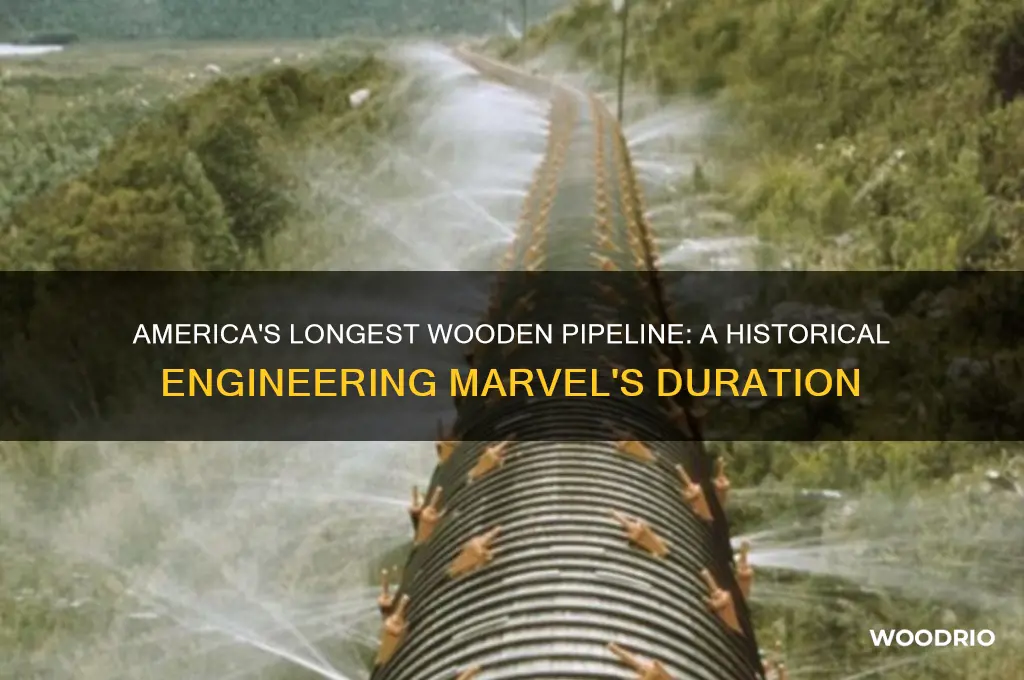

America's longest wooden pipeline, an engineering marvel of its time, stretched an impressive 122 miles from the oil fields of Titusville, Pennsylvania, to the refineries in Pittsburgh. Constructed in the late 19th century during the early days of the oil boom, this pipeline was a testament to the ingenuity and resourcefulness of the era. Made entirely from wooden logs, it played a crucial role in transporting crude oil efficiently before the advent of more durable materials like steel. Despite its vulnerability to leaks and decay, the wooden pipeline remained operational for several years, symbolizing a pivotal moment in the history of American infrastructure and the oil industry.

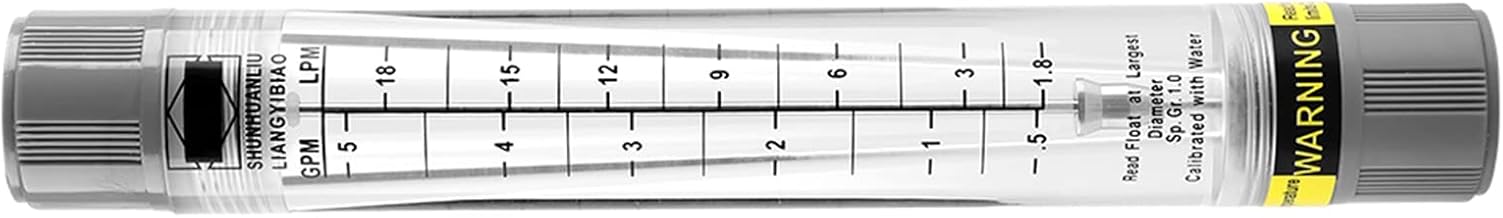

Explore related products

$13.45 $16.95

What You'll Learn

- Pipeline's Construction Date: When was America's longest wooden pipeline built and by whom

- Pipeline's Length: Exact measurement of the pipeline's total length in miles or feet

- Purpose and Use: Primary function and the resources it transported during its operation

- Operational Duration: How many years the wooden pipeline remained active and functional

- Historical Significance: Impact and legacy of the pipeline in American history and engineering

Pipeline's Construction Date: When was America's longest wooden pipeline built and by whom?

