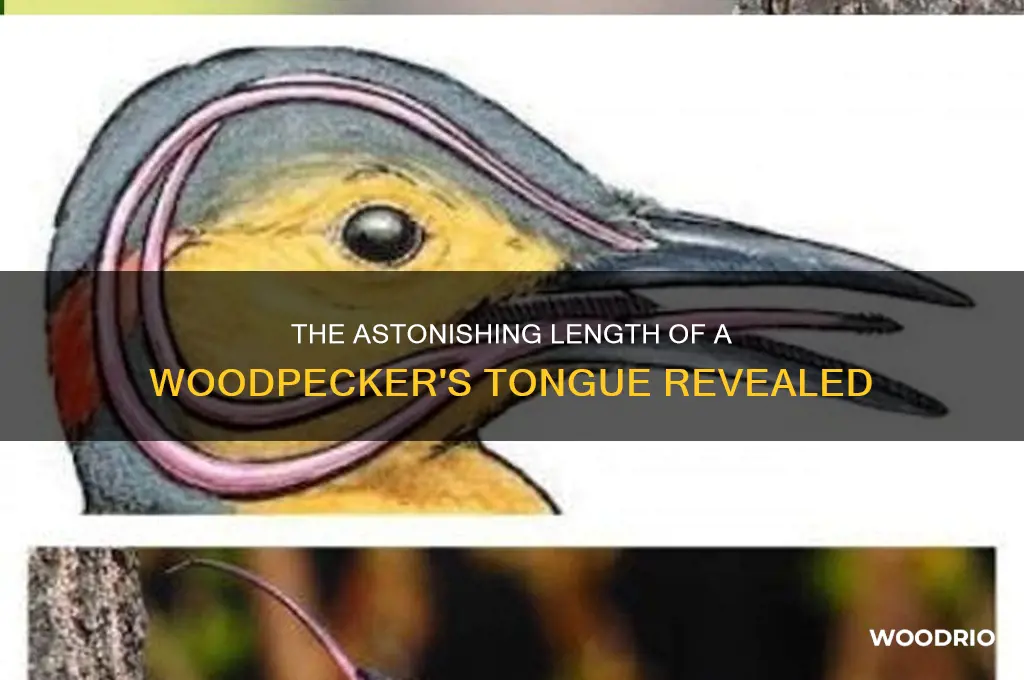

Woodpeckers are renowned for their remarkable adaptations, and one of the most fascinating features is their tongue, which plays a crucial role in their feeding habits. The length of a woodpecker’s tongue varies significantly among species, with some having tongues that can extend up to 4 inches beyond the tip of their bill. For instance, the Red-bellied Woodpecker has a relatively short tongue, while the Northern Flicker boasts a tongue that can reach astonishing lengths, often exceeding the length of its entire body when fully extended. This elongated tongue, often barbed and sticky, allows woodpeckers to extract insects from deep within tree bark with incredible precision. Understanding the length and function of a woodpecker’s tongue provides valuable insights into their evolutionary adaptations and survival strategies in their natural habitats.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Tongue Length (Average) | 3 to 4 inches (7.6 to 10 cm) |

| Tongue Length (Maximum) | Up to 6 inches (15 cm) in some species like the Red-bellied Woodpecker |

| Tongue Wrapping Ability | Can wrap around the skull, extending beyond the tip of the bill |

| Tongue Structure | Barbed tip for gripping insects, sticky saliva for extraction |

| Tongue Function | Extracting insects from deep crevices in trees |

| Tongue Musculature | Hyoid bone extends and retracts the tongue with elastic properties |

| Tongue Protrusion | Can protrude far beyond the bill tip |

| Tongue Adaptation | Specialized for foraging in tree bark |

| Tongue Comparison to Body Size | Tongue length can be up to 1.5 times the bird's bill length |

| Tongue Role in Feeding | Primary tool for catching and extracting prey from wood |

Explore related products

$9.99 $10.79

What You'll Learn

Tongue Length Variation by Species

Woodpeckers, with their remarkable tongue lengths, showcase one of nature’s most fascinating adaptations. Among the most striking examples is the red-cockaded woodpecker, whose tongue extends up to 4 inches, nearly double the length of its bill. This extraordinary reach allows it to extract insects from deep within tree bark, a feat that underscores the species’ evolutionary ingenuity. Such specialization highlights how tongue length is not merely a physical trait but a critical survival tool, finely tuned to the woodpecker’s ecological niche.

