Wood decomposition underground is influenced by several factors, including the type of wood, moisture levels, soil composition, and the presence of microorganisms. Hardwoods like oak and hickory typically take longer to rot, often requiring 10 to 50 years, while softer woods like pine decompose more quickly, usually within 5 to 15 years. Moist, acidic, or oxygen-poor environments accelerate decay, as they foster fungal and bacterial activity, whereas dry, alkaline, or well-drained soils slow the process. Understanding these variables is crucial for applications like landscaping, construction, or environmental conservation, where the longevity of buried wood plays a significant role.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Type of Wood | Hardwoods (e.g., oak, teak) last longer than softwoods (e.g., pine). |

| Moisture Content | Higher moisture accelerates decay; dry conditions slow it down. |

| Soil Type | Wet, acidic soils speed up rot; well-drained, alkaline soils slow it. |

| Oxygen Availability | Anaerobic conditions (lack of oxygen) slow decay. |

| Temperature | Warmer temperatures accelerate decomposition. |

| Microbial Activity | Presence of fungi and bacteria speeds up rotting. |

| Wood Treatment | Treated wood (e.g., pressure-treated) lasts significantly longer. |

| Burial Depth | Deeper burial can reduce oxygen and slow decay. |

| Average Rot Time (Untreated) | 5–10 years for softwoods; 20–50+ years for hardwoods. |

| Average Rot Time (Treated Wood) | 40+ years, depending on treatment type. |

| Environmental Factors | Climate, soil pH, and insect activity influence decay rate. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Moisture Levels: High moisture speeds up wood decay underground due to fungal growth

- Wood Type: Softwoods rot faster than hardwoods due to lower density and resins

- Soil Conditions: Acidic soil accelerates rot; alkaline soil slows decomposition processes

- Temperature Impact: Warmer temperatures increase microbial activity, hastening wood breakdown

- Oxygen Exposure: Limited oxygen in soil promotes anaerobic bacteria, slowing rot

Moisture Levels: High moisture speeds up wood decay underground due to fungal growth

Wood buried underground doesn't simply vanish overnight. The timeline for its decomposition is a complex dance influenced heavily by moisture levels. While complete rot can take decades in arid conditions, high moisture acts as a catalyst, accelerating the process dramatically. This is due to the proliferation of fungi, nature's primary wood decomposers.

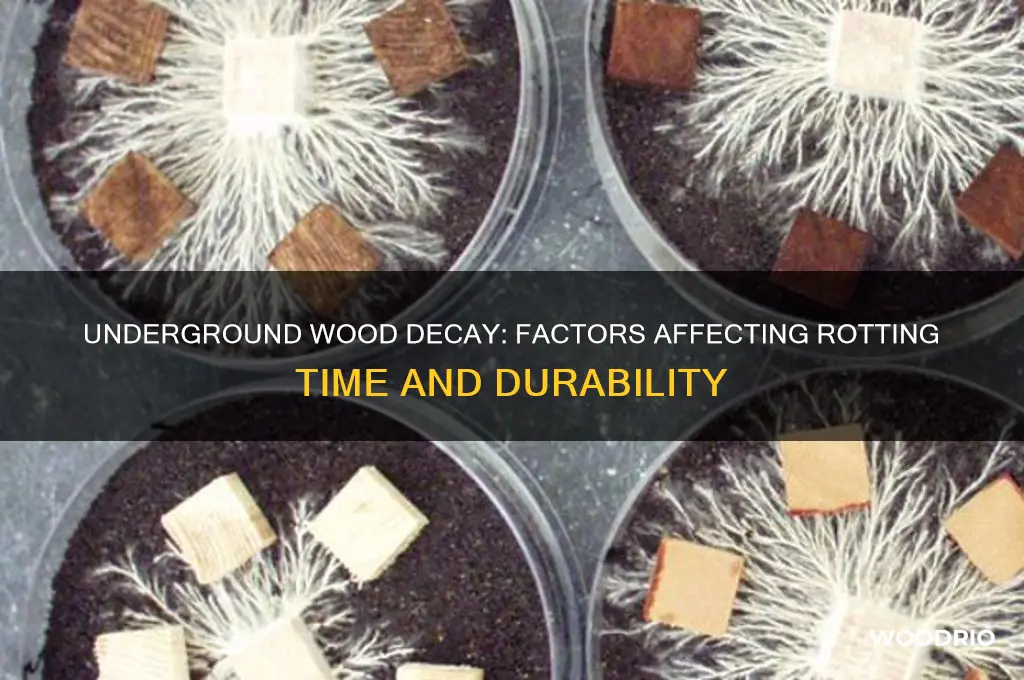

Fungal spores are ubiquitous in soil, lying dormant until conditions are favorable. Moisture provides the necessary environment for these spores to germinate and grow. As fungal hyphae penetrate the wood, they secrete enzymes that break down its complex cellulose and lignin structures. This process, known as white rot and brown rot, effectively digests the wood from within.

