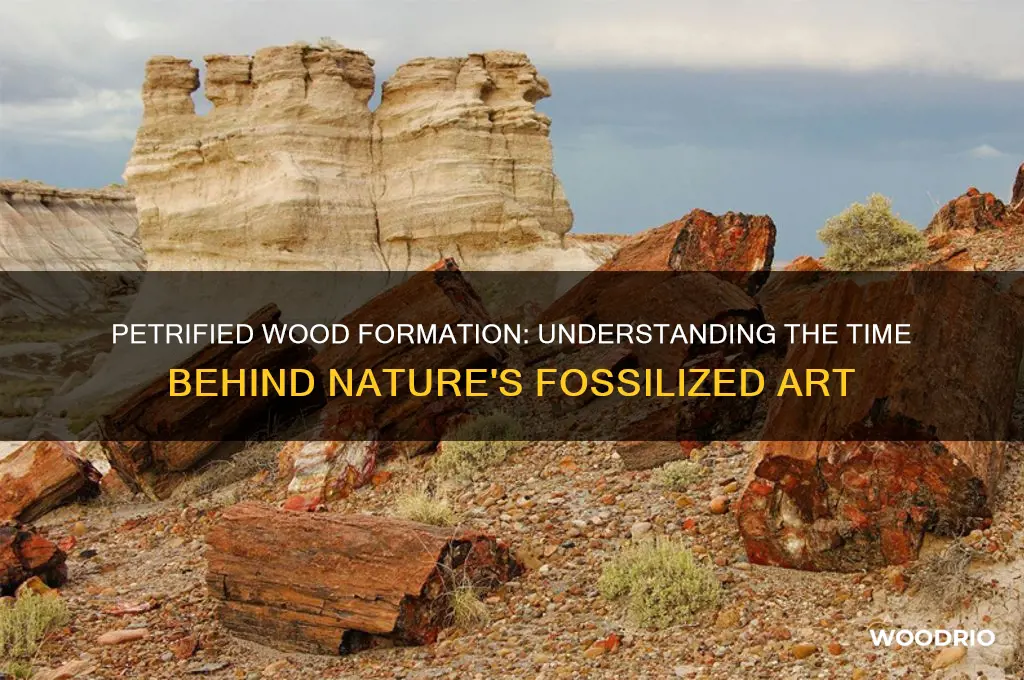

Petrified wood, a captivating natural wonder, is the result of a slow and intricate process that transforms ancient trees into stone over millions of years. This fascinating phenomenon begins when a tree is buried under sediment, such as volcanic ash, mud, or sand, cutting off oxygen and preventing decay. Over time, groundwater rich in minerals like silica seeps into the wood, gradually replacing the organic material with minerals cell by cell. The duration of this process varies widely, typically spanning 5 to 50 million years, depending on factors like mineral availability, temperature, and pressure. The end result is a stunning fossilized replica of the original wood, often retaining its original structure and detail, but now composed entirely of stone. Understanding the timeline of petrified wood formation offers a glimpse into Earth’s geological history and the patience of natural processes.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Time to Form Petrified Wood | Typically takes millions of years (25-200+ million years) |

| Key Process | Permineralization (replacement of organic material with minerals like silica) |

| Required Conditions | Burial under sediment, presence of groundwater rich in minerals, lack of oxygen |

| Minerals Involved | Quartz (most common), calcite, pyrite, opal, and others |

| Preservation of Original Structure | Cell-by-cell replacement preserves original wood structure and details |

| Factors Affecting Speed | Temperature, mineral concentration, pH, and pressure |

| Examples of Formation Speed | Some rare cases can form in thousands of years under ideal conditions |

| Common Locations | Fossil forests (e.g., Petrified Forest National Park, Arizona, USA) |

| Appearance | Colorful, crystalline patterns due to varying mineral deposits |

| Scientific Significance | Provides insights into ancient ecosystems, climate, and geological history |

Explore related products

$64.57 $77.99

What You'll Learn

- Formation Process Overview: Sediment fills wood, minerals replace organic matter, fossilization completes over millions of years

- Mineral Replacement Rate: Silica or calcite replaces wood cells slowly, typically at microscopic levels annually

- Environmental Factors: Water, sediment type, temperature, and pressure influence petrification speed and quality

- Timeframe Estimates: Petrification ranges from 1,000 to millions of years, depending on conditions

- Preservation Conditions: Anaerobic environments and rapid burial significantly speed up the petrification process

Formation Process Overview: Sediment fills wood, minerals replace organic matter, fossilization completes over millions of years

Petrified wood is not formed overnight; it’s a geological marathon spanning millions of years. The process begins when a tree dies and falls into an environment rich in sediment, such as a riverbed or volcanic ash deposit. Over time, this sediment buries the wood, shielding it from decay and creating the perfect conditions for preservation. This initial step is critical—without rapid burial, the wood would decompose, leaving nothing behind.