Consider the black-backed woodpecker, whose tongue length is slightly shorter but equally impressive, measuring around 2 to 3 inches. This species relies on its tongue to probe decaying wood for wood-boring beetle larvae, a diet that demands precision and depth. The variation in tongue length between species like these is not arbitrary; it reflects distinct feeding strategies and habitat preferences. For instance, woodpeckers that feed on sap may have shorter tongues, while those targeting deep-dwelling insects require the extra length to secure their meals.

To understand these variations, examine the anatomy of the woodpecker’s tongue. It wraps around the skull, anchored by a specialized bone called the hyoid, which acts as a slingshot mechanism. This design enables the tongue to extend far beyond the beak, a feature unique to woodpeckers. For practical observation, compare the tongue lengths of different species in field guides or scientific studies. Note how the pileated woodpecker, with a tongue reaching up to 4 inches, contrasts with the smaller downy woodpecker, whose tongue is proportionally shorter.

From a comparative perspective, the tongue length of woodpeckers far exceeds that of most birds, which typically have tongues less than an inch long. This disparity emphasizes the woodpecker’s specialized role as a bark forager. For enthusiasts or researchers, measuring tongue length in preserved specimens or through observational studies can provide insights into species-specific behaviors. For example, longer tongues correlate with deeper foraging, while shorter ones may indicate a preference for surface-level food sources.

In conclusion, the variation in woodpecker tongue lengths is a testament to the precision of evolutionary adaptation. Each species’ tongue is tailored to its dietary needs, whether extracting insects from deep crevices or lapping up sap. By studying these differences, we gain a deeper appreciation for the intricate relationship between form and function in the natural world. For those intrigued by this topic, exploring species-specific data or observing woodpeckers in their habitats can offer a tangible connection to these remarkable adaptations.

Charcoal vs. Wood: Which Burns Longer for Your Fire Needs?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$3.99

Purpose of the Long Tongue

Woodpeckers possess tongues that can extend up to four inches beyond the tip of their bill, a length that seems disproportionate to their body size. This remarkable adaptation serves a critical purpose in their survival and feeding habits. The tongue acts as a specialized tool, allowing woodpeckers to extract insects from deep within tree bark crevices. Its length, combined with a sticky saliva, ensures that even the most elusive prey cannot escape. This anatomical feature is not merely a curiosity but a testament to the precision of evolutionary design.

Consider the mechanics of a woodpecker’s feeding behavior. When a woodpecker drills into a tree, it creates a narrow, deep hole to access larvae or insects. The tongue, coiled in a specialized bone structure called the hyoid, unfurls with astonishing speed and accuracy. This process is not just about reaching the prey; it’s about doing so efficiently, minimizing energy expenditure while maximizing food intake. For birdwatchers or researchers, observing this behavior provides insight into the intricate relationship between form and function in nature.

From a comparative perspective, the woodpecker’s tongue stands out even among birds with elongated tongues. Hummingbirds, for instance, use their long tongues for nectar extraction, but the woodpecker’s tongue is uniquely adapted for predation. Its barbed tip and sticky surface are tailored to grasp and extract insects, a feature hummingbirds lack. This specialization highlights how environmental pressures shape anatomical adaptations differently across species. Understanding these distinctions can enrich educational discussions on biodiversity and evolutionary biology.

Practical applications of this knowledge extend beyond academic curiosity. For instance, conservationists can use insights into woodpecker feeding habits to design better habitats. Ensuring trees with deep bark crevices are preserved can support woodpecker populations by providing ample food sources. Similarly, educators can create engaging lessons by demonstrating the tongue’s mechanics using simple models, fostering a deeper appreciation for wildlife adaptations in younger audiences.

