Bacteria survival on wood surfaces is a topic of interest due to wood's widespread use in various environments, from kitchens to outdoor structures. The longevity of bacteria on wood depends on several factors, including the type of bacteria, the wood's moisture content, temperature, and exposure to light or cleaning agents. Generally, bacteria can survive on wood for hours to days, with some resilient strains persisting longer under favorable conditions. Understanding these dynamics is crucial for maintaining hygiene and preventing the spread of pathogens in both residential and industrial settings.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Type of Bacteria | Survival time varies by species (e.g., E. coli, Salmonella, Staphylococcus) |

| Survival Time on Wood | Typically 2 days to 2 weeks, depending on conditions |

| Factors Affecting Survival | Moisture, temperature, wood type, and bacterial species |

| Optimal Conditions for Survival | High humidity (above 50%), room temperature (20-30°C or 68-86°F) |

| Dry Wood vs. Wet Wood | Bacteria survive longer on wet wood due to moisture retention |

| Wood Type Influence | Porous woods (e.g., pine) may harbor bacteria longer than dense woods (e.g., oak) |

| Disinfection Effectiveness | Proper cleaning with disinfectants reduces bacterial survival |

| UV Light Impact | UV light can reduce bacterial survival on wood surfaces |

| Common Bacteria on Wood | E. coli, Salmonella, Staphylococcus, and other pathogens |

| Prevention Measures | Regular cleaning, drying wood surfaces, and avoiding cross-contamination |

Explore related products

$16.49 $19.95

What You'll Learn

- Factors Affecting Survival: Moisture, temperature, wood type, and bacteria species impact how long bacteria live on wood

- Dry vs. Wet Wood: Bacteria survive longer on damp wood than on dry wood due to moisture retention

- Common Bacteria Types: E. coli, Salmonella, and Staphylococcus survival times vary on wood surfaces

- Wood Porosity: Dense woods like oak may harbor bacteria longer than porous woods like pine

- Disinfection Methods: Cleaning wood with bleach or vinegar reduces bacterial survival time effectively

Factors Affecting Survival: Moisture, temperature, wood type, and bacteria species impact how long bacteria live on wood

Bacteria survival on wood is a delicate balance influenced by a quartet of factors: moisture, temperature, wood type, and the bacterial species itself. Each element plays a critical role, often interacting in complex ways to determine how long these microorganisms persist. For instance, moisture acts as a double-edged sword—while it’s essential for bacterial metabolism, excessive dampness can dilute nutrients and promote fungal growth, which may outcompete bacteria. Conversely, dry conditions can desiccate bacterial cells, rendering them dormant or dead. Understanding these dynamics is key to predicting and controlling bacterial survival on wooden surfaces.

Temperature acts as a silent regulator, dictating the pace of bacterial activity. Mesophilic bacteria, which thrive at moderate temperatures (20°C to 40°C), can remain viable on wood for days or even weeks under optimal conditions. However, extremophiles—bacteria adapted to harsh environments—may survive longer, especially in cooler or warmer settings. For example, *Escherichia coli* can persist on wood for up to 14 days at room temperature but dies off rapidly when exposed to temperatures above 50°C. Practical tip: To reduce bacterial survival, maintain wooden surfaces in environments with temperatures outside the mesophilic range, either through heating or cooling, depending on the context.