The construction of America's longest wooden pipeline is a fascinating chapter in the nation's industrial history, blending ingenuity with necessity. Built in the late 19th century, this pipeline stretched an impressive 120 miles, connecting the oil fields of Pennsylvania to the refineries and markets beyond. Its construction was a monumental feat, requiring thousands of wooden logs, meticulous engineering, and the labor of countless workers. This pipeline was not just a marvel of its time but also a testament to the resourcefulness of early American industrialists.

The exact construction date of this pipeline falls between 1865 and 1870, a period marked by rapid expansion in the oil industry. The man behind this ambitious project was George Bissell, a Yale chemistry professor turned oil entrepreneur. Bissell, along with his partner Edwin Drake, had already made history by drilling the first commercially successful oil well in Titusville, Pennsylvania, in 1859. Recognizing the need for efficient transportation, Bissell spearheaded the construction of the wooden pipeline to move crude oil from the wells to the railroads, revolutionizing the industry.

Building the pipeline was no small task. Workers had to source and cut thousands of hollowed-out logs, each carefully fitted together to create a seamless conduit. The logs were treated with pitch to prevent leaks and deterioration, though maintenance was constant due to the material’s susceptibility to rot and damage. Despite these challenges, the pipeline operated successfully for over a decade, playing a crucial role in establishing Pennsylvania as the epicenter of the early oil boom.

Comparing this wooden pipeline to modern steel pipelines highlights the evolution of engineering and materials science. While wooden pipelines were cheaper and easier to construct with the technology of the time, they were far less durable and efficient than their metal counterparts. The transition to steel pipelines in the late 19th century marked a turning point, offering greater longevity and capacity. Yet, the wooden pipeline remains a symbol of innovation, showcasing how early industrialists tackled logistical challenges with the resources available.

For history enthusiasts or those interested in industrial archaeology, tracing the remnants of this pipeline can offer a tangible connection to America’s past. While much of it has decayed or been reclaimed by nature, some sections and artifacts can still be found in Pennsylvania’s oil regions. Visiting sites like the Drake Well Museum provides insight into the pipeline’s construction and its impact on the oil industry. Understanding this history not only honors the pioneers of the past but also inspires appreciation for the technological advancements that followed.

Drying Wood Slices: Timeframe, Techniques, and Tips for Perfect Results

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Pipeline's Length: Exact measurement of the pipeline's total length in miles or feet

The exact measurement of America's longest wooden pipeline is a fascinating yet elusive detail in the annals of engineering history. While wooden pipelines were once a cornerstone of early American infrastructure, precise records of their lengths are often obscured by time and the ephemeral nature of their construction materials. However, historical accounts suggest that some wooden pipelines stretched for dozens of miles, serving critical roles in water and oil transportation. For instance, the wooden pipeline system in Pennsylvania’s oil regions during the late 19th century reportedly spanned over 50 miles, though exact figures vary depending on the source. This highlights the challenge of pinpointing precise measurements for structures that were often built in segments and frequently replaced or rerouted.

To measure the total length of a wooden pipeline accurately, one must consider the cumulative distance of all its segments, including bends, junctions, and extensions. Early engineers relied on rudimentary tools like chains and compasses, which could introduce discrepancies in their calculations. Modern historians and researchers often piece together these lengths using maps, company records, and archaeological evidence. For example, a pipeline might be documented as "approximately 30 miles long," but closer examination of its route could reveal an additional 5 miles of branching lines, bringing the total to 35 miles. This underscores the importance of cross-referencing multiple sources to arrive at a reliable figure.

When attempting to determine the exact length of a wooden pipeline, it’s crucial to account for the material’s limitations. Wooden pipes, typically made from hollowed-out logs, were prone to decay, leaks, and damage from environmental factors. As a result, pipelines were often repaired or extended, complicating efforts to measure their original or total length. Practical tips for researchers include studying historical photographs, consulting local archives, and collaborating with archaeologists who specialize in industrial sites. For instance, a pipeline documented as "20 miles long in 1880" might have been extended by 10 miles by 1890, requiring careful analysis of timelines and construction records.

Comparatively, wooden pipelines differ significantly from their modern steel counterparts, which are designed for precision and longevity. While a steel pipeline’s length can be measured with laser accuracy, wooden pipelines’ organic materials and makeshift construction methods make exact measurements more art than science. Take, for example, the wooden pipeline system in California’s early water distribution networks, which was estimated to span "over 40 miles" but lacked detailed blueprints. This ambiguity serves as a reminder that historical infrastructure often requires a blend of quantitative data and qualitative interpretation to understand its true scale.

