millions of years. This staggering timescale highlights the rarity and value of petrified wood, which is not just a geological curiosity but a window into Earth's ancient past.

For enthusiasts and collectors, understanding this timeframe is crucial. While smaller pieces or those with favorable conditions may petrify closer to the 5-million-year mark, larger logs or those in less ideal environments can take up to 50 million years. This variability underscores the importance of preservation efforts, as once destroyed, petrified wood cannot be replaced within a human timescale. Practical tips for appreciating these treasures include visiting national parks like Petrified Forest National Park in Arizona, where millions of years of history are preserved, and avoiding the purchase of illegally collected specimens, which threaten these finite resources.

In conclusion, the formation of petrified wood is a geological marathon, not a sprint. Its timeframe of 5 to 50 million years is a reminder of the Earth's slow, relentless processes that shape our world. By understanding this, we gain not only a deeper appreciation for these stone fossils but also a sense of responsibility to protect them for future generations.

Andersen Wood Windows Lifespan: Durability, Maintenance, and Longevity Explained

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$6.99

Environmental Factors: Climate, sediment type, and water chemistry influence petrification speed

Petrified wood formation is a geological process heavily influenced by environmental factors, each playing a unique role in determining the speed and quality of petrification. Climate, sediment type, and water chemistry are the key players in this natural alchemy, transforming organic wood into stone over millennia.

Climate's Role: A Delicate Balance of Heat and Moisture

Temperature and humidity are critical in petrification. In arid climates, such as deserts, the process often stalls due to insufficient water to transport mineral-rich solutions. Conversely, tropical environments with high humidity and warmth accelerate the process by promoting rapid mineral infiltration. For instance, petrified forests in regions like Arizona’s Painted Desert formed over millions of years under conditions of alternating wet and dry periods, which allowed for both decay prevention and mineral deposition. Optimal petrification occurs in temperate climates with seasonal rainfall, where water can percolate through sediments without causing erosion.

Sediment Type: The Foundation of Mineralization

The type of sediment surrounding the wood dictates the availability of minerals and the rate of petrification. Fine-grained sediments like silt and clay provide a slow but steady diffusion of minerals, resulting in highly detailed preservation of wood structures. Coarse sediments like sand allow faster water flow but may yield less detailed fossilization. Volcanic ash, rich in silica, is particularly effective; it hardens into minerals like quartz, creating vibrant, crystalline patterns. For example, petrified wood in Indonesia’s Riau Province formed in volcanic ash layers, showcasing intricate cellular details preserved in quartz.

Water Chemistry: The Mineral Delivery System

The chemical composition of groundwater is the lifeblood of petrification. Water rich in dissolved silica, calcium, and iron accelerates the process by depositing minerals into the wood’s cellular structure. Acidic water, while effective in breaking down organic matter, can dissolve minerals before they precipitate, slowing petrification. Alkaline water, on the other hand, promotes mineral stability. Practical tip: In laboratory settings, petrification can be simulated by submerging wood in a solution of 10% silica gel and 90% water, with visible mineralization occurring within weeks under controlled conditions.

Interplay of Factors: A Symphony of Transformation

The speed of petrification is not determined by a single factor but by the interplay of climate, sediment, and water chemistry. For instance, a warm, humid climate paired with silica-rich sediment and alkaline water can reduce petrification time from millions to hundreds of thousands of years. Conversely, cold, dry climates with coarse sediment and acidic water may halt the process entirely. Understanding these interactions allows geologists to predict where petrified wood is likely to form and how long it will take, offering insights into Earth’s ancient environments.

Practical Takeaway: Accelerating Petrification for Art and Science

For those interested in creating petrified wood for art or study, mimic natural conditions by burying wood in silica-rich sediment, maintaining a pH of 7.5–8.5 in the surrounding water, and keeping the environment warm (25–30°C). Regularly saturate the sediment with mineral-rich water to ensure continuous deposition. While natural petrification takes millennia, this method can produce visually similar results in 1–2 years, though structural integrity will differ. Always handle chemicals with care and monitor pH levels to avoid unintended reactions.

Bondo Wood Filler Durability: Longevity and Performance Explained

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Preservation of Details: Slow process preserves wood’s original structure, including rings and texture

The slow transformation of wood into stone, a process known as petrification, is a testament to nature's meticulous craftsmanship. Over millions of years, this process preserves the wood's original structure, including its rings and texture, in astonishing detail. This preservation is not just a scientific curiosity but a window into the past, offering insights into ancient ecosystems and climates.

The Science Behind the Preservation

Petrification begins when wood is buried under sediment, cutting off oxygen and slowing decay. Groundwater rich in minerals like silica, calcite, and pyrite seeps into the wood, gradually replacing its organic cells with mineral deposits. This process, called permineralization, occurs at a glacial pace—often taking 5 to 50 million years. The key to preserving details lies in the slow, uniform infiltration of minerals, which replicate the wood's cellular structure layer by layer. Faster processes would result in a loss of texture and detail, but the deliberate pace ensures that even the finest annual growth rings and grain patterns remain intact.

Comparing Petrified Wood to Other Preservation Methods

Unlike mummification or amber preservation, petrification transforms the original material entirely, turning organic matter into stone. While mummification retains the wood's organic composition, it often results in brittleness and loss of detail over time. Amber, though preserving organisms in remarkable clarity, encapsulates rather than transforms. Petrification, however, creates a durable fossil that can withstand millennia of exposure to the elements. This durability, combined with the preservation of intricate details, makes petrified wood a unique and invaluable resource for paleontologists and geologists.

Practical Tips for Observing Petrified Wood

To appreciate the preserved details of petrified wood, examine a polished cross-section under a magnifying glass. Look for the distinct rings, which represent annual growth cycles, and the texture of the grain, which mirrors the wood’s original structure. For a deeper analysis, compare samples from different geological periods to observe variations in preservation quality. Museums and national parks, such as Petrified Forest National Park in Arizona, offer excellent opportunities to study these fossils firsthand. When handling petrified wood, avoid harsh chemicals or abrasive cleaners, as they can damage the surface and obscure details.

The Takeaway: A Slow Process with Lasting Impact

The preservation of wood’s original structure through petrification is a marvel of natural engineering. It reminds us that time, when given enough of it, can create something both beautiful and scientifically significant. By understanding the slow, deliberate process behind petrification, we gain not only a deeper appreciation for these ancient relics but also a clearer picture of Earth’s history. Whether you’re a scientist, a collector, or simply a curious observer, petrified wood offers a tangible connection to the past—one that has endured, detail by detail, for millions of years.

COVID-19 Survival on Wooden Toys: Duration and Safety Tips

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Petrified wood formation usually takes millions of years, often between 5 to 50 million years, depending on environmental conditions.

The time required depends on factors like the presence of silica-rich water, temperature, pressure, and the type of wood. Faster petrification occurs in environments with abundant minerals and stable conditions.

While rare, some accelerated petrification processes, such as those in volcanic or hydrothermal environments, can occur in as little as tens of thousands of years.

Petrification involves the slow replacement of organic material with minerals, a process that requires the gradual infiltration of mineral-rich water and the dissolution of wood cells, which is inherently time-consuming.

Scientists have experimented with artificial petrification using mineral solutions and controlled environments, but these methods still take years or decades, far shorter than natural processes but not instantaneous.