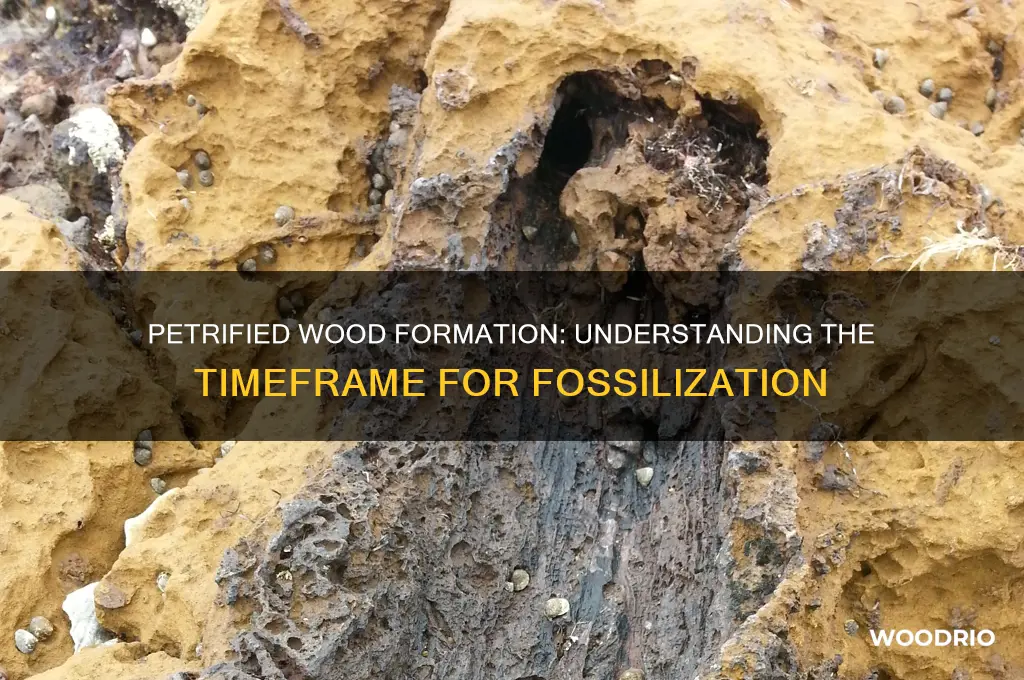

Petrification, the process by which wood transforms into stone, is a fascinating geological phenomenon that occurs over millions of years. It begins when wood becomes buried under sediment, isolating it from oxygen and decay-causing organisms. Over time, groundwater rich in minerals like silica, calcite, or pyrite seeps into the wood, gradually replacing its organic cells with these minerals while preserving its original structure. This slow mineralization process, known as permineralization, can take anywhere from 5 million to 20 million years, depending on factors such as the mineral content of the surrounding environment, temperature, and pressure. As a result, petrified wood retains the intricate details of its original form, offering a unique glimpse into Earth’s ancient past.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Process Duration | Typically takes millions of years (1-10 million years on average) |

| Key Factors | Burial in sediment, presence of minerals (silica, calcite, pyrite), lack of oxygen, consistent water flow |

| Initial Stage | Rapid burial under sediment or volcanic ash to prevent decay |

| Mineralization Time | Mineral replacement occurs gradually over thousands to millions of years |

| Preservation Quality | Depends on mineral type and environmental conditions |

| Common Minerals Involved | Silica (quartz), calcite, pyrite, opal |

| Environmental Conditions | Anaerobic (oxygen-free) environment, consistent groundwater flow |

| Fossilization vs. Petrification | Petrification specifically involves mineral replacement, not just preservation |

| Notable Locations | Petrified Forest National Park (Arizona, USA), Yellowstone National Park |

| Scientific Significance | Provides insights into ancient ecosystems and geological history |

Explore related products

$64.11 $77.99

What You'll Learn

- Factors Affecting Petrification Rate: Climate, sediment type, and wood density influence how quickly wood petrifies

- Initial Decay Process: Bacteria and fungi decompose wood before mineralization begins

- Mineralization Timeline: Silica or calcite infiltration can take thousands to millions of years

- Environmental Conditions: Wet, sediment-rich environments accelerate petrification compared to dry areas

- Preservation Stages: Wood transitions from organic to fossilized material over geological timescales

Factors Affecting Petrification Rate: Climate, sediment type, and wood density influence how quickly wood petrifies

Petrification, the process by which wood transforms into stone, is not a one-size-fits-all timeline. It’s a delicate dance of environmental factors, each playing a unique role in determining how quickly organic matter becomes mineralized. Among these, climate, sediment type, and wood density emerge as key influencers, shaping the pace of this ancient transformation. Understanding their interplay offers insight into why some petrified forests form over millennia while others take mere centuries.

