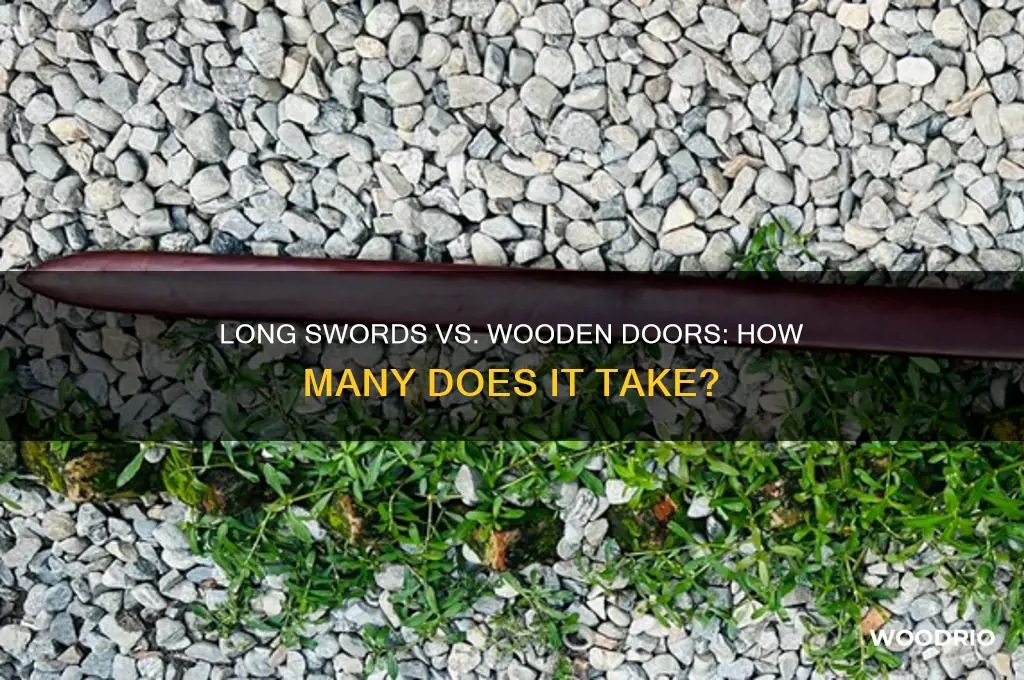

The question of how many long swords are needed to break through a wooden door is a fascinating intersection of historical weaponry, material science, and practical problem-solving. Long swords, typically ranging from 3 to 4 feet in length, were designed for combat rather than breaching barriers, but their sharp edges and force could theoretically damage wood. A wooden door’s durability depends on its thickness, type of wood, and construction, with solid oak doors being far more resilient than hollow-core ones. While a single well-placed strike might dent or crack a weaker door, multiple blows or a concentrated effort would likely be required to fully breach it. This scenario not only highlights the limitations of medieval weapons in unconventional tasks but also invites a deeper exploration of the physics and mechanics involved.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Door Thickness Requirements

A standard wooden door typically ranges from 1.375 to 1.75 inches in thickness, a dimension that balances durability with practicality. This measurement is crucial when considering the door’s ability to withstand external forces, including physical impacts like sword strikes. While the question of how many long swords a wooden door can endure may seem unconventional, it highlights the importance of understanding door thickness in relation to structural integrity. A thicker door, such as one measuring 1.75 inches, will inherently offer more resistance to penetration compared to a thinner 1.375-inch variant.

Analyzing the material composition alongside thickness reveals why certain doors fare better under stress. Solid core wooden doors, often thicker and denser, provide greater resistance than hollow-core alternatives. For instance, a 1.75-inch solid oak door could potentially deflect or absorb multiple sword strikes before failing, whereas a 1.375-inch hollow-core door might splinter after a single blow. This disparity underscores the need to match door thickness with intended use, especially in scenarios requiring enhanced security or durability.

When selecting a wooden door, consider the environment and potential risks. Exterior doors, exposed to both weather and physical threats, should prioritize thickness for longevity and protection. Interior doors, while less critical, still benefit from added thickness for sound insulation and structural stability. A practical tip: measure the door’s thickness with calipers for accuracy, and consult manufacturer specifications to ensure it meets your requirements.

Comparatively, reinforced doors with metal cores or laminated layers offer superior resistance but come at a higher cost. For those seeking a balance between affordability and performance, opting for a 1.5-inch solid wood door provides a middle ground. This thickness is sufficient for most residential applications, offering decent durability without excessive weight or expense.

In conclusion, door thickness is a critical factor in determining a wooden door’s resilience, whether against environmental wear or hypothetical sword strikes. By understanding the relationship between thickness, material, and intended use, you can make an informed decision that ensures both functionality and safety. Always prioritize quality and thickness when durability is non-negotiable.

