Petrification is a fascinating geological process that transforms organic wood into stone over millions of years. It begins when wood becomes buried under sediment, shielding it from decay and oxygen. Groundwater rich in minerals like silica, calcite, or pyrite then seeps into the wood’s cellular structure, gradually replacing the organic material with mineral deposits. This slow mineralization preserves the wood’s original structure, often retaining intricate details like growth rings and grain patterns. The duration of petrification varies widely, typically ranging from 5 million to 20 million years, depending on factors such as mineral availability, temperature, and pressure. The result is a fossilized wood, known as petrified wood, that is incredibly durable and offers a unique glimpse into Earth’s ancient past.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Process Time | Typically takes millions of years (e.g., 1-10 million years or more) |

| Key Factors |

|

| Mineral Composition | Primarily silica (quartz); occasionally calcite, pyrite, or other minerals |

| Preservation Level | Cellular structure often preserved in detail |

| Appearance | Retains original wood texture but becomes stone-like, often with fossilized color variations |

| Examples | Petrified Forest National Park (Arizona, USA) – wood petrified over 225 million years |

| Variability | Timeframe depends on mineral availability, temperature, pressure, and burial depth |

| Human Acceleration | Laboratory petrification can be achieved in months to years under controlled conditions |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Factors affecting petrification speed

Petrification, the process by which wood transforms into stone, is not a swift event but a geological marathon. The speed at which this occurs depends on a delicate interplay of environmental factors, each contributing uniquely to the timeline. Understanding these factors can demystify why some petrified wood forms in thousands of years while others take millions.

Mineral Availability and Composition: The presence of silica-rich groundwater is critical, as silica is the primary mineral replacing organic material. Areas with volcanic activity or sedimentary basins rich in quartz and calcite accelerate petrification. For instance, the rapid burial of wood in ash layers from volcanic eruptions provides an ideal environment, as seen in the famous Yellowstone petrified forests. In contrast, wood in arid regions with limited mineral-rich water may take significantly longer to petrify, if at all.

Temperature and Pressure: Higher temperatures increase the rate of chemical reactions, expediting mineralization. Wood buried deep within the Earth, where geothermal heat is present, petrifies faster than that near the surface. Pressure, too, plays a role by compacting the wood and forcing minerals into its cellular structure. Subsurface environments, such as those found in riverbeds or deltas, offer optimal conditions for both temperature and pressure, reducing petrification time from millions to potentially thousands of years.

PH Levels and Water Flow: The acidity or alkalinity of the surrounding environment influences mineral dissolution and precipitation. Neutral to slightly alkaline conditions (pH 7-8.5) are ideal, as they promote silica solubility and its subsequent infiltration into wood cells. Stagnant water, while necessary for mineral transport, can lead to uneven petrification if it lacks consistent flow. Dynamic water systems, like those in river channels, ensure a steady supply of mineral-rich water, fostering uniform and faster petrification.

Organic Material Preservation: The initial preservation of wood from decay is a prerequisite for petrification. Rapid burial under sediment or volcanic ash shields wood from oxygen and microorganisms, slowing decomposition. Without this protective layer, wood disintegrates before mineralization can occur. For example, wood submerged in peat bogs, where anaerobic conditions prevail, can survive long enough for petrification to begin, though the process remains slow due to limited mineral availability.

Time and Patience: Despite optimal conditions, petrification is inherently a test of time. Even under ideal circumstances, the transformation from wood to stone requires millennia. Human timescales pale in comparison to geological ones, making petrified wood a rare and valuable relic of Earth’s history. Accelerating this process artificially is nearly impossible, as it relies on natural forces beyond human control. Thus, the speed of petrification remains a testament to nature’s patience and precision.

Clearcoat Drying Time on Wood: Factors Affecting Cure and Finish

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Role of mineral content in wood

Wood petrification is a process where organic matter transforms into stone, and the mineral content within the wood plays a pivotal role in this transformation. The presence of minerals like silica, calcite, and pyrite determines the rate and quality of petrification. Silica, for instance, is the most common mineral involved, infiltrating the wood’s cellular structure and gradually replacing organic material with quartz. This mineralization process preserves intricate details, such as growth rings and cellular patterns, creating fossilized wood that can last millions of years. Without sufficient mineral content, wood is more likely to decay rather than petrify, underscoring the critical role minerals play in this natural phenomenon.

