The transformation of wood into driftwood is a fascinating natural process influenced by various environmental factors. It typically begins when wood, often from fallen trees or branches, is carried by rivers or ocean currents, exposing it to saltwater, sunlight, and constant abrasion. The duration of this transformation can vary significantly, ranging from several months to several years, depending on the type of wood, its density, and the intensity of the environmental conditions it encounters. Softwoods, like pine, may break down more quickly, while hardwoods, such as oak, can take much longer to achieve the weathered, smoothed appearance characteristic of driftwood. Additionally, factors like temperature, wave action, and microbial activity play crucial roles in accelerating or slowing the process. Understanding this timeline not only sheds light on the natural recycling of organic materials but also highlights the unique beauty and value of driftwood in art, decor, and coastal ecosystems.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Time to Become Driftwood | 1-5 years (varies based on wood type, environmental conditions, and water exposure) |

| Wood Type Influence | Softwoods (e.g., pine) degrade faster (1-2 years); hardwoods (e.g., oak) take longer (3-5+ years) |

| Environmental Factors | Saltwater accelerates weathering; freshwater slows the process |

| Sun Exposure | UV rays speed up bleaching and drying |

| Wave Action | Constant movement smooths and shapes wood faster |

| Microbial Activity | Fungi and bacteria contribute to decomposition, especially in submerged wood |

| Temperature | Warmer climates expedite decomposition and weathering |

| Humidity | High humidity can prolong the process by preventing rapid drying |

| Final Driftwood Appearance | Smooth, bleached, weathered surface with rounded edges and potential marine organism attachments |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Natural Weathering Process

Wood transforms into driftwood through a natural weathering process that can take anywhere from several months to several decades, depending on environmental conditions and the type of wood. This process begins when wood is exposed to water, sunlight, and mechanical forces, which work together to break down its cellular structure. The initial stage involves waterlogging, where the wood absorbs moisture, causing it to swell and weaken. Over time, this moisture facilitates the growth of fungi and bacteria, which decompose lignin and cellulose, the primary components of wood. This biological degradation is a critical step in the transformation, as it softens the wood and makes it more susceptible to further weathering.

Mechanical forces, such as waves, tides, and sand abrasion, play a significant role in shaping driftwood. Constant movement in water acts like a natural sandpaper, smoothing edges and creating the distinctive worn appearance associated with driftwood. For example, wood in a fast-moving river may become driftwood in as little as 6 to 12 months due to the intense mechanical action, while wood in a calm lake might take 5 to 10 years to achieve the same level of weathering. The density and hardness of the wood also matter; softer woods like pine weather faster than denser woods like oak or teak.

Sunlight accelerates the weathering process by causing photodegradation, where ultraviolet (UV) rays break down surface fibers and fade the wood’s color. This is particularly evident in coastal environments, where wood is exposed to both saltwater and intense sunlight. Saltwater itself is corrosive, speeding up the breakdown of wood fibers and contributing to a more rapid transformation. In such conditions, wood can exhibit signs of driftwood characteristics within 1 to 3 years, though full transformation may still take longer.

