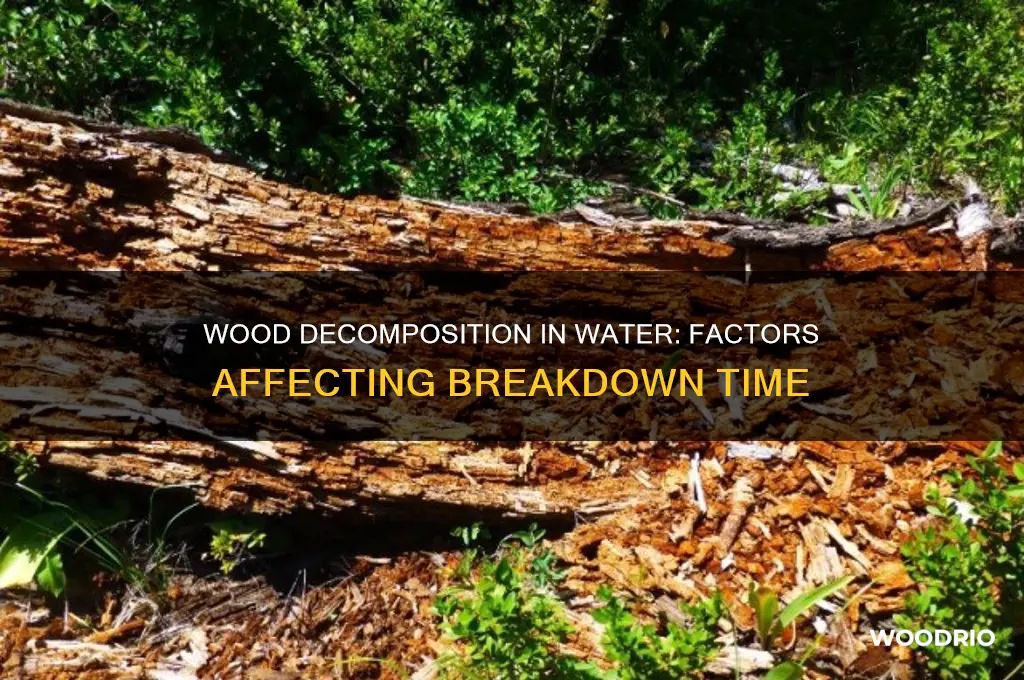

Wood decomposition in water is a complex process influenced by factors such as wood type, water conditions, and environmental factors. Generally, hardwoods like oak can take 1-3 years to decompose in water, while softer woods like pine may break down in 6 months to 2 years. However, submerged wood in stagnant, oxygen-depleted water can persist for decades due to slowed microbial activity, whereas wood in flowing, oxygen-rich water decomposes faster. Temperature, pH, and the presence of organisms like fungi and bacteria also play significant roles in determining decomposition rates. Understanding these variables is crucial for assessing wood's environmental impact and its role in aquatic ecosystems.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Factors Affecting Decomposition Rate

Wood submerged in water can decompose at vastly different rates depending on several key factors. Temperature plays a critical role, with warmer waters accelerating microbial activity and enzymatic processes that break down cellulose and lignin. For instance, wood in tropical waters may degrade within 5–10 years, while in colder temperate or polar regions, this process can stretch to 50 years or more. Understanding this temperature-driven variability is essential for predicting decomposition timelines in different aquatic environments.

The type of wood significantly influences its durability underwater. Hardwoods like oak or teak, rich in lignin and natural resins, resist decay longer than softwoods like pine or cedar. For example, oak pilings in marine environments can last 30–50 years, whereas pine might degrade in half that time. This difference highlights the importance of wood selection in aquatic construction or ecological projects.

Water salinity and oxygen levels create contrasting environments for decomposition. In saltwater, wood often lasts longer due to the preservative effect of salt, which deters many wood-degrading fungi and bacteria. Freshwater, however, typically fosters faster decay because it supports a broader range of microbial life. Anaerobic conditions (low oxygen) in stagnant water can slow decomposition by limiting aerobic bacteria, but they may promote the activity of anaerobic organisms that break down wood differently.

Physical factors like water flow and sedimentation also impact decomposition. Strong currents increase abrasion and fragmentation, speeding up the breakdown of wood into smaller, more degradable pieces. Conversely, sediment buildup can bury wood, reducing exposure to decomposers and slowing decay. For instance, a log in a fast-moving river might disintegrate within 2–5 years, while one buried in a calm lake could persist for decades.

