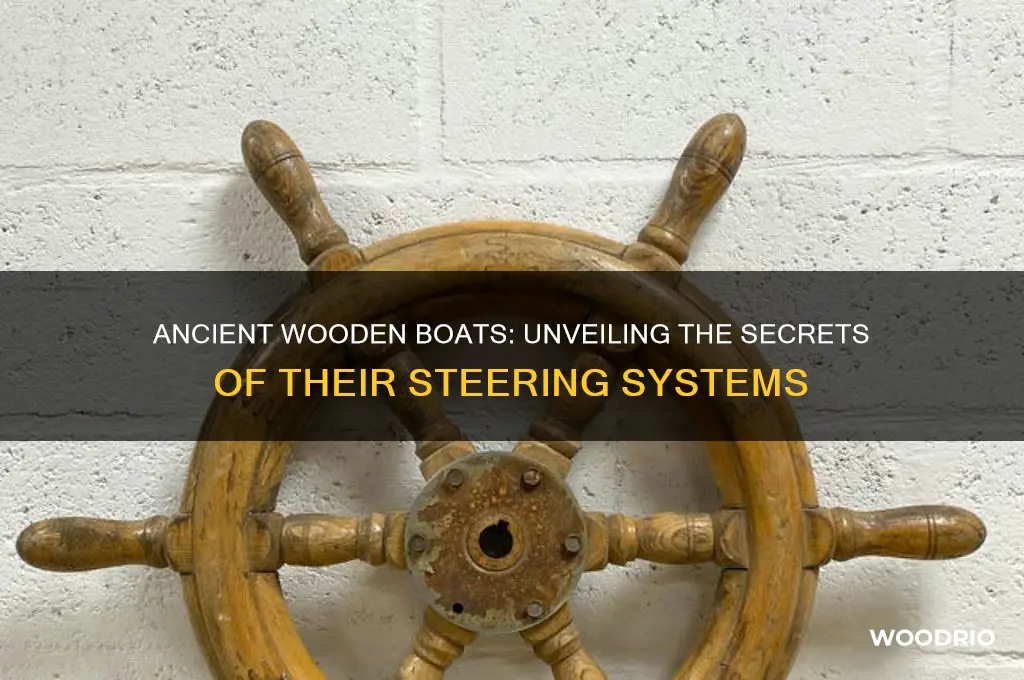

Old wooden boats employed a variety of steering mechanisms, with the most common being the tiller and rudder system. A rudder, typically a flat wooden board or plank, was attached to the stern of the vessel and controlled by a tiller, a lever or handle connected to the top of the rudder. The helmsman would grasp the tiller and apply pressure to one side or the other, causing the rudder to pivot and redirect the water flow, thereby changing the boat's direction. This simple yet effective system allowed sailors to navigate waterways with precision, relying on their skill and the boat's responsiveness to the rudder's movements. Other methods, such as side-mounted oars or steering boards, were also used in certain cultures or for specific types of vessels, but the tiller and rudder remained the dominant steering mechanism for centuries.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Steering Mechanism | Tiller |

| Tiller Description | A long wooden lever attached to the top of the rudder post, extending into the boat. The helmsman pushed or pulled the tiller to turn the rudder. |

| Rudder Type | Hinged wooden plank or board, often made of oak or elm, attached to the stern post. |

| Rudder Control | Direct control via the tiller, requiring physical strength and skill to maneuver, especially in larger vessels. |

| Steering Position | Typically at the stern (rear) of the boat, often in an open area exposed to the elements. |

| Common in | Viking longships, medieval cogs, and early sailing ships up to the 17th century. |

| Advantages | Simple design, easy to repair with available materials, and effective for smaller vessels. |

| Disadvantages | Limited precision, physically demanding, and less effective in rough seas or larger ships. |

| Evolution | Gradually replaced by the wheel and cable systems in the 17th and 18th centuries for larger vessels, though tillers remained common in smaller boats. |

| Historical Significance | Fundamental to early maritime navigation, enabling exploration and trade across ancient civilizations. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Tiller Steering: Simple lever attached to rudder, controlled manually by helmsman for direct steering

