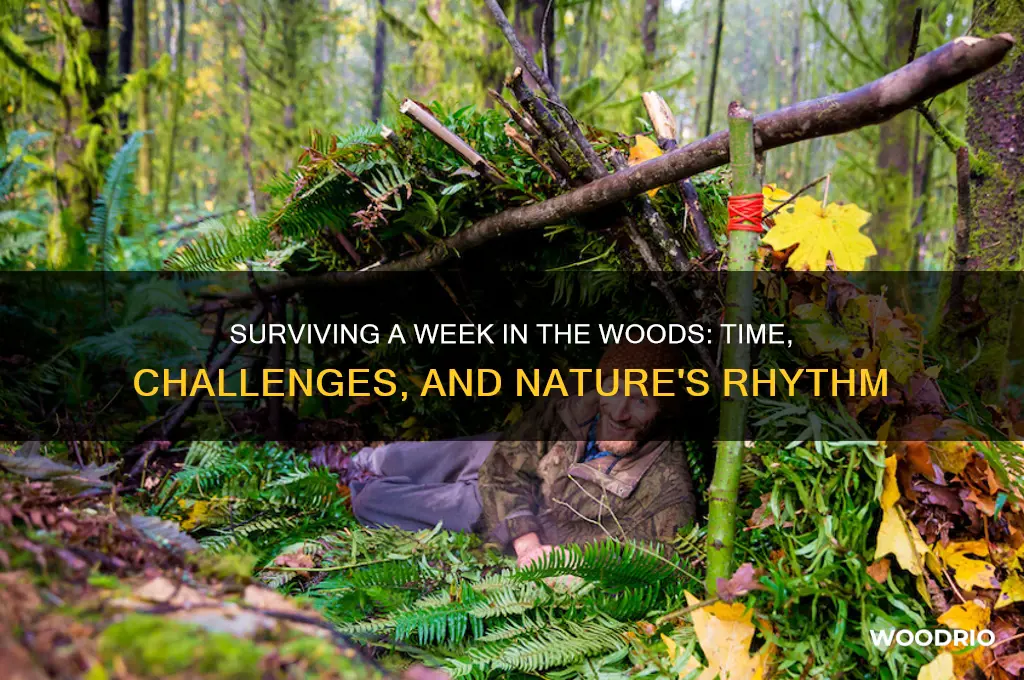

Exploring the concept of time in nature, the question how long is a week in the woods? invites a reflection on the subjective experience of duration when immersed in the natural world. Removed from the structured schedules and digital distractions of modern life, a week spent in the woods can feel both fleeting and eternal. The rhythm of the forest, dictated by the rising and setting of the sun, the chirping of birds, and the rustling of leaves, creates a sense of timelessness that contrasts sharply with the measured minutes and hours of urban existence. For some, the absence of external timekeepers allows for a deeper connection with the present moment, making each day feel expansive and rich with discovery. For others, the lack of familiar markers can distort perception, causing days to blend together in a serene, uninterrupted flow. Ultimately, a week in the woods is not just a measure of time but a transformative experience that redefines how we perceive and value the passage of moments.

Explore related products

$9.04 $16.99

What You'll Learn

- Survival Skills Basics: Essential skills for staying safe and comfortable during a week in the woods

- Food and Water Sources: Identifying edible plants, purifying water, and hunting/fishing techniques

- Shelter Building Tips: Constructing temporary shelters using natural materials and basic tools

- Navigation Without Tools: Using nature’s signs, sun, stars, and landmarks to find your way

- Wildlife Encounters: Understanding local animals, avoiding conflicts, and responding to dangerous situations

Survival Skills Basics: Essential skills for staying safe and comfortable during a week in the woods

A week in the woods is 168 hours of unpredictable weather, limited resources, and no Netflix. To survive—and thrive—you need skills that go beyond wishful thinking. Start with the basics: shelter, water, fire, and food. These aren’t just buzzwords; they’re the pillars of survival. Without them, your week could end prematurely.

Shelter first. Hypothermia kills faster than hunger. In 50°F (10°C) rain, your body temperature drops within hours. Build a debris hut or lean-to using branches and leaves. Pro tip: Angle your shelter 30 degrees from the wind to deflect rain and retain heat. If you have a tarp, secure it low to the ground to trap warmth. Always scout for dead branches overhead—they’re your silent, deadly enemies.

Water next. Dehydration sets in after 24 hours without water. Purify any source using the 1-2 punch: boil for 1 minute (at sea level) or use a filter with 0.1-micron pores. No filter? Improvise with a cloth and charcoal layer to remove sediment. Avoid stagnant water—it’s a parasite party. Carry a collapsible water bag (1-2 liters per day) and prioritize collecting water in the morning when sources are freshest.

Fire is non-negotiable. It cooks, warms, and signals. Gather tinder (dry grass, wood shavings), kindling (pencil-sized sticks), and fuel (logs). Use the hand drill or bow drill method if you lack matches. Pro tip: Store tinder in a plastic bag—moisture is fire’s arch-nemesis. Keep the fire small and manageable; a raging blaze wastes fuel and attracts attention (not always a good thing).

