Old wooden ships managed to withstand rot and decay through a combination of meticulous craftsmanship, strategic material selection, and innovative preservation techniques. Shipbuilders often chose durable, naturally rot-resistant woods like oak, teak, or cedar, which contain high levels of tannins and oils that deter pests and fungi. Additionally, they employed methods such as creosote treatment, copper sheathing to prevent worm infestations, and regular maintenance, including scraping and repainting. Proper ventilation and drainage systems were also crucial to prevent moisture buildup, a primary cause of rot. These practices, combined with the ships' constant exposure to saltwater, which acted as a natural preservative, allowed wooden vessels to endure for decades, even centuries, despite the harsh marine environment.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Wood Selection | Used naturally rot-resistant woods like oak, teak, cedar, and pine with high tannin content. |

| Copper Sheathing | Copper or copper alloy sheets nailed to the hull to prevent shipworm and fouling organisms. |

| Pitch and Tar Coating | Hulls coated with pitch, tar, or pine resin to create a waterproof barrier against moisture. |

| Ventilation and Airflow | Designed with ventilation to reduce moisture buildup inside the ship. |

| Regular Maintenance | Frequent inspections, cleaning, and reapplication of protective coatings. |

| Sacrificial Planking | Outer layers of wood were easily replaceable, protecting the inner structure. |

| Design and Construction Techniques | Built with overlapping planks (clinker or carvel construction) to minimize water ingress. |

| Use of Creosote | Creosote-treated wood was sometimes used for its preservative properties. |

| Ballast and Weight Distribution | Proper ballast placement prevented hull distortion and reduced stress on the wood. |

| Avoidance of Iron Fastenings | Used non-corrosive materials like wood, copper, or galvanized fasteners to prevent decay. |

| Antifouling Measures | Regular cleaning of barnacles and other marine growth to prevent water retention. |

| Storage and Dry Docking | Ships were periodically dried out in docks to prevent prolonged exposure to moisture. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Use of Hardwoods: Durable woods like oak naturally resist rot due to their dense structure and high tannin content

- Pitch and Tar Coating: Ships were coated with pitch and tar to waterproof and protect wood from moisture

- Copper Sheathing: Copper plates were nailed to hulls to prevent worm damage and reduce fouling

- Regular Maintenance: Crews constantly inspected, cleaned, and repaired ships to prevent rot and decay

- Ventilation and Drainage: Proper design allowed air circulation and water drainage, minimizing dampness and rot

Use of Hardwoods: Durable woods like oak naturally resist rot due to their dense structure and high tannin content

The choice of wood was critical in ensuring the longevity of old wooden ships. Among the myriad options, hardwoods like oak stood out as the premier choice for shipbuilders. Their dense structure and high tannin content provided a natural defense against rot, a relentless enemy of wooden vessels. Tannins, organic compounds found in high concentrations in oak, act as a natural preservative, deterring fungi and insects that would otherwise hasten decay. This inherent resistance made oak the backbone of maritime construction, from the keel to the mast.

Consider the construction process: shipbuilders would select oak timber with care, often choosing mature trees with tight grain patterns. The denser the wood, the more resistant it was to water absorption, a key factor in preventing rot. Oak’s ability to repel moisture while maintaining structural integrity was unparalleled. For instance, the frames of ships, constantly exposed to seawater, were almost exclusively made from oak. This strategic use of hardwood ensured that even in the harshest conditions, the ship’s structure remained sound.

A practical tip for modern enthusiasts or restorers: when sourcing wood for maritime projects, prioritize oak with a high tannin content. Look for timber that has been air-dried for at least two years, as this reduces moisture content and enhances durability. Additionally, treat the wood with a tannin-rich preservative, such as a solution of oak bark extract in water (1:10 ratio), to bolster its natural defenses. This step, though time-consuming, can significantly extend the life of wooden components.

Comparatively, softer woods like pine, though lighter and easier to work with, lack the durability of oak. They require frequent treatment with preservatives and are more susceptible to rot, especially in wet environments. Oak, on the other hand, can withstand decades of exposure with minimal maintenance. Historical examples, such as the *Mary Rose* and *Vasa*, both constructed primarily from oak, have survived centuries, a testament to the wood’s resilience. While these ships eventually succumbed to time, their remains provide invaluable insights into the effectiveness of hardwoods in shipbuilding.

