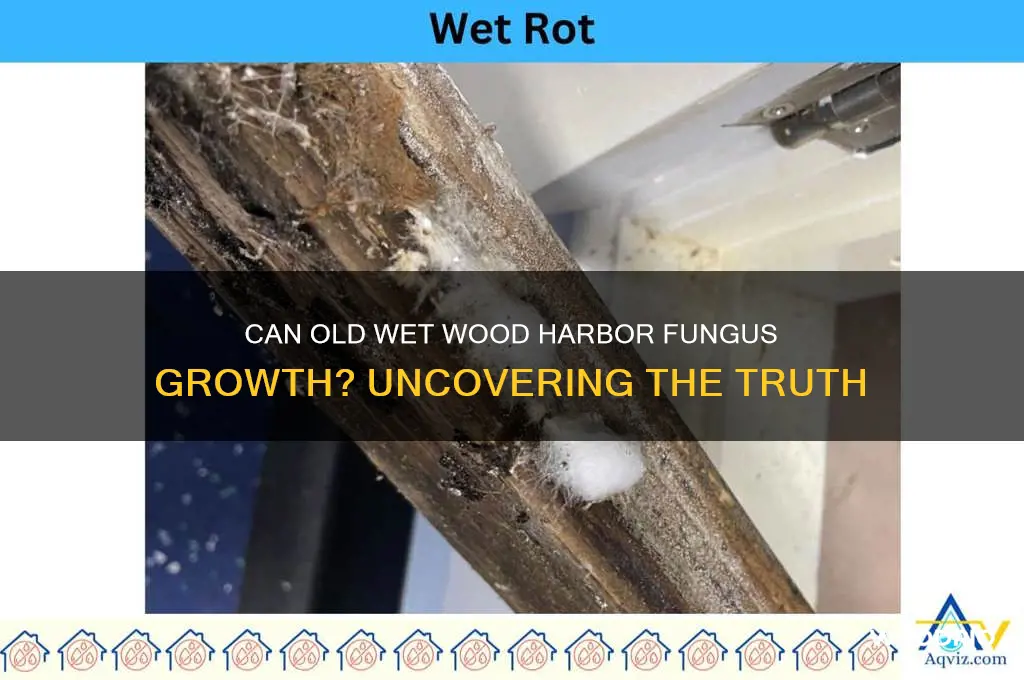

Fungus thrives in environments that provide moisture, organic matter, and warmth, making old wet wood an ideal habitat for its growth. As wood ages and becomes damp, whether due to rain, humidity, or water damage, it creates the perfect conditions for fungal spores to germinate and spread. Fungi break down the cellulose and lignin in wood, causing decay and weakening its structure over time. Common types of wood-decay fungi include brown rot, white rot, and soft rot, each with distinct effects on the wood’s appearance and integrity. Understanding the relationship between fungus and old wet wood is crucial for preventing damage to structures, furniture, and natural ecosystems, as well as for appreciating the role fungi play in nutrient cycling and decomposition.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Growth Environment | Old, wet wood provides ideal conditions for fungal growth due to high moisture content and organic material. |

| Moisture Requirement | Fungi thrive in environments with >50% moisture content; wet wood exceeds this threshold. |

| Nutrient Source | Wood serves as a rich source of cellulose and lignin, which fungi decompose for nutrients. |

| Common Fungal Types | Molds (e.g., Aspergillus, Penicillium), wood-decay fungi (e.g., Trametes, Serpula). |

| Temperature Range | Optimal growth occurs between 20°C and 30°C (68°F–86°F), though some species tolerate colder or warmer conditions. |

| pH Preference | Most wood-decay fungi prefer slightly acidic to neutral pH (4.0–7.0). |

| Growth Rate | Varies by species; some fungi colonize wood within weeks, while others take months. |

| Visible Signs | Discoloration, soft or crumbly wood, mushroom-like fruiting bodies, musty odor. |

| Health Risks | Certain fungi produce allergens or mycotoxins, posing respiratory or systemic health risks. |

| Prevention Methods | Reduce moisture (e.g., proper ventilation, waterproofing), remove decaying wood, use fungicides. |

| Ecological Role | Fungi play a crucial role in decomposing wood, recycling nutrients in ecosystems. |

Explore related products

$15.2 $20.64

What You'll Learn

Ideal Conditions for Fungus Growth

Fungus thrives in environments that provide the right balance of moisture, nutrients, and temperature. Old, wet wood is a prime candidate for fungal growth because it often meets these criteria. The cellulose and lignin in wood serve as a rich food source for fungi, while the moisture trapped within the wood fibers creates an ideal habitat. However, not all wet wood will foster fungus; the conditions must be just right. Understanding these ideal conditions can help predict where and why fungus appears, and how to prevent it.