Food last. Your body can survive 3 weeks without it, but energy dips fast. Focus on high-calorie, easy-to-forage foods: acorns (leach tannins first), pine nuts, and cattail roots. Fishing? Use a sharp stick or improvised hook. Trapping small game? Set snares at animal trails using flexible branches. Avoid mushrooms unless 100% sure—one mistake can be fatal.

Cautionary tales: Overconfidence kills. A hiker in the Adirondacks spent 4 days lost with a broken compass. Another ignored fire safety and sparked a wildfire. Respect the woods, prepare meticulously, and adapt quickly. A week in the woods isn’t a vacation—it’s a test of resilience. Pass it, and you’ll emerge with skills sharper than your survival knife.

Wood Putty Drying Time: When to Sand for Smooth Results

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Food and Water Sources: Identifying edible plants, purifying water, and hunting/fishing techniques

In the woods, survival hinges on your ability to locate and utilize food and water sources effectively. Identifying edible plants is a critical skill, as it provides sustenance without the need for hunting or fishing. Familiarize yourself with common edible plants like dandelion, clover, and wild garlic, but always cross-reference with a reliable guide to avoid toxic look-alikes. For instance, the inner bark of pine trees is edible and rich in vitamin C, offering both nutrition and a morale boost. However, consumption should be moderate, as excessive intake can lead to digestive discomfort.

Water purification is equally vital, as untreated water can harbor pathogens like giardia and cryptosporidium. Boiling water for at least one minute at sea level (longer at higher altitudes) is the most reliable method, killing 99.99% of harmful organisms. If boiling is impractical, chemical treatments like iodine tablets (5-10 mg/L for clear water, double for cloudy) or chlorine dioxide drops (4 drops per liter) are effective alternatives. Portable filtration devices with a pore size of 0.1 microns or smaller can remove bacteria and protozoa but not viruses, making them suitable for most wilderness scenarios.

Hunting and fishing require patience, observation, and technique. For small game like rabbits or squirrels, set snares using paracord or wire in well-traveled animal paths, ensuring the loop is no larger than 4 inches in diameter to effectively catch the target. Fishing can be done with improvised hooks made from safety pins or thorns, baited with insects or small pieces of meat. Spearfishing is another option, but it demands precision and stealth, best attempted in shallow, clear waters where fish are visible. Always prioritize safety and ethical considerations, only taking what is necessary for survival.

Comparing these methods, foraging for plants is the least energy-intensive but requires knowledge and caution. Water purification is non-negotiable, with boiling being the gold standard despite its fuel requirements. Hunting and fishing yield higher caloric returns but are time-consuming and unpredictable. A balanced approach, combining foraging with occasional hunting or fishing, maximizes efficiency while minimizing risk. For instance, spending mornings gathering plants and afternoons setting traps or fishing lines optimizes resource allocation.

In practice, integrate these skills through scenario planning. Imagine you’re in a deciduous forest with a nearby stream. Start by purifying water using the boiling method, then scout for dandelion leaves and pine bark while setting snares near animal burrows. By evening, check traps and attempt fishing using a thorn hook. This systematic approach ensures a steady supply of food and water, turning a week in the woods from a daunting challenge into a manageable experience. Always remember, preparation and adaptability are your greatest tools.

Mopani Wood Durability: Lifespan in Fish Tanks Explained

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Shelter Building Tips: Constructing temporary shelters using natural materials and basic tools

In the woods, a week can feel like both an eternity and a fleeting moment, depending on your preparation. When constructing a temporary shelter, the first step is to assess your surroundings for natural materials. Look for sturdy branches, large leaves, and fallen trees. A lean-to shelter, for example, requires a strong base—ideally a fallen tree or a sturdy branch propped against a standing tree. This structure not only provides immediate protection but also minimizes energy expenditure, allowing you to focus on other survival tasks.

The key to a durable shelter lies in its foundation and framework. Start by laying a bed of dry leaves or pine needles for insulation, ensuring they are thick enough to cushion and insulate your body from the cold ground. Next, interlock branches to create a robust frame, securing them with vines or strips of bark if available. Avoid using green wood, as it tends to warp and weaken when drying. Instead, opt for dry, deadwood that retains its strength. This method not only maximizes stability but also blends seamlessly into the environment, reducing visibility to wildlife.

While constructing, consider the direction of prevailing winds and potential water runoff. Position your shelter on high ground, away from low-lying areas prone to flooding. Angle the roof slightly to shed rain or snow, using overlapping layers of bark, large leaves, or ferns for added waterproofing. A well-built shelter should not only protect from the elements but also conserve body heat, making it a critical component of survival in the woods for a week or longer.

Finally, test your shelter before fully committing to it. Spend a few hours inside during daylight to identify weaknesses, such as gaps in the roof or insufficient insulation. Adjust as needed, ensuring it can withstand wind, rain, or snow. Remember, the goal is not to build a permanent home but a functional, temporary refuge that buys you time and energy. With these tips, a week in the woods becomes less about endurance and more about adaptation, turning raw materials into a lifeline.