To understand the role of mineral content, consider the environment in which wood petrifies. Petrification typically occurs in areas rich in mineral-laden water, such as volcanic ash deposits or sedimentary basins. When wood is buried in these environments, groundwater saturated with dissolved minerals seeps into the wood, filling its pores and cavities. Over time, these minerals precipitate out of the water, crystallizing within the wood’s structure. The concentration of minerals in the surrounding sediment directly influences the speed and completeness of petrification. For example, wood buried in silica-rich environments may petrify within 1,000 to 10,000 years, while wood in less mineral-rich areas may take significantly longer or not petrify at all.

Practical considerations for those interested in petrification include replicating these mineral-rich conditions. If you’re attempting to petrify wood artificially, ensure the wood is submerged in a solution with a high silica concentration, typically around 5-10% by weight. This can be achieved using sodium silicate or other silica compounds. Maintain a pH level between 7 and 9 to encourage mineral precipitation, and keep the wood in a sealed environment to prevent evaporation. Regularly monitor the solution’s mineral content and replenish it as needed to ensure consistent mineralization. This method, while time-consuming, can produce petrified wood in a matter of months to years, compared to the millennia required in nature.

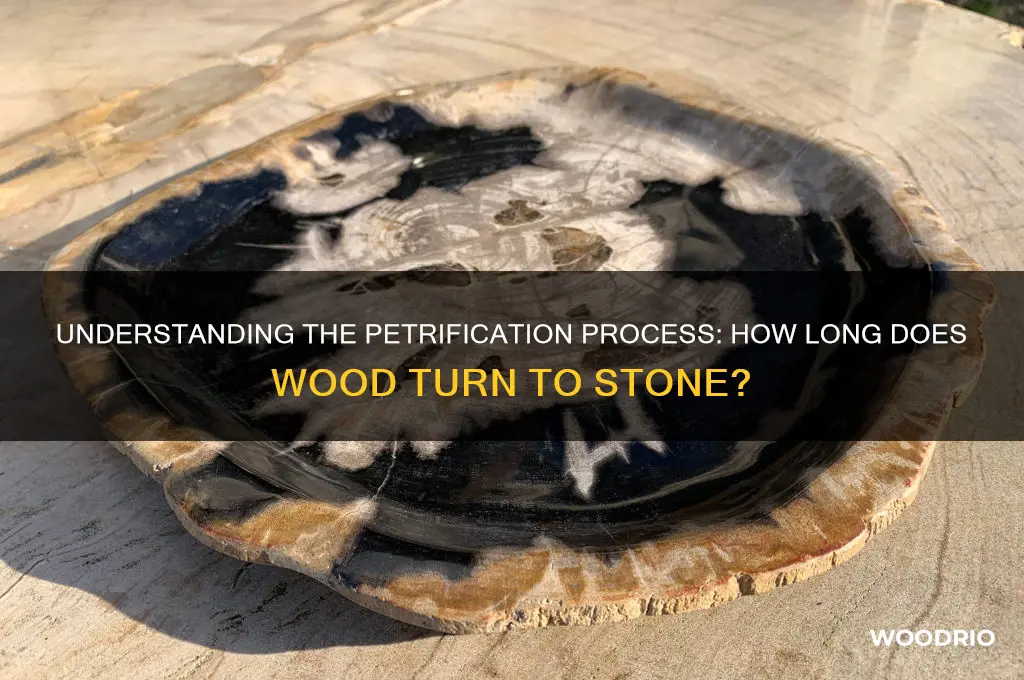

Comparatively, the mineral content also affects the aesthetic and structural qualities of petrified wood. Wood petrified with silica tends to retain its original color and texture, often displaying vibrant hues of red, yellow, and brown due to trace impurities like iron oxide. In contrast, wood petrified with calcite may appear more opaque and white. The choice of mineral can thus be tailored to the desired outcome, whether for scientific study or decorative purposes. For collectors or artisans, understanding these mineral-specific outcomes allows for better selection and treatment of petrified wood specimens.

