The process of wood turning into stone, known as petrification, is a fascinating natural phenomenon that occurs over an incredibly long period, typically spanning millions of years. It begins when wood becomes buried under sediment, shielding it from decay and allowing minerals, often silica, to gradually infiltrate its cellular structure. Over time, these minerals replace the organic material, preserving the wood’s original texture and structure while transforming it into a stone-like substance. Factors such as the presence of mineral-rich water, stable environmental conditions, and the absence of oxygen accelerate this process, but even under ideal circumstances, petrification requires immense geological timescales, making it a rare and awe-inspiring example of Earth’s transformative power.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Process Name | Permineralization or Fossilization |

| Time Required | Thousands to millions of years (varies based on conditions) |

| Key Conditions | Anaerobic environment (lack of oxygen), burial in sediment, presence of mineral-rich water |

| Minerals Involved | Silica (most common), calcite, pyrite, iron oxides |

| Resulting Material | Petrified wood (chalcedony or quartz-based) |

| Preservation Level | Cellular structure often preserved in detail |

| Common Locations | Volcanic ash deposits, riverbeds, swamps |

| Examples | Petrified Forest National Park (Arizona, USA) |

| Factors Affecting Speed | Temperature, pH, mineral concentration, depth of burial |

| Typical Duration Range | 10,000 to 100 million years |

| End Product Appearance | Hard, stone-like material with original wood grain patterns visible |

Explore related products

$39.5

What You'll Learn

- Petrification Process Overview: How minerals replace wood cells over time, turning organic matter into stone

- Timeframe for Petrification: Typically millions of years, depending on environmental conditions and mineral availability

- Key Environmental Factors: Requires burial in sediment, water rich in minerals, and absence of oxygen

- Types of Wood Petrification: Silicification (silica) and calcification (calcium carbonate) are common processes

- Examples of Petrified Wood: Famous sites like Arizona’s Petrified Forest showcase fully transformed wood fossils

Petrification Process Overview: How minerals replace wood cells over time, turning organic matter into stone

Wood doesn't simply dissolve and transform into stone overnight. The petrification process is a geological ballet, a slow and meticulous replacement of organic matter with minerals, molecule by molecule. Imagine a tree, fallen and buried under sediment. Groundwater, rich in dissolved minerals like silica, calcium, and iron, seeps through the wood. Over millennia, these minerals infiltrate the cellular structure, filling the voids left by decaying plant material.

Imagine a microscopic sculptor, patiently carving away the organic original and replacing it with a mineral replica, preserving the wood's intricate cellular details in stone.

This process, known as permineralization, is a race against time. The wood must be buried quickly, shielding it from oxygen and bacteria that would hasten decay. The surrounding environment plays a crucial role. Volcanic ash, for instance, provides a rich source of silica, accelerating petrification. Conversely, a lack of minerals or exposure to air can halt the process entirely. Think of it as a delicate recipe: the right ingredients (minerals), the right conditions (burial, lack of oxygen), and a *lot* of time.

Unlike baking a cake, however, this recipe takes millions of years.

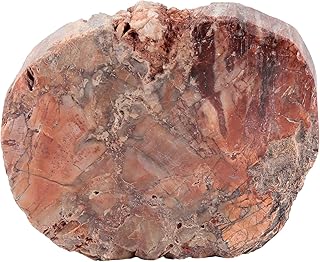

The resulting petrified wood is a testament to this patient transformation. Each piece is unique, its color and pattern dictated by the specific minerals present during its formation. A high iron content might yield reddish hues, while manganese can produce pinks and blacks. The original wood's structure, from growth rings to cellular details, is often remarkably preserved, offering a window into ancient ecosystems. Holding a piece of petrified wood is like holding a time capsule, a tangible connection to a world long gone.

While the process itself is fascinating, it's important to remember that petrification is incredibly rare. The conditions required are specific and uncommon. Most wood simply decays, returning its carbon to the cycle of life. Petrified wood, therefore, is a precious reminder of the Earth's geological history, a glimpse into the slow, relentless march of time that shapes our planet.

Drying Oak Wood: Essential Timeframe and Techniques for Perfect Results

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$29.99

Timeframe for Petrification: Typically millions of years, depending on environmental conditions and mineral availability

Petrification, the process by which wood transforms into stone, is a geological marvel that demands specific conditions and vast stretches of time. Unlike rapid fossilization methods, such as amber formation, petrification unfolds over millions of years. This timeframe is not arbitrary; it hinges on the slow, meticulous replacement of organic material with minerals, molecule by molecule. For instance, the petrified forests of Arizona showcase trees that began their transformation over 200 million years ago, a testament to the process’s glacial pace.

Environmental conditions play a pivotal role in determining how long petrification takes. Ideal settings include waterlogged environments, like ancient swamps or riverbeds, where sediment buries wood quickly, shielding it from decay. The presence of mineral-rich groundwater is equally critical, as it supplies the silica, calcite, or pyrite necessary for the wood’s cellular structure to be replicated in stone. Without these conditions, wood simply decomposes, leaving no trace. For example, wood buried in arid deserts or exposed to oxygen rarely petrifies, as it lacks the moisture and minerals required for the process.