Consider climate, the silent orchestrator of petrification. In arid regions, where water is scarce and evaporation rates are high, the process often accelerates. This is because silica-rich groundwater, essential for mineralization, can more readily permeate wood cells in dry conditions. For instance, the Petrified Forest National Park in Arizona, formed during the Triassic Period, benefited from a desert climate that expedited silica infiltration. Conversely, humid environments slow petrification, as excess moisture can lead to decay before mineralization occurs. A study in the *Journal of Sedimentary Research* highlights that wood buried in tropical climates may take up to 10 times longer to petrify compared to arid counterparts.

Sediment type acts as the medium through which minerals travel, dictating the efficiency of petrification. Fine-grained sediments like clay or silt provide a slower but more uniform mineralization process, as their small particles restrict water flow. Coarse sediments, such as sand or gravel, allow faster mineral transport but can result in uneven petrification. For example, wood buried in volcanic ash, rich in silica and other minerals, petrifies more rapidly due to the high mineral content and porous nature of the ash. Practical tip: If you’re attempting experimental petrification, use sediment with a high silica concentration and ensure it’s well-compacted to mimic natural conditions.

Wood density, often overlooked, is a critical internal factor. Dense hardwoods like oak or hickory, with their tightly packed cells, resist decay longer but take more time for minerals to penetrate. Softwoods like pine, with larger cell structures, decay faster but allow quicker mineral infiltration if preserved. A comparative analysis in *Paleobiology* found that dense woods can take up to 20,000 years to fully petrify, while softer woods may achieve the same in as little as 1,000 years under optimal conditions. For hobbyists, selecting wood with moderate density, such as maple or birch, strikes a balance between preservation and petrification speed.

In conclusion, petrification is a nuanced process governed by external and internal factors. Climate sets the stage, sediment type provides the pathway, and wood density determines resistance. By manipulating these variables—whether in a laboratory setting or through natural burial—one can influence the rate of petrification. While the process remains slow by human standards, understanding these factors allows for a more precise prediction of how long wood takes to become stone.

Durability of Wood Ceilings: Lifespan and Maintenance Tips Revealed

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Initial Decay Process: Bacteria and fungi decompose wood before mineralization begins

The journey of wood to petrification begins not with minerals, but with microscopic life. Bacteria and fungi, ever-present in soil and water, are the first responders to a fallen tree. These organisms, driven by their need for nutrients, secrete enzymes that break down the complex cellulose and lignin structures within the wood. This initial decay process is a race against time, as the wood's natural defenses weaken and its cellular integrity falters.

Imagine a fallen oak, its once-mighty trunk now prone on the forest floor. Within days, fungi like *Trametes versicolor* (the turkey tail fungus) and bacteria such as *Cellulomonas* species begin to colonize the surface. These decomposers secrete cellulases and ligninases, enzymes that hydrolyze the wood’s tough polymers into simpler sugars and organic acids. The wood softens, its color darkens, and its structure becomes more porous—a critical step that prepares it for the next phase of petrification. Without this biological breakdown, the wood would remain too dense and resistant to allow mineral-rich water to penetrate and replace its organic matter.

This decay process is not uniform; it depends on environmental factors like moisture, temperature, and oxygen availability. In a humid, warm environment, decomposition can occur within months, while in drier or colder conditions, it may take years. For instance, wood submerged in a swamp, where anaerobic bacteria dominate, decays more slowly but retains its shape better—a key factor in preserving the wood’s structure for later mineralization. Conversely, wood exposed to air and rain may fragment faster, reducing its chances of becoming petrified.

Practical tip: If you’re attempting to replicate petrification in a controlled setting, ensure the wood is first treated to accelerate decay. Submerge it in a solution of water and nitrogen-rich compost to encourage bacterial and fungal growth. Monitor the pH (aim for slightly acidic, around 5.5–6.0) to optimize enzymatic activity. Once the wood becomes brittle and loses 30–50% of its original weight, it’s ready for the mineralization stage.