In conclusion, determining the exact length of America’s longest wooden pipeline demands a meticulous approach, combining historical research, spatial analysis, and an appreciation for the challenges of early engineering. While precise figures may remain elusive, the effort to measure these pipelines sheds light on their remarkable scope and the ingenuity of those who built them. For enthusiasts and researchers alike, the pursuit of such measurements offers a tangible connection to a bygone era of American innovation.

Drying Time Guide: Elmer's Carpenter's Wood Filler Stainable Process

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$306.3

Purpose and Use: Primary function and the resources it transported during its operation

America's longest wooden pipeline, stretching over 120 miles from the oil fields of Titusville to the refineries in Pittsburgh, was a marvel of 19th-century engineering. Its primary function was to transport crude oil efficiently, addressing the logistical challenges of the burgeoning petroleum industry. Before its construction in the 1860s, oil was hauled by wagon or barge, a slow and costly process. The pipeline revolutionized this by enabling continuous, high-volume transport, directly fueling the industrial boom of the era.

The resources it transported were singularly focused: crude oil. This pipeline was not a multipurpose conduit but a dedicated artery for the liquid gold that powered the Industrial Revolution. Each section of the pipeline, crafted from wooden logs hollowed out and sealed with pitch, carried thousands of barrels daily. The system relied on gravity and later steam pumps to move the oil, showcasing early ingenuity in resource management. This single-resource focus highlights the pipeline’s role as a specialized tool, designed to meet the demands of a rapidly expanding economy.

Analyzing its operation reveals a delicate balance between innovation and limitation. Wooden pipelines were prone to leaks, rot, and blockages, requiring constant maintenance. Yet, they were cheaper and faster to construct than metal alternatives, making them a practical choice for the time. The pipeline’s lifespan was relatively short, replaced by more durable materials within decades, but its impact on oil transportation was profound. It laid the groundwork for modern pipeline systems, proving the viability of long-distance resource transport.

For those studying or replicating such systems, understanding the pipeline’s purpose and use offers practical insights. It underscores the importance of tailoring infrastructure to specific resources and economic contexts. Modern pipelines, though far more advanced, still reflect the core principles of efficiency and specialization pioneered by this wooden forerunner. By examining its design and function, we gain a blueprint for addressing contemporary challenges in resource transportation, from energy to water.

Tanalised Wood Durability: Lifespan, Maintenance, and Longevity Explained

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$24.99 $29.99

$8.99 $9.99

$11.99 $12.99

Operational Duration: How many years the wooden pipeline remained active and functional

The operational lifespan of America’s longest wooden pipeline, stretching over 41 miles from the Passaic River to Jersey City, spanned approximately 40 years, from its completion in 1855 to its decommissioning in the late 1890s. This remarkable duration highlights the durability of wooden infrastructure when properly maintained and protected. Constructed from hollowed-out logs coated in pitch and wrapped in metal bands, the pipeline withstood decades of continuous water flow, seasonal temperature fluctuations, and occasional repairs. Its longevity is a testament to 19th-century engineering ingenuity, particularly in an era predating modern materials like steel and concrete.

To understand the pipeline’s operational endurance, consider the maintenance practices that extended its lifespan. Workers regularly inspected the pipeline for leaks, rot, and insect damage, replacing compromised sections as needed. The use of pitch as a sealant and metal bands for structural reinforcement were critical to preventing water loss and structural failure. These proactive measures allowed the pipeline to remain functional despite being buried underground, where moisture and soil conditions could accelerate decay. For modern projects, this underscores the importance of routine maintenance and material selection in ensuring long-term infrastructure viability.

Comparatively, the wooden pipeline’s 40-year lifespan contrasts sharply with the shorter operational periods of early cast-iron or lead pipes, which often failed within 10–20 years due to corrosion and brittleness. Wooden pipelines, while less common today, offered a cost-effective and resource-efficient solution during the mid-1800s, leveraging abundant timber supplies. This historical example challenges the assumption that traditional materials are inherently inferior to modern alternatives, especially when designed and maintained with care. It also raises questions about the sustainability of contemporary infrastructure, which often prioritizes short-term cost over long-term durability.

For those studying or replicating historical infrastructure, the wooden pipeline’s operational duration provides a practical lesson in balancing material limitations with innovative design. While wood is susceptible to decay, its use in this context demonstrates how environmental factors (e.g., groundwater levels, soil acidity) and external treatments (e.g., pitch coating) can mitigate risks. Modern adaptations might explore hybrid systems combining wood with synthetic materials to enhance durability while retaining sustainability benefits. The pipeline’s 40-year run serves as a benchmark for evaluating the resilience of alternative materials in similar applications.

