Wood, a ubiquitous material in construction, furniture, and art, has been used by humans for millennia, but determining its age can be a fascinating and complex process. The question of how old is wood delves into various scientific methods, including dendrochronology, radiocarbon dating, and visual inspection, each offering unique insights into the timber's history. From ancient trees in archaeological sites to reclaimed wood in modern homes, understanding the age of wood not only reveals its historical significance but also helps in assessing its durability, value, and environmental impact. Whether for preservation, research, or craftsmanship, unraveling the age of wood connects us to the natural world and the stories embedded within its rings and grains.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Age Determination Methods | Radiocarbon dating, Dendrochronology (tree-ring dating), Chemical analysis, Microscopic analysis |

| Radiocarbon Dating Accuracy | Up to 50,000 years old, with a margin of error of ±40 years for modern samples |

| Dendrochronology Accuracy | Precise to the exact calendar year for trees with distinct growth rings |

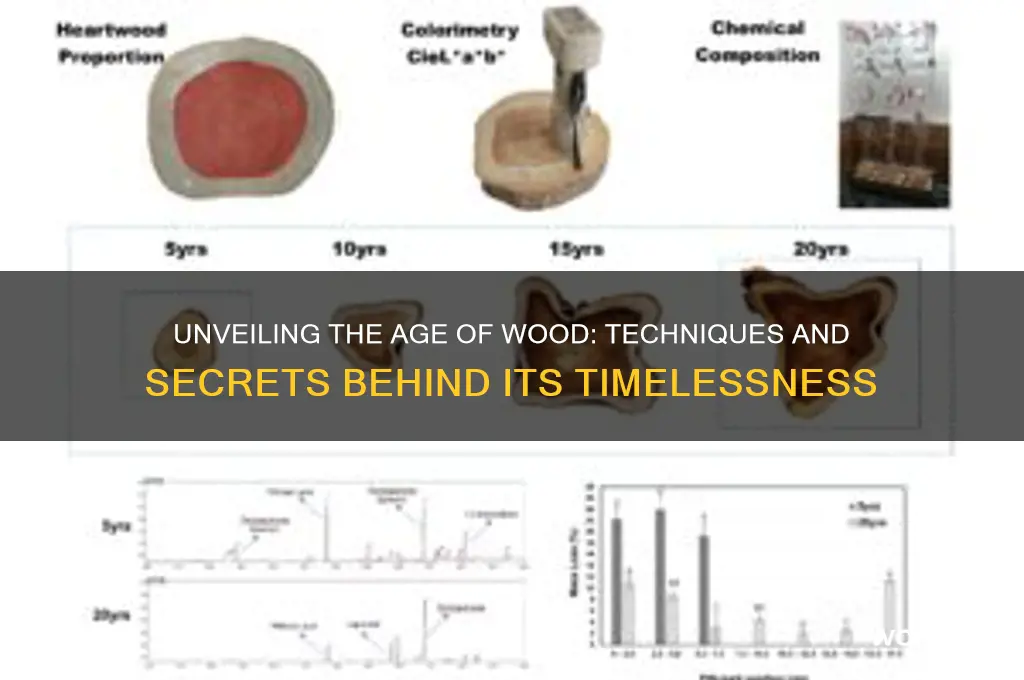

| Chemical Changes Over Time | Decrease in cellulose, increase in lignin, and accumulation of extractives |

| Physical Changes Over Time | Darkening of color, increased hardness, and reduced moisture content |

| Microscopic Changes | Cell wall thickening, increased cell collapse, and presence of fungi or insects |

| Oldest Known Wood | Approximately 360 million years old (fossilized wood from the Devonian period) |

| Longevity of Living Trees | Up to 5,000 years (Great Basin bristlecone pine, Pinus longaeva) |

| Preservation Factors | Anaerobic environments (e.g., waterlogged, buried in sediment), low oxygen, and cool temperatures |

| Common Uses of Aged Wood | Furniture, musical instruments, construction, and historical restoration |

| Environmental Impact on Aging | Climate, soil type, and exposure to elements influence aging rate |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Dendrochronology Basics: Tree-ring dating science to determine wood age accurately using growth patterns

- Carbon Dating Methods: Radiocarbon techniques for estimating wood age beyond historical records

- Wood Aging Signs: Identifying age through cracks, patina, and natural wear indicators

- Historical Context: Using artifacts and records to approximate wood age in structures

- Modern Age Tests: Advanced lab methods like cellulose analysis for precise wood dating

Dendrochronology Basics: Tree-ring dating science to determine wood age accurately using growth patterns

Trees, like silent historians, record their lives in annual growth rings. Each ring, a layer of wood added during a single growing season, holds clues to the tree's age and the environmental conditions it endured. Dendrochronology, the science of analyzing these tree rings, offers a precise method for determining the age of wood, providing insights into both the tree's life and the climate of its time.

