Long before the advent of modern adhesives and power tools, ancient craftsmen employed ingenious techniques to join long wood boards, ensuring structural integrity and durability. One of the earliest methods involved the use of wooden pegs or dowels, which were inserted into pre-drilled holes in the boards, creating a strong mechanical bond. Another traditional approach was the tongue-and-groove joint, where one board featured a protruding ridge (tongue) that fit snugly into a corresponding groove on the adjacent board, allowing for seamless alignment and stability. Additionally, mortise-and-tenon joints, which involved carving a hole (mortise) in one piece and a matching projection (tenon) on the other, were widely used for their strength and precision. These time-honored techniques not only showcased the skill and ingenuity of early woodworkers but also laid the foundation for many modern woodworking practices.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Methods Used | Mortise and Tenon, Dovetail Joints, Tongue and Groove, Scarf Joints, Splines, Pegged Joints, Gluing, Nailing (with hand-forged nails) |

| Tools Required | Chisels, saws, mallets, planes, augers, braces, hand drills |

| Materials | Wood (hardwoods like oak, maple, or pine), animal glue, wooden pegs, hand-forged nails |

| Strength | High, especially with interlocking joints like mortise and tenon or dovetail |

| Durability | Long-lasting, with many ancient examples still intact |

| Aesthetic | Often decorative, with visible joinery adding to the craftsmanship |

| Skill Level Required | High, as precise handwork and fitting were essential |

| Time Consumption | Labor-intensive, requiring significant time for cutting and fitting |

| Common Applications | Furniture, shipbuilding, timber framing, flooring, and cabinetry |

| Historical Period | Used extensively in ancient Egypt, Greece, Rome, and medieval Europe |

| Modern Relevance | Still used in traditional woodworking and restoration projects |

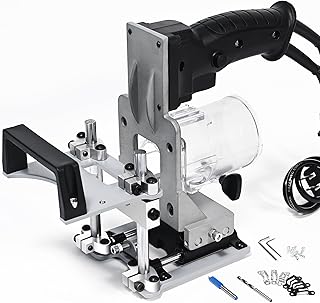

Explore related products

$34.07 $49.99

What You'll Learn

- Mortise and Tenon Joinery: Ancient technique using a hole and peg for strong, durable wood connections

- Dovetail Joints: Interlocking triangular shapes for precise, long-lasting corner joints in woodworking

- Tongue and Groove: Fitting boards with a ridge and slot for seamless, aligned connections

- Pegged Joints: Wooden dowels securing joints, common in traditional furniture and timber framing

- Spline Joinery: Thin strips inserted into grooves to strengthen and align miter or butt joints

Mortise and Tenon Joinery: Ancient technique using a hole and peg for strong, durable wood connections

Long before metal fasteners dominated woodworking, mortise and tenon joinery provided a simple yet ingenious solution for connecting long wood boards. This ancient technique, dating back to at least 7,000 BCE, relies on a precise fit between a projecting piece (the tenon) and a corresponding hole (the mortise), often secured with a peg for added strength. Its enduring popularity across cultures—from Egyptian furniture to medieval European timber framing—underscores its reliability and adaptability.

Crafting the Joint: Precision Meets Patience

To create a mortise and tenon joint, begin by marking the tenon’s width on the end of one board, ensuring it matches the mortise’s dimensions. Use a sharp chisel to carefully remove material, creating a snug fit. For the mortise, measure and mark the hole’s location on the receiving board, then drill or chisel out the cavity. A dry fit is essential to test alignment before final assembly. Pro tip: Use a peg hole slightly smaller than the peg itself, moistening the peg to allow for expansion as it dries, creating a tighter bond.

Strength in Simplicity: Why It Endures

The mortise and tenon joint’s strength lies in its mechanical interlock, distributing stress along the grain of the wood rather than relying on glue or fasteners alone. This makes it ideal for load-bearing structures like doors, tables, and even ships. Unlike dovetail joints, which excel in cabinetry, mortise and tenon joints handle shear forces better, making them versatile for both decorative and structural applications. Historical examples, such as the timber-framed buildings of medieval Europe, still stand today, a testament to the joint’s durability.