Finally, the pipeline’s decommissioning in the late 1890s reflects the inevitable shift toward more advanced materials and technologies. As cities grew and water demands increased, wooden pipelines could no longer meet capacity or hygiene standards. However, their operational duration remains a fascinating case study in resourcefulness and adaptability. For historians, engineers, and environmentalists, it offers a reminder that infrastructure lifespans are shaped not just by materials but by the socio-economic contexts in which they operate. The wooden pipeline’s legacy endures as a symbol of what can be achieved with limited resources and thoughtful design.

White Spirit Drying Time on Wood: Quick Guide for Woodworkers

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$16.99

Historical Significance: Impact and legacy of the pipeline in American history and engineering

America's longest wooden pipeline, stretching over 120 miles from the Hudson River to the Delaware and Hudson Canal, was a marvel of 19th-century engineering. Completed in 1828, it played a pivotal role in the industrial development of the northeastern United States. This pipeline, constructed entirely from wood, was a testament to the ingenuity and resourcefulness of early American engineers. Its primary purpose was to transport water, a critical resource for powering the burgeoning canal system, which in turn facilitated the movement of goods and raw materials across the region.

Analytically, the wooden pipeline’s historical significance lies in its role as a catalyst for economic growth. By ensuring a reliable water supply, it enabled the expansion of the canal network, which was the lifebeline of pre-railroad commerce. This infrastructure supported industries such as coal mining, timber, and agriculture, fostering regional trade and urbanization. The pipeline’s success demonstrated the feasibility of large-scale water management projects, setting a precedent for future engineering endeavors. Its impact extended beyond immediate economic benefits, shaping the landscape of American industrialization and infrastructure development.

Instructively, the construction of the wooden pipeline offers valuable lessons in material science and engineering adaptability. Engineers of the era utilized hemlock wood for its durability and resistance to decay, a choice informed by the available resources and technological constraints. The pipeline’s design, featuring interlocking wooden staves bound by iron hoops, showcased innovative problem-solving. Modern engineers can draw parallels to sustainable construction practices, emphasizing the importance of selecting materials suited to environmental conditions and project requirements. This historical example underscores the enduring relevance of resourcefulness in overcoming technical challenges.

Persuasively, the legacy of the wooden pipeline highlights the importance of preserving and studying historical engineering feats. While the pipeline itself no longer exists, its impact on American history and engineering is undeniable. Efforts to document and commemorate such projects ensure that future generations can learn from past achievements. By integrating these lessons into contemporary education and practice, we can inspire innovation and foster a deeper appreciation for the foundations of modern infrastructure. The wooden pipeline serves as a reminder that even seemingly obsolete technologies can offer profound insights into progress and perseverance.

Comparatively, the wooden pipeline’s role in American history can be juxtaposed with other transformative infrastructure projects, such as the Erie Canal and the Transcontinental Railroad. While each served distinct purposes, they collectively illustrate the nation’s commitment to connectivity and economic advancement. The pipeline’s uniqueness lies in its material composition and specific function, yet it shares a common legacy of shaping the American landscape. This comparison underscores the interconnectedness of historical engineering projects and their cumulative impact on societal development.

Descriptively, the wooden pipeline’s construction was a monumental undertaking, requiring thousands of wooden logs, meticulous craftsmanship, and arduous labor. Workers faced harsh conditions, navigating rugged terrain and seasonal challenges to complete the project. The pipeline’s route, snaking through forests and valleys, became a symbol of human determination and the quest for progress. Its presence transformed the region, leaving an indelible mark on both the physical and cultural landscape. Today, while the pipeline itself has faded into history, its story endures as a testament to the power of innovation and the enduring legacy of early American engineering.

Lexi Wood and Presley Gerber's Short-Lived Romance: A Timeline

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

America's longest wooden pipeline, known as the "Wooden Pipe Line," was approximately 120 miles long.

The longest wooden pipeline was located in Pennsylvania, primarily serving the oil fields in the Titusville and Pithole regions.

The wooden pipeline was constructed in the late 1860s during the Pennsylvania oil boom, with significant expansion occurring between 1865 and 1868.

The pipeline was used to transport crude oil from oil fields to refineries and railheads, revolutionizing the oil industry by reducing transportation costs and improving efficiency.

The wooden pipeline remained in operation for about a decade, until the late 1870s, when it was gradually replaced by more durable iron and steel pipelines.