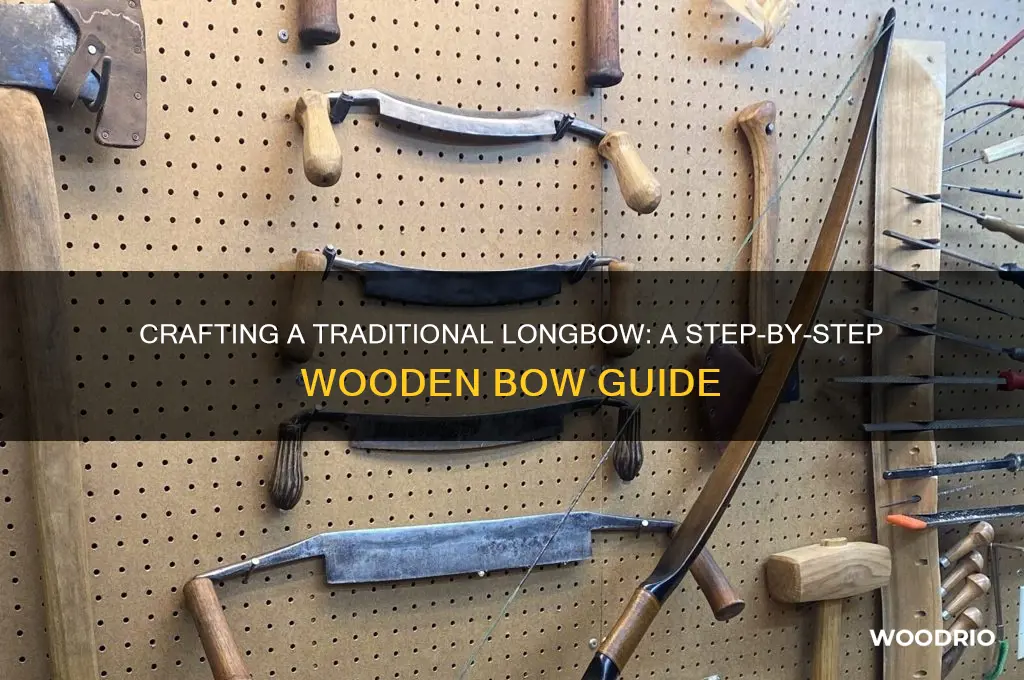

Crafting a longbow from wood is a rewarding yet intricate process that combines traditional woodworking skills with an understanding of archery principles. To begin, select a suitable hardwood such as yew, ash, or hickory, ensuring the wood is straight-grained and free of defects. The bow’s design starts with roughing out the shape, tapering the limbs for flexibility while maintaining a sturdy handle section. Careful carving and tillering follow, gradually bending the limbs to achieve the desired curve and balance, ensuring both sides flex evenly. Sanding and smoothing the surface enhance the bow’s performance and durability, while a protective finish, like linseed oil, preserves the wood. Finally, attaching a bowstring completes the project, transforming raw timber into a functional and elegant longbow.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Wood Type | Seasoned hardwoods like Osage orange, yew, or hickory are preferred for their strength and flexibility. |

| Wood Seasoning | Wood should be air-dried for at least 6 months to several years to reduce moisture content and prevent warping. |

| Bow Length | Typically 5 to 6 feet (1.5 to 1.8 meters) for a longbow. |

| Tillering | The process of shaping the bow limbs to ensure they bend evenly. This is done by gradually removing wood from the belly (outer side) of the limbs. |

| Handle Design | The handle should be slightly thicker and more rigid than the limbs, often with a flat or slightly curved grip area. |

| String Material | Traditional materials include linen or hemp, but modern synthetic materials like Dacron are commonly used for durability. |

| String Length | The string should be approximately 3 inches (7.6 cm) shorter than the bow's length to achieve proper brace height. |

| Brace Height | The distance between the string and the belly of the handle, typically 6 to 8 inches (15 to 20 cm) for a longbow. |