Human interventions, such as chemical treatments or structural design, can alter decomposition rates. Creosote-treated wooden structures, commonly used in marine environments, can last 40–60 years due to the preservative’s toxicity to microbes. Similarly, designing wooden components to minimize water absorption or using composite materials can extend their lifespan. These strategies are particularly valuable in engineering applications where longevity is critical.

Durability of Wood Raised Beds: Lifespan and Maintenance Tips

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Type of Wood and Durability

Wood decomposition in water is a race against time, with the type of wood serving as the starting pistol. Dense, resinous woods like cedar and redwood boast natural preservatives, allowing them to withstand aquatic environments for decades, even centuries. Their secret lies in their chemical composition: high levels of tannins and oils repel fungi and insects, the primary culprits behind wood decay. Imagine a cedar dock, its surface weathered but structurally sound after 30 years of constant water exposure—a testament to the power of inherent durability.

Contrast this with softwoods like pine or spruce, which decompose at a far quicker pace. Their lower density and lack of natural preservatives make them susceptible to water absorption, swelling, and cracking. Within 5 to 10 years, a pine fence post submerged in water might show significant signs of rot, its fibers crumbling under the relentless attack of moisture-loving microorganisms. This vulnerability underscores the importance of matching wood type to its intended aquatic application.

For those seeking middle ground, hardwoods like oak and teak offer a compromise. While not as resilient as cedar, their dense grain structure and moderate natural oils provide respectable durability in water. A teak boat hull, for instance, can endure 50 years or more with proper maintenance, its golden patina deepening as it ages gracefully against the elements. However, even these hardy woods require vigilance—regular sealing and inspection are essential to prolong their lifespan.

Practical tip: When selecting wood for water-exposed projects, consider not only the type but also the treatment options. Pressure-treated lumber, infused with preservatives like chromated copper arsenate (CCA), can significantly extend the life of less durable woods. For example, pressure-treated pine can last 20–40 years in water, rivaling the longevity of some hardwoods at a fraction of the cost. Yet, environmental concerns surrounding CCA’s toxicity necessitate careful handling and disposal, highlighting the trade-offs in durability enhancement.

In conclusion, the durability of wood in water is a nuanced interplay of species, treatment, and maintenance. By understanding these factors, one can make informed choices that balance longevity, cost, and environmental impact. Whether crafting a waterfront deck or a submerged pier, the right wood selection ensures that your project stands—or floats—the test of time.

Composting Wood Chips: Understanding the Timeframe for Natural Breakdown

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Water Conditions and Impact

Wood submerged in water decomposes at vastly different rates depending on the aquatic environment. In stagnant, oxygen-depleted water like ponds or marshes, anaerobic bacteria dominate, breaking down wood slowly over 10 to 50 years. Conversely, flowing rivers with oxygen-rich currents accelerate decay, reducing this timeframe to 2 to 10 years as aerobic microorganisms thrive. Salinity also plays a critical role: saltwater environments inhibit decomposition due to osmotic stress on bacteria, often preserving wood for decades to centuries, as seen in shipwrecks. Freshwater, with its neutral pH and balanced mineral content, typically falls between these extremes, averaging 5 to 15 years for complete breakdown.

To maximize wood preservation in water, consider these practical steps. First, choose a location with low oxygen levels, such as deep, still water bodies, to slow bacterial activity. Second, treat the wood with creosote or copper-based preservatives, which are toxic to microorganisms. Third, bury the wood under sediment to shield it from light and aerobic bacteria, a technique historically used in underwater construction. For those seeking to accelerate decomposition, place wood in warm, flowing water with temperatures above 20°C (68°F), as heat and turbulence enhance microbial activity.

The impact of water conditions on wood decomposition extends beyond timeframes, influencing ecological systems. In nutrient-rich waters, decaying wood becomes a hotspot for invertebrates and fungi, fostering biodiversity. However, in polluted environments, toxins absorbed by the wood can leach into the water during decomposition, harming aquatic life. For instance, creosote-treated pilings release polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), which are carcinogenic to fish and humans. Thus, understanding water conditions is crucial not only for predicting decay rates but also for mitigating environmental risks.

Comparing freshwater and saltwater environments reveals stark contrasts in wood preservation. While saltwater’s salinity preserves wood by dehydrating cells and deterring bacteria, freshwater’s neutrality allows for steady, predictable decay. For example, oak barrels submerged in freshwater lakes decompose within 5 to 10 years, whereas those in the ocean can remain intact for 50 to 100 years. This comparison highlights the importance of water chemistry in material longevity, offering insights for industries like marine construction and archaeology.