The Science Behind the Rings

Imagine a tree's trunk as a chronological archive. Wider rings generally indicate favorable growing conditions – ample sunlight, rainfall, and nutrients. Narrower rings suggest drought, disease, or other stressors. By comparing the ring patterns of a sample to a reference chronology (a long, continuous record of ring widths from trees in the same region), dendrochronologists can pinpoint the exact year each ring formed. This technique, known as cross-dating, relies on the principle that trees in a given area experience similar environmental fluctuations, resulting in matching ring patterns.

A well-established reference chronology, spanning centuries or even millennia, acts as a calendar against which unknown samples can be compared.

Building the Timeline: A Collaborative Effort

Creating these reference chronologies is a labor-intensive process. Scientists meticulously collect samples from living trees, dead wood, and even archaeological artifacts. Each sample is carefully sanded and polished to reveal the ring patterns. The width of each ring is measured, and the resulting data is statistically analyzed to identify matching patterns across samples. Over time, these overlapping chronologies build a continuous timeline, extending back hundreds or even thousands of years.

The oldest known dendrochronological record, based on bristlecone pines in California, stretches back an astonishing 12,000 years.

Applications Beyond Age Determination

Dendrochronology's utility extends far beyond simply dating wood. By analyzing the chemical composition of individual rings, scientists can glean information about past climate conditions. Variations in isotopes, for example, can indicate changes in temperature and precipitation. Dendrochronology also aids in archaeology, helping to date wooden structures and artifacts, and in ecology, providing insights into forest health and past disturbances.

Limitations and Considerations

While powerful, dendrochronology has limitations. It requires access to wood samples with clearly defined rings, which may not always be available. Additionally, the technique is most accurate in regions with distinct seasonal variations, as these produce well-defined rings. Despite these limitations, dendrochronology remains a valuable tool for understanding the past, offering a unique window into the lives of trees and the environments they inhabited.

Identifying Pressure-Treated Wood: A Guide to Spotting Older Lumber

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Carbon Dating Methods: Radiocarbon techniques for estimating wood age beyond historical records

Radiocarbon dating, a cornerstone of archaeological and environmental science, offers a precise method for determining the age of wood, even when historical records fall silent. This technique leverages the natural decay of carbon-14, a radioactive isotope, which begins the moment an organism dies. By measuring the remaining carbon-14 in a wood sample, scientists can calculate its age with remarkable accuracy, typically within a range of 300 to 50,000 years. For older samples, other isotopes like carbon-13 or dendrochronology (tree-ring dating) are used in conjunction to extend the timeline. This method is particularly invaluable for dating ancient structures, artifacts, and environmental changes, filling gaps left by written history.

To perform radiocarbon dating on wood, a sample of at least 10–20 milligrams is required, though smaller samples can be analyzed with advanced techniques like Accelerator Mass Spectrometry (AMS). The process begins with sample preparation, where contaminants like adhesives or preservatives are removed to ensure accuracy. The wood is then combusted to produce carbon dioxide, which is converted into graphite for analysis. AMS measures the carbon-14 concentration directly, providing results with a precision of ±40 years for modern samples and ±100–200 years for older ones. Calibration is critical, as raw data must be adjusted against known records, such as tree-ring sequences, to account for fluctuations in atmospheric carbon-14 levels.

One of the most compelling applications of radiocarbon dating is in archaeology, where it has revolutionized our understanding of human history. For instance, the dating of wooden tools from the Neolithic period has revealed the spread of agriculture across Europe, while the analysis of ancient wooden structures has shed light on early civilizations. In environmental science, radiocarbon dating of wood from sediment cores helps reconstruct past climates, showing how forests responded to glacial periods or abrupt climate shifts. These insights are not just academic; they inform modern conservation efforts and climate models, bridging the gap between past and present.

