Wood fossilization, a process known as permineralization, is a slow and intricate transformation that typically takes millions of years. It begins when wood is buried under sediment, shielding it from decay and oxygen, and allowing minerals from groundwater to gradually infiltrate its cellular structure. Over time, these minerals replace the organic material, preserving the wood’s original texture and structure in stone. The exact duration varies depending on factors such as the environment, mineral availability, and the depth of burial, but the process generally spans from several thousand to tens of millions of years, resulting in fossils like petrified wood that offer a glimpse into Earth’s ancient past.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Time for Wood Fossilization | Typically takes millions of years (10 million years or more) |

| Key Conditions | Anaerobic (oxygen-free) environment, rapid burial, high pressure |

| Initial Stage | Mineralization begins within 1,000 to 10,000 years |

| Complete Fossilization | Requires 10 million to 300 million years for full transformation |

| Preservation Factors | Lack of oxygen, acidic or alkaline groundwater, and sediment cover |

| Types of Wood Fossils | Petrified wood, coalified wood, mummified wood |

| Common Locations | Volcanic ash deposits, riverbeds, and swampy environments |

| Scientific Significance | Provides insights into ancient ecosystems and climate conditions |

| Notable Examples | Petrified Forest National Park (Arizona), USA (225 million years old) |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Factors Affecting Fossilization Time

Wood fossilization is a process influenced by a myriad of factors, each playing a pivotal role in determining the duration required for transformation. The journey from organic wood to fossilized remains is not a swift one; it spans millennia, with the earliest stages of preservation setting the pace for the entire process. The initial conditions under which the wood is buried are critical, as they dictate the subsequent chemical and physical changes that will occur over time.

The Role of Environment and Sedimentation

Fossilization thrives in environments where wood is rapidly buried under sediment, shielding it from oxygen and decomposing organisms. Anaerobic conditions, such as those found in deep lake beds, swamps, or volcanic ash deposits, slow decay and promote mineralization. For instance, wood buried in fine-grained sediments like silt or clay fossilizes faster than in coarse sand, as these materials provide better protection and facilitate mineral infiltration. Practical tip: Areas with high sediment accumulation rates, such as river deltas or volcanic regions, are prime locations for wood fossilization.

Chemical Composition and Wood Type

Not all wood is created equal in the fossilization race. Hardwoods, with their higher lignin content, resist decay longer than softwoods, giving them a head start in the preservation process. Lignin, a complex polymer, acts as a natural barrier to decomposition, but it must eventually be replaced by minerals like silica or calcite for fossilization to complete. Conifers, for example, fossilize more slowly due to their lower lignin density compared to angiosperms. Analytical insight: Wood with denser cell walls and higher resin content can take up to 10,000 years longer to fully fossilize than less resilient types.

Temperature and Pressure: The Geological Accelerators

Heat and pressure are silent catalysts in the fossilization timeline. Elevated temperatures, often found in deep sedimentary layers, accelerate chemical reactions, speeding up the replacement of organic material with minerals. Similarly, high pressure from overlying sediments compacts the wood, reducing pore space and limiting microbial activity. In geothermal areas, wood can fossilize in as little as 1,000 years, compared to the tens of thousands of years required in cooler, less pressurized environments. Caution: Extreme heat can also degrade wood before fossilization begins, so a balance is crucial.

Water Chemistry and Mineral Availability

The mineral composition of surrounding water is a decisive factor. Groundwater rich in silica, calcium, or iron provides the building blocks for permineralization, the process where minerals fill cellular spaces. Acidic water, however, can dissolve wood before fossilization occurs, while alkaline conditions promote preservation. For example, wood buried in iron-rich environments may fossilize into pyrite-infused specimens, a process that takes roughly 5,000 years. Comparative note: Fossilization in silica-rich waters, like those found near volcanic activity, typically completes in 2,000–3,000 years, whereas calcite-dominated environments may require up to 10,000 years.

