The long wooden bar found in old fortresses, often referred to as a battering ram or ram, was a crucial siege weapon used in ancient and medieval warfare. Typically constructed from sturdy wood and reinforced with metal, this heavy tool was designed to breach fortified walls, gates, or doors by repeatedly striking them with immense force. Operated by a team of soldiers who would swing it back and forth using ropes or handles, the ram’s effectiveness lay in its ability to concentrate significant kinetic energy on a small area, eventually weakening and breaking through defensive structures. Its presence in historical sieges highlights the ingenuity and brutality of pre-modern military engineering.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Purpose of the Bar: Defensive tool to block gates, prevent enemy entry, and control access during sieges

- Material and Design: Crafted from sturdy oak, often reinforced with iron, ensuring durability against attacks

- Historical Usage: Commonly used in medieval fortresses across Europe, Asia, and the Middle East

- Mechanism: Operated by sliding or lifting, secured in place by grooves or brackets for stability

- Modern Replicas: Found in restored castles, museums, and historical reenactments for educational purposes

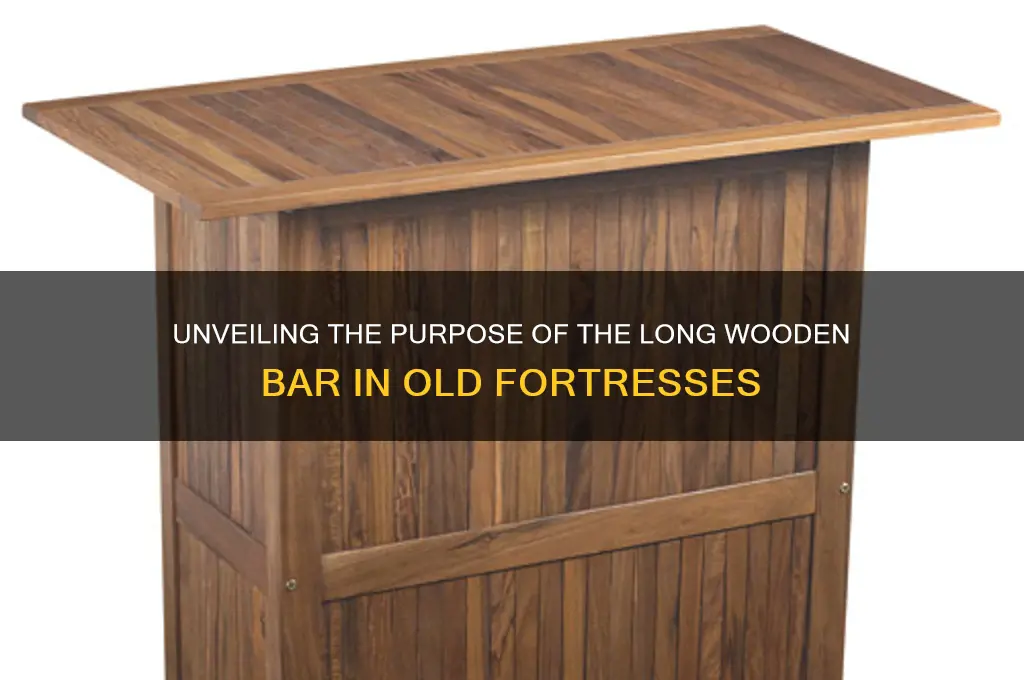

Purpose of the Bar: Defensive tool to block gates, prevent enemy entry, and control access during sieges

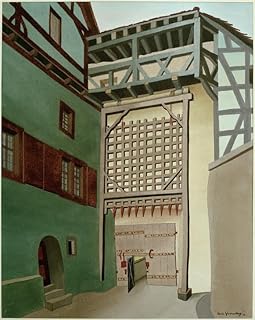

A simple yet ingenious device, the long wooden bar, often referred to as a "gate bar" or "beam," played a critical role in the defense of ancient fortresses. Its primary purpose was to act as a formidable barrier, securing the most vulnerable entry points – the gates. During sieges, when enemy forces sought to breach the fortress walls, this unassuming piece of timber became a crucial defensive tool.