In conclusion, the use of hardwoods like oak was not merely a tradition but a science-backed strategy. Their dense structure and high tannin content created a natural barrier against rot, ensuring the longevity of wooden ships. For anyone involved in maritime restoration or construction, understanding and leveraging these properties can make the difference between a vessel that lasts decades and one that deteriorates prematurely. Oak’s legacy in shipbuilding remains unmatched, a reminder of nature’s ingenuity in solving human challenges.

Do Peonies Grow on Old Wood? Uncovering the Truth

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Pitch and Tar Coating: Ships were coated with pitch and tar to waterproof and protect wood from moisture

Wooden ships, constantly exposed to saltwater, rain, and humidity, faced a relentless enemy: rot. Left unprotected, wood absorbs moisture, swelling and becoming a feast for fungi and shipworms. Pitch and tar, viscous black substances derived from pine trees and coal, emerged as the ancient mariners' secret weapon. These natural waterproofing agents formed a barrier, sealing the wood against the relentless assault of moisture.

Imagine a thick, sticky blanket draped over the ship's hull, repelling water like a duck's feathers. This protective coating wasn't just slathered on haphazardly. Skilled shipwrights meticulously heated the pitch and tar, transforming them into a pourable consistency. Using brushes and mops, they applied layer upon layer, ensuring every nook and cranny was covered. This labor-intensive process, often repeated annually, was crucial for the ship's longevity.

The effectiveness of pitch and tar wasn't merely anecdotal. Archaeological evidence supports their use. Shipwrecks unearthed after centuries underwater often reveal remnants of this black coating, a testament to its durability. The Mary Rose, Henry VIII's flagship, sank in 1545 and was raised in 1982. Despite centuries submerged, significant portions of its hull remained intact, preserved by the pitch and tar coating. This real-world example underscores the crucial role these substances played in extending the lifespan of wooden vessels.

While modern synthetic materials have largely replaced pitch and tar in shipbuilding, their historical significance cannot be overstated. They were the cornerstone of maritime technology for millennia, enabling exploration, trade, and the expansion of civilizations across the globe. Understanding their use offers a glimpse into the ingenuity of our ancestors and the challenges they overcame to conquer the seas.

Xavier Woods' Age: Unveiling the WWE Star's Surprising Birth Year

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$17.32

Copper Sheathing: Copper plates were nailed to hulls to prevent worm damage and reduce fouling

