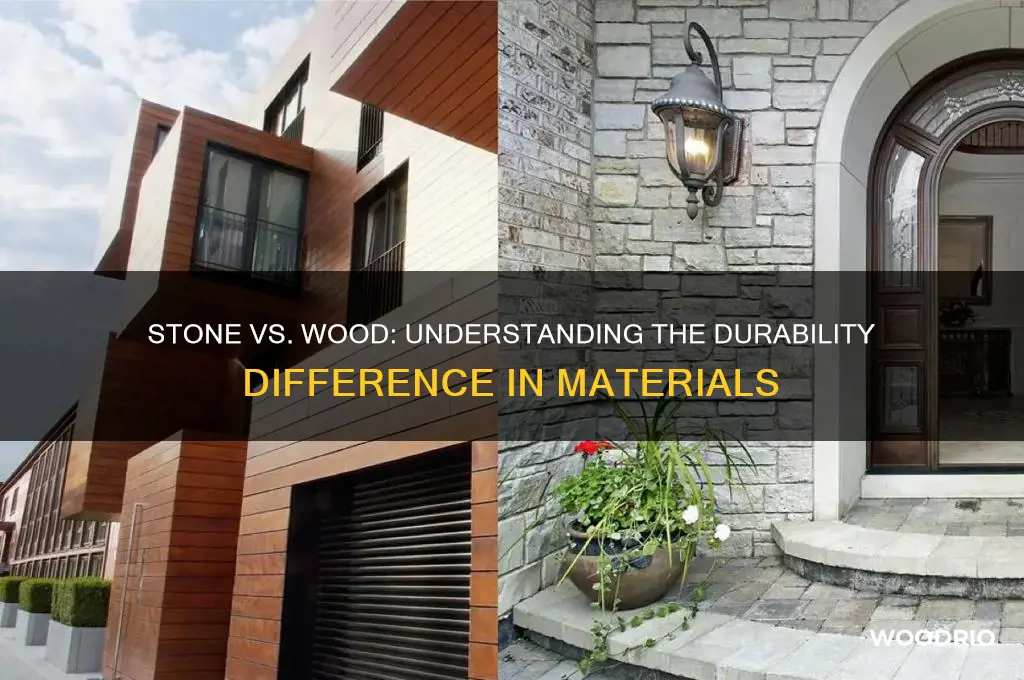

Stone lasts longer than wood primarily due to its inherent durability and resistance to environmental factors. Composed of minerals like quartz and feldspar, stone is naturally hard and less susceptible to decay, weathering, and biological degradation. Unlike wood, which is organic and prone to rot, insect damage, and moisture absorption, stone remains structurally stable over centuries. Its non-porous nature prevents water infiltration, reducing the risk of erosion and cracking, while its chemical composition resists corrosion and decomposition. Additionally, stone’s ability to withstand extreme temperatures and physical stress further contributes to its longevity, making it a superior material for construction and preservation compared to wood.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Density and Hardness | Stone is denser and harder than wood, making it more resistant to physical damage, wear, and abrasion. |

| Moisture Resistance | Stone is naturally waterproof and does not absorb moisture, preventing rot, warping, and decay. Wood, being hygroscopic, absorbs moisture, leading to structural degradation over time. |

| Biological Resistance | Stone is impervious to insects, fungi, and bacteria, which commonly infest and decompose wood. |

| Fire Resistance | Stone is non-combustible and does not burn, whereas wood is highly flammable and can be destroyed by fire. |

| Chemical Resistance | Stone is resistant to most acids, bases, and chemicals, while wood can be damaged by chemical reactions and corrosion. |

| Thermal Stability | Stone has low thermal expansion and contraction, maintaining its structure under temperature fluctuations. Wood expands and contracts significantly, leading to cracks and warping. |

| Durability Over Time | Stone can last for centuries or millennia with minimal maintenance, whereas wood typically degrades within decades, even with proper care. |

| Weathering Resistance | Stone withstands harsh weather conditions (e.g., rain, wind, UV radiation) better than wood, which can crack, splinter, or fade. |

| Maintenance Requirements | Stone requires little to no maintenance, while wood needs regular treatments (e.g., staining, sealing) to prolong its lifespan. |

| Environmental Impact | Stone is a non-renewable resource but lasts longer, reducing replacement needs. Wood is renewable but requires frequent replacement, increasing resource consumption. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Density and Porosity: Stone’s dense structure resists decay better than wood’s porous, absorbent nature