Modern Adaptations: Blending Old and New

While traditional hand tools like chisels and mallets remain effective, modern woodworkers often use power tools such as routers and drill presses to expedite the process. For added stability, consider reinforcing the joint with waterproof glue or epoxy, especially in outdoor applications. However, purists argue that a well-fitted mortise and tenon joint, secured with a hardwood peg, requires no additional adhesives. Experiment with different wood species—hardwoods like oak or maple provide superior strength, while softer woods like pine are easier to work with for beginners.

Practical Tips for Success

Accuracy is paramount; even a millimeter’s deviation can compromise the joint’s integrity. Use a marking gauge to ensure consistent lines, and clamp the workpieces securely during cutting and assembly. For larger projects, such as timber framing, pre-drilling peg holes prevents splitting. Finally, sand the tenon lightly to ease insertion without sacrificing the tight fit. With practice, this ancient technique becomes second nature, offering a timeless way to join wood with elegance and strength.

Perfectly Crispy Chicken of the Woods: Frying Time Guide

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Dovetail Joints: Interlocking triangular shapes for precise, long-lasting corner joints in woodworking

Long before modern adhesives and power tools, woodworkers relied on ingenious joinery techniques to create durable and aesthetically pleasing structures. Among these, the dovetail joint stands out as a testament to craftsmanship and precision. Characterized by interlocking triangular shapes, dovetail joints are renowned for their strength and longevity, particularly in corner joints where stability is critical. This technique, which dates back to ancient civilizations, remains a cornerstone in fine woodworking today.

To create a dovetail joint, the ends of two boards are carved with a series of trapezoidal pins and tails that fit together like a puzzle. The process begins with marking out the joint layout, typically using a marking gauge or template. The woodworker then carefully cuts the tails on one board, ensuring each angle is precise. Next, the pins are transferred to the adjoining board by fitting it against the tails and marking the corresponding shapes. Once cut, the pins and tails interlock tightly, forming a joint that resists pulling apart. For added durability, a small amount of glue can be applied, though the mechanical strength of the dovetail often eliminates the need for adhesives.

One of the most compelling aspects of dovetail joints is their ability to withstand the test of time. Unlike butt joints or simple miters, dovetails distribute stress evenly across the joint, reducing the likelihood of failure under pressure or movement. This makes them ideal for applications like drawers, boxes, and furniture frames, where structural integrity is paramount. Additionally, the exposed dovetail joint is often left visible as a decorative element, showcasing the artisan’s skill and adding a touch of elegance to the piece.

While mastering dovetail joinery requires practice and patience, the investment pays off in both functionality and beauty. Beginners can start with hand tools like a dovetail saw and chisels, gradually refining their technique before moving to more advanced tools like a router or dovetail jig. A practical tip for novices is to use softer woods like pine for practice, as they are more forgiving than hardwoods. For those seeking precision, marking out the joint with a 1:6 or 1:8 slope ensures a tight fit without excessive strain on the wood fibers.

In comparison to other traditional joinery methods, such as mortise and tenon or box joints, dovetail joints offer a unique blend of strength and visual appeal. While mortise and tenon joints excel in load-bearing applications, dovetails are unmatched in corner joints where resistance to tension and racking forces is essential. Box joints, though simpler to execute, lack the interlocking depth of dovetails, making them less durable in high-stress scenarios. Ultimately, the dovetail joint remains a timeless technique that bridges the gap between form and function, proving that sometimes, the oldest methods are still the best.

