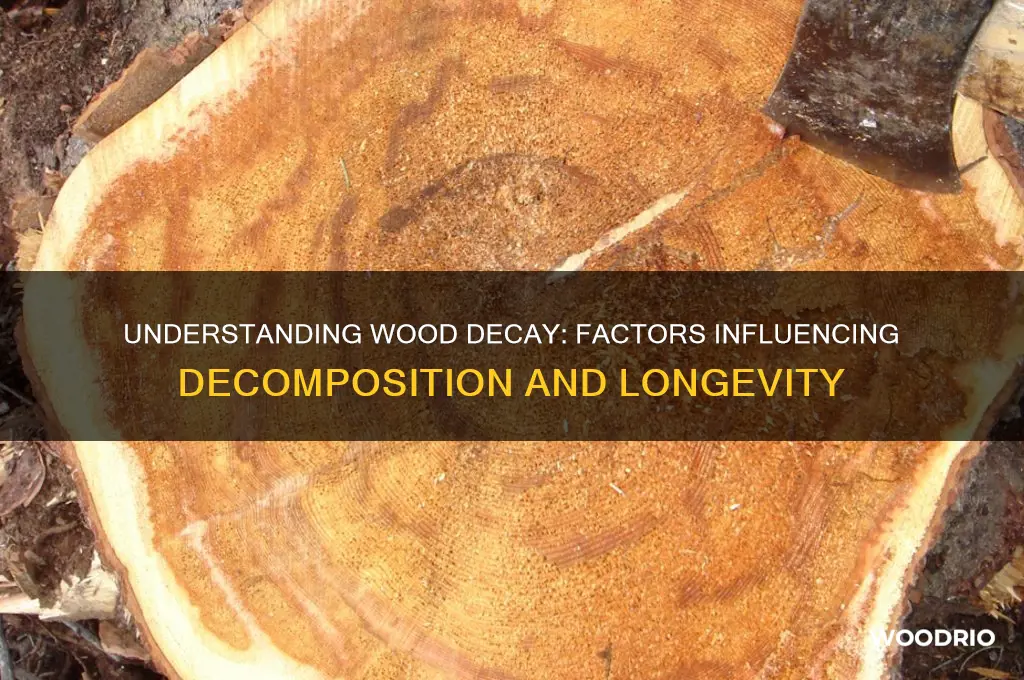

Wood decay is a natural process influenced by various factors, including moisture, temperature, and the presence of fungi or insects. The duration of wood decay can vary significantly, ranging from a few years to several decades, depending on the type of wood, environmental conditions, and exposure to decay-causing agents. Hardwoods like oak and teak generally resist decay longer than softwoods such as pine, while constant moisture and warm temperatures accelerate the process. Understanding these factors is crucial for predicting wood longevity and implementing effective preservation methods.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Factors accelerating decay: moisture, fungi, insects, temperature, wood type

- Decay timeline: softwoods vs. hardwoods, environmental conditions impact

- Preventing decay: treatments, storage, ventilation, regular maintenance

- Signs of decay: discoloration, softness, cracks, fungal growth

- Decay in structures: foundations, framing, outdoor wood longevity

Factors accelerating decay: moisture, fungi, insects, temperature, wood type

Wood decay is a natural process, but certain factors can significantly accelerate it, turning decades of durability into mere years. Among these, moisture stands out as the primary culprit. Wood is hygroscopic, meaning it absorbs and retains water, which creates an ideal environment for decay. When wood’s moisture content exceeds 20%, fungi and bacteria thrive, breaking down cellulose and lignin, the structural components of wood. Prolonged exposure to rain, humidity, or standing water can reduce a wooden structure’s lifespan from 50 years to less than 10. To mitigate this, ensure wood is properly sealed, elevated above ground, and regularly inspected for water damage.