Biological Interference and Preservation Techniques

Microorganisms and insects can either hinder or aid fossilization. Fungi and bacteria accelerate decay, breaking down wood before minerals can infiltrate, while certain bacteria can actually promote mineralization by creating conditions favorable for silica deposition. Human intervention, such as controlled burial in mineral-rich slurries, can reduce fossilization time to decades, though this is not a natural process. Practical takeaway: To preserve wood for potential fossilization, bury it in a sediment-rich, anaerobic environment with a pH above 7, ensuring minimal exposure to decomposers.

Understanding these factors allows us to predict fossilization timelines more accurately, ranging from a few thousand to millions of years. Each variable interacts dynamically, making every fossil a unique record of its environment and history.

Yellowjackets' Survival Timeline: How Long Were the Girls Lost in the Woods?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Types of Wood and Preservation Rates

Wood fossilization is a process heavily influenced by the type of wood involved, with denser, resin-rich species like conifers often preserving better than softer woods like balsa. Conifers, such as pine and redwood, contain high levels of lignin and resins, which act as natural preservatives, slowing decay and increasing the likelihood of fossilization. For instance, petrified redwood forests in California showcase how these resilient woods can endure millions of years under the right conditions. In contrast, deciduous trees like oak or maple, while harder than balsa, lack the same resinous compounds, making them more susceptible to decomposition unless rapidly buried in sediment.

The preservation rate of wood is not solely determined by its species but also by environmental factors. Rapid burial in anaerobic environments, such as deep lake beds or volcanic ash, significantly enhances preservation by shielding wood from oxygen and microorganisms. For example, the 200-million-year-old fossilized wood found in the Chinle Formation of Arizona was preserved due to quick burial in floodplain sediments. Conversely, wood exposed to air and water decomposes within decades, rarely surviving more than a few centuries without intervention.

To maximize preservation, consider the following practical steps: bury wood in clay-rich sediments, which minimize oxygen penetration, or submerge it in bodies of water with high mineral content, such as peat bogs. For experimental purposes, treat wood with silica-rich solutions to mimic petrification, though this process takes years, not centuries. Avoid using softwoods like cedar for long-term preservation projects, as their low resin content makes them poor candidates for fossilization.

Comparatively, the fossilization of wood can be accelerated in laboratory settings using high-pressure, mineral-rich solutions, but this remains an artificial process. Natural fossilization, however, is a testament to the unique properties of certain woods. For instance, the 390-million-year-old *Archaeopteris* fossils, among the earliest known woody plants, survived due to their rapid burial in ancient swamps. This highlights how specific wood types and environments are critical to preservation rates, offering insights into both paleontology and modern conservation techniques.

Woodpeckers' Long Beaks: Do They Really Eat Wood?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Environmental Conditions for Fossilization

Wood fossilization is a rare and intricate process, heavily dependent on specific environmental conditions that preserve organic material over millennia. The transformation of wood into fossils typically requires a unique combination of factors, including rapid burial, low oxygen levels, and the presence of mineral-rich water. These conditions prevent the wood from decaying and allow minerals to gradually replace the organic structure, creating a fossilized replica. Without such environments, wood usually decomposes quickly, leaving no trace behind.

To foster fossilization, the wood must be buried swiftly, often by sediment from rivers, volcanic ash, or mudslides. This rapid burial shields the wood from oxygen and microorganisms that cause decay. For instance, fossilized forests found in areas like the Yellowstone Petrified Forest were preserved due to volcanic ash entombing the trees. The speed of burial is critical; slower processes allow decomposition to outpace preservation, rendering fossilization impossible.

Another crucial factor is the presence of mineral-rich groundwater, which permeates the buried wood and replaces its cellular structure with minerals like silica, calcite, or pyrite. This process, known as permineralization, is more likely in environments with high mineral content, such as river deltas or areas with volcanic activity. The pH and chemical composition of the water also play a role; neutral to slightly alkaline conditions are ideal, as acidic water can dissolve organic material before fossilization occurs.

Climate and geography further influence fossilization potential. Arid regions, for example, are less conducive to wood preservation because they lack the water necessary for mineral transport. Conversely, wetland or swamp environments, where waterlogged conditions slow decay, are prime locations for fossilization. The age of the wood at the time of burial matters too; younger, more resilient wood has a higher chance of surviving the early stages of fossilization than older, more brittle material.