- Resistance to Rot: Stone doesn’t decompose; wood is vulnerable to fungi and bacteria

- Weathering Tolerance: Stone withstands extreme weather; wood warps, cracks, or erodes faster

- Chemical Stability: Stone resists chemical reactions; wood breaks down under acids or moisture

- Biological Immunity: Stone is impervious to pests; wood is prone to insect damage

Density and Porosity: Stone’s dense structure resists decay better than wood’s porous, absorbent nature

Stone's longevity over wood begins with its atomic structure. Unlike wood, which is a natural composite of cellulose and lignin, stone is a tightly packed arrangement of minerals like quartz, feldspar, and mica. This dense matrix leaves little room for water, air, or microorganisms to penetrate, creating a formidable barrier against decay. Imagine a fortress with walls so thick that invaders can't breach them—stone's density is its fortress.

Consider the porosity of wood, a characteristic that makes it susceptible to moisture absorption. When wood absorbs water, it swells, leading to warping, cracking, and eventually, rot. Fungi and bacteria thrive in this damp environment, accelerating decomposition. In contrast, stone's low porosity acts as a shield, repelling water and denying entry to these destructive organisms. For instance, a wooden fence post may last 10-15 years, while a stone pillar can stand for centuries, as seen in ancient Roman structures.

To illustrate the impact of density and porosity, let's examine a practical scenario. In coastal regions, where humidity and salt spray are prevalent, wooden structures deteriorate rapidly due to constant moisture exposure. Stone, however, remains largely unaffected. Its dense structure prevents salt crystals from forming within, avoiding the internal pressure that causes wood to crack. This is why lighthouses, often built with stone, endure the harsh marine environment for generations.

The key takeaway is that stone's density and low porosity are not just inherent properties but active defenders against decay. When selecting materials for long-lasting structures, especially in challenging environments, prioritize stone over wood. For outdoor projects, opt for dense stones like granite or quartzite, which have a porosity of less than 1%, compared to wood's 30-50%. Treat wood with sealants to reduce moisture absorption, but remember, this is a temporary solution. For true endurance, stone's natural resistance is unparalleled.

In essence, the battle between stone and wood is a contest of structure. Stone's dense, non-porous nature repels the very forces that dismantle wood. By understanding this fundamental difference, we can make informed choices, ensuring our creations withstand the test of time. Whether building a monument or a garden path, the lesson is clear: density and porosity are the silent guardians of stone's longevity.

Full Sun Wood Stain Drying Time: A Comprehensive Guide

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Resistance to Rot: Stone doesn’t decompose; wood is vulnerable to fungi and bacteria

Stone's enduring presence in ancient structures, from the pyramids to Roman aqueducts, highlights its remarkable resistance to decay. Unlike wood, stone is inorganic, lacking the organic compounds that fungi and bacteria feast on. These microorganisms, the primary culprits behind wood rot, find stone an inhospitable environment. Without the nutrients they need to thrive, they cannot break down stone's dense, mineral-based structure. This fundamental difference in composition explains why stone structures can stand for millennia while wooden ones, even when treated, eventually succumb to the forces of decomposition.

Wood, a natural wonder in its own right, is inherently vulnerable to the relentless attack of fungi and bacteria. These microscopic organisms secrete enzymes that break down the cellulose and lignin, the building blocks of wood, into simpler substances they can absorb. Moisture, warmth, and oxygen create the perfect breeding ground for these decomposers, accelerating the rotting process. While treatments like pressure-treating with chemicals can slow this down, they don't offer the same level of permanence as stone's inherent resistance.

Imagine a wooden fence post and a stone pillar exposed to the same elements. The wood, over time, will soften, crack, and eventually crumble as fungi and bacteria work their way through its fibers. The stone pillar, however, will remain steadfast, its surface perhaps weathered by wind and rain, but its structural integrity largely intact. This stark contrast illustrates the power of stone's resistance to rot, a quality that has made it the material of choice for enduring monuments and structures throughout history.