The Belskies' Survival: Uncovering Their Time in the Woods

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$102.79 $149.99

Tongue and Groove: Fitting boards with a ridge and slot for seamless, aligned connections

Long before modern adhesives and power tools, woodworkers relied on ingenious joinery techniques to connect long boards seamlessly. Among these, the tongue and groove method stands out for its simplicity and effectiveness. This technique involves creating a protruding ridge (the tongue) on one edge of a board and a corresponding slot (the groove) on the adjacent edge of another board. When fitted together, these elements interlock, forming a tight, aligned joint that requires no additional fasteners for stability.

Steps to Create a Tongue and Groove Joint:

- Prepare the Boards: Ensure the wood is straight and free of defects. Measure and mark the edges where the tongue and groove will be cut.

- Cut the Tongue: Use a table saw or router with a tongue-cutting bit to create a centered ridge along one edge of the board. The tongue should be slightly narrower than the groove to allow for expansion and contraction.

- Cut the Groove: On the adjacent board, cut a matching slot using a groove-cutting bit or a dado blade. The groove should be deep enough to accommodate the tongue snugly but not so tight as to cause splitting.

- Test the Fit: Dry-fit the boards to ensure the tongue slides smoothly into the groove. Sand or adjust the cuts as needed for a perfect fit.

- Assemble the Joint: Apply a thin layer of wood glue along the tongue and groove to enhance strength and stability. Press the boards together firmly, wiping away excess glue immediately.

Cautions and Practical Tips:

- Always use sharp tools to achieve clean, precise cuts. Dull blades can tear the wood grain, weakening the joint.

- For flooring or paneling, leave a small gap (1/16 inch) between boards to allow for wood movement due to humidity changes.

- When joining boards end-to-end, stagger the seams to distribute stress evenly and improve visual appeal.

Comparative Advantage:

Unlike butt joints, which rely on fasteners and often leave visible gaps, tongue and groove joints provide a flush, seamless connection. Compared to dovetail or box joints, tongue and groove is quicker to execute and requires less material removal, making it ideal for long runs of flooring, wainscoting, or ceiling panels. Its versatility and strength have ensured its enduring popularity in both traditional and modern woodworking.

Takeaway:

The tongue and groove joint exemplifies the elegance of traditional joinery, combining functionality with aesthetic appeal. By mastering this technique, woodworkers can achieve durable, aligned connections that enhance the structural integrity and visual harmony of their projects. Whether restoring antique furniture or installing contemporary flooring, this timeless method remains a cornerstone of woodworking craftsmanship.

Efficient Wood Fence Installation: Timeframe and Tips for Success

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Pegged Joints: Wooden dowels securing joints, common in traditional furniture and timber framing

Long before metal fasteners dominated woodworking, pegged joints emerged as a simple yet effective method for joining long wood boards. This technique, which relies on wooden dowels to secure joints, was a cornerstone of traditional furniture making and timber framing. Its enduring appeal lies in its strength, simplicity, and the seamless aesthetic it provides, allowing woodworkers to create durable structures without visible hardware.

To create a pegged joint, begin by drilling matching holes in the wood pieces to be joined. The diameter of the dowel should be proportional to the thickness of the wood, typically ranging from ¼ inch to ½ inch. For optimal strength, ensure the holes are straight and align precisely. A dowel slightly longer than the combined depth of the holes allows for a snug fit, with the excess trimmed flush after assembly. This method is particularly effective in mortise-and-tenon or bridle joints, where the dowel acts as a mechanical fastener, preventing shifting or separation over time.

One of the key advantages of pegged joints is their adaptability to various woodworking projects. In timber framing, for instance, pegs were used to secure massive beams, ensuring structural integrity without compromising the natural beauty of the wood. Similarly, in furniture making, pegged joints provided a clean, unobtrusive way to join legs, rails, and panels. The use of hardwood dowels, such as oak or maple, enhances durability, as these species resist splitting and wear better than softer woods.

Despite their historical prevalence, pegged joints remain a practical choice for modern woodworkers. They require minimal tools—a drill, dowels, and a saw—making them accessible for both professionals and hobbyists. However, precision is critical; misaligned holes or improperly sized dowels can weaken the joint. For best results, use a doweling jig to guide drilling and select dowels with a moisture content matching the surrounding wood to prevent warping.