Imagine a scenario: two identical wooden posts, one buried in a dry, sandy soil, the other in a perpetually damp, clay-rich environment. The dry post, shielded from excessive moisture, might remain structurally sound for 20 years or more. Its counterpart, constantly bathed in moisture, could succumb to fungal attack within 5-10 years, depending on other factors like wood type and soil pH.

This highlights the critical role of moisture management in controlling wood decay. For applications requiring longevity, such as fence posts or foundation supports, strategies to minimize moisture contact are essential. This could involve using pressure-treated wood, applying water-repellent coatings, or ensuring proper drainage to prevent water pooling around the wood.

It's important to note that while high moisture accelerates decay, complete saturation can sometimes have the opposite effect. In waterlogged conditions, oxygen availability decreases, hindering fungal growth. This anaerobic environment can slow decomposition, though it often leads to other issues like warping and cracking due to constant wetting and drying cycles.

How Long Does Vinegar Smell Linger on Wood Surfaces?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$15.31

Wood Type: Softwoods rot faster than hardwoods due to lower density and resins

Softwoods, such as pine and spruce, decompose more rapidly underground compared to hardwoods like oak or maple. This disparity stems from their lower density and the presence of resins, which offer less resistance to decay. When buried, softwoods provide an ideal environment for fungi and bacteria to thrive, accelerating the rotting process. For instance, untreated pine can disintegrate within 5–10 years underground, while oak might persist for 25–50 years or more. Understanding this difference is crucial for applications like fencing, landscaping, or construction, where longevity is a key consideration.

The lower density of softwoods allows moisture to penetrate more easily, creating a damp environment that fungi and bacteria require to break down cellulose and lignin. Hardwoods, with their tighter grain structure, resist moisture absorption, slowing decay. Additionally, softwoods contain fewer natural preservatives like tannins, which are abundant in hardwoods and act as deterrents to decay. For practical purposes, if you’re burying wood for temporary use, softwoods are cost-effective and readily available. However, for long-term projects, investing in hardwoods or treated softwoods can save time and resources in the long run.

Resins in softwoods, while providing some natural protection against insects, do little to prevent fungal decay underground. In fact, once moisture breaches the resin barrier, decay accelerates rapidly. This is why softwoods are often treated with chemical preservatives like creosote or copper azole to extend their lifespan. If you’re working with softwoods, ensure they are properly treated or consider using them in above-ground applications where they’re less exposed to constant moisture. For underground use, hardwoods or treated alternatives are more reliable.

Comparatively, hardwoods’ denser structure and higher tannin content make them more resistant to rot, even without treatment. For example, black locust, a dense hardwood, can last over 40 years underground. If you’re unsure which wood to choose, assess the project’s lifespan and environmental exposure. Softwoods are ideal for short-term, low-moisture applications, while hardwoods excel in long-term, high-moisture scenarios. Always consider the trade-off between initial cost and long-term durability when selecting wood for underground use.

In summary, the choice between softwoods and hardwoods for underground use hinges on their density and natural resins. Softwoods decompose faster due to their porous structure and lower resistance to decay, making them suitable for temporary projects. Hardwoods, with their denser grain and natural preservatives, offer significantly longer lifespans, ideal for permanent installations. By understanding these differences, you can make informed decisions that balance cost, durability, and environmental conditions.

Veneer Wood Durability: Lifespan, Maintenance, and Longevity Explained

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$65.96 $70.81

Soil Conditions: Acidic soil accelerates rot; alkaline soil slows decomposition processes

Wood buried underground doesn't decompose at a fixed rate. Soil conditions play a critical role, with pH levels acting as a key determinant. Acidic soil, with a pH below 7, creates an environment conducive to faster wood rot. This is because the acidity promotes the growth of fungi and bacteria that break down cellulose, the primary component of wood. In contrast, alkaline soil, with a pH above 7, hinders these microorganisms, slowing the decomposition process significantly.

Understanding this relationship allows for strategic decisions when disposing of wood or planning projects involving buried wooden structures.

Imagine two identical wooden posts, one buried in acidic soil near a pine forest, the other in alkaline soil in a limestone-rich area. The post in acidic soil, benefiting from a pH range of 4.5 to 5.5, will likely show signs of decay within 5-10 years, while its alkaline counterpart, in soil with a pH of 7.5 or higher, might remain largely intact for decades. This example highlights the dramatic impact of soil pH on wood's longevity underground.

For those seeking to preserve wooden structures, choosing alkaline soil or amending acidic soil with lime can significantly extend their lifespan. Conversely, for composting or natural erosion control, acidic soil accelerates the process, allowing wood to return to the ecosystem more rapidly.

While pH is a major factor, it's not the sole determinant of wood rot. Moisture content, oxygen availability, and the presence of specific decomposing organisms also play crucial roles. However, understanding the pH effect allows for targeted interventions. For instance, in acidic soil prone to waterlogging, improving drainage can mitigate excessive moisture, slowing rot even in a naturally acidic environment. Conversely, in alkaline soil where decomposition is slow, introducing specific fungi species adapted to higher pH levels can accelerate the breakdown of wood for composting purposes.