- Whale Bone Rudders: Early boats used flexible whale bone for responsive, lightweight rudder control

- Side-Mounted Oars: Oars on one side provided steering by varying rowing force

- Quarter Rudders: Small, pivoting rudders mounted at the boat’s stern for precision

- Steering Boards: Flat boards tied to the stern, precursor to modern rudders

Tiller Steering: Simple lever attached to rudder, controlled manually by helmsman for direct steering

Tiller steering, a cornerstone of maritime history, exemplifies the elegance of simplicity in boat design. At its core, a tiller is a lever directly connected to the rudder, the submerged blade that redirects water flow to change a vessel's direction. This system, controlled manually by the helmsman, offers a direct, unmediated connection between the sailor's hands and the boat's course. Unlike modern wheel-based systems, which often involve cables, gears, or hydraulics, tiller steering relies on pure mechanical advantage, making it both intuitive and reliable. Its enduring presence in small craft and traditional wooden boats underscores its effectiveness in a variety of conditions, from calm lakes to open seas.

To operate a tiller effectively, the helmsman must understand its counterintuitive nature: pushing the tiller to the right turns the rudder—and thus the boat—to the left, and vice versa. This requires a blend of physical strength and finesse, particularly in larger vessels or adverse weather. For beginners, practicing in calm waters is essential to develop muscle memory and a sense of how the boat responds. A practical tip is to position oneself slightly forward of the tiller, using body weight to assist in larger movements while maintaining fine control through hand adjustments. This balance between brute force and precision is what makes tiller steering both challenging and rewarding.

Comparatively, tiller steering stands in stark contrast to wheel-based systems, which often amplify small inputs through mechanical advantage. While wheels offer ease of use and reduced physical strain, tillers provide immediate feedback and a tactile sense of the water’s resistance. This direct connection allows skilled helmsmen to "feel" the rudder’s interaction with the water, enabling subtle adjustments that can improve efficiency and responsiveness. For sailors seeking a deeper connection with their craft, tiller steering is unparalleled in its ability to foster a symbiotic relationship between sailor and sea.

Despite its simplicity, tiller steering is not without limitations. Its effectiveness diminishes in larger vessels, where the force required to move the rudder becomes impractical for a single individual. Additionally, prolonged use in rough conditions can be physically demanding, leading to fatigue. However, for small to medium-sized wooden boats—such as dinghies, skiffs, or classic sailboats—tiller steering remains a practical and efficient choice. Modern adaptations, such as tiller extensions or ergonomic grips, can enhance comfort without compromising the system’s inherent advantages.

In conclusion, tiller steering is a testament to the principle that the best tools are often the simplest. Its direct, hands-on approach offers sailors a level of control and feedback that modern systems struggle to replicate. While it may not suit every vessel or situation, its enduring popularity in traditional and recreational boating highlights its timeless appeal. For those willing to embrace its unique demands, tiller steering provides not just a means of navigation, but a deeper, more intimate experience of the art of sailing.

Forsythia Blooming Secrets: New Wood vs. Old Wood Explained

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Whale Bone Rudders: Early boats used flexible whale bone for responsive, lightweight rudder control

In the annals of maritime history, the use of whale bone in rudder construction stands as a testament to human ingenuity and the symbiotic relationship between early sailors and their environment. Long before the advent of modern materials, shipwrights sought lightweight, durable, and responsive solutions for steering their vessels. Whale bone, harvested from the jaws and ribs of these marine giants, emerged as an ideal material for rudders due to its unique combination of flexibility and strength. This natural composite allowed for precise control, even in the unpredictable waters of ancient trade routes.

Consider the mechanics of a whale bone rudder: its elasticity enabled it to bend under pressure, reducing the risk of breakage in rough seas, while its inherent rigidity provided the necessary force to alter a vessel’s course. For instance, Viking longships, renowned for their agility, often incorporated whale bone into their steering systems. The material’s lightweight nature minimized drag, enhancing both speed and maneuverability—crucial advantages during raids or long-distance voyages. To replicate this design today, modern boat builders might experiment with synthetic composites that mimic whale bone’s properties, ensuring ethical and sustainable practices.

