The transformation of wood into coal is a fascinating geological process known as coalification, which occurs over millions of years under specific conditions. It begins with the burial of plant material, such as wood, in oxygen-poor environments like swamps or peat bogs, where decomposition is slowed. Over time, layers of sediment accumulate, subjecting the organic matter to increasing heat and pressure. This gradual process drives off moisture and volatile compounds, leaving behind carbon-rich material. The duration of this transformation varies depending on factors like temperature, pressure, and the depth of burial, but it typically takes anywhere from 10 million to 300 million years for wood to fully convert into coal. This natural process highlights the immense timescales involved in Earth’s geological and biological cycles.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Process Name | Coalification |

| Time Required | Millions of years (typically 1-300 million years, depending on conditions) |

| Key Factors Influencing Speed | Temperature, pressure, depth of burial, oxygen availability, type of wood |

| Stages of Coal Formation | Peat → Lignite → Sub-bituminous coal → Bituminous coal → Anthracite |

| Optimal Conditions | Anaerobic (oxygen-free) environment, high pressure, and elevated temperatures |

| Initial Stage (Peat Formation) | Takes thousands of years under waterlogged conditions |

| Transformation to Anthracite | Requires the longest time (up to 300 million years) |

| Role of Heat and Pressure | Increases carbon content and energy density, reducing moisture and volatile matter |

| Geological Setting | Occurs in sedimentary basins with thick layers of organic material |

| Human Timescale Comparison | Far beyond human lifespans or historical records |

| Modern Simulation (Artificial Coal) | Can be accelerated to days or weeks in lab settings, but not natural coal |

Explore related products

$34.01 $44.95

What You'll Learn

- Factors Affecting Coalification: Pressure, temperature, time, and burial depth influence wood-to-coal transformation

- Stages of Coal Formation: Peat, lignite, bituminous, and anthracite are sequential coal stages

- Timeframe for Coalification: Millions of years are required for wood to fully transform into coal

- Role of Anaerobic Conditions: Oxygen absence is crucial for preserving organic material during coal formation

- Geological Processes Involved: Sedimentation, compaction, and heat drive the wood-to-coal conversion process

Factors Affecting Coalification: Pressure, temperature, time, and burial depth influence wood-to-coal transformation

The transformation of wood into coal, a process known as coalification, is not a simple or quick event. It requires a precise combination of environmental conditions that work in tandem over millions of years. Among the critical factors influencing this metamorphosis are pressure, temperature, time, and burial depth. Each of these elements plays a unique role, and their interplay determines the efficiency and outcome of the coalification process.

Pressure and Its Role in Coalification

Pressure acts as a compressive force, squeezing out moisture and volatile compounds from the buried wood. As organic material is buried deeper beneath sedimentary layers, the overlying weight increases, subjecting it to higher pressures. For instance, pressures of 1,000 to 15,000 pounds per square inch (psi) are typical in coal-forming environments. This compression not only reduces the volume of the material but also enhances the density of the carbon structure, a key characteristic of coal. Without sufficient pressure, the transformation stalls, leaving the wood in an intermediate state like peat.

Temperature: The Catalyst for Chemical Change

Temperature is the driving force behind the chemical reactions that convert wood into coal. As burial depth increases, the Earth’s geothermal gradient exposes the organic material to higher temperatures, typically ranging from 50°C to 200°C (122°F to 392°F). At these temperatures, complex polymers in the wood break down, releasing hydrogen and oxygen while concentrating carbon. This process, known as carbonization, is essential for coal formation. However, extreme temperatures can lead to the formation of graphite rather than coal, highlighting the need for a balanced thermal environment.

Time: The Unhurried Architect of Coal

Coalification is a testament to patience, requiring millions of years to complete. The minimum timeframe for wood to transform into lignite (brown coal) is approximately 1 million years, while higher-grade coals like bituminous or anthracite can take up to 350 million years. This extended duration allows for the gradual removal of impurities and the stabilization of the carbon structure. Accelerating this process artificially is nearly impossible, as it relies on natural geological conditions that unfold over epochs.