The Mechanics of Defense: Imagine a massive wooden gate, its iron-clad surface designed to withstand battering rams. Now, picture a sturdy beam, carefully crafted to fit snugly into pre-cut grooves on either side of the gate. When threatened by an advancing army, defenders would swiftly maneuver this bar into place, effectively transforming the gate into an impenetrable wall. The bar's length and thickness were strategically calculated to distribute the force of any impact, making it incredibly difficult for attackers to dislodge.

A Tactical Advantage: The beauty of this system lies in its simplicity and effectiveness. By employing these bars, defenders could control access to the fortress with precision. In times of peace, the bars could be removed, allowing for the smooth flow of trade and communication. However, when under siege, the bars became a powerful tool for denial, forcing attackers to resort to more time-consuming and dangerous methods like scaling walls or digging tunnels. This delay provided defenders with a crucial advantage, allowing them to prepare, reinforce, and potentially outlast the besieging forces.

Historical Evidence and Evolution: Archaeological evidence and historical accounts from various civilizations, including the Romans, Greeks, and medieval Europeans, attest to the widespread use of gate bars. Over time, these bars evolved in design, incorporating metal reinforcements and complex locking mechanisms. Some fortresses even employed multiple bars, adding layers of protection. The effectiveness of this defensive strategy is evident in the numerous failed siege attempts throughout history, where attackers, despite their numerical superiority, were unable to breach well-barred gates.

Modern Relevance and Lessons: While the era of medieval sieges has passed, the principles behind the long wooden bar's design remain relevant. In modern security systems, we see similar concepts applied, such as reinforced barriers, bollards, and advanced locking mechanisms. The gate bar's legacy reminds us that sometimes, the most effective solutions are not the most complex, but those that leverage simplicity, strength, and strategic placement to counter potential threats. Understanding this ancient defensive tool offers valuable insights into the timeless principles of security and access control.

Solar Kiln Wood Drying: Optimal Time for Perfectly Seasoned Lumber

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Material and Design: Crafted from sturdy oak, often reinforced with iron, ensuring durability against attacks

The long wooden bar found in old fortresses, often referred to as a portcullis or a barricade beam, was a critical defensive element. Its material and design were meticulously chosen to withstand relentless attacks. Crafted from sturdy oak, this choice was no accident. Oak, known for its density and natural resistance to decay, provided a robust foundation. However, to further enhance its durability, iron reinforcements were often integrated. These reinforcements, strategically placed at stress points, ensured the bar could endure battering rams, siege weapons, and the test of time.

Analyzing the construction process reveals a blend of craftsmanship and engineering ingenuity. Oak logs were carefully selected for their straight grain and absence of knots, ensuring structural integrity. Iron bands or plates were then affixed using rivets or spikes, creating a composite material that combined the flexibility of wood with the strength of metal. This hybrid design was particularly effective against blunt force, as the wood absorbed impact while the iron prevented splintering or cracking. For fortress builders, this meant a barrier that could be swiftly lowered into place, sealing off entry points with minimal maintenance.

From a practical standpoint, maintaining such a structure required periodic inspections and treatments. Oak, though durable, was susceptible to rot if exposed to constant moisture. To mitigate this, the wood was often treated with linseed oil or tar, which acted as a water repellent. Iron components, meanwhile, needed regular coating with grease or paint to prevent rust. These maintenance routines were as crucial as the initial design, ensuring the bar remained functional during prolonged sieges. For modern enthusiasts or restoration projects, replicating these treatments using historically accurate materials can preserve both authenticity and longevity.

Comparing the oak-and-iron design to alternatives highlights its superiority in medieval contexts. Stone barriers, while stronger, were immovable and prone to cracking under repeated strikes. Metal grilles, though effective against smaller projectiles, were costly and required advanced metallurgy. The oak bar, reinforced with iron, struck a balance between affordability, durability, and practicality. Its design allowed for quick deployment via rope-and-pulley systems, making it a versatile tool for defenders. This combination of material and function underscores why it became a staple in fortress architecture.

In conclusion, the long wooden bar’s design was a testament to the ingenuity of medieval engineers. By pairing oak’s natural resilience with iron’s strength, they created a barrier that could withstand the rigors of warfare. For those studying or restoring such structures, understanding this design’s intricacies offers valuable insights into historical craftsmanship. Whether for academic research or practical reconstruction, the principles behind this material choice remain as relevant today as they were centuries ago.