Moisture: The Non-Negotiable Factor

Fungi require water to grow, and old wet wood provides a consistent moisture source. Wood with a moisture content above 20% is particularly susceptible, as this level allows fungal spores to germinate and spread. In practical terms, wood exposed to leaks, high humidity, or poor ventilation is at risk. For instance, a damp basement or a rain-soaked deck board can become a fungal hotspot within weeks. To mitigate this, maintain wood moisture levels below 19% through proper sealing, drainage, and airflow. Dehumidifiers or moisture meters can be useful tools for monitoring at-risk areas.

Temperature: The Goldilocks Zone

Fungi are most active in temperatures between 68°F and 86°F (20°C to 30°C), though some species tolerate cooler or warmer conditions. Old wood in temperate climates, such as attics or crawl spaces, often falls within this range, especially if insulated by surrounding materials. Interestingly, freezing temperatures do not kill fungal spores—they merely slow growth. Once temperatures rise, dormant fungi can resume activity. To discourage growth, ensure wood is stored in areas with stable, cooler temperatures, ideally below 60°F (15°C), and avoid stacking wood in ways that trap heat.

Oxygen and pH: The Supporting Roles

While less discussed, oxygen and pH levels also influence fungal growth. Fungi are aerobic organisms, meaning they require oxygen to metabolize wood. Dense, waterlogged wood may limit oxygen availability, slowing growth but not always preventing it. Additionally, fungi prefer slightly acidic to neutral pH levels (4.0 to 7.0). Wood treated with alkaline preservatives, like copper azole, can inhibit growth by altering pH. For homeowners, this means avoiding over-saturation of wood and considering pH-altering treatments for high-risk areas.

Preventive Measures: A Proactive Approach

Preventing fungal growth in old wet wood requires addressing its ideal conditions. Start by reducing moisture through regular inspections and repairs of leaks or water damage. Apply water-repellent sealants to exposed wood surfaces, especially outdoors. For indoor wood, ensure proper ventilation and use moisture barriers in basements or crawl spaces. Temperature control can be achieved by insulating wood storage areas or using fans to promote airflow. Finally, treat wood with fungicides or natural repellents like tea tree oil for added protection. By disrupting the ideal conditions, you can significantly reduce the likelihood of fungal infestations.

Lace Hydrangeas: New or Old Wood Growth Explained

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Types of Fungi in Wet Wood

Fungi thrive in damp, decaying wood, breaking it down into simpler compounds and playing a crucial role in nutrient cycling. Wet wood provides the ideal environment for various fungal species, each with unique characteristics and ecological functions. Understanding these types not only sheds light on their role in ecosystems but also helps in managing wood decay in structures and landscapes.

Saprotrophic Fungi: The Primary Decomposers

These fungi are the first responders to wet wood, secreting enzymes that break down cellulose and lignin, the primary components of wood. *Trichoderma* and *Aspergillus* are common examples, often appearing as fuzzy, greenish or black patches. They are essential for recycling nutrients but can weaken wooden structures over time. To mitigate their impact, ensure wood is treated with fungicides or kept in well-ventilated areas to reduce moisture accumulation.

Brown Rot and White Rot: Specialized Wood Destroyers

Brown rot fungi, such as *Postia placenta*, target cellulose, leaving behind a brown, crumbly residue. White rot fungi, like *Trametes versicolor*, break down both cellulose and lignin, resulting in a bleached, stringy appearance. These fungi are highly efficient decomposers, often found in older, waterlogged wood. For homeowners, identifying these types early is key—inspect wood for color changes or unusual textures, and replace affected materials promptly to prevent structural damage.

Mold Fungi: The Surface Dwellers

Molds, including *Penicillium* and *Cladosporium*, grow on the surface of wet wood, forming visible colonies that range from green to black. While they don’t penetrate deeply, they indicate high moisture levels and can compromise indoor air quality. To control mold, reduce humidity below 60% using dehumidifiers, and clean affected areas with a 1:10 bleach-water solution. Always wear protective gear when handling mold to avoid respiratory issues.

Bracket Fungi: The Wood-Eating Architects

Bracket fungi, or polypores, form shelf-like structures on decaying wood, often signaling advanced decomposition. Species like *Fomes fomentarius* and *Ganoderma applanatum* are common culprits. These fungi are harder to eradicate once established, as they derive nutrients from deep within the wood. Regularly inspect trees and wooden structures for conk formations, and remove infected wood to prevent further spread. For trees, consult an arborist to assess the extent of damage.

