New Zealand’s wood age varies significantly depending on the context, whether it’s living trees, timber in construction, or archaeological artifacts. The country is home to some of the world’s oldest living trees, such as the kauri (Agathis australis), with specimens like Tāne Mahuta estimated to be over 2,000 years old. In construction, wood used in buildings or structures can range from decades to centuries old, particularly in heritage sites. Archaeologically, wood found in Māori settlements or swamp kauri (ancient kauri logs preserved in peat swamps) can date back thousands of years, with some swamp kauri specimens exceeding 50,000 years in age. Understanding the age of wood in New Zealand provides insights into its ecological, cultural, and historical significance.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Radiocarbon Dating Methods: Techniques used to determine the age of wood in New Zealand

- Native Tree Species Ages: Lifespans and growth rates of indigenous New Zealand trees

- Archaeological Wood Finds: Discoveries of ancient wood in New Zealand archaeological sites

- Kauri Tree Age Records: Notable old-growth kauri trees and their estimated ages

- Climate Impact on Aging: How New Zealand’s climate affects wood preservation and aging

Radiocarbon Dating Methods: Techniques used to determine the age of wood in New Zealand

Radiocarbon dating stands as a cornerstone in determining the age of wood in New Zealand, offering a window into the country's rich ecological and historical tapestry. This method leverages the decay of carbon-14, a radioactive isotope, to estimate the age of organic materials. In New Zealand, where wood from ancient forests and archaeological sites abounds, radiocarbon dating provides critical insights into past climates, human settlement patterns, and environmental changes. By measuring the remaining carbon-14 in a wood sample, scientists can calculate its age with remarkable precision, typically within a range of 50 to 60,000 years. This technique is particularly valuable for dating Māori artifacts, such as wooden tools and structures, which are integral to understanding New Zealand’s indigenous history.

The process begins with sample preparation, a meticulous step that ensures accuracy. Wood samples are carefully extracted to avoid contamination from external sources, such as soil or newer organic materials. Once prepared, the sample undergoes combustion to convert the organic carbon into carbon dioxide. This gas is then transformed into graphite, which is analyzed using an accelerator mass spectrometer (AMS). AMS technology has revolutionized radiocarbon dating by enabling the measurement of smaller samples and providing results with greater speed and precision. For instance, a wood fragment from a Māori waka (canoe) might yield an age estimate of 500 years, shedding light on early Polynesian navigation and settlement.

Despite its reliability, radiocarbon dating is not without limitations. One challenge is the "old wood" problem, where wood from ancient trees may appear older than the context in which it was found. This occurs because trees can live for centuries, and the carbon-14 in their outer rings may not reflect the period of human use. To mitigate this, researchers often cross-reference radiocarbon dates with other dating methods, such as dendrochronology (tree-ring dating), or analyze multiple samples from the same site. Additionally, calibration is essential, as the concentration of carbon-14 in the atmosphere has fluctuated over time due to factors like solar activity and nuclear testing. Calibration curves, such as the Southern Hemisphere curve (SHCal20), are used to convert raw radiocarbon ages into calendar years, ensuring accurate dating for New Zealand’s unique environmental context.

Practical applications of radiocarbon dating in New Zealand extend beyond archaeology. In ecology, it helps track changes in forest composition and fire regimes over millennia. For example, kauri trees (Agathis australis) store detailed climate records in their rings, and radiocarbon dating of buried kauri wood has revealed insights into past droughts and temperature shifts. In conservation, this method aids in identifying the age of endangered tree species, guiding efforts to protect them. For enthusiasts or researchers, collaborating with specialized labs, such as the Rafter Radiocarbon Laboratory in New Zealand, ensures access to state-of-the-art equipment and expertise.

In conclusion, radiocarbon dating is an indispensable tool for unraveling the age of wood in New Zealand, bridging the gap between the past and present. Its precision, combined with careful sample handling and calibration, allows scientists to reconstruct histories, from Māori cultural practices to ecological transformations. While challenges like the "old wood" problem persist, ongoing advancements in technology and methodology continue to enhance its reliability. Whether for archaeological, ecological, or conservation purposes, radiocarbon dating remains a vital technique for exploring New Zealand’s wooden legacy.