Durability of Wooden Garden Furniture: Lifespan and Maintenance Tips

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Historical Usage: Commonly used in medieval fortresses across Europe, Asia, and the Middle East

The long wooden bar, often referred to as a "drawbridge" or "portcullis bar," was a critical component in the defense mechanisms of medieval fortresses. Its primary function was to control access to the fortress, serving as a movable barrier that could be raised or lowered to allow or deny entry. This simple yet effective design was universally adopted across Europe, Asia, and the Middle East, reflecting its practicality and strategic importance in warfare.

In Europe, the drawbridge was typically hinged on one end, allowing it to pivot upward when raised. This design was often coupled with a counterweight system, usually a heavy stone or metal weight, to facilitate smooth operation. For instance, in the castles of England and France, the drawbridge was a standard feature over moats, providing a formidable obstacle to invading forces. The process of raising or lowering the bridge required coordination and strength, often involving a team of soldiers or mechanisms like winches and chains.

In contrast, the Middle Eastern and Asian fortresses frequently employed a different variation known as the "portcullis." This was a vertically descending grille made of wood or metal, often reinforced with spikes or sharp edges. The portcullis was operated by a system of ropes and pulleys, allowing it to be dropped rapidly to block the entrance. This design was particularly effective in repelling siege engines and infantry assaults. For example, the citadels of the Crusader states and the fortresses of the Ottoman Empire utilized portcullises to great effect, combining them with other defensive features like murder holes and arrow slits.

The strategic placement of these wooden bars was crucial. They were often positioned at the most vulnerable points of the fortress, such as the main gate or the entrance to the inner keep. In some cases, multiple bars or gates were used in succession to create a series of defensive layers. This layered defense forced attackers to breach multiple barriers, significantly slowing their advance and exposing them to defensive fire from above.

Maintenance of these wooden structures was essential to ensure their effectiveness. Regular inspections and repairs were conducted to prevent rot, warping, or damage from siege weapons. In regions with harsh climates, additional measures such as waterproofing treatments or the use of more durable woods like oak were employed. The longevity of these structures is evident in the many well-preserved examples found today, such as the drawbridge at Château de Carcassonne in France or the portcullis at the Citadel of Aleppo in Syria.

In conclusion, the long wooden bar was a versatile and indispensable tool in medieval fortress defense. Its design and implementation varied across regions, reflecting the unique challenges and resources of each area. Understanding its historical usage provides valuable insights into the ingenuity and strategic thinking of medieval engineers and military leaders. Whether as a drawbridge or a portcullis, this simple yet effective mechanism played a pivotal role in shaping the outcomes of countless sieges and battles throughout history.

Wood Pigeon Lifespan in the UK: Facts and Insights Revealed

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Mechanism: Operated by sliding or lifting, secured in place by grooves or brackets for stability

The long wooden bar found in old fortresses, often referred to as a portcullis or battering beam, was a critical defensive mechanism. Its operation relied on simplicity and robustness: sliding or lifting it into place to block entry. This design was secured by grooves or brackets, ensuring stability under immense pressure, whether from attackers or the weight of the bar itself. Such mechanisms were engineered to withstand siege warfare, blending functionality with the architectural constraints of medieval fortifications.

To operate a sliding portcullis, defenders would use a system of ropes, pulleys, or counterweights to move the bar vertically within grooves carved into the fortress walls. These grooves were precisely aligned to guide the bar smoothly, preventing jamming or misalignment during rapid deployment. Lifting mechanisms, on the other hand, often involved brackets or latches that locked the bar into an elevated position, allowing controlled access during peacetime. Both methods required minimal manpower, a crucial advantage during prolonged sieges when resources were scarce.

A comparative analysis reveals the superiority of grooved systems over bracket-secured designs in terms of durability. Grooves provided continuous support along the entire length of the bar, distributing stress evenly and reducing wear over time. Brackets, while effective for lighter beams, were more prone to failure under repeated impact from siege engines like battering rams. Fortresses in regions prone to frequent attacks, such as the borders of medieval kingdoms, often favored grooved mechanisms for their reliability.

For those restoring or replicating such mechanisms today, precision is paramount. Grooves should be cut with a tolerance of no more than 2 millimeters to ensure smooth operation while preventing lateral movement. Brackets must be forged from high-tensile materials, such as wrought iron, and secured with bolts capable of withstanding forces exceeding 10,000 newtons. Regular maintenance, including lubrication of moving parts and inspection for cracks, is essential to preserve functionality and historical authenticity.