Once buried, groundwater seeps through the sediment, carrying dissolved minerals like silica, calcite, or pyrite. These minerals gradually infiltrate the wood’s cellular structure, replacing the organic matter cell by cell. This mineralization process, known as permineralization, transforms the wood into stone while often preserving intricate details like growth rings and even cellular patterns. The type of mineral present in the groundwater determines the final color and composition of the petrified wood, with silica typically producing quartz-rich specimens.

Fossilization is not a quick event; it requires immense patience from the Earth itself. The complete transformation from organic wood to petrified stone can take anywhere from 5 million to 200 million years, depending on environmental conditions. Factors like temperature, pressure, and mineral availability influence the speed of this process. For example, wood buried in volcanic ash, rich in silica, may petrify faster than wood submerged in a slow-moving river.

Practical tip: If you’re interested in witnessing this process firsthand, visit areas with abundant petrified wood, such as the Petrified Forest National Park in Arizona. Here, you can see examples of wood that began its transformation over 200 million years ago during the Late Triassic period. While you can’t speed up the process, understanding its stages allows you to appreciate the remarkable journey from tree to timeless fossil.

In summary, the formation of petrified wood is a testament to nature’s patience and precision. From sediment burial to mineral replacement, each step is a delicate balance of chemistry and geology. While the process is too slow to observe in a human lifetime, its results offer a tangible connection to Earth’s ancient past, reminding us of the enduring legacy of life and time.

How Long Does Wood Filler Take to Dry? A Quick Guide

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Mineral Replacement Rate: Silica or calcite replaces wood cells slowly, typically at microscopic levels annually

Petrified wood is a testament to nature’s patience, formed through a process called permineralization, where minerals like silica or calcite infiltrate and replace organic wood cells. This transformation occurs at a glacial pace, with mineral replacement happening at microscopic levels annually. To put it in perspective, a single cubic millimeter of wood might take decades to fully mineralize, depending on environmental conditions. This slow rate is why petrified wood often retains intricate details of the original wood structure, such as growth rings and cellular patterns, despite being millions of years old.

Understanding the mineral replacement rate is crucial for appreciating the timescale involved in petrification. Silica, the most common mineral in this process, dissolves from volcanic ash or sedimentary rocks and seeps into buried wood through groundwater. Each year, only a fraction of the wood’s cellular structure is replaced, with the thickness of mineral deposition measured in micrometers. For example, a 1-centimeter-thick layer of silica might take 10,000 years to form under ideal conditions. This incremental process explains why petrified wood is often found in areas with a history of volcanic activity or mineral-rich groundwater.

The rate of mineral replacement is not uniform; it depends on factors like temperature, pressure, and mineral availability. In warmer environments, chemical reactions accelerate, potentially increasing the annual replacement rate. Conversely, colder or drier conditions slow the process. For instance, wood buried in a hot spring might mineralize faster than wood in a desert. Practical tip: Geologists often study the mineral composition of petrified wood to estimate the paleoenvironment in which it formed, as different minerals indicate specific conditions.

Comparing silica and calcite replacement reveals distinct outcomes. Silica, being harder and more durable, preserves finer details and produces more vibrant colors due to impurities like iron or manganese. Calcite, softer and more soluble, tends to create a more uniform, chalky appearance. However, calcite replacement can occur faster in carbonate-rich environments, such as ancient seabeds. This comparison highlights how the choice of mineral influences both the rate and aesthetic of petrification, offering clues to the wood’s geological history.

For enthusiasts or collectors, understanding this slow process underscores the rarity and value of petrified wood. It’s not just a rock; it’s a fossilized record of ancient forests, preserved through millennia of microscopic mineralization. To protect these treasures, avoid exposing petrified wood to harsh chemicals or extreme temperatures, which can degrade its structure. Instead, display it in a stable environment to preserve its natural beauty. Takeaway: The mineral replacement rate is a reminder of nature’s meticulous craftsmanship, turning organic matter into geological art over millions of years.