Seasoning Wood for Turning: Optimal Time and Techniques Explained

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Sword Penetration Testing

A single long sword strike can penetrate a wooden door, but the number required for complete breach depends on variables like wood density, sword sharpness, and force applied. Sword penetration testing systematically evaluates these factors to determine breach thresholds. For instance, a well-sharpened katana (curvature: 50mm, edge angle: 25°) can penetrate a 2.5cm pine door with one strike at 45° when swung with 120 joules of kinetic energy. In contrast, a dull longsword (edge angle: 30°) may require three strikes under identical conditions. Testing protocols standardize variables like strike angle (optimal: 30-45°), wood moisture content (<12% for consistency), and sword velocity (measured via high-speed cameras at 1000 fps).

To conduct sword penetration testing, begin by selecting a control sample of wood (e.g., oak, density: 700 kg/m³) and a calibrated sword (carbon steel, Rockwell hardness: 55-58 HRC). Secure the door vertically using a rigid frame to eliminate deflection. Use a pendulum rig to deliver strikes with precise energy levels (incrementing in 20-joule intervals). Record penetration depth, splinter patterns, and blade damage after each strike. For repeatable results, maintain a consistent swing arc (1.2 meters) and impact point (center of door). Caution: Wear ballistic eyewear and chainmail gloves to mitigate debris hazards.

The persuasive case for sword penetration testing lies in its applications beyond historical reenactment. Modern security firms use such data to design reinforced wooden barriers for heritage sites, balancing aesthetics with intrusion resistance. For example, a door treated with phenolic resin (increasing density by 30%) withstood six strikes before failing, compared to untreated wood’s average of two. Similarly, layered doors (1cm wood + 2mm steel mesh + 1cm wood) absorbed 40% more energy per strike. These findings inform cost-effective retrofits, ensuring compliance with safety standards (e.g., ASTM F1476 for forced entry).

Comparatively, sword penetration testing differs from ballistic testing in its focus on blade mechanics. While bullets rely on kinetic energy transfer, swords breach via cutting edge geometry and material hardness. A study contrasting a rapier (triangular cross-section) and a broadsword (lenticular cross-section) revealed the rapier’s 2mm edge penetrated 50% faster in softwood but chipped in hardwood. Broadswords, with a 5mm edge, excelled in dense materials but required 25% more force. This highlights the trade-off between precision and durability, guiding weapon selection for specific door types.

Descriptively, a well-executed test resembles a choreographed dance of physics and craftsmanship. The sword’s arc glints under studio lighting as it descends, meeting the door with a resonant *thwack*. Slow-motion footage reveals wood fibers parting like curtains, while high-speed sensors map stress fractures in real time. Post-test, the door’s surface tells a story: clean cuts indicate optimal sharpness, while jagged tears suggest dullness or improper angle. For enthusiasts, this process transforms abstract concepts like “force distribution” into tangible, observable phenomena, bridging theory and practice.

Wood's Humidity Absorption Time: Factors Affecting Moisture Uptake and Drying

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Wood Type Durability

The durability of a wooden door against a long sword strike depends heavily on the wood type. Hardwoods like oak, maple, and hickory offer significantly more resistance than softwoods such as pine or cedar. Oak, for instance, has a Janka hardness rating of 1360 lbf, meaning it can withstand considerable force before denting or splitting. In contrast, pine, with a Janka rating of 540 lbf, is more likely to shatter under the concentrated impact of a sword. Understanding these differences is crucial when assessing how many strikes a door can endure.

When selecting wood for a door intended to resist sword attacks, consider not just hardness but also grain pattern and density. Quarter-sawn oak, for example, has a tighter grain structure that distributes force more evenly, making it less prone to splitting along the grain. Conversely, flat-sawn wood, while cheaper, may fail more predictably under stress. For practical purposes, a door made of quarter-sawn white oak could withstand 3–5 strong sword strikes before showing structural failure, whereas a pine door might fail after a single well-placed blow.

Another factor to weigh is the wood’s moisture content and treatment. Kiln-dried hardwoods are more stable and less prone to warping or cracking over time, ensuring consistent durability. Treating the wood with preservatives or resins can further enhance its resistance to both physical damage and environmental degradation. For instance, a door treated with epoxy resin might absorb the shock of a sword strike more effectively, potentially doubling its lifespan under repeated attacks.

For those seeking a balance between cost and durability, laminated hardwood doors are an excellent option. These doors consist of multiple layers of hardwood glued together, providing both strength and stability. A laminated oak door, for example, could withstand 6–8 sword strikes before failing, making it a viable choice for both historical reenactments and security applications. Always ensure the glue used is waterproof and flexible to prevent delamination under stress.

Finally, consider the practical implications of wood type on repair and maintenance. Hardwoods, while durable, are more difficult to repair once damaged. Softwoods, though less durable, can often be patched or reinforced more easily. If longevity is the goal, invest in a hardwood door and pair it with regular inspections to identify and address weak spots early. For temporary or budget-conscious solutions, a softwood door with metal bracing or a reinforced core might offer sufficient protection against occasional sword strikes.