In conclusion, the woodpecker’s long tongue is a marvel of adaptation, finely tuned to its ecological niche. Its length, structure, and function illustrate the interplay between survival needs and evolutionary responses. By studying this feature, we gain not only scientific knowledge but also practical tools for conservation and education, underscoring the broader significance of understanding even the smallest details in nature.

How Long Does Wood Finish Smell Last? A Complete Guide

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Tongue Wrapping Around Skull

Woodpeckers possess one of the most extraordinary anatomical adaptations in the animal kingdom: their tongues wrap entirely around their skulls. This isn't merely a curiosity—it’s a survival mechanism. A woodpecker’s tongue, which can extend up to 4 inches (or 10 cm) in some species, is anchored at the base of the beak, loops around the back of the skull, and reattaches under the skin near the right nostril. This unique structure acts as a shock absorber, protecting the brain from the concussive forces generated by their rapid pecking, which can reach speeds of 15 miles per hour (24 km/h). Without this adaptation, woodpeckers would likely suffer severe brain injuries from their relentless drilling into trees.

To visualize this, imagine a seatbelt for the brain. The tongue’s elasticity and length distribute the impact energy, much like how a car’s crumple zones reduce collision force. This design is so effective that engineers have studied it for inspiration in developing protective gear, such as helmets for athletes and soldiers. For instance, a 2014 study in the *PLOS ONE* journal highlighted how the woodpecker’s skull and tongue mechanics could inform concussion prevention technology. If you’re designing safety equipment, consider mimicking this natural shock-absorbing system—it’s a proven model with millions of years of evolutionary testing.

From a practical standpoint, understanding this adaptation can also aid in wildlife rehabilitation. If you encounter an injured woodpecker, avoid handling it roughly, as its skull and tongue are finely tuned for impact resistance, not human interference. Instead, place the bird in a secure, padded container and contact a licensed wildlife rehabilitator immediately. Remember, woodpeckers’ tongues aren’t just long—they’re a critical part of their anatomy, and mishandling can exacerbate injuries.

Comparatively, other birds lack this skull-wrapping tongue feature, which underscores its uniqueness. While hummingbirds have long tongues for nectar feeding, they don’t serve a protective function. The woodpecker’s tongue is a dual-purpose tool: it’s both a weapon against wood-boring insects and a shield for its brain. This duality makes it a fascinating subject for both biologists and biomimicry enthusiasts. Next time you see a woodpecker, appreciate not just its rhythmic drumming but the marvel of engineering hidden within its head.

Wood Dye Drying Time: Factors Affecting Quick and Efficient Results

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Tongue Muscle Structure

Woodpeckers possess remarkably elongated tongues, often exceeding the length of their bills, which can extend deep into tree cavities to extract insects. This extraordinary adaptation is underpinned by a unique tongue muscle structure, a marvel of evolutionary engineering. Unlike humans, whose tongues are primarily composed of intrinsic muscles confined within the organ, woodpeckers have a tongue that extends far beyond its muscular base, anchored to the skull and wrapped around the brain. This structure allows for both the length and the retraction force necessary for their feeding habits.

To understand the mechanics, consider the tongue’s muscular composition. The woodpecker’s tongue consists of a hyoid apparatus, a set of bones and muscles that extend from the base of the skull, loop around the back of the head, and attach to the tongue tip. This system acts like a spring-loaded mechanism, enabling the tongue to be stored compactly when not in use and rapidly extended when needed. The muscles are not merely elongated but are also highly elastic, composed of specialized fibers that can stretch and recoil with precision. This elasticity is crucial for the tongue’s ability to dart in and out of narrow crevices at high speeds.

From a comparative perspective, the woodpecker’s tongue muscle structure stands in stark contrast to that of other birds. Most avian species have shorter, less complex tongues, as their feeding habits do not require such extreme adaptations. For instance, hummingbirds rely on a grooved, extensible tongue for nectar feeding, but their muscle structure lacks the woodpecker’s hyoid loop. This comparison highlights how the woodpecker’s tongue is not just long but is also a product of specialized musculature tailored to its ecological niche.