Mycorrhizal Fungi: The Hidden Partners

While primarily associated with living trees, mycorrhizal fungi like *Amanita* and *Laccaria* can also colonize wet wood near tree roots. These fungi form symbiotic relationships, aiding nutrient uptake in exchange for carbohydrates. Though not directly harmful to wood, their presence highlights the interconnectedness of fungal ecosystems. Encouraging mycorrhizal growth in gardens can improve plant health, but avoid excessive watering to prevent wood decay in nearby structures.

By recognizing these fungal types, you can better manage wet wood environments, whether in natural settings or built structures. Each fungus has a unique role, and addressing them requires tailored strategies—from moisture control to targeted removal.

Discovering Brenda Woods' Age: A Comprehensive Look at Her Life

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Impact on Wood Structure

Fungal growth in old wet wood initiates a cascade of structural changes, beginning with the colonization of hyphae—microscopic, thread-like structures that penetrate the wood’s cellular matrix. These hyphae secrete enzymes that break down cellulose and lignin, the primary components of wood, effectively weakening its internal framework. Over time, this degradation reduces wood density, making it softer and more brittle. For instance, a study on oak timber exposed to *Serpula lacrymans* (dry rot fungus) showed a 30% loss in compressive strength after just six months of infestation. This process is irreversible, as the fungus alters the wood’s load-bearing capacity, rendering it structurally unsound for construction or support purposes.

To mitigate fungal damage, early detection is critical. Inspect wood for telltale signs such as discoloration, musty odors, or a crumbly texture. If fungal growth is suspected, reduce moisture levels immediately by improving ventilation or using dehumidifiers to maintain humidity below 60%. For minor infestations, apply fungicidal treatments like borate-based solutions at a concentration of 10% to penetrate the wood and inhibit fungal activity. However, caution must be exercised: over-application of chemicals can leach into the environment, posing risks to soil and water systems. Always follow manufacturer guidelines and wear protective gear during treatment.

Comparatively, the impact of fungal decay on softwoods versus hardwoods differs significantly. Softwoods, like pine, are more susceptible due to their lower density and higher resin content, which fungi can exploit more easily. Hardwoods, such as teak, possess natural resistance due to higher lignin content and denser grain structure. However, prolonged moisture exposure can still compromise even the most resilient hardwoods. For example, a comparative study found that pine samples lost 40% of their tensile strength after fungal exposure, while teak samples lost only 15% under identical conditions. This highlights the importance of species selection in moisture-prone environments.

Descriptively, the transformation of wood under fungal attack is both fascinating and destructive. Initially, the wood may appear unchanged, but as hyphae spread, it develops a cracked, checkerboard-like pattern known as cubical fracture. Advanced decay manifests as a spongy, stringy texture, often accompanied by fungal fruiting bodies (mushrooms or brackets) on the surface. In extreme cases, the wood becomes hollow, with only a thin outer shell remaining. This stage is particularly dangerous in structural applications, as the wood can collapse under minimal stress. Regular monitoring and maintenance are essential to prevent such outcomes, especially in historic buildings or wooden infrastructure.

Persuasively, the economic and safety implications of fungal damage demand proactive measures. In the U.S. alone, wood decay caused by fungi costs the construction industry over $10 billion annually in repairs and replacements. Homeowners and builders must prioritize moisture control through proper waterproofing, regular inspections, and prompt remediation. Investing in preventive measures, such as using pressure-treated wood or installing vapor barriers, is far more cost-effective than addressing advanced decay. By understanding and addressing the structural impact of fungal growth, we can preserve the integrity of wooden materials and ensure their longevity in various applications.

The Wood Brothers' Age: Unveiling the Timeless Legacy of the Siblings

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$22.99 $27.86

Preventing Fungal Infestation

Fungus thrives in damp, dark environments, making old wet wood a prime breeding ground. To prevent fungal infestation, start by addressing moisture—the lifeblood of fungal growth. Wood with a moisture content above 20% is particularly susceptible, so use a moisture meter to assess risk areas. If wood is already damp, improve ventilation by spacing items apart and ensuring air circulates freely. For outdoor structures, apply water-repellent sealants annually to create a barrier against moisture infiltration.

Next, consider the role of sunlight in deterring fungal growth. Fungi prefer low-light conditions, so strategically expose wood to natural light whenever possible. Trim overhanging branches or relocate stored wood to sunnier areas. If sunlight is limited, install UV-emitting lights near susceptible surfaces. These lights mimic natural sunlight, disrupting fungal growth cycles without harming humans or pets. Combine this with regular cleaning to remove organic debris, which fungi feed on, from wood surfaces.