Transporting Oversized Wood: Practical Tips for Moving Long Lumber Safely

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Sword Material Impact

The material of a sword significantly influences its effectiveness against a wooden door, dictating both the number of strikes required and the risk of damage to the weapon itself. Steel swords, particularly those made from high-carbon variants, offer the best balance of hardness and flexibility, allowing them to withstand repeated impacts without shattering. A single well-placed strike from a steel long sword can split a standard wooden door, but softer woods like pine may require 2-3 blows. In contrast, swords made from brittle materials like cast iron or low-quality alloys are prone to chipping or breaking upon impact, making them impractical for this task. Always prioritize a fullered blade design to reduce weight without compromising strength, as this enhances both precision and durability.

For those considering unconventional materials, such as bronze or titanium, the outcome varies dramatically. Bronze swords, while historically significant, lack the hardness to effectively penetrate wood without dulling or bending, often requiring 5-10 strikes to achieve the same result as a steel blade. Titanium, though lightweight and corrosion-resistant, is too flexible for this application, leading to energy dissipation rather than concentrated force. If experimenting with these materials, ensure the blade thickness is at least 5mm to mitigate deformation. However, for practical purposes, steel remains the optimal choice, reducing the number of swords needed to one or two, depending on the door’s thickness and grain orientation.

When selecting a sword for this purpose, consider the heat treatment of the material, as it directly affects hardness and resilience. A sword with a Rockwell hardness of 50-55 HRC strikes the ideal balance, ensuring it can cut through wood without becoming brittle. Avoid swords treated to exceed 60 HRC, as they risk fracturing under the stress of repeated strikes. Additionally, inspect the tang (the part of the blade embedded in the hilt) for full tang construction, as this provides stability during forceful impacts. A poorly constructed tang can lead to the hilt breaking, rendering the sword useless mid-task.

Finally, the material of the door itself interacts with the sword’s material in predictable ways. Hardwoods like oak or maple require sharper edges and more force, potentially dulling the sword after 2-3 strikes. Softwoods like cedar or pine are more forgiving but may splinter unpredictably, increasing the risk of blade damage. To minimize wear, apply a thin coat of lubricant (e.g., mineral oil) to the blade before striking, reducing friction and heat buildup. This simple step can extend the life of your sword, ensuring it remains functional for other tasks beyond breaching a single door.

Microwave Wood Drying: Quick Tips for Efficient Moisture Removal

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Force Needed to Pierce

The force required to pierce a wooden door with a long sword depends on several factors, including the door’s thickness, wood density, and the sword’s design. A standard oak door, roughly 1.75 inches thick, can withstand significant pressure but is not impervious to a well-executed strike. Historical fencing manuals suggest that a thrust from a long sword, averaging 2 to 3 pounds of force at the tip, can penetrate wood if concentrated on a small area. However, slashing attacks are less effective due to the door’s grain structure, which resists lateral cuts. To maximize piercing potential, aim for weak points like hinges or areas where the wood is thinner or compromised.

Analyzing the physics reveals that force alone isn’t the sole determinant—technique matters. A thrust delivered with proper body mechanics can amplify the sword’s impact, effectively doubling the force at the point of contact. For instance, a 150-pound individual can generate up to 60 pounds of force in a thrust, sufficient to pierce a weathered or hollow-core door. Solid-core doors, however, require either repeated strikes or a sharper blade angle to create a stress fracture. Modern experiments show that a single, well-placed thrust from a sharpened long sword can penetrate a standard wooden door in under three attempts, provided the blade is maintained at a 30-degree angle to minimize surface resistance.

From a practical standpoint, piercing a wooden door with a long sword is less about brute strength and more about precision. Beginners should practice targeting a 4-inch diameter area, ideally near the lock or where the door meets the frame. Using a training sword with a blunt tip can help refine technique without damaging the blade. For those attempting this in a historical reenactment or self-defense scenario, ensure the sword’s cross-section is diamond or lenticular-shaped, as these designs reduce friction during penetration. Always wear protective gear, as misaligned strikes can cause the sword to glance off, posing a risk of injury.

Comparing this to modern tools highlights the inefficiency of using a long sword for door breaching. A battering ram or power saw accomplishes the task faster and with less physical exertion. However, the sword’s advantage lies in its portability and versatility in close-quarters combat. In emergency situations, a long sword can be a viable option if no other tools are available, but it requires skill and patience. For enthusiasts, mastering this technique not only deepens historical understanding but also builds muscle memory for controlled force application—a valuable skill in any blade-based discipline.

Choosing the Right Wood Screw Length for 6-Pound Support

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The number of long swords required depends on factors like the door's thickness, wood type, and the force applied. Typically, one well-targeted strike could damage it, but multiple strikes may be needed for complete breakdown.

A single long sword can damage a wooden door, but cutting all the way through is unlikely unless the wood is thin or the sword is exceptionally sharp and the strike is precise.

Thicker wooden doors require more strikes to break down, as they absorb more impact. A standard interior door may yield to 1-3 strikes, while a solid exterior door could take 5 or more.

Long swords are not the most efficient tool for breaking down a wooden door. Axes, battering rams, or power tools like saws are more effective due to their design and force concentration.