In conclusion, the mineral content in wood is not just a factor but the driving force behind petrification. From the natural processes occurring in mineral-rich environments to artificial methods mimicking these conditions, minerals dictate the timeline, quality, and characteristics of petrified wood. By focusing on the role of minerals, one gains both a scientific understanding and practical tools to engage with this fascinating transformation. Whether for research, art, or curiosity, the interplay between wood and minerals offers a window into Earth’s geological history and creative possibilities.

Wood Frog's Vernal Pool Stay: Duration and Survival Insights

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Impact of environmental conditions

Wood petrification is a process heavily influenced by the surrounding environmental conditions, which dictate the speed and likelihood of transformation. High silica content in the environment, often found in volcanic or sedimentary settings, accelerates petrification by providing the necessary minerals for cell-by-cell replacement. For instance, wood buried in silica-rich hot springs can petrify within 1,000 to 10,000 years, compared to millions of years in less mineralized environments. This highlights the critical role of mineral availability in determining the timeline of petrification.

Temperature and pH levels also play a pivotal role in the petrification process. Optimal conditions for petrification occur in environments with temperatures between 25°C and 50°C, where chemical reactions proceed at a steady pace. Acidic environments (pH below 5) can dissolve wood before petrification occurs, while alkaline conditions (pH above 8) may slow mineral deposition. For example, wood submerged in neutral to slightly alkaline groundwater with a pH of 7 to 8.5 is more likely to petrify successfully. Monitoring and controlling these factors in artificial petrification experiments can reduce the process from millennia to decades.

The presence of oxygen and water is another environmental factor that significantly impacts petrification. Anaerobic conditions, such as those found in deep sediment layers, slow decay but also hinder mineral infiltration, prolonging the process. Conversely, well-oxygenated environments promote rapid decay, often preventing petrification altogether. Wood buried in waterlogged environments, like riverbeds or swamps, has a higher chance of petrifying due to the constant flow of mineral-rich water. Practical tip: For experimental petrification, submerge wood in a solution of silica-rich water with controlled oxygen levels to mimic these conditions.

Comparing natural and artificial environments reveals the stark difference in petrification timelines. In nature, the process often takes millions of years due to fluctuating conditions and limited mineral availability. In contrast, laboratory settings can reduce this timeline to 5–20 years by optimizing factors like silica concentration, temperature, and pH. For instance, using a 20% silica solution at 40°C and a pH of 8 can achieve petrification in under a decade. This comparison underscores the importance of environmental control in accelerating the process for practical or artistic purposes.

Finally, the geological setting of the environment determines the type of minerals deposited during petrification, influencing the final appearance and durability of the petrified wood. For example, wood petrified in iron-rich environments may exhibit reddish hues, while manganese deposits create pink or black tones. Practical takeaway: When selecting a location for natural petrification or sourcing materials for artificial processes, consider the mineral composition of the surrounding soil or water to achieve desired aesthetic outcomes. Understanding these environmental nuances allows for both preservation and creative manipulation of the petrification process.

Durability of Outdoor Wood Boilers: Lifespan and Maintenance Tips

You may want to see also

Differences in wood type and density

Wood petrification is a process heavily influenced by the type and density of the wood itself. Softwoods, like pine or spruce, tend to have larger cell structures and lower density, making them more susceptible to decay before mineralization can occur. This means softwoods often require more specific conditions—such as rapid burial in sediment-rich environments—to petrify successfully. In contrast, hardwoods like oak or teak, with their denser cell walls and higher lignin content, are more resistant to decay and thus have a better chance of surviving long enough to petrify, even in less ideal conditions.