Avery Woods Kids' Ages: Unveiling the Mystery of Their Youth

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Native Tree Species Ages: Lifespans and growth rates of indigenous New Zealand trees

New Zealand’s indigenous forests are home to some of the world’s most ancient and resilient tree species, with lifespans that can span centuries or even millennia. Among these, the *kahikatea* (Dacrycarpus dacrydioides) stands out as one of the tallest and longest-living trees, often reaching ages of 600 years or more. Its slow growth rate—averaging just 0.5 to 1 millimeter in diameter per year—is a testament to its endurance, thriving in swampy, low-lying areas where it dominates the canopy. This species’ longevity is not just a biological marvel but also a historical archive, with some specimens bearing witness to centuries of environmental change.

Contrast the *kahikatea* with the *pōhutukawa* (Metrosideros excelsa), a coastal icon often referred to as New Zealand’s Christmas tree. While it may not match the *kahikatea*’s age, the *pōhutukawa* can still live for 500 to 1,000 years, its gnarled branches and vibrant blooms a symbol of resilience against salt spray and strong winds. Its growth rate is modest, typically 10 to 20 centimeters per year in height, but its ability to regenerate from old wood—a process known as lignotuberous resprouting—ensures its survival even after severe damage. This adaptability makes it a prime example of how indigenous species evolve to thrive in challenging environments.

For those seeking a tree with both rapid growth and impressive lifespan, the *tōtara* (Podocarpus totara) offers a compelling case. Capable of living for over 1,000 years, this conifer grows at a rate of 20 to 30 centimeters per year in ideal conditions, making it both a long-term ecological asset and a culturally significant species for Māori. Its durable wood, once used for carving waka (canoes), highlights the interplay between biological resilience and human history. However, its growth is highly dependent on soil quality and moisture, a reminder that even the hardiest species have specific needs.

Practical considerations for landowners or conservationists include understanding the growth requirements of these species. For instance, *kahikatea* thrives in wet soils with high organic content, while *pōhutukawa* prefers well-drained coastal soils. Planting native trees for long-term carbon sequestration or habitat restoration requires patience, as their slow growth means decades or even centuries before they reach maturity. Yet, their longevity ensures that such efforts yield benefits for generations to come, making them invaluable in the fight against climate change and biodiversity loss.

In conclusion, the ages and growth rates of New Zealand’s native trees are not just biological data points but stories of survival, adaptation, and cultural significance. From the towering *kahikatea* to the resilient *pōhutukawa* and the versatile *tōtara*, each species offers unique insights into the interplay between time, environment, and life. By understanding and preserving these trees, we not only honor their past but also secure a legacy for the future.

Old Taurus 85 Wood Grips: Full-Size Fit and Comfort Explored

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Archaeological Wood Finds: Discoveries of ancient wood in New Zealand archaeological sites

New Zealand’s archaeological sites have yielded remarkable discoveries of ancient wood, offering a window into the country’s pre-colonial past. Radiocarbon dating has revealed that some of these wooden artifacts date back over 500 years, with the oldest examples found in Māori pā (fortified villages) and storage pits. These finds include tools, weapons, and structural elements, showcasing the ingenuity of early Māori settlers in utilizing local timber resources. Kauri wood, prized for its durability, is among the most significant discoveries, with some specimens preserved in peat bogs for centuries.

Analyzing these wooden artifacts provides critical insights into the environmental and cultural history of New Zealand. For instance, the presence of kauri wood in archaeological layers helps scientists reconstruct past climates, as kauri trees are highly sensitive to environmental changes. Additionally, the craftsmanship evident in these wooden tools and structures highlights the advanced skills of Māori artisans. By studying the wear patterns and tool marks, archaeologists can infer how these objects were used and the daily lives of those who created them.

One notable discovery is the Wairau Bar site, one of New Zealand’s earliest known settlements, where wooden artifacts dating back to the 13th century have been unearthed. These include adzes, fish hooks, and canoe fragments, all carved from native woods like totara and maire. The preservation of these items in the site’s waterlogged soil has allowed researchers to study their construction techniques in detail. This site serves as a prime example of how ancient wood can provide tangible evidence of early human activity in the region.

For those interested in exploring these discoveries, visiting museums like the Auckland War Memorial Museum or Te Papa in Wellington is highly recommended. These institutions display well-preserved wooden artifacts alongside interpretive exhibits that explain their historical and cultural significance. Additionally, participating in guided archaeological tours of sites like Wairau Bar can offer a hands-on understanding of how these ancient woods are uncovered and studied.