Exploring Muir Woods: Time Needed for a Complete Tour

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Environmental Factors: Water, sediment type, temperature, and pressure influence petrification speed and quality

Water is the lifeblood of petrification, acting as both a transporter and a catalyst. Groundwater rich in dissolved minerals like silica, calcium, and iron is essential for the process. The speed of petrification is directly tied to the flow rate and mineral concentration of this water. Slow-moving, mineral-laden water allows for gradual and even infiltration of the wood’s cellular structure, resulting in finer, more detailed fossilization. Conversely, fast-flowing water may lead to uneven mineral deposition, creating less aesthetically pleasing or structurally sound petrified wood. For optimal results, environments with consistent, gentle water flow—such as ancient riverbeds or floodplains—are ideal.

Sediment type plays a pivotal role in determining the quality and speed of petrification. Fine-grained sediments like silt and clay provide a more uniform matrix for mineral deposition, often yielding highly detailed petrified wood. Coarser sediments, such as sand or gravel, allow for faster water flow but may result in larger, less intricate crystal formations. The pH and chemical composition of the sediment also matter; acidic sediments can dissolve wood more rapidly, while alkaline sediments promote mineral precipitation. For enthusiasts seeking to replicate petrification, using a mixture of fine clay and silica-rich sand in controlled experiments can mimic natural conditions and accelerate the process.

Temperature and pressure are silent architects of petrification, subtly shaping its timeline and outcome. Lower temperatures slow the chemical reactions involved in mineralization, extending the petrification process but often enhancing the clarity and detail of the fossilized wood. Higher temperatures accelerate reactions but may lead to coarser, less refined structures. Pressure, typically from overlying sediment or rock, aids in compacting the wood and forcing minerals into its pores. In deep sedimentary basins, where pressure is high and temperatures moderate, petrification can occur within thousands of years. For artificial petrification, maintaining a temperature range of 50–100°F (10–38°C) and applying gentle pressure through weighted layers of sediment can simulate these conditions.

The interplay of these environmental factors underscores the complexity of petrification. For instance, a log buried in a cool, clay-rich environment with slow groundwater flow might petrify over 5,000 years, while one in a warmer, sandy setting could fossilize in half that time but with less detail. Understanding these dynamics not only deepens appreciation for natural petrified wood but also empowers experimental efforts. By manipulating water flow, sediment composition, temperature, and pressure, enthusiasts can shorten the petrification timeline from millennia to decades, creating their own fossilized masterpieces.

Wood Putty Drying Time: Factors Affecting Cure and Finish

You may want to see also

Timeframe Estimates: Petrification ranges from 1,000 to millions of years, depending on conditions

Petrified wood doesn't form overnight—it’s a process measured in millennia, not minutes. The transformation of organic material into stone, known as petrification, hinges on a delicate interplay of environmental conditions. At its core, this process requires three key elements: burial, mineral-rich water, and time. While the minimum timeframe hovers around 1,000 years, the upper limit stretches into the millions, rivaling the lifespan of entire civilizations. This vast range underscores the variability in how nature crafts these geological wonders.

Consider the steps involved: first, a tree must fall and become buried under sediment, shielding it from decay. Next, groundwater rich in minerals like silica seeps into the wood, gradually replacing its organic cells with crystalline structures. The speed of this mineralization depends on factors like temperature, pressure, and the concentration of minerals in the water. In environments with ideal conditions—such as volcanic ash deposits or arid riverbeds—petrification can occur more rapidly. Conversely, less favorable settings may require millions of years to achieve the same result. For instance, the famous petrified forests in Arizona formed over 200 million years, a testament to the patience of geological processes.

To put this into perspective, imagine a tree felled during the time of the dinosaurs. Over epochs, its remains are slowly infiltrated by minerals, cell by cell, until it becomes a stone replica of its former self. This isn’t a quick fix—it’s a marathon, not a sprint. For those seeking to replicate petrification artificially, the process can be accelerated but still demands years. Laboratory experiments using high-pressure, mineral-saturated solutions have achieved partial petrification in decades, a mere fraction of the natural timeline. However, these methods lack the nuance and completeness of nature’s work.

