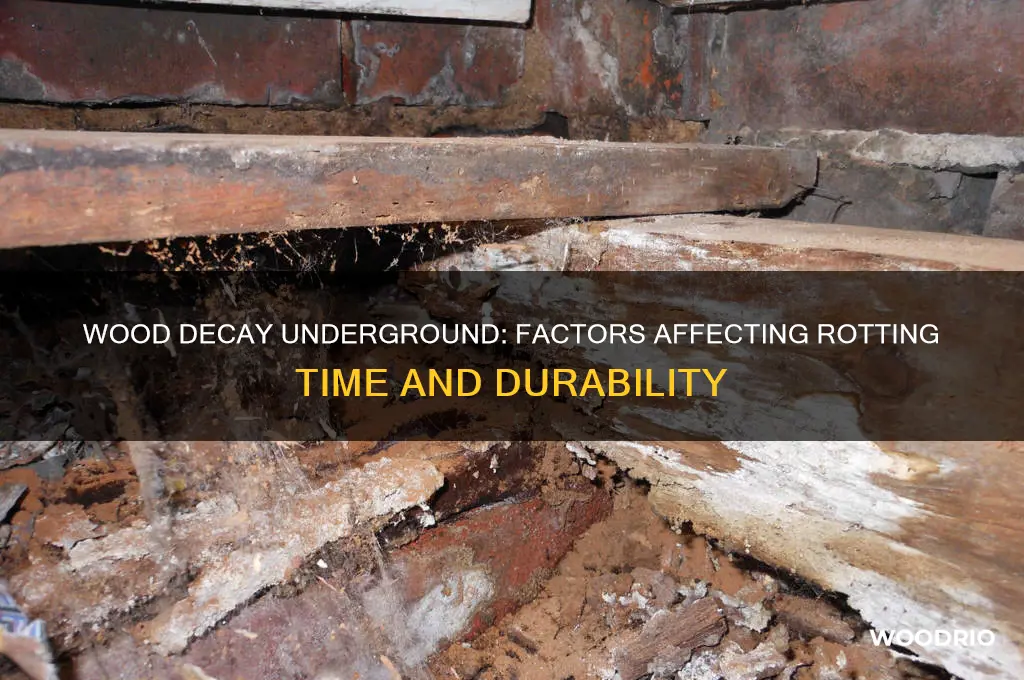

The rate at which wood rots underground depends on several factors, including the type of wood, moisture levels, soil composition, temperature, and the presence of microorganisms. Hardwoods like oak or teak generally decompose more slowly than softwoods like pine, due to their denser structure and higher natural resistance to decay. In consistently moist, warm, and oxygen-rich environments, wood can begin to rot within a few years, while in drier or colder conditions, it may take decades or even centuries. Underground, where oxygen is limited, the decay process is typically slower, often relying on anaerobic bacteria and fungi. Understanding these variables is crucial for predicting wood longevity in various burial conditions.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Moisture Levels: High moisture speeds up wood decay underground

- Soil Type: Clay soils retain moisture, accelerating rot compared to sandy soils

- Wood Type: Softwoods rot faster than hardwoods due to lower density

- Temperature Effects: Warmer climates increase bacterial activity, hastening decomposition

- Pest Influence: Termites and fungi significantly shorten wood’s lifespan underground

Moisture Levels: High moisture speeds up wood decay underground

Wood buried underground doesn't simply vanish overnight. Decay is a complex process influenced heavily by moisture levels. Imagine a damp, shadowy forest floor – the perfect breeding ground for fungi and bacteria, the primary decomposers of wood. This same principle applies underground. High moisture content creates an ideal environment for these microorganisms to thrive, accelerating the breakdown of cellulose and lignin, the building blocks of wood.

Think of it as a feast for these tiny organisms, with moisture acting as the invitation.

The relationship between moisture and decay isn't linear. While some moisture is necessary for microbial activity, excessively wet conditions can actually hinder decomposition. Waterlogged wood can become anaerobic, depriving the decomposers of the oxygen they need to function efficiently. The sweet spot lies in consistently damp, but not saturated, conditions. This allows for optimal microbial activity without drowning the very organisms responsible for the breakdown.

Think of it like a well-watered garden – too little water, and plants wither; too much, and they rot.

Understanding this moisture-decay relationship has practical implications. For instance, in construction, treating wood with preservatives that repel moisture can significantly extend its lifespan underground. Similarly, in landscaping, ensuring proper drainage around wooden structures like fence posts or retaining walls can prevent premature rotting.

The takeaway is clear: managing moisture is key to controlling wood decay underground. By understanding the delicate balance between dampness and saturation, we can make informed decisions to either preserve or accelerate the natural process of decomposition.

Exploring Muir Woods: Average Visitor Time and Tips for Your Trip

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$15.31

Soil Type: Clay soils retain moisture, accelerating rot compared to sandy soils

Clay soils, with their fine particles and high density, act as a sponge, holding water long after it has stopped raining. This moisture retention is a double-edged sword for buried wood. While water is essential for the fungi and bacteria that decompose wood, excessive moisture can drown these organisms, slowing the rotting process. However, in clay soils, the balance often tips toward acceleration. The persistent dampness creates an ideal environment for rot-causing fungi, which thrive in consistently moist conditions. This means that wood buried in clay soil can decompose significantly faster than in other soil types, often within 5 to 10 years, depending on the wood species and other factors.