Polyethylene Glycol Wood Treatment: Optimal Soaking Duration Explained

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Weathering Tolerance: Stone withstands extreme weather; wood warps, cracks, or erodes faster

Stone's resilience in the face of extreme weather is a testament to its molecular structure. Unlike wood, which is composed of organic cellulose and lignin, stone is a dense, inorganic material with tightly bound mineral crystals. This fundamental difference means stone can endure temperature fluctuations, UV radiation, and moisture without the same degree of expansion, contraction, or degradation. For instance, granite, a common building stone, has a thermal expansion coefficient of approximately 4-10 x 10^-6 per °C, whereas wood can expand or contract by up to 0.4% with moisture changes. This inherent stability allows stone to maintain its integrity in environments where wood would warp, crack, or rot.

Consider the practical implications for outdoor structures. A wooden fence exposed to alternating wet and dry conditions will absorb moisture, causing fibers to swell and shrink. Over time, this leads to splitting and warping, often requiring replacement within 10–15 years. In contrast, a stone wall, such as those found in ancient fortifications, remains largely unaffected by these cycles. For homeowners, choosing stone for patios, walkways, or retaining walls can reduce long-term maintenance costs. To maximize durability, select stones with low porosity, like quartzite or slate, and ensure proper drainage to prevent water pooling, which can still cause erosion in less dense stones.

The persuasive case for stone lies in its longevity and aesthetic appeal. While wood may offer initial cost savings, its susceptibility to weathering means frequent repairs or replacements. Stone, however, retains its structural and visual integrity for centuries. Take the example of the Great Wall of China, where stone sections have outlasted their wooden counterparts by millennia. For modern applications, combining stone with metal reinforcements can further enhance durability. Architects and builders should prioritize stone in areas prone to extreme weather, such as coastal regions or high-altitude environments, where wood’s limitations are most pronounced.

A comparative analysis highlights the role of moisture resistance. Wood’s hygroscopic nature allows it to absorb up to 25% of its weight in water, leading to fungal growth, insect damage, and decay. Stone, particularly non-porous varieties like marble or basalt, repels moisture, preventing these issues. However, not all stones are equal; limestone, for instance, is more susceptible to acid rain due to its calcium carbonate composition. To mitigate this, apply sealants every 2–3 years, especially in acidic environments. Conversely, wood can be treated with preservatives, but these require reapplication every 1–2 years and are less effective in extreme conditions.

Finally, a descriptive exploration reveals stone’s timeless beauty under duress. Imagine a stone monument standing firm after a century of storms, its surface weathered yet intact, while nearby wooden structures have long succumbed to rot and decay. This endurance is not just practical but symbolic, representing permanence in an ever-changing world. For those seeking to build or restore structures with longevity, stone offers a solution that transcends generations. Pair it with thoughtful design—such as overhangs to shield from rain or ventilation to prevent moisture buildup—and the result is a masterpiece of both form and function.

Drying Wet Seasoned Wood: Timeframe and Tips for Optimal Results

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Chemical Stability: Stone resists chemical reactions; wood breaks down under acids or moisture

Stone's longevity compared to wood is largely due to its inherent chemical stability. Unlike wood, which is composed of organic compounds like cellulose and lignin, stone is primarily made up of inorganic minerals such as quartz, feldspar, and mica. These minerals are highly resistant to chemical reactions, making stone impervious to the corrosive effects of acids, bases, and other reactive substances. For instance, a granite countertop can withstand spills of lemon juice (pH 2) or vinegar (pH 3) without degradation, whereas a wooden surface would quickly show signs of etching or discoloration.

Consider the practical implications of this stability in outdoor environments. Stone monuments, like the ancient Egyptian pyramids, have endured for millennia, exposed to rain, wind, and temperature fluctuations. Rainwater, often slightly acidic due to dissolved carbon dioxide (forming carbonic acid with a pH around 5.6), poses little threat to stone. In contrast, wooden structures, such as fences or decks, require regular treatment with sealants or preservatives to slow down moisture-induced rot and fungal growth. A single untreated wooden post can decay within 5–10 years in humid climates, while a stone pillar remains structurally sound for centuries.

To illustrate the chemical vulnerability of wood, examine its response to moisture. When wood absorbs water, the hydrogen bonds between cellulose fibers weaken, causing swelling and warping. Prolonged exposure leads to hydrolysis, where water molecules break down lignin, the natural "glue" holding wood cells together. This process accelerates in acidic conditions, such as soil with a pH below 5.5, common in regions with high rainfall. Stone, however, remains unaffected by these mechanisms. Its crystalline structure is held together by strong ionic or covalent bonds, which do not hydrolyze under normal environmental conditions.