| Draw Weight | Varies based on user preference, but typically ranges from 30 to 60 pounds for a functional longbow. |

| Tools Required | Drawknife, spokeshave, rasp, sandpaper, bow string, and a tillering stick or tool for even bending. |

| Safety Precautions | Always wear safety goggles, work in a well-ventilated area, and ensure the bow is properly tillered to avoid breakage. |

| Finishing | Apply a light coat of natural oil (e.g., linseed oil) to protect the wood, but avoid excessive finish that could affect flexibility. |

| Testing | Gradually increase draw weight during testing to ensure the bow is safe and functional before full use. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Selecting the Right Wood Type

The choice of wood is the backbone of your longbow's performance and durability. Different species offer unique combinations of strength, flexibility, and workability, each suited to specific bow designs and archer preferences. Hardwoods like Osage orange, yew, and hickory are traditional favorites, prized for their natural resilience and ability to store and release energy efficiently. Softer woods like cedar or pine, while easier to work with, lack the necessary strength for powerful bows and are more prone to deformation under tension.

Understanding the characteristics of various wood types is crucial for crafting a bow that not only looks impressive but also shoots accurately and lasts for years.

Consider the classic yew wood, a historical staple for longbows. Its unique grain structure, with a strong heartwood and flexible sapwood, allows for a natural composite material within a single piece of wood. This makes yew ideal for self bows, where the entire bow is crafted from a single stave. However, yew can be challenging to source and requires careful seasoning to prevent warping. For beginners, easier-to-find alternatives like maple or ash offer good strength and workability, though they may not match yew's natural elasticity.

Remember, the wood's density and grain pattern directly influence the bow's draw weight and shooting characteristics.

When selecting wood, prioritize straight, clear grain with minimal knots or defects. These imperfections can create weak points, leading to potential failure under the immense stress a drawn bow experiences. Look for quartersawn or riftsawn boards, as these cuts showcase the grain pattern most favorably for bow making. Avoid woods with excessive resin pockets or irregular grain patterns, as these can compromise the bow's structural integrity.

Don't underestimate the importance of proper seasoning. Freshly cut wood contains moisture that needs to be gradually removed to prevent cracking and warping. Air-drying for at least a year per inch of thickness is recommended, followed by a slow kiln-drying process for optimal stability. Rushing this step can lead to a bow that twists, loses its shape, or even breaks during use.

Ultimately, the "right" wood type depends on your skill level, desired bow characteristics, and available resources. Research different wood species, consider their availability and cost, and don't be afraid to experiment with less traditional options. Remember, the art of bow making lies in understanding the unique qualities of each wood type and harnessing them to create a weapon that is both beautiful and functional.

COVID-19 Survival on Wood Surfaces: Duration and Safety Tips

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Preparing and Shaping the Stave

Selecting the right wood for your longbow stave is critical, as it determines both the bow's performance and longevity. Hardwoods like Osage orange, yew, or hickory are traditional choices due to their strength and flexibility. Avoid softwoods or woods prone to splitting. Once you’ve chosen your stave, inspect it for straight grain, as this ensures even bending. A crooked or twisted grain can lead to weak spots or failure under tension. If the wood has bark, remove it carefully with a drawknife or spokeshave to expose the grain and begin shaping.

Shaping the stave requires precision and patience. Start by marking the centerline along the length of the wood, ensuring symmetry in your cuts. Use a hatchet or bandsaw to rough out the bow’s limbs, leaving extra material for final adjustments. The limbs should taper gracefully, thicker at the handle (grip) and narrowing toward the tips. Aim for a thickness of approximately 1/2 inch at the handle and 1/4 inch at the tips for a standard 6-foot bow. Over-thinning the limbs can compromise strength, while leaving them too thick reduces flexibility.