Tanalised Wood Durability: Lifespan, Maintenance, and Longevity Explained

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Navigation Without Tools: Using nature’s signs, sun, stars, and landmarks to find your way

In the woods, where GPS signals falter and compasses can fail, the natural world becomes your most reliable guide. The sun, for instance, rises in the east and sets in the west, a consistent pattern that can orient you even in unfamiliar terrain. By observing the direction of shadows cast by trees or rocks, you can determine the cardinal points. At noon, when the sun is at its highest, the shortest shadow points directly north in the Northern Hemisphere or south in the Southern Hemisphere. This simple technique, practiced by ancient travelers, remains one of the most effective ways to find your bearings without tools.

Stars, too, offer a celestial roadmap for nocturnal navigation. In the Northern Hemisphere, the North Star (Polaris) is a steadfast marker, located nearly directly above the North Pole. To find it, locate the Big Dipper constellation and follow the line formed by its two outermost stars, which points to Polaris. In the Southern Hemisphere, the Southern Cross constellation serves a similar purpose, though it requires a bit more skill to interpret. By aligning the longer axis of the Southern Cross with the horizon, you can estimate the direction of south. Mastering these star patterns can turn a starlit sky into a compass, guiding you through the darkest nights.

Landmarks, both natural and man-made, are another critical tool for navigation. Rivers, for example, often flow in predictable directions, typically from higher to lower elevations. By following a river downstream, you may eventually reach a populated area or a recognizable feature. Similarly, mountain ranges, large rock formations, or distinctive tree lines can serve as visual anchors, helping you maintain a consistent direction. Even subtle cues, like moss growing predominantly on the north side of trees in the Northern Hemisphere, can provide valuable orientation clues.

However, relying solely on nature’s signs requires practice and caution. Weather conditions can obscure the sun or stars, and unfamiliar landscapes may lack obvious landmarks. To mitigate these risks, combine multiple techniques whenever possible. For instance, use the sun’s position during the day and star patterns at night to cross-verify your direction. Additionally, memorize key landmarks before venturing into the woods, and always carry a mental map of your surroundings. While modern tools are convenient, the skills of natural navigation not only deepen your connection to the environment but also ensure you’re never truly lost.

Soaking Wood in Pentacryl: Optimal Time for Preservation and Results

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$8.69 $17.99

Wildlife Encounters: Understanding local animals, avoiding conflicts, and responding to dangerous situations

A week in the woods offers ample opportunity to encounter wildlife, from the curious deer to the elusive black bear. Understanding the behavior of local animals is crucial for a safe and enjoyable experience. Research the region’s fauna before your trip—know which species are active during your visit, their typical habitats, and their behaviors. For instance, black bears are more active at dawn and dusk, while moose are often found near water sources. This knowledge helps you anticipate encounters and plan accordingly.

Avoiding conflicts with wildlife begins with respecting their space. Keep a safe distance—at least 50 yards from large mammals like bears and moose, and never approach or feed any wild animal. Store food securely in bear-resistant containers or hang it at least 10 feet off the ground and 4 feet away from trees or poles. Noise can also deter unexpected encounters; hike in groups and speak loudly or carry a bear bell to alert animals of your presence. Remember, most wildlife seeks to avoid humans, so minimizing surprises benefits both parties.

Despite precautions, dangerous situations can arise. If you encounter a bear, remain calm and assess its behavior. If it hasn’t seen you, slowly back away. If it’s aware of you, speak softly and wave your arms to appear larger. Never run—bears can outpace humans. In the rare event of an aggressive encounter, use bear spray as a last resort, aiming low toward the bear’s face. For smaller predators like coyotes or aggressive birds, stand your ground, make loud noises, and throw objects if necessary. Always carry a first-aid kit and know how to treat bites or scratches, which should be cleaned immediately and monitored for infection.

Children and pets require extra vigilance during wildlife encounters. Keep kids close and educate them on the importance of staying quiet and calm. Pets should be leashed at all times, as their natural curiosity can provoke animals. For families, consider carrying a lightweight air horn to scare off potential threats without harming the animal. Teaching everyone in your group how to respond to wildlife ensures a unified and effective reaction when it matters most.

By understanding local animals, taking proactive measures to avoid conflicts, and knowing how to respond in dangerous situations, you can transform potential risks into meaningful interactions with nature. A week in the woods becomes not just a test of survival, but a chance to coexist with the wild on its terms. Preparation and respect are your greatest tools—use them wisely.

Varnished Wood Decomposition: Understanding the Breakdown Timeline

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

A week in the woods, like anywhere else, consists of 7 days.

It depends on the activities and experiences; some people find it feels longer due to the disconnect from routine, while others feel it passes quickly because of the immersive nature of being outdoors.

Prepare by packing essential gear (tent, sleeping bag, food, water, first aid kit), planning your activities, checking weather conditions, and informing someone of your itinerary for safety.

![The Wild Foods Survival Bible: [6 in 1] Your Ultimate Wilderness Dining Guide | Harvesting, Hunting, and Cooking Wild Edibles, Plants and Game with 182 Foods and 100 Step-by-Step Recipes](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/71DH+PfC6QL._AC_UL320_.jpg)