To illustrate, consider a scenario where two identical wooden posts are buried—one in clay soil and the other in sandy soil. The post in clay soil, surrounded by moisture-rich earth, will likely show signs of rot within a few years, while the one in sandy soil, which drains quickly, may remain intact for a decade or more. This comparison highlights the critical role soil type plays in wood decomposition. For homeowners or builders, this means that clay-heavy areas may require more durable materials or treatments for underground structures to prevent premature decay.

If you’re planning to bury wood in clay soil, take proactive steps to mitigate moisture’s effects. Elevate the wood slightly using gravel or sand to improve drainage, or treat the wood with preservatives like creosote or copper azole. These treatments create a barrier against fungi and insects, extending the wood’s lifespan even in wet conditions. Additionally, consider using naturally rot-resistant wood species like cedar or redwood, though even these will succumb more quickly in clay soils without proper precautions.

A cautionary note: while clay soils accelerate rot, they can also preserve wood under specific conditions. In anaerobic environments—where oxygen is scarce, such as in waterlogged clay—decomposition slows dramatically. This phenomenon is why ancient wooden artifacts are sometimes found remarkably intact in clay-rich riverbeds or bogs. However, for practical purposes, assume that buried wood in clay soil will rot faster unless measures are taken to control moisture. Understanding this dynamic allows for better decision-making in construction, landscaping, or even archaeological preservation efforts.

Understanding Wood Tick Burrowing: Timeframe and Prevention Tips

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$65.96 $70.81

Wood Type: Softwoods rot faster than hardwoods due to lower density

Softwoods, such as pine and spruce, decompose more rapidly underground compared to hardwoods like oak or teak, primarily due to their lower density. This characteristic allows moisture and microorganisms to penetrate softwoods more easily, accelerating the rotting process. For instance, untreated pine buried underground can begin to show signs of decay within 5–10 years, while oak might take 25–50 years to reach a similar state. Understanding this difference is crucial for applications like landscaping, fencing, or construction, where the longevity of buried wood is a key consideration.

The density of wood directly influences its resistance to decay. Softwoods have larger, less compact cells, making them more susceptible to water absorption and fungal invasion. In contrast, hardwoods possess denser, more complex cell structures that act as a natural barrier against moisture and pests. For practical purposes, if you’re burying wood in a humid environment, opting for hardwoods can significantly extend the material’s lifespan. However, if temporary support or quick decomposition is desired, softwoods are the more cost-effective choice.

To mitigate the rapid decay of softwoods, consider treating them with preservatives like creosote or copper azole before burial. These treatments can add 5–10 years to their lifespan, making them more comparable to untreated hardwoods in terms of durability. Another strategy is to bury softwoods in well-drained soil, as excessive moisture accelerates rot. For example, using gravel or sand as a base can improve drainage and slow decomposition, even for less dense woods.

Comparatively, hardwoods’ slower decay rate makes them ideal for long-term underground structures, such as fence posts or retaining walls. While they are more expensive upfront, their durability often justifies the investment. Softwoods, on the other hand, are better suited for temporary applications like garden borders or compost bins, where replacement every 5–10 years is feasible. By matching wood type to its intended use, you can balance cost, durability, and environmental impact effectively.

In summary, the choice between softwoods and hardwoods for underground use hinges on their density-driven decay rates. Softwoods decompose faster due to their porous structure, while hardwoods’ density offers greater resistance to rot. By applying preservatives, improving soil drainage, or selecting the appropriate wood type for the task, you can optimize both longevity and functionality. Whether prioritizing cost, durability, or environmental factors, understanding these differences ensures informed decision-making for any project involving buried wood.

Understanding the Ancient Process: How Long Does Petrified Wood Take?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$15.85 $16.99

Temperature Effects: Warmer climates increase bacterial activity, hastening decomposition

Warmer climates act as accelerants for wood decomposition underground, primarily due to their impact on bacterial activity. Bacteria, the primary decomposers of wood, thrive in temperatures between 77°F and 104°F (25°C and 40°C). In regions like the southeastern United States or tropical areas, where soil temperatures often fall within this range, bacterial metabolism spikes. This heightened activity breaks down cellulose and lignin—wood’s structural components—at a faster rate. For instance, a pine log buried in Florida’s humid, warm soil might decompose in 5–7 years, compared to 10–15 years in cooler, drier regions like the Pacific Northwest.

To harness this effect intentionally, such as in composting or land reclamation, ensure the buried wood is in soil with consistent warmth. Avoid burying wood in shaded areas or during colder seasons, as temperature fluctuations can slow decomposition. For optimal results, bury wood no deeper than 12 inches, where soil temperatures are more stable and warmer due to sunlight penetration. Adding nitrogen-rich materials like grass clippings can further fuel bacterial activity, reducing decomposition time by up to 30%.