Fungi are the silent architects of wood decay, responsible for over 90% of cases. They secrete enzymes that digest wood fibers, turning sturdy beams into brittle, crumbly remnants. Common culprits include brown rot, white rot, and soft rot fungi, each targeting specific wood components. For instance, brown rot fungi degrade cellulose, leaving behind a dry, cracked surface. Preventing fungal growth requires reducing moisture and applying fungicides. A study by the Forest Products Laboratory found that wood treated with copper-based preservatives can resist fungal decay for up to 40 years, compared to untreated wood, which may succumb in as little as 5 years in damp conditions.

Insects, though small, can deliver a devastating blow to wood’s integrity. Termites, carpenter ants, and powderpost beetles bore into wood, creating tunnels that weaken its structure. A single termite colony can consume up to 16 grams of wood per day, compromising a wooden beam in as little as 3–5 years. Regular inspections and treatments, such as borate-based insecticides, are essential. For example, pressure-treated wood with insecticides can deter termites for over 20 years, while untreated wood may fall victim within a decade in high-risk areas.

Temperature plays a dual role in wood decay, influencing both moisture levels and biological activity. In warm, humid climates, decay accelerates as fungi and insects thrive. For instance, wood in tropical regions may decay in 5–10 years without protection, compared to 20–30 years in cooler, drier areas. Conversely, extreme cold can slow decay but may cause wood to crack, creating entry points for moisture and pests. To combat temperature-related decay, choose wood species suited to your climate and apply protective coatings. Cedar and redwood, for example, are naturally resistant to decay and can last 20–30 years outdoors without treatment.

Not all wood is created equal when it comes to decay resistance. Hardwoods like teak and oak contain natural oils and tannins that deter fungi and insects, often lasting 30–50 years outdoors. Softwoods, such as pine, decay more rapidly unless treated, typically lasting 5–15 years. Pressure-treated wood, infused with preservatives, can extend lifespan to 40 years or more. When selecting wood, consider its intended use and environmental exposure. For ground contact, opt for treated wood with a retention level of 0.40 pounds per cubic foot (pcf) of preservative, which provides maximum protection against decay and insects.

Wood Pellets vs. Propane: Comparing Fuel Longevity for Grilling

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Decay timeline: softwoods vs. hardwoods, environmental conditions impact

Wood decay is a race against time, and the starting line depends largely on whether you're dealing with softwoods or hardwoods. Softwoods, like pine and spruce, are more susceptible to decay due to their lower density and higher resin content, which can actually attract certain fungi. Under ideal conditions for decay—moisture, warmth, and oxygen—softwoods can begin to show signs of deterioration within 5 to 10 years. Hardwoods, such as oak and teak, are denser and often contain natural compounds that resist fungal growth, typically lasting 25 to 50 years or more before significant decay sets in. This disparity highlights the importance of material selection in applications where longevity is critical.

Environmental conditions act as accelerants or inhibitors in the decay process, dramatically altering the timeline for both softwoods and hardwoods. High humidity and frequent rainfall create a breeding ground for fungi and bacteria, speeding up decay. For instance, wood in direct contact with soil can decay in as little as 2 to 5 years, while wood in dry, well-ventilated environments may last decades. Temperature also plays a role: warmer climates accelerate decay by fostering microbial activity, whereas colder regions may slow it down. Practical tip: elevate wooden structures off the ground and apply water-repellent treatments to mitigate moisture exposure.

The interplay between wood type and environmental factors reveals fascinating nuances. Softwoods in arid regions, like pine used in desert landscaping, can outlast hardwoods in tropical climates, where constant moisture undermines even the densest woods. For example, cedar, a softwood naturally resistant to decay, can survive 30+ years in dry conditions but may succumb in 10 years in a damp, shaded area. Conversely, hardwoods like ipe, known for their durability, can last 40+ years in tropical environments but may still fail prematurely if water pools on their surface. This underscores the need to match wood type to its environment and implement protective measures.

To maximize wood lifespan, consider these actionable steps: first, choose the right wood for the job—opt for naturally rot-resistant species like redwood or cypress in wet areas. Second, treat wood with preservatives; borate-based solutions penetrate deeply and are effective against fungi and insects. Third, design structures to minimize water retention—sloped surfaces and proper drainage are key. Finally, monitor wood regularly for early signs of decay, such as discoloration, softness, or fungal growth, and address issues promptly. By understanding the decay timeline and environmental impact, you can strategically extend the life of wooden materials in any setting.