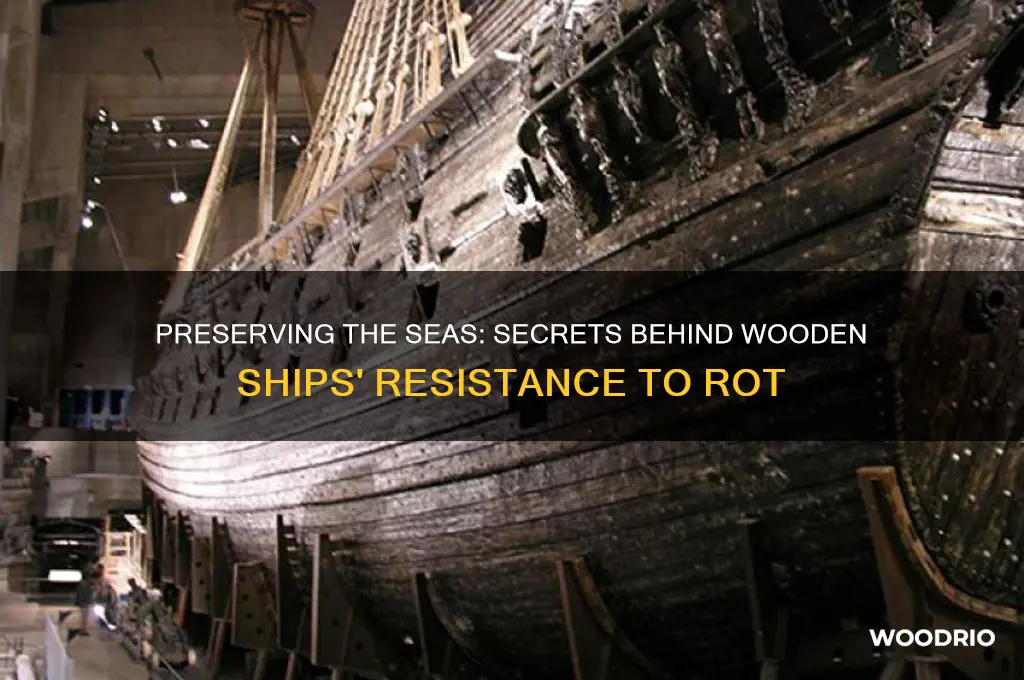

Wooden ships, despite their vulnerability to the elements, managed to endure centuries of maritime travel thanks to innovative protective measures. One such method, copper sheathing, emerged as a pivotal solution to combat the relentless threats of worm damage and fouling. By the 18th century, shipbuilders began nailing copper plates to the hulls of vessels, a practice that revolutionized naval architecture and extended the lifespan of wooden ships. This technique not only safeguarded the wood from shipworms but also minimized the accumulation of barnacles, algae, and other marine organisms that could slow a ship’s speed and efficiency.

The effectiveness of copper sheathing lies in the metal’s inherent properties. Copper is naturally toxic to many marine organisms, including the teredo worm, a voracious wood-boring mollusk responsible for significant hull damage. When submerged, copper releases ions that create a hostile environment for these pests, effectively repelling them. Additionally, the smooth surface of copper plates discouraged the attachment of fouling organisms, reducing drag and maintaining the ship’s hydrodynamic performance. Historical records show that copper-sheathed ships could maintain their speed and structural integrity for longer periods, often outperforming their untreated counterparts.

Implementing copper sheathing was not without challenges. The process required precise craftsmanship, as the plates had to be carefully fitted and nailed to the hull without compromising its structural integrity. Shipwrights used copper nails to secure the plates, ensuring a tight seal that prevented seawater from seeping between the wood and metal. However, the interaction between copper and iron fasteners in the hull could lead to galvanic corrosion, a problem later mitigated by using non-ferrous metals or insulating materials. Despite these hurdles, the benefits of copper sheathing far outweighed the drawbacks, making it a standard practice for naval and merchant vessels alike.

A notable example of copper sheathing’s success is its adoption by the British Royal Navy in the mid-18th century. After extensive trials, the Navy began sheathing its warships with copper, significantly reducing maintenance costs and improving operational readiness. Ships like HMS *Alarm* and *Irresistible* were among the first to receive this treatment, demonstrating remarkable resistance to worm damage and fouling during their voyages. The practice spread rapidly, influencing naval powers worldwide and cementing copper sheathing as a cornerstone of maritime preservation.

For modern enthusiasts or historians looking to replicate or understand this technique, it’s essential to appreciate the historical context and materials used. Copper plates were typically 1–2 mm thick and overlapped to ensure complete coverage of the hull. While copper sheathing is no longer widely used due to the advent of steel hulls and modern antifouling paints, its legacy endures as a testament to human ingenuity in overcoming the challenges of wooden shipbuilding. Studying this method not only sheds light on historical maritime practices but also highlights the timeless principle of leveraging material properties to solve complex problems.

Wood Pellets and Puppies: Safety Concerns for Three-Week-Old Canines

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Regular Maintenance: Crews constantly inspected, cleaned, and repaired ships to prevent rot and decay

The relentless battle against rot on wooden ships was fought not just with materials, but with meticulous human effort. Regular maintenance was the cornerstone of this fight, a daily ritual of inspection, cleaning, and repair that kept these vessels seaworthy for decades. Crews understood that neglect invited decay, and so they became the ship's first line of defense.

Every surface, from the towering masts to the hidden bilges, demanded scrutiny. Sailors scrutinized the wood for telltale signs of rot: discoloration, softness, or a musty odor. Even the slightest crack or splinter warranted attention, as these provided entry points for moisture, the primary catalyst for rot.