However, the use of whale bone was not without challenges. Its procurement required skill and often involved dangerous whaling expeditions, limiting its accessibility to coastal communities with established maritime traditions. Additionally, the material’s susceptibility to saltwater degradation necessitated regular maintenance, such as coating with animal fats or tar to prolong its lifespan. For enthusiasts seeking to restore or recreate historical vessels, sourcing ethically obtained antique whale bone or using 3D-printed bioplastics can serve as viable alternatives, preserving the spirit of the original design without ecological harm.

The legacy of whale bone rudders extends beyond their functional role, offering a window into the cultural and technological priorities of early seafaring societies. Their adoption reflects a deep understanding of natural materials and a commitment to optimizing performance in the face of resource constraints. By studying these innovations, contemporary designers can draw inspiration for creating lightweight, responsive steering systems that balance tradition with modernity. Whether for historical reenactments or cutting-edge maritime engineering, the principles behind whale bone rudders remain remarkably relevant.

Are Vintage Wood Levels Valuable? A Collector's Guide to Worth

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Side-Mounted Oars: Oars on one side provided steering by varying rowing force

One of the earliest and most intuitive methods of steering in old wooden boats involved side-mounted oars. Unlike modern rudders, which are separate mechanisms, these oars served a dual purpose: propulsion and navigation. Positioned on one side of the vessel, typically the starboard (right) side, they allowed rowers to control direction by varying the force applied to each stroke. This system was particularly common in small to medium-sized boats, such as Viking longships or ancient Egyptian vessels, where simplicity and efficiency were paramount. By pulling harder on one oar or ceasing effort on another, sailors could pivot the boat or maintain a straight course without additional steering tools.

To effectively use side-mounted oars for steering, rowers needed to coordinate their efforts with precision. For instance, to turn right, the rower on the starboard side would pull harder or more frequently, while the opposite oar might be lifted or used minimally. This imbalance in force caused the boat to veer in the desired direction. Conversely, to turn left, the rower would either reduce effort or switch to the other side if oars were available. This method required skill and practice, as overcorrection could lead to erratic movements. Practical tips for beginners include starting with gentle strokes and gradually increasing force to understand the boat’s response, much like learning to balance a bicycle.

A key advantage of side-mounted oars was their adaptability to various water conditions. In calm waters, subtle adjustments sufficed for minor course corrections. In rougher seas, rowers could apply more force to counteract waves or currents, using the oars as both stabilizers and steering tools. However, this system had limitations. Larger vessels or those carrying heavy loads required more effort to maneuver, and the absence of a dedicated rudder made sharp turns challenging. Despite these drawbacks, side-mounted oars remained a reliable method for centuries, particularly in cultures where resources were limited or craftsmanship favored simplicity over complexity.

Comparing side-mounted oars to later steering innovations highlights their evolutionary significance. While they lacked the precision of a rudder or the efficiency of a sail-driven system, they laid the groundwork for understanding boat dynamics. The principle of creating asymmetry to induce turning is still fundamental in modern maritime design. For enthusiasts recreating historical boats or studying ancient navigation, mastering side-mounted oars offers a tangible connection to the ingenuity of early sailors. It’s a reminder that steering wasn’t always about specialized tools but often about maximizing the utility of what was already on board.

The Enigmatic Stranger: Unveiling Merlin's Mystical Woods Encounter

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Quarter Rudders: Small, pivoting rudders mounted at the boat’s stern for precision

Quarter rudders, small yet mighty, were the precision instruments of old wooden boats, offering a level of control that larger, more cumbersome systems couldn't match. Mounted at the stern, these pivoting rudders allowed sailors to navigate tight spaces and respond swiftly to changing winds or currents. Their compact design made them ideal for smaller vessels, where every inch of space was precious, and their simplicity ensured reliability even in the harshest conditions.

To understand the effectiveness of quarter rudders, consider their mechanics. Unlike larger rudders that require significant force to turn, quarter rudders pivot on a vertical axis, often controlled by a tiller or rope system. This setup minimizes friction and allows for quick adjustments, essential for maneuvering in crowded harbors or during sudden weather shifts. For instance, a sailor could easily steer a boat laden with cargo through a narrow channel by making subtle movements with the tiller, a task that would be far more challenging with a bulkier rudder.