Practical considerations for preserving wood in modern settings can draw from these natural processes. For instance, burying wood in sediment-rich, low-oxygen environments, such as the bottom of a pond or lake, mimics the conditions necessary for fossilization. Adding mineral-rich water or soil can accelerate permineralization, though this process still takes thousands of years. While artificial fossilization is not feasible on human timescales, understanding these conditions can inform conservation efforts for existing fossils and archaeological sites.

When Does Green Wood Crack? Understanding Splitting Timeframes

You may want to see also

Explore related products

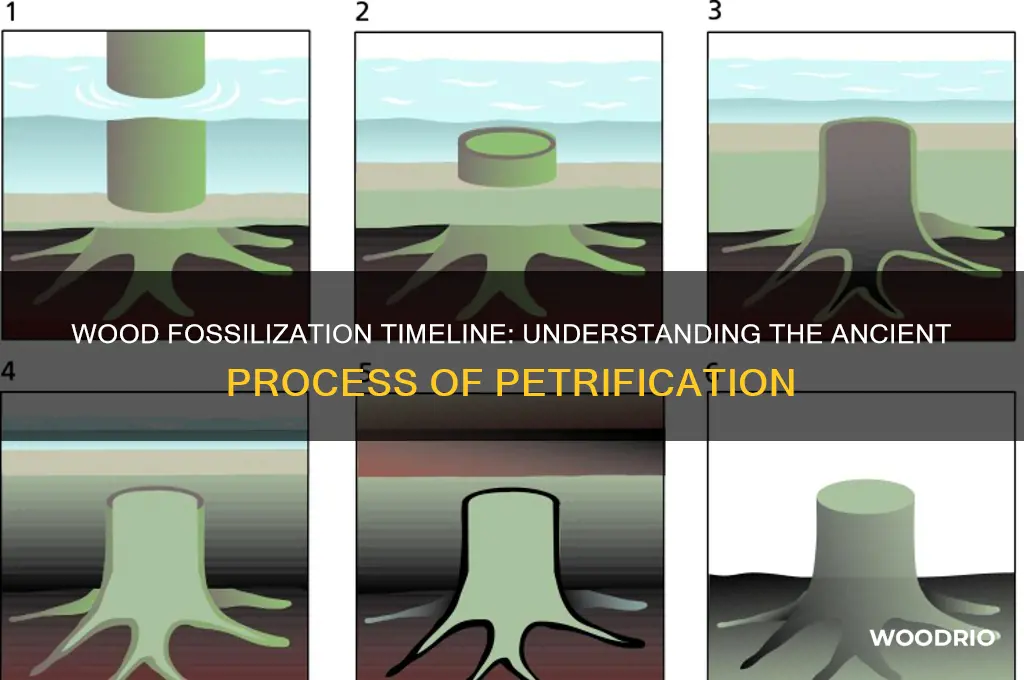

Stages of Wood Fossil Formation

Wood fossilization is a complex process that transforms organic material into stone over millennia, but it doesn’t happen by chance. The journey begins with rapid burial, a critical first stage that shields the wood from decay and scavengers. In environments like riverbeds, volcanic ash deposits, or peat bogs, wood is quickly covered by sediment, cutting off oxygen and slowing bacterial activity. For example, the famous petrified forests of Arizona owe their existence to ancient trees buried under volcanic ash and mud, preserving them from complete decomposition. Without this initial step, the wood would disintegrate, leaving nothing behind but fragments.

The next stage involves mineral infiltration, where groundwater rich in minerals like silica, calcite, or pyrite seeps into the buried wood’s cellular structure. Over time, these minerals replace the organic matter cell by cell, a process known as permineralization. This transformation is slow, often taking thousands to millions of years, depending on the mineral content of the surrounding sediment and the flow rate of groundwater. The result is a fossil that retains the wood’s original structure, including growth rings and even cellular details, but is now composed of stone. Interestingly, the color of the fossilized wood depends on the minerals present—iron oxides create reds and yellows, while manganese produces blacks and blues.