However, warmer climates aren’t without drawbacks. Rapid decomposition can lead to quicker nutrient depletion in the surrounding soil, potentially harming nearby plants. To mitigate this, monitor soil pH and nutrient levels annually, and supplement with organic fertilizers if necessary. Additionally, in areas prone to pests like termites, warmer temperatures can exacerbate infestations, so consider treating wood with natural repellents like neem oil before burial.

Comparatively, cooler climates slow decomposition, preserving wood longer—a benefit for archaeological sites or historical preservation. Yet, for practical applications like land clearing or gardening, warmer climates offer a clear advantage. By understanding this temperature-bacteria relationship, you can predict decomposition timelines more accurately and manipulate conditions to achieve desired outcomes. For example, in a warm climate, a wooden fence post buried as part of soil enrichment will break down within 3–5 years, whereas in a cooler climate, it might persist for over a decade.

In summary, warmer climates significantly shorten wood decomposition times underground by boosting bacterial activity. To maximize this effect, bury wood in shallow, warm soil, add nitrogen-rich amendments, and monitor for pests and nutrient depletion. Whether clearing land or enriching soil, leveraging temperature effects ensures efficient, predictable results.

Aluminum Clad Wood Windows Lifespan: Durability and Longevity Explained

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Pest Influence: Termites and fungi significantly shorten wood’s lifespan underground

Wood buried underground faces a relentless assault from pests, particularly termites and fungi, which can drastically reduce its lifespan. Termites, often referred to as "silent destroyers," are voracious eaters of cellulose, the primary component of wood. A mature termite colony, consisting of thousands to millions of individuals, can consume up to one pound of wood per day. For a standard 2x4 wooden post, this means a colony could theoretically devour it in under a year, though environmental factors and wood treatment can slow this process. Fungi, on the other hand, thrive in damp, dark environments, breaking down wood through enzymatic action. Certain species, like *Serpula lacrymans* (dry rot fungus), can degrade wood at a rate of 1-2 millimeters per year, depending on moisture levels and temperature. Together, these pests create a dual threat that accelerates wood decay far beyond natural weathering processes.

To mitigate the impact of termites, preventive measures are essential. Treating wood with chemical preservatives like chromated copper arsenate (CCA) or borate-based solutions can deter termite infestations. For example, pressure-treated lumber, which is infused with preservatives, can last 20-40 years underground, compared to untreated wood, which may succumb to termites in as little as 2-5 years. Physical barriers, such as stainless steel mesh or sand layers, can also block termite access. However, these methods are not foolproof, and regular inspections are crucial, especially in termite-prone regions like the southeastern United States or Australia. For fungi, moisture control is key. Ensuring proper drainage and using water-resistant barriers can significantly slow fungal growth, extending wood’s underground lifespan by decades.

A comparative analysis reveals the stark difference in wood longevity based on pest exposure. In a controlled study, untreated pine stakes buried in a termite-infested area showed visible damage within six months, while those in a fungus-prone but termite-free zone remained relatively intact for over two years. This highlights the disproportionate impact of termites compared to fungi, though both are formidable adversaries. Interestingly, the presence of both pests in the same environment creates a synergistic effect, with termites creating entry points for fungal spores and fungi softening wood for easier termite consumption. This interplay underscores the importance of addressing both threats simultaneously.

For practical application, homeowners and builders should adopt a multi-pronged strategy. First, select wood species naturally resistant to decay, such as cedar or redwood, which contain tannins that repel pests. Second, apply protective coatings or treatments to all wood surfaces, paying special attention to cut ends and joints where pests often gain entry. Third, monitor environmental conditions, avoiding areas with high moisture or known pest activity. For example, burying wood in well-drained soil with a slight slope can reduce fungal risk, while installing termite bait stations around the perimeter provides early detection and control. By combining these measures, wood can survive underground for 10-30 years or more, even in challenging conditions.

In conclusion, while wood’s underground lifespan is inherently limited, termites and fungi act as catalysts for rapid decay, often reducing it to a fraction of its potential durability. Understanding their behaviors and implementing targeted strategies can significantly extend wood’s usefulness in subterranean applications. Whether for fence posts, landscaping, or structural supports, proactive pest management is not just beneficial—it’s essential for long-term success.

Durability of Wooden Groynes: Lifespan and Coastal Protection Insights

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The time it takes for wood to rot underground varies depending on factors like wood type, soil moisture, temperature, and oxygen levels, but it typically ranges from 5 to 50 years.

Yes, hardwoods like oak or cedar rot more slowly (10–50 years) due to natural preservatives, while softwoods like pine decompose faster (5–15 years).

Burying wood deeper can reduce oxygen exposure, slowing decay in aerobic conditions, but anaerobic bacteria can still cause rotting, though at a slower pace.

Pressure-treated wood lasts longer underground (10–30 years) due to chemical preservatives, but it will eventually rot depending on soil conditions and treatment quality.

Yes, moist, acidic soils accelerate rotting, while dry, alkaline soils slow it down. Sandy soils drain faster, reducing decay, while clay soils retain moisture, speeding it up.

![Preservation [Import]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/81+IBpvrysL._AC_UL320_.jpg)