The process of wood petrification, also known as fossilization, is a fascinating natural phenomenon that transforms organic wood into stone-like material over an incredibly long period. This transformation occurs when wood becomes buried under sediment, cutting off oxygen and slowing decay, while minerals from groundwater gradually infiltrate the cellular structure, replacing organic matter with minerals like silica, calcite, or pyrite. The time required for wood to fully petrify varies widely, typically ranging from thousands to millions of years, depending on factors such as the mineral content of the surrounding environment, temperature, pressure, and the type of wood. While smaller pieces may petrify in a few thousand years, larger logs or entire trees can take significantly longer, often requiring millions of years to complete the process. Understanding this timeline highlights the remarkable interplay between geology, chemistry, and biology in preserving ancient organic materials.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition of Petrification | Process where organic wood is replaced by minerals, turning it to stone |

| Timeframe for Petrification | Typically millions of years (e.g., 5–50 million years) |

| Key Factors Affecting Speed | Burial depth, mineral-rich environment, lack of oxygen, pressure |

| Minerals Involved | Silica (most common), calcite, pyrite, other minerals |

| Preservation Quality | Cellular structure often preserved in detail |

| Examples of Petrified Wood | Arizona's Petrified Forest National Park (225 million years old) |

| Comparison to Fossilization | Petrification is a specific type of fossilization involving minerals |

| Human-Accelerated Petrification | Not feasible; requires natural geological processes over long periods |

Explore related products

$39.5

What You'll Learn

- Factors Affecting Petrification Speed: Climate, wood type, mineral content, and burial conditions influence petrification rate

- Initial Decay Process: Wood decays for years before minerals replace organic material, starting petrification

- Mineralization Timeline: Silica or calcite infiltration takes centuries to millions of years to complete

- Environmental Impact: Wet, mineral-rich environments accelerate petrification compared to dry, nutrient-poor settings

- Preservation Techniques: Human-assisted methods can shorten petrification time using controlled mineral exposure

Factors Affecting Petrification Speed: Climate, wood type, mineral content, and burial conditions influence petrification rate

Petrification, the process by which wood transforms into stone, is not a swift event but a geological marathon. The speed at which this occurs hinges on a delicate interplay of factors, each leaving its mark on the timeline. Climate, for instance, plays a pivotal role. In arid environments, where water is scarce, the minerals necessary for petrification struggle to permeate the wood, slowing the process to a crawl. Conversely, humid conditions accelerate mineralization, as water acts as a carrier for silica and other minerals, hastening the wood’s transformation.

Consider the wood type itself—a critical determinant of petrification speed. Softwoods, like pine, with their looser cell structures, allow minerals to infiltrate more rapidly, often petrifying faster than hardwoods such as oak. However, hardwoods, though slower to petrify, retain finer details due to their denser composition, resulting in more intricate fossilized specimens. For example, a pine log might fully petrify in 5,000 years under ideal conditions, while an oak log could take upwards of 10,000 years to achieve the same state.

Mineral content in the surrounding environment is another decisive factor. High concentrations of silica, the primary mineral involved in petrification, expedite the process. Areas rich in volcanic ash or sedimentary deposits often provide the ideal mineral-rich environment. In contrast, regions lacking these minerals may see petrification stall or proceed at a glacial pace. For instance, wood buried in silica-rich hot springs can petrify in as little as 1,000 years, while wood in mineral-poor soil might require 20,000 years or more.

Burial conditions round out this quartet of influences. Rapid burial under sediment shields wood from decay, preserving it long enough for minerals to take hold. Exposure to air and water, however, invites decomposition, which can halt petrification before it begins. Practical tip: if you’re attempting experimental petrification, bury wood in a mixture of sand and silica-rich clay, keeping it moist but not waterlogged, to mimic optimal burial conditions.

In essence, petrification speed is a symphony of variables, each contributing to the tempo of this ancient process. By understanding these factors—climate, wood type, mineral content, and burial conditions—one can better appreciate the remarkable journey from organic matter to stone, a transformation that spans millennia.

Drying Green Wood for Furniture: Essential Timing Tips for Perfect Results

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Initial Decay Process: Wood decays for years before minerals replace organic material, starting petrification

Wood decay is a silent, relentless process that begins the moment it is exposed to the elements. Fungi and bacteria, the unsung architects of decomposition, infiltrate the cellulose and lignin structures, breaking them down over years—sometimes decades. This initial phase is critical; without it, petrification cannot occur. The wood must first lose its organic integrity, becoming a porous scaffold ready to receive mineral-rich water. This decay period varies widely depending on environmental conditions: in humid, warm climates, it might take 10–20 years, while in arid regions, it could stretch to 50 years or more. Understanding this timeline is key for anyone studying or replicating the petrification process.