Burial Depth: The Gateway to Coalification

Burial depth is the initial trigger for coalification, determining the extent to which pressure and temperature can act on the organic material. Wood must be buried at depths of at least 10 meters (33 feet) to initiate the process, though most coal seams form at depths exceeding 1,000 meters (3,280 feet). At these depths, the absence of oxygen prevents decay, preserving the organic matter for further transformation. Shallow burial often results in peat, while deeper burial fosters the development of higher-grade coals.

Practical Takeaways for Understanding Coalification

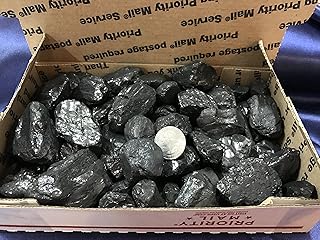

To appreciate the complexity of coalification, consider the following: a single lump of coal represents the compressed remains of ancient forests, subjected to immense pressure, heat, and time. For those studying geology or energy resources, understanding these factors provides insights into coal quality and distribution. For environmentalists, it underscores the non-renewable nature of coal, formed over timescales far beyond human lifespans. By examining these factors, we gain a deeper respect for the geological processes that shape our planet’s resources.

Petrified Oak: Understanding the Timeframe for Wood Fossilization

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$10.92 $18.98

Stages of Coal Formation: Peat, lignite, bituminous, and anthracite are sequential coal stages

The transformation of wood into coal is a geological process spanning millions of years, driven by heat, pressure, and time. This journey begins with peat, a spongy, soil-like material formed from partially decayed plant matter in waterlogged environments like swamps. Over millennia, as layers of sediment accumulate and compress peat, it evolves through distinct stages: lignite, bituminous coal, and finally anthracite. Each stage reflects increasing carbon content, energy density, and maturity, shaped by the intensity of heat and pressure applied during burial.

Peat: The First Step

Peat marks the earliest stage of coal formation, typically accumulating in peat bogs where acidic, oxygen-poor conditions slow decomposition. It contains roughly 60% carbon and retains much of its original plant structure, making it a low-energy fuel. Peat formation takes approximately 10,000 years under optimal conditions, though this can vary based on climate and vegetation. Harvested sustainably, peat is used in horticulture, but its extraction often raises environmental concerns due to habitat disruption.

Lignite: The Brown Coal

As peat is buried deeper beneath sedimentary layers, increased heat and pressure transform it into lignite, often called brown coal. This stage takes an additional 1–3 million years, depending on geological conditions. Lignite contains 60–70% carbon, with higher energy content than peat but still significant moisture and volatile matter. Its soft, crumbly texture and low heating value make it less efficient than later coal stages, though it remains a significant energy source in regions like Germany and Australia.

Bituminous Coal: The Workhorse

Further burial and heat exposure convert lignite into bituminous coal, a harder, denser material with 70–85% carbon content. This stage requires another 5–10 million years, as temperatures rise to 100–200°C (212–392°F). Bituminous coal is the most abundant and widely used type, prized for its versatility in electricity generation, steel production, and industrial processes. Its higher energy density and lower moisture make it more efficient than lignite, though it still releases significant emissions when burned.

Anthracite: The Black Diamond

The final stage, anthracite, is the highest grade of coal, formed under extreme pressure and temperatures exceeding 200°C (392°F) over 20–30 million years. With 86–98% carbon, anthracite is hard, glossy, and nearly pure, burning cleaner and hotter than other coals. Its rarity—less than 1% of global coal reserves—and high energy output make it valuable for heating and metallurgical applications. Anthracite’s formation requires specific geological conditions, limiting its availability to regions like Pennsylvania’s Coal Region.

Practical Takeaway

Understanding these stages highlights the immense time and energy invested in coal formation, underscoring its non-renewable nature. While coal remains a critical energy source, its extraction and combustion contribute to environmental challenges. Transitioning to sustainable alternatives is essential, but in the interim, prioritizing higher-grade coals like anthracite can reduce emissions. For those in coal-dependent industries, investing in carbon capture technologies or renewable energy sources offers a pathway to balance energy needs with environmental stewardship.