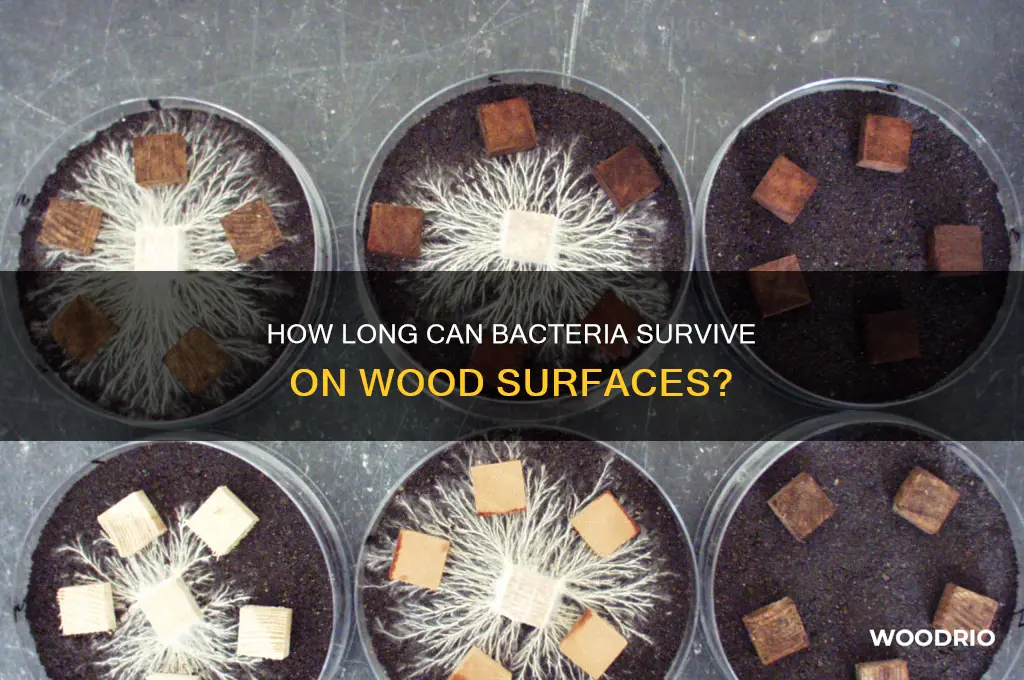

Wood type is another unsung factor, as its porosity, density, and natural antimicrobial properties vary widely. Hardwoods like oak and maple, with their dense structure, offer fewer hiding spots for bacteria compared to softwoods like pine, which are more porous. Additionally, some woods contain natural compounds that inhibit bacterial growth. For instance, cedar contains thujaplicins, which are toxic to many bacteria. When selecting wood for surfaces prone to bacterial contamination, opt for denser hardwoods or naturally antimicrobial varieties to minimize survival risks.

Finally, the bacterial species itself is a wildcard, with some strains exhibiting remarkable resilience. Gram-positive bacteria, such as *Staphylococcus aureus*, often outlast Gram-negative counterparts like *Salmonella* due to their thicker cell walls, which provide better protection against desiccation. Pathogenic bacteria, such as *Clostridium difficile*, can form spores that survive on wood for months, even under adverse conditions. To mitigate risks, identify the specific bacteria present and tailor cleaning protocols accordingly—for example, using spore-killing agents like hydrogen peroxide (3% solution) for spore-forming bacteria.

In practical terms, controlling these factors can significantly reduce bacterial survival on wood. For high-touch wooden surfaces in kitchens or healthcare settings, maintain low humidity (below 50%) and regularly clean with antimicrobial solutions. Avoid over-wetting the wood, as this can create a breeding ground for bacteria. For outdoor wooden structures, choose naturally resistant wood types and apply protective coatings to minimize moisture absorption. By addressing moisture, temperature, wood type, and bacterial species in tandem, you can effectively manage bacterial persistence and enhance hygiene in wood-rich environments.

Solar Kiln Wood Drying Time: Factors Affecting Efficiency and Duration

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Dry vs. Wet Wood: Bacteria survive longer on damp wood than on dry wood due to moisture retention

Bacteria's survival on wood surfaces is significantly influenced by moisture levels, with damp wood providing a more hospitable environment than its dry counterpart. This disparity in survival rates can be attributed to the role of moisture in bacterial metabolism and reproduction. When wood retains moisture, it creates a conducive habitat for bacteria to thrive, as water is essential for their cellular processes and nutrient absorption. In contrast, dry wood lacks the necessary moisture to support bacterial growth, leading to a shorter survival time.

From an analytical perspective, the relationship between moisture content and bacterial survival on wood can be understood through the lens of microbial ecology. Bacteria require a certain level of humidity to maintain their cellular integrity and carry out metabolic functions. Damp wood, with its higher moisture content, provides an ideal environment for bacteria to form biofilms – complex communities that enhance their resilience and longevity. These biofilms can protect bacteria from desiccation, antimicrobial agents, and other environmental stressors, allowing them to persist on wet wood surfaces for extended periods.

To minimize bacterial contamination on wood surfaces, it is essential to control moisture levels. This can be achieved through proper ventilation, dehumidification, and prompt cleaning of wet or damp wood. For instance, in food processing facilities, wooden equipment and surfaces should be thoroughly dried after cleaning to prevent bacterial growth. Additionally, sealing or treating wood with moisture-resistant coatings can help reduce its susceptibility to bacterial colonization. Regular inspection and maintenance of wooden structures in humid environments, such as bathrooms or outdoor decks, are also crucial in preventing bacterial proliferation.

A comparative analysis of dry and wet wood reveals the importance of moisture management in bacterial control. While bacteria can survive on dry wood for a limited time, typically ranging from a few hours to a few days, their longevity on damp wood can extend to several weeks or even months. This discrepancy highlights the need for targeted interventions in moisture-prone areas. For example, in healthcare settings, wooden furniture and fixtures should be regularly cleaned and dried to prevent the spread of healthcare-associated infections. Similarly, in residential environments, addressing moisture issues, such as leaks or condensation, can help mitigate bacterial growth on wooden surfaces.