Consider the steps involved in this decay process as a natural preparation for transformation. First, the wood must be buried or submerged, shielding it from oxygen that would otherwise accelerate decomposition into nothingness. Next, water—often groundwater rich in minerals like silica, calcite, or pyrite—must permeate the wood, slowly dissolving its organic matter. This is not a quick soak but a gradual infiltration that can take years, even in ideal conditions. For instance, experiments simulating petrification in controlled environments show that mineralization begins only after the wood’s density drops below 50% of its original state, a threshold reached after prolonged decay.

A cautionary note: not all wood is destined for petrification. Most decayed wood simply disintegrates, lost to time. The difference lies in the presence of mineral-laden water and the absence of oxygen. Fossilization requires a specific set of circumstances—burial under sediment, consistent mineral flow, and stable environmental conditions. For enthusiasts attempting to replicate this process, patience is paramount. Accelerating decay artificially, such as by using acids or heat, often destroys the wood’s structure, rendering it unsuitable for mineralization. Natural decay, though slow, preserves the cellular framework necessary for petrification.

Comparing natural and artificial petrification highlights the importance of this initial decay phase. In nature, the process is unhurried, allowing minerals to replace organic material cell by cell, preserving intricate details like growth rings or bark patterns. In contrast, lab-induced petrification often lacks this precision, resulting in a more uniform, less detailed fossil. For example, wood petrified in Yellowstone’s hot springs over millennia retains stunning clarity, while artificially petrified samples often appear cloudy or distorted. This underscores the value of letting decay run its course, a lesson for both scientists and hobbyists.

In practical terms, if you’re attempting to petrify wood, start by selecting a dense, resinous species like pine or oak, which decay more slowly and retain structure longer. Bury it in a mineral-rich environment, such as near a natural spring or in sediment with high silica content. Monitor moisture levels—too dry, and decay stalls; too wet, and the wood may rot away. Expect to wait at least a decade before mineralization becomes visible, and several more before the wood is fully petrified. This is not a project for the impatient, but the reward—a permanent, stone-like replica of organic material—is a testament to nature’s patience and precision.

Traeger 575 Wood Pellet Burn Time: How Long Do They Last?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$6.99

Mineralization Timeline: Silica or calcite infiltration takes centuries to millions of years to complete