Mineral availability acts as the catalyst for petrification, dictating both its speed and outcome. Silica, the most common mineral involved, infiltrates wood cells through groundwater, gradually hardening into quartz. This process, known as permineralization, can take anywhere from 10,000 to several million years, depending on the concentration of minerals and the rate of groundwater flow. In rare cases, iron oxides or carbonates may dominate, altering the final color and composition of the petrified wood. Practical tip: Collectors seeking vibrant specimens should look for pieces with high iron content, which often results in red or yellow hues.

Comparing petrification to other fossilization processes highlights its uniqueness. While coal formation takes millions of years under high pressure and heat, and amber traps organisms in resin within centuries, petrification stands out for its mineral-driven precision. Each step—burial, mineral infiltration, and hardening—must occur sequentially, with no room for interruption. This makes petrified wood not just a relic of the past but a geological time capsule, preserving details like tree rings and cellular structures with astonishing clarity.

For enthusiasts or researchers, understanding the timeframe for petrification offers practical insights. While creating petrified wood artificially is possible through accelerated mineralization techniques, it still requires years, not days. Laboratories use high-pressure, mineral-rich solutions to replicate natural conditions, but even these methods pale in comparison to the Earth’s patient craftsmanship. Takeaway: Petrification is a reminder of nature’s slow, relentless artistry, where time and minerals conspire to turn the ephemeral into the eternal.

Wood Finish Drying Time: Factors Affecting Cure and Dry Speed

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Key Environmental Factors: Requires burial in sediment, water rich in minerals, and absence of oxygen

The transformation of wood into stone, a process known as petrification, hinges on specific environmental conditions that act as catalysts for this remarkable metamorphosis. Among these, burial in sediment stands as the initial and perhaps most critical step. Sediment acts as a protective blanket, shielding the wood from the erosive forces of wind, water, and sunlight. This burial process must occur swiftly to prevent the wood from decaying completely. For instance, trees that fall into riverbeds or are quickly covered by volcanic ash have a higher likelihood of beginning the petrification journey. The depth of burial matters too; deeper layers provide more consistent pressure and protection, though not so deep as to crush the wood’s cellular structure entirely.

Once buried, the presence of water rich in minerals becomes the next essential factor. This water, often groundwater percolating through mineral-laden rock, carries dissolved silica, calcite, pyrite, and other minerals. The concentration of these minerals is crucial; water with a mineral content of at least 50 parts per million (ppm) of silica is ideal for petrification. As this mineral-rich water seeps through the buried wood, it begins to replace the organic material cell by cell. Over time, the wood’s original structure is replicated in stone, preserving intricate details like growth rings and even cellular patterns. This process, known as permineralization, can take thousands to millions of years, depending on the mineral content and flow rate of the water.

Equally vital is the absence of oxygen, which prevents the wood from fully decomposing. In an oxygen-rich environment, fungi, bacteria, and other decomposers would break down the wood’s cellulose and lignin, leaving nothing behind to be fossilized. Anaerobic conditions, however, halt this decay. Such environments are often found in deep sedimentary layers or underwater, where oxygen is scarce. For example, wood buried in peat bogs or at the bottom of lakes can remain preserved for centuries, awaiting the influx of mineral-rich water to initiate petrification.

To summarize, the petrification of wood requires a precise interplay of burial in sediment, exposure to mineral-rich water, and an oxygen-free environment. Each factor plays a distinct role: sediment protects, mineral-rich water transforms, and the absence of oxygen preserves. While the process is slow, often spanning millennia, understanding these conditions allows us to identify potential sites for fossilized wood and appreciate the rarity of such natural wonders. Practical tips for enthusiasts include seeking areas with volcanic history or sedimentary rock formations, where these conditions are more likely to have occurred.

Durability of Wooden Spoons: Lifespan and Care Tips Revealed

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Types of Wood Petrification: Silicification (silica) and calcification (calcium carbonate) are common processes

Wood petrification, the transformation of organic material into stone, is a geological marvel driven by two primary processes: silicification and calcification. Each method leaves a distinct imprint on the fossilized wood, offering clues to the environmental conditions that facilitated its preservation. Silicification, the more common of the two, occurs when silica-rich groundwater permeates the wood’s cellular structure, replacing organic matter with quartz or chalcedony. This process results in fossils that retain intricate details, such as growth rings and cellular patterns, often with a glassy or crystalline appearance. For instance, the petrified forests of Arizona showcase silicified wood that formed over millions of years, where ancient trees were buried under volcanic ash and exposed to silica-laden waters.