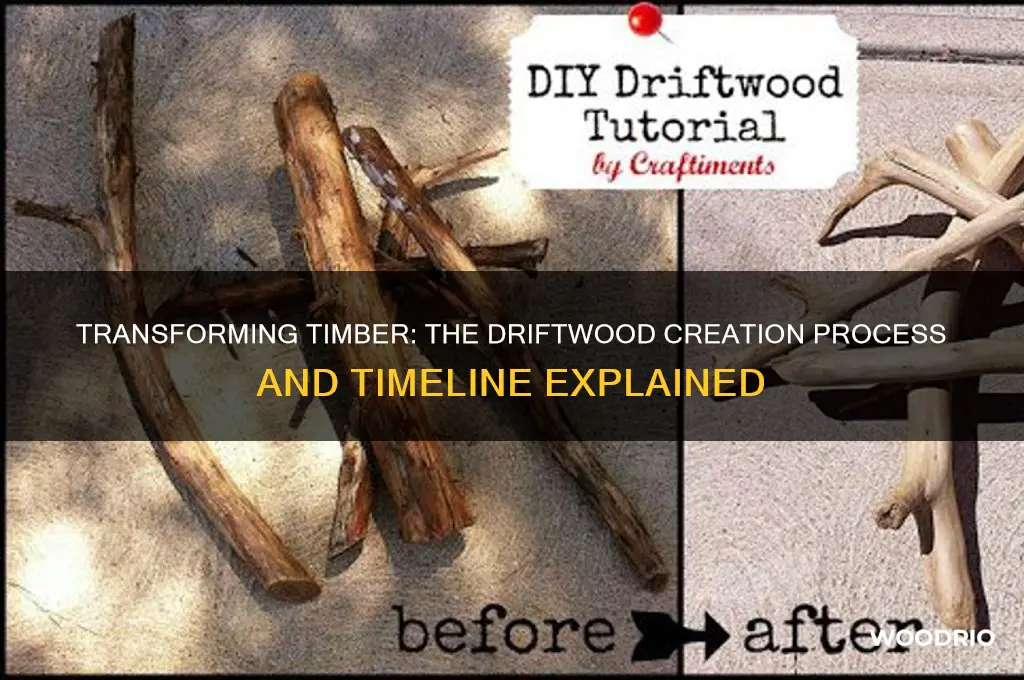

To replicate this process artificially, enthusiasts often submerge wood in saltwater or bury it in sand for 3 to 6 months, followed by exposure to sunlight. However, this method lacks the complexity of natural weathering, which includes unpredictable elements like storms, temperature fluctuations, and varying water chemistry. For those seeking authentic driftwood, patience is key, as nature’s process cannot be rushed without sacrificing the unique textures and patterns that define true driftwood.

Understanding the natural weathering process highlights why driftwood is both rare and valuable. It’s a testament to the interplay of biology, physics, and chemistry, shaping wood into a material prized for its beauty and character. Whether found on a beach or crafted by hand, driftwood tells a story of time, endurance, and transformation.

Mr. Garrison's Woodland Life: Duration and Survival Story Explored

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$17.97 $18.99

Water Exposure Duration

The transformation of wood into driftwood is a process heavily influenced by the duration of its exposure to water. While the exact timeline varies, understanding the key factors at play can provide a clearer picture. Generally, wood needs to be submerged or in constant contact with water for at least several months to begin the driftwood process. However, this is just the starting point; the full transformation can take years, depending on the type of wood, water conditions, and environmental factors.

From an analytical perspective, the rate of wood degradation is directly proportional to the duration and intensity of water exposure. Softwoods like pine or cedar, with their looser cell structures, can show signs of driftwood characteristics—such as bleaching and softening—within 6 to 12 months of continuous water contact. Hardwoods, like oak or teak, are more resistant and may require 2 to 5 years or more to exhibit similar traits. The water’s salinity, temperature, and movement also play critical roles; saltwater accelerates the process due to its corrosive properties, while warmer temperatures speed up microbial activity that breaks down the wood.

For those looking to create driftwood artificially, controlling water exposure duration is key. A practical method involves submerging wood in a saltwater solution for 3 to 6 months, regularly checking for desired changes. To expedite the process, increase the salt concentration (1 cup of salt per gallon of water) and maintain the wood in a warm, sunlit area. However, caution is necessary: prolonged exposure beyond 12 months can lead to excessive brittleness, rendering the wood unusable for certain projects.

Comparatively, natural driftwood undergoes a much longer and less controlled process. Wood in rivers or oceans may spend 5 to 10 years or more in the water, subjected to tides, currents, and varying climates. This extended exposure not only alters the wood’s appearance but also its structural integrity, making it lighter and more porous. The takeaway here is that while artificial methods can mimic driftwood in months, natural driftwood is the result of years of relentless water interaction, creating a unique texture and patina that’s hard to replicate.