In practical terms, understanding the impact of moisture on bacterial survival can inform effective cleaning and disinfection strategies. When dealing with damp wood, it is recommended to use a combination of cleaning agents and disinfectants to remove bacteria and prevent their regrowth. This may involve using detergents to break down biofilms, followed by application of EPA-registered disinfectants with bactericidal properties. For dry wood, regular dusting and occasional disinfection may suffice to maintain a hygienic surface. By tailoring cleaning protocols to the moisture content of wood, individuals can minimize bacterial contamination and promote a healthier environment. Age-specific considerations, such as protecting children or elderly individuals from bacterial exposure, further emphasize the need for vigilant moisture control and surface hygiene.

The Timeless Endurance of Wooden Sailing Ships: Secrets to Their Longevity

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Common Bacteria Types: E. coli, Salmonella, and Staphylococcus survival times vary on wood surfaces

Bacteria survival on wood surfaces is a critical concern in food preparation, healthcare, and everyday environments. Among the most notorious pathogens, E. coli, Salmonella, and Staphylococcus exhibit distinct survival patterns influenced by wood type, moisture, and temperature. Understanding these differences is essential for effective sanitation practices.

E. coli, a common cause of foodborne illness, can survive on wood surfaces for 1 to 4 weeks under favorable conditions. Its longevity is prolonged in humid environments and on untreated wood, which retains moisture. For instance, cutting boards used for raw meat pose a higher risk if not cleaned immediately. To mitigate this, sanitize wood surfaces with a solution of 1 tablespoon of bleach per gallon of water, ensuring thorough drying to deprive E. coli of the moisture it thrives on.

In contrast, Salmonella, another foodborne pathogen, typically survives on wood for 4 to 365 days, depending on factors like temperature and wood porosity. Hardwoods like maple or oak, with tighter grain structures, reduce survival times compared to softer woods like pine. A study found Salmonella persisted longer on pine surfaces at room temperature. Practical advice: avoid using wooden utensils for raw poultry and always wash them in hot, soapy water, followed by air-drying in a well-ventilated area.

Staphylococcus aureus, known for causing skin infections and food poisoning, has a shorter survival time on wood, typically hours to days. However, its ability to form biofilms on rough wood surfaces can extend its persistence. For high-risk areas like kitchens or healthcare settings, regularly sand wooden surfaces to smooth them, reducing biofilm formation. Additionally, use alcohol-based sanitizers with at least 70% alcohol for quick disinfection, especially on non-food contact surfaces.

Comparatively, while E. coli and Salmonella benefit from wood’s moisture retention, Staphylococcus is more resilient in dry conditions. This highlights the need for tailored cleaning strategies: moisture control for E. coli and Salmonella, and surface smoothing for Staphylococcus. By understanding these nuances, individuals can adopt targeted practices to minimize bacterial survival on wood, ensuring safer environments.

Root Wood Stability: When Will It Stop Affecting Your Fish Tank?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$69.95

$99.95

Wood Porosity: Dense woods like oak may harbor bacteria longer than porous woods like pine

The survival of bacteria on wood surfaces is a complex interplay of factors, with wood porosity emerging as a critical determinant. Dense woods, such as oak, present a unique challenge due to their tight grain structure, which can create microenvironments that shield bacteria from external factors like air circulation and cleaning agents. In contrast, porous woods like pine, with their more open cell structure, allow for greater air exchange and moisture evaporation, potentially reducing bacterial survival times. This distinction highlights the importance of understanding wood characteristics when assessing bacterial persistence in various environments.

From a practical standpoint, consider the implications for food preparation surfaces or children’s toys. A cutting board made of dense oak, for instance, may retain bacteria like *Salmonella* or *E. coli* for up to 4 days, especially if not properly cleaned and dried. Porous pine, however, might only harbor these pathogens for 1-2 days under similar conditions. To mitigate risk, follow these steps: clean wood surfaces with a mild bleach solution (1 tablespoon of bleach per gallon of water), rinse thoroughly, and allow to air dry completely. For high-risk areas, consider using porous woods or applying a food-safe sealant to dense woods to reduce bacterial adhesion.

Analyzing the science behind this phenomenon reveals that bacterial survival is influenced by moisture retention and surface accessibility. Dense woods retain moisture longer, providing a conducive environment for bacterial growth. Porous woods, on the other hand, wick moisture away more efficiently, depriving bacteria of the hydration they need to thrive. A study published in the *Journal of Food Protection* found that *Listeria monocytogenes* survived significantly longer on dense hardwoods compared to softwoods, underscoring the role of porosity in bacterial persistence. This insight is particularly relevant for industries like food processing and healthcare, where surface hygiene is paramount.