When installing a quarter rudder, precision is key. The rudder must be mounted securely at the stern, ensuring it aligns perfectly with the boat’s keel to avoid drag or instability. A common mistake is improper balancing, which can lead to excessive strain on the steering mechanism. To avoid this, use a rudder that’s proportionate to the boat’s size—typically, the rudder blade should be about 20-30% of the boat’s beam width. Additionally, ensure the pivot point is well-lubricated to maintain smooth operation, especially in saltwater environments where corrosion is a constant threat.

One of the most compelling advantages of quarter rudders is their historical versatility. From Viking longships to medieval trading vessels, these rudders were adapted across cultures and eras. For example, Norse sailors favored quarter rudders for their ability to handle the rough seas of the North Atlantic, while Mediterranean traders appreciated their efficiency in navigating busy ports. This adaptability underscores their enduring practicality, even as maritime technology evolved.

In practice, maintaining a quarter rudder requires regular inspection and care. Check for cracks or wear in the wooden components, particularly after prolonged exposure to water. Treat the rudder with marine-grade varnish or oil to protect against rot and warping. For those restoring older boats, consider replacing worn-out rudders with modern materials like fiberglass or composite woods, which offer durability without sacrificing authenticity. By preserving this traditional steering system, sailors can experience the same precision and control that guided mariners for centuries.

Unveiling Patrice Wood's Age: A Comprehensive Look at Her Life

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Steering Boards: Flat boards tied to the stern, precursor to modern rudders

Before the advent of the hinged rudder, ancient mariners relied on steering boards—flat, oar-like structures tied to the stern of their vessels. These boards, often made from sturdy wood, were a direct extension of the boat’s hull, pivoting side to side to alter the vessel’s direction. Unlike modern rudders, which operate underwater, steering boards were partially submerged, their effectiveness dependent on both their angle and the water’s resistance. This simplicity made them accessible to early sailors, though their design limited maneuverability in rough seas or tight turns.

To use a steering board, a sailor would stand at the stern, gripping the board’s handle or rope attachment. By pushing or pulling, they could pivot the board left or right, redirecting the water flow and, consequently, the boat’s path. This method required physical strength and constant attention, as the board’s position needed frequent adjustment to maintain course. For small craft like Viking longships or Egyptian reed boats, this system sufficed, but larger vessels often employed two steering boards—one on each side—to improve control.

The limitations of steering boards are evident when compared to their successor, the hinged rudder. Because they operated at the waterline, they were prone to damage from waves or debris, and their exposed position made them vulnerable to breakage. Additionally, their reliance on lateral movement meant they were less effective in deep or fast-moving waters. Despite these drawbacks, steering boards were a critical innovation, bridging the gap between paddling and more sophisticated steering mechanisms.

For modern enthusiasts recreating ancient vessels, installing a steering board requires careful consideration. Use a flat, durable wood like oak or cedar, ensuring it’s at least 2 inches thick to withstand water pressure. Secure the board to the stern with strong ropes or leather straps, allowing for side-to-side movement but preventing vertical displacement. Test the setup in calm waters first, gradually increasing speed and wave conditions to understand its limitations. While not ideal for long voyages, steering boards offer a tangible connection to maritime history, providing insight into the ingenuity of early sailors.

Wisteria Blooming Secrets: Does It Thrive on Old Wood?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Old wooden boats typically used a tiller connected to a rudder for steering. The tiller was a lever attached to the top of the rudder, which the helmsman would push or pull to change the boat's direction.

The rudder in old wooden boats was usually made of wood, often the same type of wood as the boat's hull, such as oak or cedar. It was designed to be strong and durable to withstand water pressure.

On larger wooden ships, the tiller could be heavy and difficult to manage, so a tiller bar or whipstaff was often used. This was a longer handle or system of levers that allowed the helmsman to exert more force with less effort.

While some larger ships eventually adopted ship wheels (connected to the tiller via ropes and pulleys), most early wooden boats relied solely on tillers. Wheels became more common in the 17th and 18th centuries as shipbuilding technology advanced.