Instructively, monitoring water exposure duration is essential for both natural and artificial driftwood creation. For natural enthusiasts, collecting wood from shorelines after at least 2 years of water exposure ensures it has begun the driftwood transformation. For DIY projects, start with shorter durations (3–6 months) and gradually extend the time based on the wood’s response. Always inspect the wood for mold or excessive decay, as these can compromise its quality. By balancing exposure time with environmental conditions, you can achieve the desired driftwood aesthetic while preserving the wood’s usability.

Night in the Woods DLC: Unveiling the Length of Its Nights

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Wood Type Influence

The transformation of wood into driftwood is a process heavily influenced by the type of wood involved. Hardwoods like oak or teak, known for their dense structure, resist decay and take significantly longer to break down—often requiring several years to a decade. In contrast, softwoods such as pine or cedar, with their looser grain and higher resin content, degrade more quickly, typically becoming driftwood within months to a few years. This disparity highlights how wood density and natural oils play a critical role in determining the timeline of driftwood formation.

Consider the practical implications for collectors or artisans. If you’re seeking driftwood for a project, softwoods like pine are ideal for quicker results, especially if you’re manually accelerating the process through techniques like soaking or sanding. However, for a more durable, weathered aesthetic, hardwoods like maple or walnut are worth the wait, as their slower transformation preserves intricate textures and shapes. Always factor in the wood’s origin—saltwater exposure accelerates breakdown, while freshwater environments prolong the process due to lower salinity.

From an environmental perspective, the wood type also dictates its ecological impact during transformation. Softwoods, which decompose faster, release nutrients into aquatic ecosystems more rapidly, benefiting local flora and fauna. Hardwoods, on the other hand, provide longer-lasting habitats for marine life as they slowly break down. For conservationists or hobbyists, understanding this distinction allows for informed decisions about sourcing and using driftwood responsibly, ensuring minimal disruption to natural habitats.

Finally, a comparative analysis reveals that while softwoods offer speed and accessibility, hardwoods deliver longevity and aesthetic richness. For instance, a piece of oak driftwood may take 5–10 years to achieve its distinctive silver-gray patina, whereas cedar might reach a similar state in just 1–2 years. Whether you prioritize time efficiency or the unique character of the wood, selecting the right type ensures your driftwood meets both functional and artistic needs. Always remember to check local regulations regarding driftwood collection to avoid legal or environmental pitfalls.

Polyurethane Application Guide: Ideal Timing Between Coats on Pine Wood

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Environmental Factors Role

The transformation of wood into driftwood is a process heavily influenced by environmental factors, each playing a unique role in determining the duration and outcome. Sun exposure, for instance, accelerates the breakdown of lignin, a key component in wood, causing it to become brittle and more susceptible to erosion. In tropical regions, where sunlight is intense, this process can occur within 6 to 12 months, whereas in temperate zones, it may take 2 to 3 years. The angle and duration of sunlight exposure also matter; wood on south-facing shores in the Northern Hemisphere, for example, degrades faster due to prolonged sun exposure.

Water salinity is another critical factor. Saltwater, with its higher mineral content, acts as a natural preservative in the early stages, slowing initial decay but later contributing to faster erosion once the wood’s structure weakens. Freshwater environments, on the other hand, promote faster fungal and bacterial growth, leading to quicker internal decay but slower surface erosion. A study in the Baltic Sea found that pine logs in brackish water (salinity 5–8 ppt) became driftwood in 3–5 years, while those in freshwater lakes took only 1–2 years due to microbial activity.

Wave action and tidal patterns dictate the physical wear on wood. Constant, moderate wave action in sheltered bays smooths wood surfaces over 1–2 years, creating the classic driftwood appearance. In contrast, violent waves in open ocean environments can shatter wood within months, leaving only smaller fragments. Tidal zones also play a role; wood exposed to alternating wet and dry conditions in intertidal areas experiences faster degradation due to osmotic stress, reducing transformation time by up to 50% compared to submerged wood.