Calcification, while less frequent, involves the infiltration of calcium carbonate into the wood, typically in environments rich in limestone or marine sediments. This process yields fossils with a more opaque, chalky texture, often lacking the fine detail preserved by silicification. Examples of calcified wood are found in areas like the Black Hills of South Dakota, where calcium-rich waters replaced the organic material in a slower, more diffuse manner. The choice between silicification and calcification depends largely on the mineral composition of the surrounding sediment and groundwater, with silica dominating in volcanic or sandy environments and calcium carbonate prevailing in carbonate-rich settings.

Understanding these processes is crucial for geologists and paleontologists, as the type of petrification can reveal the ancient environment in which the wood was preserved. Silicified wood, for instance, often indicates a history of volcanic activity or sedimentation in silica-rich basins, while calcified wood suggests a marine or limestone-dominated landscape. Practical applications extend to collectors and educators, who can use the distinct characteristics of each type to identify and interpret fossilized wood specimens.

For those interested in witnessing these processes firsthand, visiting sites like the Petrified Forest National Park in Arizona or the Florissant Fossil Beds in Colorado can provide tangible examples of silicification. Conversely, exploring limestone quarries or marine fossil beds may yield rarer instances of calcified wood. Preserving such specimens requires careful handling, as both types are susceptible to weathering and erosion once exposed to the elements.

In conclusion, silicification and calcification are not merely scientific curiosities but windows into Earth’s history, each telling a story of the conditions that transformed wood into stone. By recognizing their unique signatures, we gain deeper insights into the geological forces that shape our planet and the life forms that once inhabited it. Whether for academic study or personal fascination, understanding these processes enriches our appreciation of the natural world.

Mastering Wood Transfers: Mod Podge Drying Time Explained

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Examples of Petrified Wood: Famous sites like Arizona’s Petrified Forest showcase fully transformed wood fossils

The process of wood transforming into stone, known as petrification, is a geological marvel that takes millions of years. One of the most striking examples of this phenomenon is found in Arizona’s Petrified Forest National Park, where ancient trees have been fully mineralized into quartz-rich fossils. These specimens, dating back over 225 million years, retain intricate details of their original structure, from bark patterns to growth rings, offering a window into Earth’s prehistoric past. The park’s vibrant, crystalline wood fossils are a testament to the slow, meticulous work of nature, where silica-rich water seeped into buried logs, replacing organic material cell by cell with minerals like quartz, calcite, and pyrite.

To understand the scale of this transformation, consider the conditions required for petrification. Wood must be buried quickly, often by sediment or volcanic ash, to shield it from decay. Over time, groundwater rich in dissolved minerals permeates the wood, gradually replacing its organic matter with stone. This process is not uniform; some fossils in Arizona’s Petrified Forest exhibit a rainbow of colors due to trace minerals like manganese, iron, and copper, which create hues of purple, yellow, and red. The park’s Rainbow Forest, for instance, is a vivid showcase of this mineral diversity, attracting geologists, paleontologists, and tourists alike.

While Arizona’s Petrified Forest is perhaps the most famous site, it is not the only one. Locations like the Yellowstone Petrified Forest in Wyoming and the Lesbos Petrified Forest in Greece offer additional examples of this ancient process. Each site tells a unique story of its geological history, influenced by local mineral compositions and environmental conditions. For instance, the Lesbos Forest’s fossils are primarily composed of silica and calcite, reflecting the island’s volcanic past. These global examples underscore the universality of petrification, though the specific outcomes vary based on regional factors.

For those interested in witnessing petrified wood firsthand, visiting these sites requires careful planning. Arizona’s Petrified Forest, for example, spans over 200 square miles, with designated trails and viewing areas to protect the fragile fossils. Visitors are strictly prohibited from removing any specimens, as theft and vandalism have historically threatened the park’s resources. Instead, the park encourages exploration and education, offering guided tours and interpretive exhibits to deepen understanding of the petrification process. Practical tips include wearing sturdy shoes for uneven terrain, carrying water, and visiting during cooler months to avoid Arizona’s extreme heat.

Beyond their aesthetic appeal, petrified wood fossils serve as invaluable scientific tools. They provide insights into ancient ecosystems, climate conditions, and even the evolution of plant life. For instance, the presence of conifer fossils in Arizona’s Petrified Forest suggests a once lush, tropical environment, starkly different from today’s arid landscape. By studying these fossils, researchers can reconstruct past environments and track changes over millions of years. This makes sites like the Petrified Forest not just natural wonders but also living laboratories for understanding Earth’s history. Whether for scientific study or personal awe, these fully transformed wood fossils remind us of the enduring power of geological processes.

Drying Cord Wood: Understanding the Time It Takes to Season Properly

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The process of wood turning to stone, known as petrification, typically takes thousands to millions of years. It depends on factors like mineral availability, water flow, and environmental conditions.

Petrification requires the wood to be buried in sediment rich in minerals, protected from decay by oxygen, and exposed to groundwater carrying dissolved minerals like silica. Over time, these minerals replace the organic material in the wood.

While petrification usually takes millions of years, accelerated processes in laboratory settings or unique natural environments (e.g., hot springs) can reduce the time to centuries or decades. However, these are exceptions, and natural petrification remains a slow process.