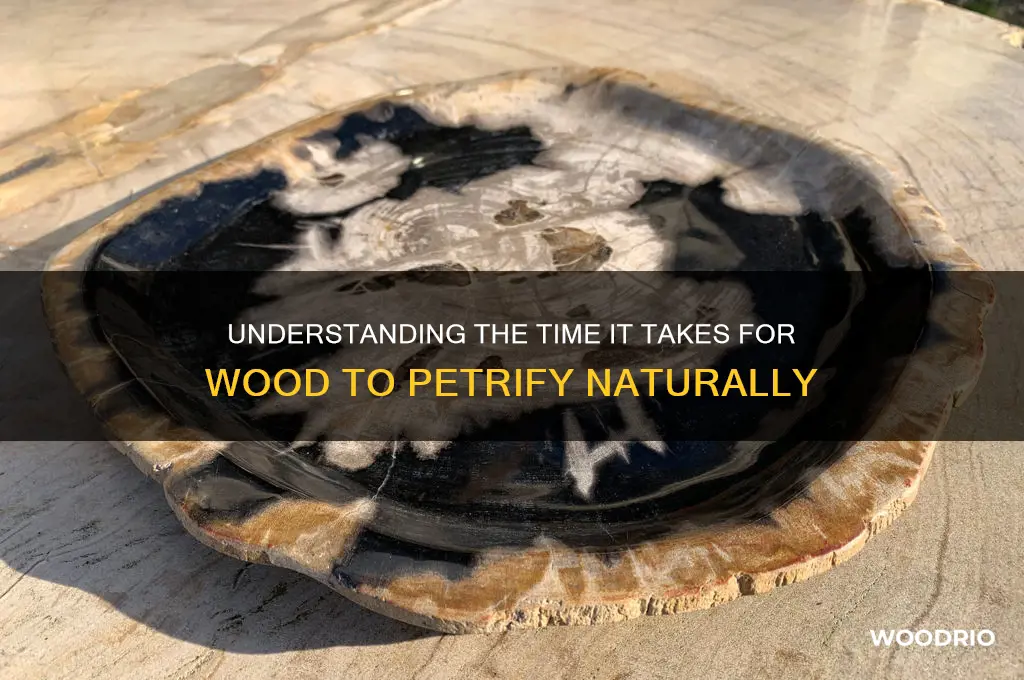

The process of wood petrification, or mineralization, is a testament to nature's patience, unfolding over centuries to millions of years. Silica and calcite, the primary minerals involved, infiltrate the wood's cellular structure, replacing organic matter with stone in a slow, meticulous dance. This transformation doesn't happen overnight; it requires specific conditions—buried environments, mineral-rich waters, and geological stability—to proceed. For instance, the famous petrified forests in Arizona showcase wood that began its journey over 200 million years ago, a timeline that dwarfs human comprehension of time.

Analyzing the mineralization timeline reveals a stark contrast between human impatience and geological endurance. Silica infiltration, often driven by groundwater rich in dissolved quartz, progresses at a rate of millimeters per thousand years. Calcite, on the other hand, may move slightly faster in carbonate-rich environments but still demands eons to complete the process. These rates are influenced by factors like temperature, pressure, and mineral availability. For hobbyists or researchers attempting artificial petrification, accelerating this process requires controlled environments and chemical solutions, such as sodium silicate baths, but even then, weeks or months are needed to achieve partial results—a far cry from the natural timeline.

Persuasively, understanding this timeline underscores the rarity and value of petrified wood. Each piece is a geological artifact, preserving ancient ecosystems and climatic conditions. For collectors, knowing that a small specimen took millions of years to form adds profound significance to its ownership. Practically, this knowledge also guides conservation efforts, emphasizing the need to protect natural petrification sites from over-extraction. After all, once destroyed, these formations cannot be replenished within human timescales.

Comparatively, the mineralization of wood contrasts sharply with other fossilization processes. While amber traps organisms in resin within decades, and coal forms from compressed vegetation over millions of years, petrification uniquely preserves the wood's original structure in exquisite detail. This distinction highlights the role of silica and calcite as nature's sculptors, working at a pace that ensures every cell, every ring, is immortalized in stone. For educators, this comparison offers a compelling narrative to illustrate Earth's diverse preservation mechanisms.

Descriptively, imagine a fallen tree in a prehistoric riverbed, slowly buried by sediment. Over millennia, groundwater seeps through, carrying silica or calcite particles that infiltrate the wood's pores. As organic material decays, minerals crystallize, layer by layer, until the wood is entirely replaced. The result? A stone replica so detailed that growth rings and even cellular structures remain visible. This process, though glacially slow, produces artifacts of breathtaking beauty and scientific value. For enthusiasts, witnessing even a fraction of this transformation—whether in nature or a lab—offers a tangible connection to deep time.

Exploring Spooky Woods: Time Estimates for a Chilling Adventure

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Environmental Impact: Wet, mineral-rich environments accelerate petrification compared to dry, nutrient-poor settings

The rate at which wood petrifies is not uniform across environments. Wet, mineral-rich settings, such as those found in ancient riverbeds or volcanic ash deposits, significantly accelerate the process. In these conditions, groundwater saturated with minerals like silica, calcite, and pyrite permeates the wood, replacing organic cells with crystalline structures at a molecular level. For instance, the petrified forests of Arizona, formed over 200 million years ago, owe their preservation to a combination of volcanic ash and mineral-laden water, which transformed wood into quartz-rich stone in as little as 1,000 to 10,000 years.

In contrast, dry, nutrient-poor environments slow petrification to a near halt. Deserts, for example, lack the moisture and minerals necessary to facilitate the cell-by-cell replacement of organic material. Wood in such settings may mummify or degrade over centuries but rarely petrifies. The Atacama Desert, one of the driest places on Earth, contains wood fragments that are thousands of years old yet remain largely organic due to the absence of water and minerals. This stark comparison highlights the critical role of environmental conditions in determining the fate of wood over geological timescales.

To replicate petrification in a controlled setting, consider the following steps. First, immerse the wood in a solution of silica-rich water, such as diluted sodium silicate (water glass), at a concentration of 10-20%. Maintain a temperature of 60-80°C to accelerate mineral penetration. Over weeks to months, the wood will gradually harden as silica precipitates within its cellular structure. For a more natural approach, bury the wood in a mineral-rich soil mixture, ensuring consistent moisture levels through regular watering. While this method takes years, it mimics the conditions of wet, mineral-rich environments and yields authentic petrification.