As you refine the shape, consider the bow’s bend (tiller). A well-tillered bow bends evenly along its length, avoiding excessive stress on any single point. Use a tiller board or a simple jig to test the bend, marking areas that need further thinning. Work gradually, removing small amounts of wood at a time to avoid over-shaping. Sanding with progressively finer grits (80 to 220) smooths the surface and prepares the wood for finishing, enhancing both aesthetics and durability.

Caution is paramount during this stage. Always work with the grain to prevent tearing or splintering. Keep your tools sharp to ensure clean cuts, and wear safety gear, including gloves and eye protection. Over-enthusiasm with shaping tools can ruin hours of work, so maintain a steady hand and a mindful approach. Remember, the goal is not just to create a functional bow but to craft a balanced, elegant tool that reflects both skill and respect for the material.

Minwax Wood Filler Drying Time: Quick Guide for Perfect Results

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Carving the Bow Limbs

The limbs of a longbow are its powerhouse, storing and releasing energy with each draw. Carving them demands precision and an understanding of wood grain. Unlike the handle, which prioritizes stability, the limbs need flexibility. This means working with the wood's natural tendencies, not against them. Straight, even grain is crucial; any deviations can lead to weak spots or, worse, failure under tension. Select a wood species known for its strength and flexibility, like Osage orange, yew, or hickory, and ensure the grain runs parallel to the length of the limb.

Begin by roughing out the limb shape, removing excess material while leaving ample wood for refinement. Use a drawknife or spokeshave for this initial shaping, working from the center outward to avoid tear-out. As you progress, constantly check the symmetry of both limbs. Even a slight imbalance will affect the bow's performance, causing it to twist or bend unevenly. Mark the desired width and thickness along the length of each limb, tapering them from the handle (the "grip") to the tips. The limbs should be thicker and wider near the handle, gradually narrowing to a thinner, more flexible profile at the tips.

Refine the limbs with a rasp or coarse file, smoothing the curves and ensuring a consistent taper. This stage requires patience; rushing can lead to over-carving or uneven thickness. Test the flexibility periodically by gently bending the limbs. They should flex smoothly without stiffness or resistance. If one limb feels stiffer, carefully remove more material from its inner face, always working with the grain. Remember, the goal is to create a gradual, natural curve that maximizes energy storage without compromising the wood's integrity.

Once the limbs are shaped, sand them progressively with finer grits, starting at 80-grit and finishing with 220-grit or higher. Smooth limbs reduce friction on the bowstring and prevent splinters. Inspect the wood for any cracks, knots, or defects that might weaken the limbs. Even small imperfections can become critical under the stress of a drawn bow. If in doubt, err on the side of caution and reinforce the area with a natural fiber backing or reconsider the wood choice. A well-carved limb is not just about aesthetics; it’s about creating a functional, reliable tool that performs consistently shot after shot.

Durability of Permanent Wood Foundations: Lifespan and Longevity Explained

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Adding the Bowstring Groove

The bowstring groove is a critical feature of a longbow, serving as the channel that guides the string and ensures efficient energy transfer. Its placement and depth directly impact the bow's performance, affecting both accuracy and power. To begin, mark the groove’s location approximately 1/8 inch from the belly (front) of the bow, ensuring symmetry along the entire length of both limbs. Use a sharp pencil and a straightedge for precision, as even minor asymmetry can lead to torque or uneven bending.

Carving the groove requires patience and the right tools. A narrow chisel or a specialized groove-cutting tool works best for this task. Start by making shallow passes along the marked line, gradually deepening the groove to about 1/16 inch. Avoid removing too much material at once, as this can weaken the wood. For hardwoods like hickory or maple, consider softening the wood slightly with steam or warm water to reduce the risk of splitting. Always work in the direction of the grain to maintain structural integrity.

A common mistake is neglecting to round the edges of the groove. Sharp edges can cut into the bowstring over time, leading to premature wear or failure. Use a small round file or sandpaper to smooth the groove’s interior, ensuring a consistent radius. This step not only prolongs the life of the string but also reduces friction, allowing for smoother draws and releases.