For those seeking to maximize the lifespan of wooden structures, proactive measures are essential. Apply a water-repellent sealant annually, ensuring it penetrates the wood’s surface to create a barrier against moisture. Avoid using acidic cleaners (e.g., bleach or ammonia-based solutions) that can degrade the wood’s surface. Instead, opt for pH-neutral soaps or specialized wood cleaners. For acidic soil environments, consider installing stone or concrete bases beneath wooden posts to minimize direct contact with the ground. These steps, while effective, highlight the inherent advantage of stone: it requires no such maintenance to resist chemical degradation.

In summary, stone’s chemical stability stems from its inorganic composition, which resists reactions with acids, moisture, and other environmental agents. Wood, being organic, is inherently susceptible to breakdown under these conditions, necessitating protective interventions. While wood can be preserved with careful maintenance, stone’s natural resilience makes it a superior choice for applications requiring long-term durability without ongoing treatment. This fundamental difference in chemical behavior explains why stone endures where wood falters.

Durability of Wooden Decks: Lifespan, Maintenance, and Longevity Tips

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$225.75

Biological Immunity: Stone is impervious to pests; wood is prone to insect damage

Stone's biological immunity to pests is a key factor in its longevity compared to wood. Unlike wood, which is a natural habitat and food source for insects like termites, carpenter ants, and beetles, stone is chemically and structurally inert. These pests, equipped with enzymes capable of breaking down cellulose in wood, find nothing to digest in stone's mineral composition. This fundamental difference in material vulnerability means stone structures, from ancient pyramids to modern countertops, remain unscathed by the biological threats that relentlessly degrade wood.

Consider the practical implications for homeowners. Wood, while aesthetically pleasing and versatile, requires vigilant maintenance to deter pests. This includes regular inspections, chemical treatments like borate sprays or pressure-treated lumber, and environmental modifications to reduce moisture—a magnet for wood-boring insects. Stone, on the other hand, demands no such interventions. Its imperviousness to pests translates to lower long-term costs and less reliance on potentially toxic preservatives, making it a more sustainable choice for load-bearing structures, exterior cladding, or even garden features.

A comparative analysis highlights the scale of wood's susceptibility. Termites alone cause over $5 billion in property damage annually in the U.S., often going undetected until structural integrity is compromised. In contrast, stone's resistance to biological degradation ensures that even millennia-old structures like the Great Wall of China’s stone sections remain intact. For builders and architects, this disparity underscores the importance of material selection: wood may be renewable, but stone’s pest immunity offers unparalleled durability in high-risk environments.

To maximize wood’s lifespan despite its vulnerabilities, homeowners can adopt proactive measures. Seal all exposed wood with epoxy resins or paint to create a physical barrier against insects. Store firewood at least 20 feet from structures and elevate it off the ground to disrupt pest migration. For new constructions, opt for naturally resistant species like cedar or redwood, though even these require periodic treatment. While these steps mitigate risk, they also illustrate the inherent advantage of stone: its passive, maintenance-free resistance to the very forces that demand wood’s constant protection.

Ultimately, the choice between stone and wood hinges on balancing aesthetics, cost, and durability. Wood’s warmth and workability make it ideal for interior finishes or temporary structures, but its biological vulnerabilities necessitate ongoing care. Stone, though heavier and more expensive upfront, offers a pest-proof solution for applications where longevity is non-negotiable. By understanding this biological immunity, one can make informed decisions that align material properties with functional needs, ensuring structures endure not just years, but centuries.

Drying Wet Seasoned Wood: Understanding the Timeframe for Optimal Results

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Stone lasts longer than wood because it is more resistant to weathering, decay, and biological damage. Stone is non-organic and does not rot, while wood is susceptible to moisture, insects, and fungi.

Stone is composed of minerals that are chemically stable and less reactive to environmental factors like water, temperature, and UV radiation. Wood, being organic, contains cellulose and lignin, which break down over time when exposed to these elements.

Yes, stone can withstand extreme weather conditions better than wood because it is denser, harder, and less prone to expansion or contraction due to temperature changes. Wood, on the other hand, can warp, crack, or degrade when exposed to prolonged heat, cold, or moisture.