However, not all wood is equally suited for petrification. Dense, resinous woods like pine or cedar are less ideal due to their natural resistance to decay and mineral infiltration. Instead, choose softer woods like oak or maple, which have more porous structures that readily absorb minerals. Additionally, avoid environments with high acidity or salinity, as these can degrade the wood before petrification occurs. By selecting the right wood and environment, you can significantly influence the speed and success of the petrification process.

The environmental impact on petrification extends beyond scientific curiosity—it has practical implications for archaeology, conservation, and even art. Understanding these factors allows researchers to predict where petrified wood is likely to be found and how to preserve it. For enthusiasts, it offers a roadmap for creating petrified wood specimens, whether for educational displays or personal collections. By harnessing the power of wet, mineral-rich environments, we can both study the past and craft enduring artifacts for the future.

Creosote in Wood: Understanding Its Longevity and Preservation Effects

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Preservation Techniques: Human-assisted methods can shorten petrification time using controlled mineral exposure

Wood petrification, a process typically spanning millennia, can be significantly accelerated through human-assisted preservation techniques that leverage controlled mineral exposure. By mimicking the natural conditions that lead to fossilization, these methods condense geological timescales into manageable periods, often measured in years rather than epochs. Silica, calcium carbonate, and other minerals are introduced in precise concentrations to infiltrate the wood’s cellular structure, replacing organic matter with durable stone-like material. This approach not only preserves the wood’s original texture and shape but also enhances its longevity for scientific study, artistic display, or historical preservation.

To initiate the process, wood samples are first treated to remove organic compounds that could decay or hinder mineral absorption. Submersion in a solution of diluted acetic acid (vinegar) or hydrogen peroxide can effectively clean the wood, preparing it for mineral infiltration. Once cleaned, the wood is placed in a saturated solution of silica gel or calcium chloride, with concentrations ranging from 10% to 25% depending on the desired rate of petrification. Temperature and pH levels are carefully monitored—ideally maintained between 20°C and 30°C and a neutral pH—to optimize mineral uptake. Over weeks to months, the wood gradually hardens as minerals crystallize within its cellular framework, achieving a petrified state far faster than natural processes allow.

A comparative analysis reveals the advantages of human-assisted petrification over natural methods. While natural petrification relies on chance encounters with mineral-rich groundwater and stable geological conditions, controlled techniques ensure consistency and predictability. For instance, a study published in the *Journal of Archaeological Science* demonstrated that wood treated with a 15% silica solution achieved 70% mineralization within six months, a process that would naturally take over 10,000 years. This efficiency makes human-assisted petrification particularly valuable for preserving archaeological artifacts or creating durable replicas for educational purposes.

Practical applications of accelerated petrification extend beyond scientific preservation. Artists and craftsmen are increasingly adopting these techniques to create unique, stone-like sculptures and decorative pieces. For hobbyists, a simplified method involves soaking wood in a mixture of waterglass (sodium silicate) and food-grade phosphoric acid, which initiates mineralization without requiring laboratory-grade precision. However, caution must be exercised to avoid overexposure, as excessive mineralization can cause the wood to become brittle or lose fine details. Regular monitoring and gradual adjustments to the mineral solution’s concentration are essential to achieving the desired balance between preservation and aesthetic appeal.

In conclusion, human-assisted petrification techniques offer a revolutionary approach to preserving wood, blending scientific precision with practical creativity. By controlling mineral exposure, these methods not only shorten the petrification timeline but also open new possibilities for art, education, and historical conservation. Whether for professional research or personal projects, understanding and applying these techniques can transform organic wood into enduring, mineralized masterpieces.

PVA Drying Time on Wood: Factors Affecting Cure Speed and Tips

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Petrification is the process where organic wood is gradually replaced by minerals, typically silica, turning it into a stone-like material while retaining its original structure.

Natural petrification typically takes thousands to millions of years, depending on environmental conditions such as mineral-rich water, consistent pressure, and stable temperatures.

Yes, under controlled laboratory conditions, wood can be petrified in a matter of months to years by accelerating the mineralization process using high-pressure and high-temperature treatments.

The speed of petrification depends on factors like the presence of mineral-rich water, pH levels, temperature, pressure, and the type of wood. Harder woods with denser cell structures may petrify more slowly.