Practical insights into this structure can inform biomimicry in engineering. For example, the woodpecker’s tongue inspires the design of retractable mechanisms in robotics, where compact storage and rapid deployment are essential. Engineers can mimic the hyoid apparatus to create systems that combine flexibility and strength, such as in endoscopic tools or search-and-rescue devices. Understanding the tongue’s muscle composition also sheds light on material science, suggesting the development of elastic polymers that replicate its stretch-and-recoil properties.

In conclusion, the woodpecker’s tongue muscle structure is a testament to nature’s ingenuity, blending length, elasticity, and precision to meet the demands of its feeding behavior. By dissecting this anatomical marvel, we gain not only biological insights but also practical applications that bridge the gap between biology and technology. Whether in robotics or material science, the woodpecker’s tongue serves as a blueprint for innovation, proving that even the most specialized adaptations can inspire universal solutions.

Understanding Natural Wood Off-Gassing: Duration and Factors Explained

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Role in Feeding Habits

Woodpeckers possess tongues that can extend up to four inches beyond the tip of their bill, a feature critical for extracting insects from deep within tree bark. This extraordinary length is not merely a curiosity but a highly specialized adaptation that directly supports their feeding habits. The tongue acts as a spear, tipped with a barbed end and coated in sticky saliva, allowing woodpeckers to impale and retrieve prey with precision. This mechanism is particularly effective for reaching larvae and beetles that burrow deep into wood, where a shorter tongue would be insufficient.

Consider the process: a woodpecker drills a hole into a tree, then inserts its tongue to capture hidden insects. The tongue’s length, combined with its flexibility and strength, ensures that even the most elusive prey is within reach. For example, the Red-bellied Woodpecker’s tongue wraps around the skull when retracted, a unique anatomical arrangement that maximizes reach without compromising the bird’s ability to close its beak. This adaptation highlights how tongue length is not just about size but also about functional design tailored to specific feeding behaviors.

To understand the role of tongue length in feeding habits, compare woodpeckers to other birds. While hummingbirds have long tongues for nectar extraction, their function is entirely different—they lap up liquid rather than spear solid prey. Woodpeckers, on the other hand, rely on their tongues as tools for extraction, a role that demands both length and structural complexity. This distinction underscores the evolutionary pressures shaping woodpecker tongues, which are optimized for a diet heavily reliant on wood-boring insects.

Practical observation of woodpecker feeding habits reveals the tongue’s importance in their daily survival. During breeding season, when energy demands are high, woodpeckers increase their foraging efforts, relying heavily on their tongues to secure protein-rich insects for themselves and their chicks. For bird enthusiasts or researchers, noting the frequency and depth of tongue use during feeding can provide insights into the bird’s health and environmental conditions. For instance, a woodpecker struggling to extract prey might indicate a scarcity of insects, prompting further investigation into habitat health.

In conclusion, the length of a woodpecker’s tongue is not just a biological oddity but a key component of its feeding strategy. Its design enables efficient prey capture, supporting the bird’s ecological role as both predator and forest health indicator. By studying this feature, we gain a deeper appreciation for the intricate relationships between anatomy, behavior, and environment in the natural world.

Durability of Wood Computer Desks: Lifespan and Maintenance Tips

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

A woodpecker's tongue can extend up to 4 inches (10 cm) beyond its beak, depending on the species.

Woodpeckers have long, sticky tongues to extract insects from deep within tree bark, aiding in their feeding habits.

No, tongue length varies by species. For example, the Red-bellied Woodpecker has a shorter tongue compared to the Northern Flicker, which has an exceptionally long one.

![[2 pack] KN FLAX Tongue Scraper [Medical Grade] Reduce Bad Breath Maintains Oral Care 100% BPA Free Metal Tongue Scraper, Tongue Cleaner for Adults and Kids, Easy to Use with Non-Synthetic Handle](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/71uvyz8JY4L._AC_UL320_.jpg)