Temperature fluctuations act as a catalyst, particularly in regions with distinct seasons. Freeze-thaw cycles in colder climates cause internal cracking, expediting decay. For example, wood in the Arctic Circle undergoes this process annually, becoming driftwood in 4–6 years, while wood in consistently warm equatorial waters may take 8–10 years due to the absence of such stress. Similarly, water temperature affects microbial activity; bacteria and fungi thrive in temperatures between 20–30°C, doubling decay rates in these conditions.

Finally, the presence of marine organisms can significantly alter the timeline. Shipworms, a type of wood-boring mollusk, can reduce a log to driftwood in as little as 6 months in infested waters. Barnacles and algae, while not directly destructive, add weight and alter buoyancy, increasing exposure to abrasive forces. To mitigate this, submerging wood in freshwater for 2 weeks before ocean exposure can deter initial colonization, prolonging the transformation process by up to a year. Understanding these factors allows for better prediction and manipulation of driftwood creation, whether for ecological studies or artistic purposes.

Dremel Wood Blade Lifespan: Factors Affecting Durability and Longevity

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Human-Accelerated Techniques

The natural process of transforming wood into driftwood can take decades, even centuries, as it relies on the slow dance of water, sun, and sand. But what if we could condense this timeline? Human-accelerated techniques offer a shortcut, harnessing tools and methods to mimic nature’s effects in a fraction of the time. By understanding these processes, enthusiasts and artisans can create driftwood-like pieces in weeks or months, rather than waiting for the ocean to do the work.

One effective method is the chemical weathering approach, which replicates the bleaching and softening effects of saltwater. Start by soaking the wood in a solution of 1 part hydrogen peroxide (3%) and 3 parts water for 24–48 hours. This breaks down lignin, the compound that gives wood its rigidity, and lightens its color. Follow this with a soak in a mixture of white vinegar and steel wool, which further ages the wood by creating a weathered, grayed appearance. Caution: Always wear gloves and work in a ventilated area when handling chemicals.

For a more hands-on technique, consider mechanical abrasion. Use a wire brush, sandpaper, or a power sander to physically distress the wood’s surface, mimicking the wear caused by sand and waves. Focus on edges and natural grain lines to create a realistic, weathered look. Combine this with a heat treatment—a propane torch or heat gun can char the wood slightly, adding depth and texture. Be mindful of temperature; too much heat can compromise the wood’s integrity.

A comparative analysis reveals that biological methods are another viable option. Submerging wood in a saltwater aquarium or burying it in beach sand introduces microorganisms that accelerate decay. While this method takes longer (2–6 months), it yields a more authentic texture. For faster results, pair this with periodic exposure to sunlight, which speeds up bleaching. This hybrid approach balances patience with proactive intervention, ideal for those seeking a natural yet expedited outcome.

In conclusion, human-accelerated techniques democratize the creation of driftwood, making it accessible to hobbyists and professionals alike. Whether through chemical, mechanical, or biological means, these methods offer control over time and outcome. Experimentation is key—combine techniques to achieve the desired effect, and always prioritize safety when using tools or chemicals. With these strategies, the transformation from raw wood to driftwood is no longer a waiting game but a craft to be mastered.

Cedar vs Pressure Treated Wood: Which Fence Lasts Longer?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The transformation of wood into driftwood typically takes several months to several years, depending on factors like the type of wood, water conditions, and exposure to sunlight and saltwater.

Yes, harder woods like oak or teak take longer to break down, while softer woods like pine or cedar become driftwood more quickly due to their lower density and faster degradation.

No, saltwater is more effective in breaking down wood due to its higher mineral content and the abrasive action of sand and waves, which accelerate the weathering process.

Yes, sunlight contributes to the bleaching and drying of wood, which are key steps in the driftwood formation process. However, prolonged exposure can also weaken the wood structure.

Yes, techniques like soaking wood in saltwater, sanding, or using chemical treatments can mimic natural weathering, significantly reducing the time it takes for wood to resemble driftwood.