Chemical treatments offer another layer of protection, but choose wisely to avoid environmental harm. Borate-based solutions, such as borax or boric acid, penetrate wood fibers and remain active for years, inhibiting fungal enzymes. Apply these at a concentration of 1–2% in water, ensuring thorough coverage. For smaller items, soak in the solution for 20 minutes before drying. Alternatively, use commercial fungicides labeled for wood treatment, following manufacturer instructions for dosage and application frequency. Always wear gloves and a mask during application.

Finally, adopt proactive maintenance habits to keep wood in optimal condition. Inspect wooden structures quarterly for signs of discoloration, softness, or musty odors—early indicators of fungal activity. Repair leaks promptly, as even minor water intrusion can trigger infestations. For high-risk areas like basements or crawl spaces, invest in dehumidifiers to maintain humidity below 50%. Pair this with periodic wood treatment to reinforce defenses. By combining environmental control, chemical intervention, and vigilant upkeep, you can effectively safeguard wood against fungal threats.

Hydrangeas: Blooming on Old or New Wood Explained

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Health Risks of Wood Fungi

Fungi thrive in damp, decaying wood, creating not only structural concerns but also significant health risks for humans. As wood ages and moisture accumulates, it becomes an ideal breeding ground for various fungal species, some of which produce harmful spores and mycotoxins. These microscopic particles can become airborne, infiltrating indoor environments and posing serious health threats, particularly to vulnerable populations.

The Respiratory Hazard: A Silent Intruder

Inhalation of fungal spores is a primary health concern. When disturbed, whether by construction, cleaning, or natural degradation, contaminated wood releases spores into the air. Prolonged exposure to these spores can lead to a range of respiratory issues. For instance, *Aspergillus* and *Penicillium*, common wood-dwelling fungi, are known to cause allergic reactions, asthma exacerbations, and even severe lung infections in immunocompromised individuals. A study published in the *Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine* revealed that workers exposed to fungal spores in water-damaged buildings had a significantly higher prevalence of respiratory symptoms, with 30% reporting chronic bronchitis and 20% experiencing asthma-like symptoms.

Mycotoxins: A Hidden Danger

Beyond spores, certain wood fungi produce mycotoxins, toxic compounds that can have severe health implications. These toxins can contaminate indoor air and surfaces, leading to various health issues. For example, the fungus *Stachybotrys chartarum*, often found in water-damaged wood, produces trichothecene mycotoxins. Exposure to these toxins has been linked to a condition known as 'sick building syndrome,' characterized by symptoms such as headaches, dizziness, fatigue, and irritation of the eyes, nose, and throat. In severe cases, mycotoxin exposure can lead to long-term health problems, including neurological damage and immune system suppression.

Preventive Measures: A Proactive Approach

Addressing the health risks associated with wood fungi requires a multi-faceted strategy. Firstly, maintaining indoor humidity below 60% discourages fungal growth. Regular inspection and prompt repair of water leaks, especially in wooden structures, are essential. When dealing with old, wet wood, personal protective equipment (PPE) such as respirators and gloves should be worn to minimize direct exposure. For individuals with respiratory conditions or weakened immune systems, avoiding areas with visible fungal growth is crucial. In cases of extensive fungal infestation, professional remediation services should be engaged to ensure safe and effective removal.

Long-Term Health Implications: A Call for Awareness

The health risks posed by wood fungi extend beyond immediate symptoms. Chronic exposure to fungal spores and mycotoxins can lead to long-term health issues, particularly in susceptible individuals. Children, the elderly, and those with pre-existing respiratory conditions are at higher risk. Prolonged exposure has been associated with the development of chronic respiratory diseases, including bronchitis and hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Moreover, certain mycotoxins have been classified as potential carcinogens, underscoring the importance of early detection and remediation to prevent severe health consequences.

In summary, the presence of fungi in old, wet wood is not merely a structural concern but a significant health hazard. From respiratory ailments to long-term toxic effects, the impact on human health can be severe. By understanding the risks and implementing preventive measures, individuals can protect themselves and their families from the hidden dangers lurking in damp wooden environments. This knowledge is particularly crucial for homeowners, builders, and healthcare professionals in mitigating the health risks associated with wood fungi.

Reclaimed Barn Wood: A Profitable Business for Companies?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, fungus thrives in old wet wood due to the moisture and organic material, which provide ideal conditions for fungal growth.

Common fungi found in old wet wood include mold, mildew, and wood-decay fungi like dry rot and brown rot, which break down cellulose and lignin in the wood.

To prevent fungal growth, reduce moisture by ensuring proper ventilation, fixing leaks, and using waterproof treatments. Regularly inspect and dry the wood, and consider using fungicides if necessary.