As the wood undergoes permineralization, it enters a stabilization phase, where the organic material is almost entirely replaced by minerals, leaving behind a rock-hard replica. This stage is crucial for long-term preservation, as the fossilized wood becomes resistant to erosion and weathering. However, not all wood reaches this point; some pieces may only partially fossilize, retaining a mix of organic and mineralized material. Full stabilization requires consistent environmental conditions, such as stable groundwater flow and mineral availability, which explains why some fossilized wood is more durable than others.

The final stage is exposure and discovery, where geological processes like erosion gradually uncover the fossilized wood. This can take millions of years, as layers of sediment above the fossil are worn away by wind, water, or ice. For instance, the petrified wood found in Argentina’s Patagonia region was exposed after glacial activity eroded the surrounding rock. Once revealed, these fossils provide invaluable insights into ancient ecosystems, climate conditions, and even evolutionary history. However, exposure also makes them vulnerable to weathering and human activity, underscoring the need for conservation efforts to protect these natural treasures.

Understanding these stages highlights the rarity and significance of wood fossils. From rapid burial to mineral infiltration, stabilization, and eventual exposure, each step requires specific conditions and immense time. While the process can take anywhere from 10,000 to several million years, the result is a testament to nature’s ability to preserve history in stone. For enthusiasts and researchers alike, recognizing these stages not only deepens appreciation for fossilized wood but also guides efforts to locate and protect these ancient relics.

Durability of Wooden Phone Cases: Lifespan and Longevity Explained

You may want to see also

Examples of Fossilized Wood Ages

Fossilized wood, also known as petrified wood, offers a tangible link to Earth’s ancient past, with some specimens dating back millions of years. One striking example is the Araucarioxylon arizonicum, found in the Petrified Forest National Park in Arizona. These fossilized logs are approximately 225 million years old, hailing from the Late Triassic period. Their preservation is so detailed that original tree ring patterns remain visible, providing insights into the climate and environment of the time. This example underscores the immense timescale required for wood to fossilize fully, often spanning epochs.

In contrast, younger examples of fossilized wood demonstrate that the process can occur over shorter periods under specific conditions. The Baltic amber, which often contains fossilized wood fragments, dates back to the Eocene epoch, roughly 44 million years ago. Here, the rapid burial of wood in resin allowed for preservation over a relatively "shorter" geological timescale. This highlights how environmental factors, such as the presence of resin or mineral-rich water, can accelerate fossilization, though still requiring millions of years.

For those seeking more recent examples, the La Brea Tar Pits in Los Angeles provide a unique case study. Fossilized wood found here, alongside ice age mammals, dates back approximately 40,000 to 11,000 years. While not fully petrified, these specimens are preserved through tar infiltration, showcasing a different mechanism of fossilization. This example illustrates that partial preservation can occur over tens of thousands of years, though complete petrification remains a far lengthier process.

Practical takeaways from these examples include the importance of burial conditions in determining fossilization timelines. Wood buried in sediment-rich environments with high mineral content, like those in Arizona, typically undergoes full petrification over millions of years. Conversely, wood encased in resin or tar may preserve organic structures more rapidly but remains a product of deep time. For enthusiasts or researchers, identifying the context of fossilized wood—whether in amber, tar, or sedimentary rock—can provide clues to its age and the processes that preserved it.

Wooden Fascias Lifespan: Factors Affecting Durability and Longevity

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Wood fossilization typically takes millions of years, often ranging from 10 million to several hundred million years, depending on environmental conditions.

Fossilization requires rapid burial in sediment, low oxygen levels to prevent decay, and the presence of minerals that can replace organic material over time.

No, wood fossilization is most likely in environments like swamps, riverbeds, or volcanic ash deposits where burial and mineral-rich water are present.

The process is called permineralization, where minerals gradually infiltrate the wood’s cellular structure, replacing organic matter with stone-like material.

No, fossilized woods vary depending on the minerals involved. For example, petrified wood is often quartz-based, while coal is a different type of fossilized plant material.