Persuasively, the choice of wood type can be a simple yet effective strategy for reducing bacterial contamination in everyday settings. For example, opting for pine over oak for kitchen utensils or playground equipment could lower the risk of cross-contamination. However, it’s essential to balance this with the durability and aesthetic considerations of different woods. While pine may be more bacteria-resistant, oak’s robustness makes it ideal for high-traffic areas. Pairing dense woods with rigorous cleaning protocols can offset their higher bacterial retention, ensuring both safety and longevity.

In conclusion, wood porosity plays a pivotal role in determining how long bacteria can survive on wooden surfaces. By understanding the differences between dense and porous woods, individuals and industries can make informed decisions to enhance hygiene and safety. Whether through material selection, cleaning practices, or surface treatments, addressing wood porosity is a key step in minimizing bacterial persistence and its associated risks.

Sunken Wooden Ships: Uncovering Their Remarkable Underwater Lifespan

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Disinfection Methods: Cleaning wood with bleach or vinegar reduces bacterial survival time effectively

Bacteria can survive on wood surfaces for varying durations, influenced by factors like humidity, temperature, and the type of wood. However, disinfection methods play a pivotal role in reducing their survival time. Among these, bleach and vinegar stand out as effective, accessible, and versatile solutions. Both substances disrupt bacterial cell membranes, but their application differs significantly in concentration, contact time, and suitability for specific wood types.

Bleach: A Potent Disinfectant

For heavy-duty disinfection, bleach is a go-to option. A solution of 1:10 bleach-to-water ratio (1 cup bleach per 10 cups water) is recommended for non-porous wood surfaces. Apply the solution using a cloth or spray bottle, ensuring even coverage. Allow it to sit for 5–10 minutes to penetrate bacterial cells effectively. Rinse thoroughly afterward to prevent wood discoloration or damage. Bleach is particularly effective against pathogens like *E. coli* and *Salmonella*, reducing their survival time from days to minutes. However, it’s unsuitable for untreated or unfinished wood, as it can cause drying, cracking, or bleaching. Always wear gloves and ensure proper ventilation when using bleach.

Vinegar: A Gentle Alternative

White vinegar, with its 5% acetic acid concentration, offers a milder yet effective disinfection method. Undiluted vinegar can be applied directly to wood surfaces using a spray bottle or cloth. Let it sit for 10–15 minutes before wiping dry. Vinegar is less harsh than bleach, making it ideal for finished wood furniture, cutting boards, or children’s toys. While it may not kill all bacteria as rapidly as bleach, it significantly reduces survival time, especially for common household bacteria like *Staphylococcus*. For enhanced efficacy, combine vinegar with baking soda to create a fizzy, abrasive paste that scrubs away bacteria and residue.

Comparative Analysis: Bleach vs. Vinegar

Bleach and vinegar serve different purposes in wood disinfection. Bleach is more potent but requires caution due to its corrosive nature and potential to damage wood. Vinegar, while gentler, may require more frequent application for comparable results. For high-risk areas like kitchen surfaces, bleach is preferable. For everyday maintenance or delicate wood items, vinegar is the safer choice. Both methods outperform untreated wood, where bacteria can persist for weeks under favorable conditions.

Practical Tips for Optimal Results

To maximize disinfection, clean wood surfaces with soap and water before applying bleach or vinegar to remove dirt and debris. Test a small, inconspicuous area first to check for adverse reactions. For cutting boards, alternate between bleach and vinegar treatments to avoid chemical residue buildup. Store disinfectants in labeled containers, out of reach of children and pets. Regularly disinfect high-touch wood surfaces, especially in shared spaces, to maintain hygiene and reduce bacterial survival time effectively.

By choosing the right disinfectant and following proper techniques, you can ensure wood surfaces remain clean, safe, and bacteria-free.

Wooden Matches: Burn Time Secrets and Practical Uses Revealed

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Bacteria can survive on wood surfaces for varying durations, typically ranging from a few hours to several days, depending on the type of bacteria, environmental conditions, and the moisture content of the wood.

Yes, the type of wood can influence bacterial survival. Porous woods like pine may retain moisture longer, potentially extending bacterial life, while denser woods like oak may dry out faster, reducing survival time.

Yes, bacteria generally survive longer on wet or damp wood because moisture provides a favorable environment for growth and survival. Dry wood tends to inhibit bacterial life due to lack of water.

Yes, temperature plays a significant role. Bacteria thrive in warmer conditions (20–40°C or 68–104°F) and may survive longer on wood in these temperatures. Colder temperatures can slow or stop bacterial growth.

To reduce bacterial survival, keep wood surfaces dry, clean them regularly with disinfectants, and ensure proper ventilation. UV light exposure can also help kill bacteria on wood.