Practical takeaways abound for enthusiasts and collectors. When identifying petrified wood, look for telltale signs like preserved grain patterns or vibrant mineral hues, which indicate a lengthy and thorough petrification process. Avoid pieces that appear porous or incomplete, as these may not have fully transformed. For those curious about the science, studying the mineral composition of petrified wood can reveal clues about the ancient environment in which it formed. Whether you’re a geologist, a hobbyist, or simply fascinated by Earth’s history, understanding the timeframe of petrification deepens appreciation for these fossilized treasures.

In essence, petrification is a masterclass in patience, blending chemistry, geology, and time into a single artifact. Its timeframe, spanning from thousands to millions of years, reflects the diversity of Earth’s processes and the uniqueness of each specimen. By grasping this range, we not only gain insight into the past but also learn to value the slow, relentless work of nature in shaping the world around us.

How Long Does a Half Cord of Wood Typically Last?

You may want to see also

Preservation Conditions: Anaerobic environments and rapid burial significantly speed up the petrification process

The transformation of wood into stone, a process known as petrification, is a geological marvel that typically spans millions of years. However, certain conditions can accelerate this process, making it a fascinating subject for both scientists and enthusiasts. Among these, anaerobic environments and rapid burial stand out as critical factors that significantly shorten the petrification timeline.

Anaerobic environments, devoid of oxygen, play a pivotal role in preserving organic materials. In such settings, the absence of oxygen inhibits the activity of microorganisms that would otherwise decompose the wood. This preservation is crucial because the initial stages of petrification require the wood's cellular structure to remain intact. For instance, in waterlogged anaerobic conditions, such as those found in deep lake sediments or swampy areas, wood can be preserved for thousands of years without significant decay. This extended preservation period allows more time for the mineralization process to begin and progress.

Rapid burial is another key factor that expedites petrification. When wood is quickly buried under layers of sediment, it is shielded from the elements and potential biological degradation. This burial creates a stable environment where minerals can gradually infiltrate the wood's cellular structure. The speed of burial is essential because it minimizes exposure to oxygen and other degrading agents. For example, volcanic ash or mudslide deposits can bury wood almost instantaneously, providing an ideal setting for petrification to commence rapidly. Studies have shown that wood buried under such conditions can begin to mineralize within a few thousand years, compared to the millions of years it might take under less optimal circumstances.

To illustrate the impact of these conditions, consider the famous petrified forests found in places like Arizona's Petrified Forest National Park. Here, ancient trees were rapidly buried by volcanic ash and mudflows, creating an anaerobic environment that preserved the wood. Over time, groundwater rich in minerals like silica seeped into the wood, replacing the organic material cell by cell with quartz and other minerals. This process, known as permineralization, was significantly accelerated by the initial preservation conditions, resulting in the stunningly detailed petrified wood we see today.

For those interested in the practical aspects of petrification, creating an anaerobic environment and ensuring rapid burial can be simulated in controlled settings. For instance, submerging wood in a sealed container filled with a mineral-rich solution and kept in a dark, oxygen-free environment can mimic natural conditions. While this process still takes years, it is considerably faster than waiting for natural geological processes. Additionally, burying wood in fine sediment layers, such as clay or silt, and keeping it in a stable, undisturbed location can further enhance the chances of successful petrification.

In conclusion, while petrification is inherently a slow process, anaerobic environments and rapid burial can dramatically reduce the time required. These conditions preserve the wood's structure and provide an ideal setting for mineralization to occur. Whether in nature or simulated environments, understanding and manipulating these factors can offer valuable insights into the fascinating process of turning wood into stone.

Durability of Wooden Decks: Lifespan, Maintenance, and Longevity Tips

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Petrified wood formation typically takes millions of years, often ranging from 5 to 20 million years, depending on environmental conditions.

The process involves tree burial, mineral-rich water infiltration, and gradual replacement of organic material with minerals like silica, quartz, or calcite over millions of years.

While rare, petrification can occur more quickly (tens of thousands of years) in environments with high mineral concentrations and ideal pressure/temperature conditions, but it still requires significant time.

The slow process is due to the gradual replacement of organic matter with minerals, which occurs at a microscopic level and depends on the availability of minerals and stable environmental conditions.

Yes, scientists can accelerate petrification in lab settings using high-pressure and mineral-rich solutions, but even then, the process takes years, not centuries or millennia.