How Long Does 2 Bundles of Firewood Typically Last?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Timeframe for Coalification: Millions of years are required for wood to fully transform into coal

The transformation of wood into coal, a process known as coalification, is a geological journey spanning millions of years. It begins with the burial of plant material in oxygen-poor environments, such as swamps or peat bogs, where decomposition is slowed. Over time, layers of sediment accumulate, compressing the organic matter and driving off volatile compounds like water and gases. This gradual process, influenced by heat and pressure from the Earth’s crust, eventually converts the plant material into peat, then lignite, and finally into bituminous or anthracite coal. Each stage requires specific conditions and immense time, underscoring the patience of geological processes.

To put this timeframe into perspective, consider that the coal we extract today often dates back to the Carboniferous period, approximately 300 to 360 million years ago. During this era, vast forests dominated the Earth, and their remains were preserved under ideal conditions for coalification. Modern wood, if subjected to the same conditions, would follow a similar path, but it would take millions of years to achieve the same result. This highlights the non-renewable nature of coal and the stark contrast between human timescales and geological ones.

From a practical standpoint, understanding the coalification process is crucial for industries reliant on coal. For instance, the quality of coal—whether it’s lignite, bituminous, or anthracite—depends on the duration and intensity of heat and pressure it has experienced. Lignite, formed after a few million years, has lower energy content, while anthracite, requiring over 300 million years, is more energy-dense. Engineers and geologists use this knowledge to assess coal reserves and predict their suitability for specific applications, such as power generation or steel production.

A comparative analysis reveals that coalification is not just a linear process but a spectrum influenced by environmental factors. For example, wood buried in deeper, hotter sedimentary basins will transform more rapidly than that in shallower regions. Similarly, the type of plant material—whether it’s woody trees or soft vegetation—affects the final coal composition. This variability emphasizes the complexity of natural processes and the need for precise geological modeling to estimate coal formation rates.

In conclusion, the coalification of wood is a testament to the Earth’s ability to transform organic matter into valuable resources over unimaginable timescales. While the process is slow and irreversible on human timescales, its study offers insights into Earth’s history, energy resources, and the delicate balance of geological forces. For those in energy or environmental fields, appreciating this timeframe is essential for sustainable resource management and informed decision-making.

How Quickly Does Mold Grow on Wood Surfaces?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Role of Anaerobic Conditions: Oxygen absence is crucial for preserving organic material during coal formation

The absence of oxygen, or anaerobic conditions, is a silent guardian in the ancient process of coal formation, ensuring the preservation of organic material over millions of years. When wood and plant matter are buried under layers of sediment, the lack of oxygen prevents the complete decomposition that would otherwise occur in aerobic environments. This preservation is the first step in the long journey from wood to coal, setting the stage for the subsequent transformations driven by heat and pressure. Without anaerobic conditions, the organic material would break down entirely, leaving nothing behind to form the carbon-rich deposits we recognize as coal.

Consider the practical implications of this process. In environments where oxygen is present, microorganisms thrive, breaking down organic matter into simpler compounds like carbon dioxide and water. However, in oxygen-deprived settings, such as deep swamp sediments or buried forests, this microbial activity is halted. For instance, peat bogs, which are often the precursors to coal, are characterized by waterlogged, anaerobic conditions that slow decay. Over time, as layers of sediment accumulate, the organic material is compressed, and the absence of oxygen ensures that the carbon within the plant matter remains intact, rather than being released into the atmosphere.

Anaerobic conditions also play a critical role in the chemical changes that occur during coalification. As the buried organic material is subjected to increasing heat and pressure, the absence of oxygen prevents oxidation reactions that could destroy the carbon framework. Instead, volatile compounds like hydrogen and oxygen are expelled, leaving behind a more carbon-rich residue. This process, known as carbonization, is a direct result of the anaerobic environment, which shields the organic material from destructive chemical interactions. Without this protective barrier, the transformation of wood into coal would be significantly hindered, if not impossible.

To illustrate the importance of anaerobic conditions, compare the fate of wood in aerobic versus anaerobic environments. In a forest, fallen trees decompose rapidly due to oxygen-dependent microorganisms, returning their carbon to the ecosystem within years. In contrast, wood buried in an anaerobic swamp can persist for millennia, eventually becoming part of a coal seam. This stark difference highlights the pivotal role of oxygen absence in preserving organic material for the extended periods required for coal formation. Practical applications of this principle can be seen in modern biomass preservation techniques, where anaerobic conditions are artificially created to slow decay and retain organic integrity.