In conclusion, the discoveries of ancient wood in New Zealand’s archaeological sites are more than just relics of the past; they are vital tools for understanding the country’s history and environment. From climate reconstruction to cultural heritage, these wooden artifacts bridge the gap between modern society and the lives of early settlers. By preserving and studying them, we ensure that their stories continue to inform and inspire future generations.

Sam Wood and Snezana Markoski's Age Difference Explored

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Kauri Tree Age Records: Notable old-growth kauri trees and their estimated ages

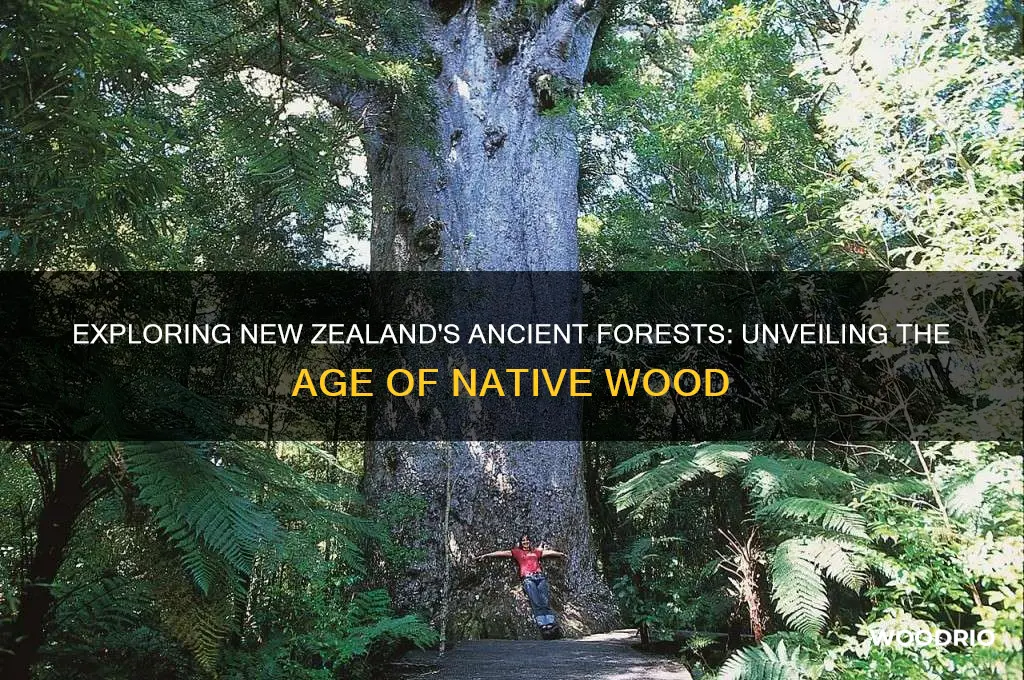

New Zealand's kauri trees (Agathis australis) are among the most ancient living organisms on Earth, with some specimens dating back millennia. These giants of the forest have stood witness to centuries of environmental change, human history, and ecological evolution. Their age records not only highlight their biological significance but also underscore the urgent need for conservation efforts to protect these living relics.

One of the most notable old-growth kauri trees is Tāne Mahuta, located in the Waipoua Forest. Estimated to be between 1,250 and 2,500 years old, this tree stands as a symbol of resilience and longevity. Its name, meaning "Lord of the Forest," reflects its majestic presence, with a girth of over 13.77 meters and a height of approximately 51.5 meters. Tāne Mahuta’s age is not just a number; it represents a living connection to New Zealand’s pre-human landscape, a time when kauri forests dominated the northern regions of the North Island.

Another remarkable example is Te Matua Ngahere, also in the Waipoua Forest, which is estimated to be between 2,000 and 3,000 years old. Translating to "Father of the Forest," this tree is shorter but broader than Tāne Mahuta, with a more gnarled and weathered appearance. Its age places it among the oldest known kauri trees, and its survival is a testament to the species’ ability to endure centuries of climatic shifts and environmental pressures. These trees are not just biological wonders; they are also cultural treasures, deeply revered by Māori communities for their spiritual and historical significance.