Elmer's Glue on Wood: Durability and Adhesion Time Explained

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Preventing decay: treatments, storage, ventilation, regular maintenance

Wood decay is a relentless process, but it’s not inevitable. By understanding the factors that accelerate deterioration—moisture, fungi, and insects—you can implement targeted strategies to preserve wood for decades, even centuries. Treatments, storage, ventilation, and regular maintenance form the cornerstone of effective decay prevention, each playing a unique role in safeguarding wood’s structural integrity and aesthetic appeal.

Treatments act as the first line of defense, chemically or physically altering wood to resist decay. Pressure-treating wood with preservatives like chromated copper arsenate (CCA) or alkaline copper quaternary (ACQ) penetrates the material, inhibiting fungal growth and insect infestation. For interior wood, borate-based solutions are effective, but they must be reapplied every 5–10 years, depending on exposure to moisture. Natural oils like linseed or tung oil provide a barrier against moisture while allowing the wood to breathe, ideal for furniture or decorative pieces. Always follow manufacturer guidelines for application rates—typically 1–2 coats for oils and precise pressure settings for chemical treatments.

Storage and ventilation are equally critical, particularly for wood in humid or outdoor environments. Store wood in dry, elevated spaces to prevent ground moisture absorption, using pallets or racks to allow airflow beneath. For long-term storage, maintain humidity levels below 19% to discourage fungal growth. In construction, design structures with ventilation in mind: incorporate gaps in decking, use breathable membranes in timber framing, and ensure proper drainage to prevent water pooling. A well-ventilated attic, for instance, can extend the lifespan of wooden beams by reducing condensation and mold risk.

Regular maintenance transforms prevention from theory to practice, catching vulnerabilities before they escalate. Inspect wood annually for cracks, splinters, or discoloration, addressing issues promptly with sealants or repairs. Reapply water-repellent finishes every 2–3 years, especially in high-exposure areas like decks or siding. For older wood, consider professional assessments to detect hidden decay using tools like moisture meters or sonic tomography. Even small actions, like trimming vegetation away from wooden structures to reduce moisture retention, can significantly prolong wood’s life.

By integrating treatments, thoughtful storage, strategic ventilation, and consistent maintenance, you create a holistic defense against decay. While no method guarantees immortality for wood, these measures can extend its lifespan from a few years to several generations. The key lies in proactive, informed care—treating wood not as a static material but as a living resource that demands respect and attention.

Stardew Valley Hardwood Respawn Time: How Long to Wait?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Signs of decay: discoloration, softness, cracks, fungal growth

Wood decay is a silent process, often unnoticed until it’s too late. One of the earliest signs is discoloration, which manifests as dark streaks, patches, or a general dulling of the wood’s natural hue. This occurs because fungi, the primary culprits of decay, release enzymes that break down lignin, a key component of wood’s structure. For instance, brown rot fungi cause a brownish discoloration, while white rot fungi leave behind a lighter, bleached appearance. If you notice these changes, especially in areas prone to moisture, it’s a red flag that decay has begun.

Softness is another telltale sign, easily detected by pressing a screwdriver or thumb into the wood’s surface. Healthy wood resists pressure, but decayed wood feels spongy or crumbles under minimal force. This occurs as cellulose, the wood’s primary structural material, is broken down by fungi. A simple test: if your thumb penetrates the wood’s surface, it’s likely compromised. This is particularly concerning in load-bearing structures, where softness can lead to structural failure. Regularly inspect wooden beams, posts, and flooring, especially in damp environments like basements or crawl spaces.

Cracks often accompany decay, forming as the wood loses its structural integrity. These aren’t typical age-related cracks but rather deep, irregular fissures that expose the wood’s inner layers. Fungi weaken the wood’s fibers, causing it to shrink and split. In advanced cases, you may notice the wood peeling or flaking, resembling the layers of an onion. If you spot such cracks, particularly in combination with discoloration or softness, it’s time to assess the extent of the damage and consider replacement.