In conclusion, the role of anaerobic conditions in coal formation is both fundamental and transformative. By preventing decomposition and oxidation, oxygen absence ensures that organic material is preserved long enough to undergo the necessary geological processes. This natural mechanism not only explains how wood turns into coal over millions of years but also offers insights into preserving organic matter in contemporary contexts. Understanding and replicating these conditions can have far-reaching implications, from energy resource management to environmental conservation.

Heart Wood Pellets Lifespan: Durability, Storage Tips, and Longevity Explained

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Geological Processes Involved: Sedimentation, compaction, and heat drive the wood-to-coal conversion process

The transformation of wood into coal is a geological journey spanning millions of years, driven by three primary processes: sedimentation, compaction, and heat. It begins with the burial of wood in environments like swamps or bogs, where oxygen is limited, preventing complete decay. Over time, layers of sediment accumulate, burying the wood deeper and deeper, a process known as sedimentation. This step is crucial, as it shields the organic material from erosion and exposure to air, setting the stage for the next phases of coalification.

Compaction follows as the weight of overlying sediment presses down on the buried wood, squeezing out moisture and volatile compounds. This mechanical process, combined with mild heat from the Earth’s interior, initiates the breakdown of complex organic molecules. The wood’s structure becomes denser, gradually losing its original cellular composition. For instance, lignite, the earliest form of coal, retains enough plant structure to be recognizable, but further compaction and heat transform it into bituminous coal, a harder, more energy-dense material.

Heat plays a pivotal role in the final stages of coalification, acting as a catalyst for chemical changes. As buried wood is subjected to temperatures between 50°C and 200°C, depending on depth and geothermal gradients, it undergoes pyrolysis—a thermal decomposition process that breaks down organic matter into simpler hydrocarbons. This stage is critical for the formation of anthracite, the highest grade of coal, which contains up to 95% carbon. The duration of this process varies, but it typically requires 10 to 300 million years, depending on the specific conditions of heat and pressure.

Understanding these geological processes highlights the immense timescale and specific conditions required for coal formation. Sedimentation provides the protective environment, compaction initiates structural changes, and heat drives the chemical transformation. Together, these processes illustrate why coal is a non-renewable resource—its creation far outpaces human timescales. For practical purposes, this knowledge underscores the importance of conserving existing coal reserves and transitioning to sustainable energy sources, as the natural replenishment of coal is virtually impossible within a human timeframe.

In summary, the wood-to-coal conversion is a testament to Earth’s geological patience, involving sedimentation to bury, compaction to densify, and heat to transform. Each step is indispensable, and their interplay over millions of years results in the fossil fuel we extract today. This process not only explains coal’s formation but also emphasizes its finite nature, urging a reevaluation of our energy consumption habits.

Carbon vs. Wood Hockey Sticks: Which Material Offers Longer Durability?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The natural process of wood turning into coal, known as coalification, typically takes millions of years. It requires specific conditions, such as high pressure, heat, and the absence of oxygen, usually found in sedimentary basins.

Yes, wood can be transformed into a coal-like substance called "biocoal" or "torrefied wood" through artificial processes like torrefaction. This method takes only a few hours to a day, but the resulting product is not identical to natural coal.

Wood needs to be buried under layers of sediment, subjected to high pressure and temperatures (typically 50–200°C), and isolated from oxygen. Over time, these conditions break down the organic material, removing volatile compounds and leaving behind carbon-rich coal.

No, not all buried wood becomes coal. The process requires specific geological conditions and a long time frame. Most buried organic matter decomposes completely or turns into other substances like oil or natural gas, depending on the environment.

![On the Conditions of the Deposition of Coal More Especially as Illustrated by the Coal-Formation of Nova Scotia and New Brunswick / by J.W. Dawson 1866 [Leather Bound]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/617DLHXyzlL._AC_UY218_.jpg)

![Sunlight® Charcoal Tablets for Incense – Quick Light Coal Tablets – Charcoal Disks – 40 mm Coal Rolls – Coal Briquettes – Slow Burn - Instant Lighting [100]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/81jL961OxxL._AC_UL320_.jpg)