Comparing traditional and modern approaches reveals a shift in groove design. Historically, bowyers often used a V-shaped groove, which was simpler to carve but less forgiving with string alignment. Contemporary designs favor a U-shaped groove, which provides better string support and reduces the risk of lateral movement. For beginners, the U-shape is recommended for its ease of use and reliability.

In conclusion, adding the bowstring groove is a blend of precision and craftsmanship. By carefully marking, carving, and refining the groove, you ensure the bow’s functionality and longevity. Take your time, prioritize symmetry, and pay attention to detail—this small feature plays a disproportionately large role in the bow’s overall performance.

Durability of Early Hominid Wooden Tools: Lifespan and Preservation Insights

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Finishing and Testing the Bow

The final stages of crafting a wooden longbow are as critical as the initial carving. Finishing the bow involves more than aesthetics; it’s about enhancing durability, performance, and safety. Begin by sanding the entire surface with progressively finer grits (start with 120-grit, end with 400-grit) to remove tool marks and splinters. Pay special attention to the handle and limbs, as these areas endure the most stress. Apply a thin coat of natural oil (like linseed or tung oil) to protect the wood from moisture without compromising flexibility. Avoid synthetic finishes like polyurethane, which can stiffen the wood and reduce the bow’s efficiency.

Testing the bow is a delicate balance of patience and precision. Start by dry-firing the bow (shooting without an arrow) to check for structural integrity. Listen for cracks or unusual sounds, which may indicate weak spots. Gradually increase the draw weight, but never exceed the wood’s natural limits—overstressing can lead to permanent damage or breakage. Use a tillering stick or a straight edge to ensure the limbs bend evenly; uneven bending suggests adjustments are needed. This step is crucial for both performance and safety, as an unbalanced bow can fail unpredictably.

A persuasive argument for thorough testing lies in the bow’s intended use. If you plan to hunt or compete, reliability is non-negotiable. Test the bow with actual arrows at varying distances, observing flight patterns and impact consistency. Adjust the string’s brace height (distance from the string to the belly of the bow) to fine-tune accuracy. For beginners, start with lighter draw weights (20–30 lbs) and gradually increase as strength and technique improve. Remember, a well-tested bow not only performs better but also reduces the risk of injury or equipment failure in critical moments.

Comparing traditional and modern approaches to finishing reveals a trade-off between authenticity and practicality. Historically, bowyers relied on natural materials like animal fat or pine pitch for protection. While these methods preserve the bow’s rustic charm, they require frequent reapplication. Modern oils and waxes offer longer-lasting protection but may alter the wood’s appearance. For purists, a blend of beeswax and linseed oil strikes a balance, providing durability without sacrificing tradition. Ultimately, the choice depends on the bow’s purpose—display pieces may prioritize aesthetics, while working bows demand functionality.

In conclusion, finishing and testing a wooden longbow is a meticulous process that bridges craftsmanship and functionality. Sanding and oiling protect the wood while preserving its natural properties, while systematic testing ensures the bow performs reliably under stress. Whether you’re a traditionalist or a pragmatist, the final steps of bowmaking demand attention to detail. A well-finished and thoroughly tested bow is not just a tool but a testament to the bowyer’s skill and the wood’s potential. Treat these stages with care, and your longbow will reward you with years of service.

Perfect Timing: Sanding Wood After Priming for Flawless Results

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Hardwoods like Osage orange, yew, hickory, or maple are ideal for long bows due to their strength, flexibility, and durability.

Choose a straight, clear piece of wood free from knots, cracks, or twists. Ensure it’s seasoned (dried) to reduce warping and splitting.

Basic tools include a drawknife, spokeshave, rasp, sandpaper, and a bow string. A bandsaw or handsaw can also be useful for initial shaping.

Tiller the bow by gradually removing wood from the belly (front) until it bends evenly along its length when drawn. Use a tiller stick or string to check symmetry.