In conclusion, the sliding or lifting mechanisms of long wooden bars in old fortresses exemplify the ingenuity of medieval engineering. By understanding the interplay between grooves, brackets, and operational forces, modern enthusiasts and historians can both appreciate and recreate these vital defensive tools. Whether for educational displays or functional restorations, adhering to historical principles ensures these mechanisms remain as effective and awe-inspiring as they were centuries ago.

How Long Does Plastic Wood Take to Dry? A Complete Guide

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Modern Replicas: Found in restored castles, museums, and historical reenactments for educational purposes

The long wooden bar often seen in old fortresses, known as a portcullis or a drawbar, served as a critical defensive mechanism. Today, its modern replicas are meticulously crafted to educate and immerse audiences in historical contexts. Found in restored castles, museums, and historical reenactments, these replicas bridge the gap between past and present, offering tangible connections to medieval engineering and warfare. Their presence is not merely decorative but serves as a hands-on tool for learning, allowing visitors to understand the ingenuity and practicality of ancient fortifications.

In restored castles, modern replicas of these wooden bars are often installed to recreate the fortress’s original defensive systems. For instance, at Warwick Castle in England, a functioning portcullis replica demonstrates how such mechanisms were operated to repel invaders. These installations are accompanied by interpretive panels or guided tours that explain their historical significance, materials used, and methods of operation. For educators and historians, this approach provides a dynamic way to teach about medieval architecture and military strategy, making abstract concepts tangible for visitors of all ages.

Museums take a more analytical approach, using replicas to dissect the design and functionality of these wooden bars. At the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, for example, a scaled replica of a fortress drawbar is paired with interactive displays that allow visitors to experiment with counterweights and pulley systems. Such exhibits not only showcase the engineering principles behind these structures but also highlight the labor and resources required to construct them. This hands-on engagement fosters a deeper appreciation for the craftsmanship and innovation of past civilizations.

Historical reenactments bring these replicas to life in a dramatic, immersive setting. During events like the Battle of Hastings reenactment, participants operate full-scale portcullis replicas to simulate siege scenarios. These activities are not just for entertainment; they serve as living history lessons, demonstrating the tactical importance of such defenses in medieval warfare. Organizers often provide safety guidelines, such as ensuring all moving parts are securely counterbalanced and restricting operation to trained individuals, to prevent accidents while maintaining authenticity.

For those interested in creating or using these replicas for educational purposes, practical considerations are key. Replicas should be constructed from durable, period-appropriate materials like oak or ash, and their dimensions should adhere to historical records or archaeological findings. Incorporating interactive elements, such as movable parts or accompanying audio guides, can enhance their educational value. Additionally, ensuring accessibility for all visitors, including those with disabilities, is essential. For instance, providing tactile models or descriptive audio for visually impaired guests can make the experience inclusive and impactful.

In conclusion, modern replicas of the long wooden bars found in old fortresses are invaluable educational tools. Whether in restored castles, museums, or historical reenactments, they offer unique insights into medieval life and technology. By combining historical accuracy with interactive engagement, these replicas not only preserve the past but also inspire curiosity and understanding in present and future generations.

Bona's Impact: Enhancing Wood Durability and Longevity Explained

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The long wooden bar on old fortress walls is often called a "battering ram" or "ram," though in some contexts, it could refer to a "brattice" or "hoarding," which are wooden platforms or galleries used for defense.

The long wooden bar, if referring to a battering ram, was used as a siege weapon to break down gates or walls. If it’s a structural feature like a brattice, it served as a defensive platform for soldiers to observe and attack enemies.

The construction varied depending on its purpose. Battering rams were typically made from a large, heavy log with a metal head, while brattices or hoardings were built as wooden extensions supported by beams or brackets attached to the fortress walls.

Yes, battering rams were famously used in sieges like the Roman assaults on fortified cities. Brattices and hoardings can be seen in the designs of castles like the Tower of London and Château de Carcassonne, where they provided defensive advantages during medieval times.

![Etching Described and Simplified, by a Practical Engraver [C. Castle]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/51j2GyRertL._AC_UL320_.jpg)