In conclusion, pegged joints exemplify the ingenuity of traditional woodworking, combining functionality with elegance. By mastering this technique, woodworkers can honor centuries-old craftsmanship while creating pieces that stand the test of time. Whether restoring antique furniture or building new structures, pegged joints offer a timeless solution for joining long wood boards securely and beautifully.

Wood Pigeon Parenting: Duration of Feeding Their Young Explained

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$100.19

Spline Joinery: Thin strips inserted into grooves to strengthen and align miter or butt joints

Spline joinery, a technique where thin strips of wood are inserted into grooves to reinforce and align joints, has been a cornerstone of woodworking for centuries. This method, particularly effective for miter and butt joints, addresses the inherent weaknesses of these connections by distributing stress and ensuring precise alignment. Historically, splines were often made from hardwoods like oak or walnut, chosen for their strength and durability. The simplicity of the technique—cutting matching grooves in the boards and inserting a spline—made it accessible to craftsmen with limited tools, ensuring its widespread adoption across cultures and eras.

To execute spline joinery effectively, begin by marking the joint line on both boards. Use a table saw or router to cut identical grooves along the joint, ensuring they are deep enough to accommodate the spline but not so deep as to weaken the wood. The spline itself should be slightly thicker than the groove to create a snug fit. For miter joints, align the boards at a 45-degree angle, while butt joints require a straight edge. Insert wood glue into the grooves before sliding the spline into place, clamping the joint until the glue dries. This process not only strengthens the joint but also hides imperfections in alignment, making it both functional and aesthetically pleasing.

One of the most compelling aspects of spline joinery is its versatility. While traditionally used in furniture making, it has found modern applications in cabinetry, flooring, and even large-scale construction. For instance, splines are often employed in the assembly of wooden doors, where they provide stability to the mitered corners. In flooring, splines can be used to join long planks, reducing the risk of warping or separation over time. The technique’s adaptability is further enhanced by the variety of materials available for splines today, including metal and plastic, though wood remains the most authentic and historically accurate choice.

Despite its effectiveness, spline joinery is not without its challenges. Achieving precise alignment requires careful measurement and cutting, as even minor discrepancies can compromise the joint’s integrity. Additionally, the visibility of the spline can be a double-edged sword—while it can add a decorative element, it may also detract from the overall design if not executed thoughtfully. To mitigate this, craftsmen often select spline materials that complement the main wood or use contrasting colors to create intentional visual interest. Practice and patience are key to mastering this technique, but the results—strong, seamless joints—are well worth the effort.

In conclusion, spline joinery stands as a testament to the ingenuity of ancient woodworking practices, offering a simple yet effective solution to the challenges of joining long boards. Its enduring relevance in both traditional and modern applications underscores its value as a technique worth preserving and refining. Whether you’re a seasoned woodworker or a novice, incorporating spline joinery into your projects can elevate both their strength and beauty, bridging the gap between historical craftsmanship and contemporary design.

Mesquite Wood Seasoning Time: A Comprehensive Guide to Perfectly Dried Logs

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Ancient woodworkers used techniques like mortise and tenon joints, dovetail joints, and wooden pegs (dowels) to join long boards securely without metal fasteners.

Traditional tools included chisels, saws, augers (for drilling holes), and mallets. These hand tools allowed for precise cutting and fitting of joints.

Yes, natural adhesives like animal hide glue, plant resins, and even egg whites were used in some cultures to strengthen wood joints.

Viking shipbuilders used overlapping planks with iron rivets and wooden pegs, along with a technique called "clinker building," where planks were joined edge-to-edge for strength and flexibility.

Japanese woodworkers relied heavily on intricate joinery techniques like the "kanawatsu" (double-tenon joint) and "tsugi" (splice joint), often without using nails or glue, emphasizing precision and craftsmanship.