Estimating the age of kauri trees is a complex process, often involving dendrochronology (tree-ring dating) and radiocarbon analysis. However, because kauri trees do not produce distinct annual rings, traditional dendrochronology is challenging. Instead, scientists rely on carbon dating of wood samples and soil cores to approximate their age. This method, while precise, requires careful extraction to avoid damaging the trees, emphasizing the delicate balance between scientific inquiry and conservation.

The age records of these kauri trees serve as a reminder of the fragility of old-growth forests in the face of modern threats. Diseases like kauri dieback, caused by the oomycete Phytophthora agathidicida, pose a significant risk to these ancient trees. Conservation efforts, including controlled access to kauri forests and public awareness campaigns, are critical to ensuring their survival for future generations. By understanding and appreciating the age and significance of these trees, we can better advocate for their protection and the preservation of New Zealand’s unique natural heritage.

Does Sky Flower Bloom on Old Wood? Gardening Insights

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Climate Impact on Aging: How New Zealand’s climate affects wood preservation and aging

New Zealand's temperate maritime climate, characterized by mild temperatures, high humidity, and frequent rainfall, creates a unique environment for wood aging and preservation. These conditions, while generally favorable for lush forests, pose specific challenges and opportunities for wood durability. Understanding how climate interacts with wood is crucial for builders, artisans, and homeowners seeking to maximize the lifespan of wooden structures and artifacts.

Wood in New Zealand ages differently depending on its exposure to the elements. In regions with high rainfall, such as the West Coast of the South Island, wood is more susceptible to moisture absorption, leading to rot and fungal decay. Conversely, drier areas like Central Otago experience less moisture-related degradation but may face increased UV exposure, causing surface cracking and discoloration. The interplay between moisture and temperature fluctuations accelerates the breakdown of lignin and cellulose, the primary components of wood, making climate control a critical factor in preservation.

To combat these effects, traditional and modern preservation methods must be tailored to New Zealand's climate. For outdoor structures, using naturally durable timber species like totara or kauri, which contain natural oils and resins resistant to decay, is a proven strategy. Alternatively, pressure-treating wood with preservatives like copper azole (at concentrations of 0.4%–0.6% for above-ground use) can significantly enhance its resistance to rot and insect damage. For indoor applications, maintaining consistent humidity levels (ideally between 40%–60%) and moderate temperatures (18°C–22°C) prevents warping and splitting, ensuring longevity.

A comparative analysis of wood aging in New Zealand versus drier climates, such as Australia or the southwestern United States, highlights the importance of moisture management. In arid regions, wood primarily degrades due to UV radiation and temperature extremes, whereas in New Zealand, moisture-driven decay is the dominant threat. This distinction underscores the need for region-specific preservation techniques, such as applying water-repellent sealants in wetter areas and UV-protective coatings in drier zones.

For practical application, homeowners can take proactive steps to protect wood in New Zealand's climate. Regularly inspecting wooden structures for signs of moisture penetration, such as discoloration or soft spots, allows for early intervention. Applying a breathable wood sealant every 2–3 years helps reduce moisture absorption while allowing the wood to "breathe." Additionally, ensuring proper ventilation in enclosed spaces, like decks or fences, minimizes the risk of trapped moisture, which can accelerate decay. By adapting preservation methods to the local climate, New Zealanders can preserve the beauty and functionality of wood for generations.

Roy Wood's Age: Unveiling the Wizard's Timeless Legacy

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The age of wood in New Zealand varies widely, from recently harvested timber to ancient swamp kauri, some of which can be over 50,000 years old.

Swamp kauri refers to ancient kauri trees (Agathis australis) that were buried and preserved in swamps thousands of years ago. It is so old because the anaerobic conditions in the swamps prevented decay, preserving the wood for millennia.

Yes, New Zealand is home to some of the oldest living trees, such as the kahikatea (white pine), which can live for over 600 years, and the kauri, which can live for more than 2,000 years.

The age of wood is typically determined using radiocarbon dating (for ancient wood like swamp kauri) or dendrochronology (tree-ring dating) for living or recently felled trees.

Yes, it is legal to harvest and sell swamp kauri in New Zealand, but it is regulated. Extraction must comply with environmental and resource management laws to ensure sustainability and protection of natural habitats.

![Report on the Timber Industry of New Zealand 1906-7 1907 [Leather Bound]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/617DLHXyzlL._AC_UY218_.jpg)