This wasn't merely a visual inspection. Experienced sailors employed a variety of tools, from sharp probes to test the wood's integrity to hammers for sounding out hollow spots. They understood the importance of catching rot early, when repairs were simpler and more effective.

Cleaning was equally crucial. Saltwater, while essential for sailing, was a corrosive enemy to wood. Crews meticulously scrubbed decks, hulls, and rigging to remove salt deposits that could accelerate deterioration. Below deck, bilges were pumped dry and scrubbed to prevent the buildup of stagnant water, a breeding ground for rot-causing fungi.

Regular repairs were the final, vital step. Damaged planks were replaced, seams were recaulked with fresh oakum and pitch, and metal fasteners were checked for corrosion. This constant cycle of inspection, cleaning, and repair was a labor-intensive process, but it was the only way to ensure the ship's longevity.

The dedication of these crews, their understanding of the wood's vulnerabilities, and their tireless efforts were the true secret to keeping these wooden giants afloat. It was a testament to human ingenuity and the power of preventative care, a legacy that continues to inspire admiration for the age of sail.

Avery Woods' Husband's Age: Unveiling the Mystery Behind Their Love Story

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$17.33

Ventilation and Drainage: Proper design allowed air circulation and water drainage, minimizing dampness and rot

Wooden ships of old were marvels of engineering, designed not just to sail the seas but to endure them. A critical aspect of their longevity was the meticulous attention to ventilation and drainage, which combated the ever-present threat of rot. These vessels were not merely built; they were crafted with an understanding of how air and water interact with wood, ensuring that dampness—the harbinger of decay—was kept at bay.

Consider the design of a ship’s hull and decks. Builders incorporated scuppers, small openings along the gunwales, to allow water to drain quickly after heavy seas or rain. These were not afterthoughts but integral features, strategically placed to prevent pooling. Below deck, limber holes were drilled into the frames, enabling water to flow into the bilge, where it could be pumped out. This system of drainage was a silent guardian, constantly working to keep the ship dry.

Ventilation was equally vital. Air circulation was facilitated through hatches, vents, and even the design of the ship’s structure itself. For instance, the spacing between planks allowed for natural airflow, preventing the stagnant, moist conditions that fungi and bacteria thrive in. Sailors also employed practical measures, like leaving hatches open during fair weather and using canvas covers to protect cargo while still permitting airflow. These methods were simple yet effective, rooted in centuries of maritime experience.

The interplay between ventilation and drainage was a delicate balance. Too much exposure to the elements could warp wood, while too little airflow invited rot. Shipwrights addressed this by using materials like oak, naturally resistant to decay, and applying protective coatings such as pitch or tar. However, even the best materials required proper design to function optimally. A well-ventilated, well-drained ship was not just a vessel; it was a living, breathing entity, maintained through constant care and foresight.

Modern shipbuilders and enthusiasts can draw lessons from these practices. For wooden boats today, ensure scuppers are clear of debris and limber holes are unclogged. Regularly inspect areas prone to moisture accumulation, like bilges and storage compartments. Incorporate breathable materials and designs that promote airflow without compromising structural integrity. By emulating the principles of ventilation and drainage from old wooden ships, we can preserve both history and functionality, ensuring these vessels continue to sail the seas for generations to come.

Unveiling Amy Wood's Age: A Comprehensive Look at Her Life

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Old wooden ships used a combination of techniques, including selecting naturally rot-resistant woods like oak, treating wood with preservatives such as tar or pitch, and ensuring proper ventilation to reduce moisture buildup.

Shipbuilders often used hardwoods like oak, teak, and cedar, which are naturally resistant to rot due to their dense grain and high levels of protective oils and tannins.

Yes, wood was often treated with substances like tar, pitch, or creosote, which acted as barriers against water and fungi. Additionally, copper sheathing was sometimes applied to hulls to deter shipworms.

Regular maintenance included cleaning, scraping, and reapplying preservatives to the hull. Ships were also careened (tilted) periodically to inspect and repair areas prone to rot, ensuring longevity despite harsh marine conditions.

![Boatlife Git Rot Kit - 4oz [1063]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/51Csyv2VbOL._AC_UY218_.jpg)