By considering both the inherent pH of the soil and these additional factors, we can more accurately predict wood's decomposition rate and make informed choices for various applications.

Durability of Wood Frame Homes: Lifespan and Maintenance Tips

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$15.85 $16.99

Temperature Impact: Warmer temperatures increase microbial activity, hastening wood breakdown

Warmer temperatures act as a catalyst for microbial activity, significantly accelerating the decomposition of wood buried underground. Microorganisms such as bacteria and fungi thrive in environments where temperatures range between 70°F and 90°F (21°C to 32°C), their metabolic rates doubling for every 18°F (10°C) increase within this range. This heightened activity means that wood in warmer climates or seasons can decompose up to 50% faster than in cooler conditions. For instance, a wooden post buried in a temperate forest might take 10–15 years to fully rot, while the same post in a tropical region could disintegrate in as little as 5–7 years.

To mitigate this effect, consider burying wood in cooler, shaded areas or during colder seasons if preservation is a goal. For practical applications like fencing or landscaping, using pressure-treated wood or natural rot-resistant species (e.g., cedar or redwood) can counteract the accelerated breakdown caused by warmth. However, if rapid decomposition is desired—such as in composting or soil enrichment—burying wood in warmer, moist soil can expedite the process, turning it into nutrient-rich humus within a few years.

A comparative analysis reveals that temperature’s role in wood decomposition is not linear. While moderate warmth speeds up microbial activity, extreme heat (above 100°F or 38°C) can dehydrate microorganisms, slowing decomposition. Conversely, temperatures below 50°F (10°C) reduce microbial metabolism, prolonging wood’s lifespan. This nuance highlights the importance of understanding local climate conditions when predicting or managing wood’s underground longevity.

For those seeking precise control, monitoring soil temperature with a thermometer can provide actionable insights. Aim to keep temperatures below 70°F (21°C) if preserving wood is the goal, or above this threshold for faster breakdown. Additionally, combining warmth with adequate moisture—maintaining soil humidity around 40–60%—creates an optimal environment for microbes, further hastening decomposition. This dual focus on temperature and moisture offers a practical strategy for manipulating wood’s underground fate.

Mastering Wood Carving: Timeframe for Crafting a Stunning Wood Panel

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Oxygen Exposure: Limited oxygen in soil promotes anaerobic bacteria, slowing rot

Wood buried underground doesn't rot at the same rate as wood exposed to air. The key difference lies in oxygen availability. Above ground, aerobic bacteria feast on wood, breaking it down rapidly. But beneath the surface, oxygen is scarce, creating an environment where anaerobic bacteria dominate. These microbes are far less efficient at decomposing wood, significantly slowing the rotting process.

Imagine a log left in your backyard versus one buried in your garden. The exposed log will likely crumble within a few years, while its buried counterpart could persist for decades, even centuries, depending on other factors.

This oxygen-deprived environment acts as a natural preservative. Anaerobic bacteria lack the metabolic firepower of their aerobic cousins, relying on slower, less energy-intensive processes to break down organic matter. This means wood buried underground experiences a kind of suspended animation, its cellular structure preserved for much longer than it would be above ground.

Think of it like pickling: by removing oxygen, we slow down the spoilage process, keeping food edible for longer. Similarly, limited oxygen in soil "pickles" wood, delaying its inevitable decay.

Understanding this principle has practical applications. For example, in archaeology, wooden artifacts buried in oxygen-poor environments, like waterlogged peat bogs, can survive for millennia. The famous Tollund Man, a 2,000-year-old bog body discovered in Denmark, still had his facial features and even his last meal preserved due to the anaerobic conditions of his burial site.

This knowledge can also be applied to modern construction and landscaping. When using wood in contact with soil, consider treating it with preservatives or choosing naturally rot-resistant species like cedar or redwood. However, if you're aiming for a more natural, eco-friendly approach, burying wood in well-drained soil with limited oxygen exposure can extend its lifespan significantly, reducing the need for frequent replacements.

Into the Woods Runtime: How Long is the Play?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The time it takes for wood to rot underground varies, but it typically ranges from 5 to 50 years, depending on factors like wood type, soil moisture, temperature, and oxygen levels.

Yes, hardwoods like oak or teak rot more slowly (25–50 years), while softwoods like pine or cedar decompose faster (5–15 years) due to their lower density and natural oils.

Burying wood deeper can slow rotting if it reduces exposure to oxygen and moisture, but in anaerobic (oxygen-free) conditions, certain bacteria can still break it down, though more slowly.

Pressure-treated wood lasts longer underground (10–30 years) due to preservatives, but it will eventually rot, especially in wet or acidic soil conditions.

Yes, warmer and wetter climates accelerate rotting (5–15 years), while colder or drier climates slow it down (20–50 years) due to reduced microbial activity.

![Preservation [Import]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/81+IBpvrysL._AC_UL320_.jpg)