Despite its power, radiocarbon dating is not without limitations. The technique’s accuracy diminishes beyond 50,000 years due to the near-complete decay of carbon-14. Additionally, contamination from younger organic materials or chemical treatments can skew results. For example, a wooden artifact treated with linseed oil in the 19th century might appear younger than it truly is. Researchers must therefore exercise caution, employing cross-verification methods like dendrochronology or potassium-argon dating for older samples. Practical tips include selecting samples from the innermost rings of trees, which are less prone to contamination, and documenting the sample’s context to ensure accurate interpretation.

In conclusion, radiocarbon dating stands as a vital tool for estimating wood age beyond the reach of historical records. Its ability to provide precise timelines has transformed fields from archaeology to climatology, offering a window into the past that was once obscured. While challenges exist, careful methodology and complementary techniques ensure its reliability. For anyone seeking to uncover the age of wood, whether for research or restoration, radiocarbon dating remains an indispensable resource, bridging the gap between the ancient and the known.

Spotting Vintage Wood Hydrangeas: A Guide to Identification

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Wood Aging Signs: Identifying age through cracks, patina, and natural wear indicators

Cracks in wood are not just flaws; they are narratives etched by time. Known as "checks," these fissures typically form as wood dries and contracts, their depth and pattern revealing age. In softwoods like pine, checks often appear within the first decade, shallow and sporadic. Hardwoods, such as oak or mahogany, resist cracking longer but develop deeper, more pronounced checks after 50–100 years. Cross-sectional cracks, called "end splits," are particularly telling—their length relative to the wood’s diameter can estimate age within 20–30-year ranges. For instance, a 2-inch diameter oak log with a 1-inch split suggests wood aged 60–80 years.

Patina, the subtle sheen or color change on wood surfaces, is a silent age indicator. Unlike cracks, patina develops from exposure to light, air, and touch. Freshly cut wood appears uniform, but aged wood exhibits a muted, uneven tone. For example, oak transitions from golden brown to rich amber over 50–75 years, while cherry wood deepens to a reddish-brown within 30–40 years. To assess patina, compare protected areas (like the underside of furniture) with exposed surfaces—greater contrast indicates older wood. However, beware of artificial patinas created by staining or smoking, which lack the natural gradient of genuine aging.

Natural wear indicators, such as rounding edges and smoothing surfaces, provide tactile clues to wood age. New wood feels sharp and defined, but decades of handling or environmental exposure soften contours. A chair leg, for instance, may lose its crisp edges after 30–50 years of use. Similarly, tool marks (like saw or plane lines) become less distinct over time due to abrasion. To test, run a fingernail along the surface—older wood yields a smoother glide. Yet, wear alone is insufficient for dating; combine it with crack and patina analysis for accuracy.

While cracks, patina, and wear are primary aging signs, context matters. Wood in arid climates cracks faster but develops patina slower than in humid environments. Indoor wood ages differently from outdoor wood—the former may show deeper patina but fewer checks. To refine age estimates, consider species-specific traits: cedar resists cracking for centuries, while walnut patinas rapidly. For practical application, document observations with photos and measurements, then cross-reference with historical usage patterns (e.g., old-growth timber in pre-1900 furniture). This layered approach transforms guesswork into informed assessment.

Charlie Woods' Age: Unveiling the Young Golfer's Journey

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Historical Context: Using artifacts and records to approximate wood age in structures

Dating wooden structures is a delicate dance between science and history. While dendrochronology (tree-ring dating) offers precise timelines for younger wood, historical context often provides the crucial first step in approximating age for older buildings. Artifacts found within or around a structure, coupled with meticulous record-keeping, become silent witnesses to its past.

A nail, for instance, can be more than just a fastener. Its shape, material, and manufacturing technique can pinpoint a specific era. Cut nails, common in the 18th and early 19th centuries, give way to wire nails in the late 19th century. Similarly, the presence of hand-hewn beams suggests a pre-industrial construction date, while machine-sawn lumber points to a later period.

Imagine a weathered barn, its beams bearing the scars of time. Within its dusty interior, a rusted hinge reveals a distinctive "strap" design, characteristic of the 1700s. Nearby, a faded newspaper fragment, used as insulation, bears a date of 1820. These artifacts, combined with the architectural style and local historical records mentioning a "new barn" on the property in the early 1800s, paint a compelling picture of the structure's age.