Consider the practical implications of wood density in petrification. Denser woods, such as ebony or ironwood, have a natural advantage due to their compact cellular structure, which slows water infiltration and microbial activity. This density not only prolongs the wood’s lifespan but also allows minerals like silica or calcite to penetrate more uniformly, resulting in a more detailed fossilization. For example, a dense hardwood buried in a mineral-rich riverbed might fully petrify within 10,000 to 20,000 years, while a softer wood under the same conditions could take significantly longer or fail entirely.

To maximize the chances of wood petrification, start by selecting dense hardwoods with low resin content, as resins can hinder mineral infiltration. Bury the wood in an environment rich in dissolved minerals, such as near hot springs or volcanic ash deposits. Ensure the burial site is anaerobic to minimize decay. For experimental purposes, simulate these conditions by submerging wood in a solution of silica or calcium carbonate at a concentration of 10–20% and maintaining a pH of 7–8. Monitor the process over months or years, noting changes in weight and texture as minerals replace organic material.

The takeaway is clear: wood type and density are not just passive factors but active determinants of petrification success. Softwoods, despite their beauty, are less likely to fossilize without extraordinary preservation conditions. Hardwoods, particularly dense varieties, offer the best prospects for petrification, especially when paired with mineral-rich environments. By understanding these differences, enthusiasts and researchers can strategically select and prepare wood samples to increase the likelihood of successful petrification, turning organic matter into enduring stone.

Hollywood Studios Ticket Window Wait Times: What to Expect

You may want to see also

Typical timeframes for petrification process

Petrification, the process by which wood transforms into stone, is a geological marvel that unfolds over vast timescales. Unlike quick preservation methods like freezing or drying, petrification requires millions of years, making it a testament to Earth’s patience. The typical timeframe for this process ranges from 5 to 50 million years, depending on environmental conditions. For instance, wood buried in sediment-rich, mineral-laden waters—such as ancient swamps or volcanic ash deposits—tends to petrify faster than wood in drier, less mineralized environments. This duration highlights the rarity and value of petrified wood, which is essentially a fossilized snapshot of prehistoric forests.

To understand why petrification takes so long, consider the steps involved. First, the wood must be buried quickly to prevent decay. Next, groundwater rich in minerals like silica, calcite, or pyrite seeps into the wood, replacing its organic cells with these minerals in a process called permineralization. This cellular-level transformation is painstakingly slow, occurring at a rate of millimeters per thousand years. For example, a small log might take 10 million years to fully petrify, while larger tree trunks could require closer to 50 million years. The key takeaway is that petrification is not just a process of preservation but a complete metamorphosis, turning organic matter into a durable, stone-like replica.

While the average timeframe for petrification is millions of years, exceptions exist. In rare cases, accelerated petrification can occur in environments with extremely high mineral concentrations, such as geothermal hot springs or areas near mineral-rich volcanic activity. These conditions can reduce the process to a mere few thousand years, though such instances are uncommon. Conversely, wood in less ideal conditions—like shallow, oxygen-rich soils—may never petrify at all, instead decomposing entirely. This variability underscores the importance of specific geological and chemical factors in determining how long petrification takes.

Practical tips for observing petrification in action are limited, given the process’s timescale, but visiting sites like the Petrified Forest National Park in Arizona offers a glimpse into its results. Here, 225-million-year-old logs have been preserved in stunning detail, their original structures transformed into quartz-rich stone. For those interested in smaller-scale experiments, modern techniques like silica gel immersion can mimic petrification over months or years, though these methods produce artificial results rather than true fossils. Ultimately, the natural petrification process remains a phenomenon best appreciated through its ancient, enduring outcomes.

Durability of Red Wood Playsets: Lifespan and Maintenance Tips

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The process of wood petrification typically takes thousands to millions of years, depending on environmental conditions such as mineral-rich water, consistent pressure, and stable temperatures.

Factors like the presence of silica-rich water, burial depth, temperature, and the type of wood can influence how quickly petrification occurs. Faster processes may take a few thousand years, while slower ones can extend to millions of years.

Yes, wood can petrify faster in environments with high mineral concentrations, such as volcanic ash or geothermal areas, where silica and other minerals are readily available to replace organic material. However, even in optimal conditions, it still takes centuries to millennia.