Finally, climate change is altering water conditions, indirectly affecting wood decomposition rates. Rising temperatures increase microbial activity, shortening decay times in both freshwater and marine environments. Simultaneously, ocean acidification weakens wood’s structural integrity, making it more susceptible to breakdown despite saltwater’s preservative effects. These shifts underscore the dynamic relationship between water conditions and wood decay, emphasizing the need for adaptive strategies in managing aquatic structures and ecosystems.

Durability of Wood Frame Homes: Lifespan and Maintenance Tips

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Microbial Activity in Water

Wood submerged in water doesn't vanish overnight. Its decomposition timeline hinges on a microscopic army: aquatic microorganisms. These bacteria, fungi, and other microbes are the primary decomposers, breaking down complex wood compounds into simpler substances. Their activity is a delicate dance influenced by water's unique environment.

Unlike terrestrial decomposition, where oxygen is abundant, aquatic microbes often face oxygen-depleted conditions. This shifts the decomposition process towards anaerobic pathways, which are generally slower. Imagine a log sinking into a murky pond versus one resting on a sunny, oxygen-rich stream bed – the latter will likely decompose faster due to the increased microbial activity fueled by oxygen.

Temperature plays a crucial role in this microbial ballet. Warmer water accelerates metabolic rates, speeding up decomposition. In tropical waters, a wooden structure might crumble within a decade, while in colder climates, it could persist for centuries. Think of the preserved Viking ships unearthed in Scandinavian fjords, testament to the slowing effect of cold water on microbial activity.

Salinity also throws a wrench into the works. Saltwater is harsher on most wood-decomposing microbes, leading to slower breakdown compared to freshwater environments. This is why shipwrecks in the ocean often retain their wooden structures longer than those in rivers or lakes.

Understanding these microbial dynamics is crucial for various applications. Archaeologists rely on this knowledge to interpret underwater archaeological sites, while engineers factor in decomposition rates when designing wooden structures for aquatic environments. By manipulating factors like oxygen levels, temperature, and salinity, we can even control the rate of wood decomposition in water, potentially extending the lifespan of wooden structures or accelerating the breakdown of unwanted debris.

Yellowjackets' Survival: Unraveling the Length of Their Harrowing Woods Ordeal

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Comparison to Land Decomposition

Wood submerged in water decomposes at a markedly different rate compared to wood on land, primarily due to the absence of oxygen in aquatic environments. While land decomposition relies on aerobic microorganisms that thrive in oxygen-rich soil, waterlogged wood undergoes anaerobic decomposition, a slower process driven by bacteria and fungi adapted to low-oxygen conditions. This fundamental difference in microbial activity means submerged wood can persist for decades, even centuries, whereas wood on land typically breaks down within 10 to 50 years, depending on factors like climate, wood type, and exposure to insects.

Consider the practical implications for environmental management. In aquatic ecosystems, sunken logs can serve as long-term habitats for aquatic organisms, contributing to biodiversity. However, in land settings, decomposing wood rapidly returns nutrients to the soil, fueling plant growth. For instance, a pine log in a temperate forest might decompose within 20 years, enriching the soil with organic matter, while a similar log submerged in a lake could remain structurally intact for over 100 years, acting as a substrate for algae and invertebrates. This contrast highlights the need to tailor conservation strategies to the specific decomposition dynamics of each environment.

To illustrate further, compare the fate of wooden structures in different settings. A wooden bridge collapsed into a river may retain its structural integrity for generations, posing navigational hazards or becoming an artificial reef. Conversely, a wooden fence post buried in soil will gradually disintegrate, necessitating periodic replacement. This disparity underscores the importance of material selection and placement in construction projects. For aquatic applications, consider using treated wood or alternative materials to mitigate long-term environmental impacts, while on land, embrace the natural decomposition process as part of sustainable land management.

Finally, understanding these decomposition differences has direct applications in archaeology and historical preservation. Shipwrecks with wooden components often remain remarkably preserved in underwater environments, offering invaluable insights into maritime history. In contrast, wooden artifacts buried on land are more prone to rapid deterioration, requiring urgent excavation and conservation efforts. By recognizing how water and land environments uniquely influence wood decay, researchers and conservationists can better prioritize resources and techniques to protect cultural heritage.

How Long Blood Stains Last in Wood: A Comprehensive Guide

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Wood decomposition in water varies, but it generally takes 10 to 50 years, depending on factors like wood type, water conditions, and microbial activity.

Yes, hardwoods like oak decompose more slowly (25–50 years), while softwoods like pine decompose faster (10–25 years) due to differences in density and lignin content.

Yes, warmer water accelerates decomposition by increasing microbial activity, while colder water slows it down, prolonging the process.

Submerged wood often decomposes faster due to increased exposure to waterborne microorganisms and reduced oxygen, which promotes anaerobic breakdown.