Fungal growth is the most visible and alarming sign of decay. It appears as fuzzy, thread-like structures (mycelium) or mushroom-like fruiting bodies on the wood’s surface. These growths indicate that fungi are actively feeding on the wood, accelerating its deterioration. For example, bracket fungi, often seen as shelf-like structures on tree trunks or wooden structures, are a clear sign of advanced decay. If you observe fungal growth, act promptly: remove the affected wood and address the moisture source to prevent further spread.

In summary, recognizing the signs of decay—discoloration, softness, cracks, and fungal growth—is crucial for preserving wooden structures. Early detection can save time, money, and safety hazards. Regular inspections, especially in moisture-prone areas, are key. If you notice any of these signs, take immediate steps to mitigate the damage, such as improving ventilation, applying fungicides, or replacing the affected wood. Ignoring these warnings can lead to irreversible structural damage, turning a minor issue into a major problem.

Maximizing Wood Mizer Blade Lifespan: Durability and Maintenance Tips

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Decay in structures: foundations, framing, outdoor wood longevity

Wood decay in structures is a silent threat that can compromise the integrity of foundations, framing, and outdoor elements if left unchecked. Moisture, fungi, and insects are the primary culprits, accelerating deterioration in environments where wood remains damp or lacks proper ventilation. For instance, foundation wood in direct contact with soil can decay within 5–10 years, while framing in well-ventilated interiors may last 50+ years. Understanding these vulnerabilities is the first step in mitigating decay and extending the lifespan of wooden components.

Foundations bear the brunt of decay due to their proximity to moisture-rich soil. Pressure-treated wood, infused with preservatives like chromated copper arsenate (CCA), can resist decay for 40 years or more in foundation applications. However, untreated wood in the same location rarely lasts beyond a decade. To combat this, ensure proper drainage systems are installed, use moisture barriers like gravel or plastic sheeting, and opt for treated lumber rated for ground contact. Regular inspections for signs of rot or insect damage are equally critical, as early detection can prevent costly repairs.

Framing decay often stems from hidden moisture intrusion, such as leaks or poor insulation. In humid climates, untreated framing in attics or crawl spaces may show signs of fungal growth within 15–20 years. To safeguard framing, maintain consistent indoor humidity below 50% using dehumidifiers, seal gaps around windows and doors, and promptly repair roof leaks. Borate-based wood treatments, applied during construction, can also inhibit fungal and insect activity, adding decades to the framing’s lifespan.

Outdoor wood structures, like decks and fences, face relentless exposure to weather extremes. Cedar and redwood, naturally resistant to decay, can endure 20–30 years without treatment, while pine typically lasts 5–10 years. To maximize longevity, apply a water-repellent sealer annually and re-stain every 2–3 years. Elevating structures on concrete piers or using composite materials can further reduce ground moisture exposure. For existing decay, replace affected boards promptly and ensure proper spacing for airflow to prevent future issues.

Comparing decay rates highlights the importance of material selection and maintenance. While untreated wood in foundations may fail in a decade, pressure-treated alternatives quadruple its lifespan. Similarly, proactive measures like sealing and ventilation can double the life of framing and outdoor structures. By investing in preventive strategies and choosing the right materials, homeowners can significantly delay decay, ensuring structural integrity and reducing long-term costs.

Understanding Morning Wood Duration: How Long Does It Typically Last?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Wood decay can begin within weeks to months after exposure to moisture, fungi, and insects, depending on environmental conditions.

Moisture, temperature, type of wood, presence of fungi or insects, and exposure to soil or water significantly affect decay speed.

Complete decay can take anywhere from a few years to several decades, depending on the factors mentioned above.

Treated wood can still decay, but it typically lasts 10–30 years or more, depending on the treatment type and environmental exposure.

![Preservation [Import]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/81+IBpvrysL._AC_UL320_.jpg)

![Preservation Society [DVD]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/31AJS2ZS1YL._AC_UL320_.jpg)

![Permanent Preservation Edition 500 Series the Eternal [Blu-ray]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/71qvs2rUzfL._AC_UL320_.jpg)