While artifacts provide clues, historical records are the backbone of this investigative process. Land deeds, tax records, and even personal diaries can offer invaluable insights. A meticulous search through county archives might reveal a land sale document describing a "dwelling house and outbuildings" on the property in question, dated 1789. This establishes a minimum age for the structures, even if their exact construction date remains elusive.

It's important to remember that historical context is a puzzle, not a single piece. Artifacts and records must be cross-referenced and analyzed critically. A single artifact can be misleading, and records can be incomplete or inaccurate. By combining multiple lines of evidence, we can build a more reliable picture of a wooden structure's age, connecting it to the broader tapestry of history.

Elijah Wood's Age as Frodo: A Surprising Revelation

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Modern Age Tests: Advanced lab methods like cellulose analysis for precise wood dating

Cellulose, the primary component of wood, holds secrets to its age that advanced laboratory techniques can now unlock. One such method, cellulose analysis, leverages the natural degradation of cellulose over time to provide precise age estimates. As wood ages, cellulose chains break down due to environmental factors like moisture, temperature, and microbial activity. By measuring the degree of polymerization (DP) of cellulose—essentially, the length of its molecular chains—scientists can correlate this data with known degradation rates to determine age. For instance, archaeological samples often exhibit a DP of 200–300, indicating centuries of aging, while modern wood typically has a DP above 1,000. This method is particularly useful for dating wood from 100 to 1,000 years old, filling a critical gap between radiocarbon dating (effective for older samples) and dendrochronology (limited to the lifespan of living trees).

To perform cellulose analysis, researchers first extract cellulose from a wood sample using chemical treatments like sodium chlorite to remove lignin and hemicellulose. The purified cellulose is then dissolved in a solvent, and its DP is measured via viscometry or size-exclusion chromatography. Viscometry, for example, relies on the principle that longer cellulose chains increase the viscosity of a solution. By comparing the sample’s viscosity to that of cellulose standards, scientists can calculate DP with an accuracy of ±5%. This process requires minimal sample material—as little as 10 milligrams—making it ideal for preserving valuable artifacts. However, contamination from soil or adhesives can skew results, so meticulous sample preparation is essential.

While cellulose analysis offers precision, it is not without limitations. The method assumes a consistent degradation rate, which can vary based on environmental conditions. For example, wood buried in dry, anaerobic soil degrades more slowly than wood exposed to moisture and oxygen. To account for this, researchers often calibrate their models using reference samples with known histories. Additionally, cellulose analysis cannot date wood older than 1,000 years, as DP values plateau beyond this point. In such cases, combining cellulose analysis with radiocarbon dating provides a more comprehensive age profile. For instance, a study of ancient Egyptian wooden artifacts used both methods to confirm their age within a 50-year margin, showcasing the power of multimodal approaches.

Practical applications of cellulose analysis extend beyond archaeology. In art restoration, it helps authenticate wooden artifacts by distinguishing between original materials and later repairs. In forestry, it aids in assessing the durability of timber used in construction or furniture. For hobbyists and collectors, understanding this technique can inform decisions about acquiring or preserving wooden items. To maximize accuracy, always ensure samples are free from surface treatments like varnish, which can interfere with cellulose extraction. Additionally, documenting the sample’s provenance—its origin and storage conditions—provides critical context for interpreting results.

In conclusion, cellulose analysis represents a modern leap in wood dating, offering precision and versatility for samples in the 100–1,000-year age range. By measuring cellulose degradation, this method bridges the gap between traditional dating techniques, providing a powerful tool for scientists, conservators, and enthusiasts alike. While it requires careful sample preparation and consideration of environmental factors, its ability to unlock the age of wood with minimal material makes it an invaluable asset in fields from archaeology to art restoration. As technology advances, cellulose analysis will likely become even more refined, further enhancing our understanding of wooden artifacts and their histories.

Master Rustic Wood Aging: Techniques for Authentic Vintage Charm

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The age of wood can be determined using methods like dendrochronology (tree-ring dating), radiocarbon dating, or by analyzing the wood's condition and historical context.

Dendrochronology is highly accurate for dating wood, especially in regions with well-established tree-ring chronologies, as it can pinpoint the exact year the tree was cut.

Radiocarbon dating is effective for wood up to about 50,000 years old. Beyond that, the remaining carbon-14 becomes too minimal for accurate measurement.