The takeaway is clear: petrification is a two-step process, and the first step—decay—is as crucial as the second. Bacteria and fungi are not merely destroyers but facilitators, transforming wood into a substrate capable of absorbing minerals. Without their unseen labor, the wood would remain intact, resistant to the transformative power of silica, calcite, and other minerals. This initial decay is the unsung hero of petrification, a reminder that even decomposition can lead to enduring beauty.

John Wooden's Legacy: Coaching Tenure at UCLA Revealed

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Mineralization Timeline: Silica or calcite infiltration can take thousands to millions of years

Petrification, the process by which organic materials like wood transform into stone, hinges on the slow infiltration of minerals such as silica or calcite. This mineralization timeline is not a sprint but a marathon, spanning thousands to millions of years. The duration depends on environmental conditions, mineral availability, and the wood’s initial state. For instance, wood buried in sediment-rich, mineral-saturated waters, like ancient riverbeds or volcanic ash layers, petrifies faster than wood exposed to arid climates. Understanding this timeline requires a deep dive into the geological processes that govern it.

Consider the steps involved in silica infiltration, the most common pathway to petrification. First, the wood must be buried quickly to prevent decay, often in environments like swamps or volcanic ash deposits. Groundwater rich in dissolved silica then seeps into the wood’s cellular structure, replacing organic matter with quartz or chalcedony. This process, known as permineralization, occurs at a glacial pace—literally. In the Yellowstone Petrified Forest, for example, wood buried 50 million years ago during a volcanic event now displays vibrant mineral patterns, a testament to the millions of years required for complete transformation.

Calcite infiltration follows a similar timeline but often occurs in marine environments or limestone-rich areas. Here, calcium carbonate replaces the wood’s organic material, creating a fossilized structure. The difference lies in the mineral source: silica typically originates from volcanic activity or sedimentary rocks, while calcite derives from marine organisms or limestone dissolution. Both processes demand specific conditions—stable pH, consistent mineral supply, and minimal disturbance—to unfold over millennia. Practical tip: If you’re attempting experimental petrification (e.g., burying wood in mineral-rich soil), expect results only after decades, not years.

Comparing silica and calcite petrification reveals distinct outcomes. Silica-petrified wood often retains intricate cellular details, like growth rings and even tree bark, due to its finer-grained structure. Calcite-petrified wood, while equally durable, may exhibit a more crystalline appearance, with larger mineral deposits obscuring finer details. This comparison underscores why paleontologists and geologists prize silica-petrified specimens for their scientific value. For hobbyists, however, calcite-petrified wood can be equally stunning, offering a unique blend of organic and mineral beauty.

In conclusion, the mineralization timeline for petrification is a masterclass in geological patience. Whether through silica or calcite infiltration, the process demands specific conditions and vast timescales. While nature takes millions of years to perfect this transformation, understanding its mechanics allows us to appreciate the rarity and beauty of petrified wood. For those inspired to experiment, remember: petrification is not a quick craft but a testament to time’s power.

Wood Life Copper Coat Durability: Longevity and Maintenance Tips

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$6.99

Environmental Conditions: Wet, sediment-rich environments accelerate petrification compared to dry areas

Petrification, the process by which wood transforms into stone, is not a uniform phenomenon. The speed at which this occurs depends heavily on the environment in which the wood is buried. Wet, sediment-rich environments act as catalysts, significantly accelerating the petrification process compared to dry areas. This is due to the unique combination of factors these environments provide, which are essential for the mineralization of wood.

In wet environments, groundwater rich in dissolved minerals like silica, calcite, and pyrite constantly flows through the buried wood. This mineral-laden water acts as a delivery system, depositing minerals into the wood's cellular structure. Over time, these minerals replace the organic material cell by cell, gradually turning the wood into a stone replica. Sediment-rich environments further enhance this process by providing a protective layer around the wood, shielding it from oxygen and slowing decay. This anaerobic condition is crucial, as oxygen promotes the activity of microorganisms that break down wood.

Imagine a fallen tree in a dry, arid desert. Exposed to the elements, it will likely succumb to weathering and decay, its organic matter returning to the soil. Now picture a tree submerged in a muddy riverbed, buried under layers of silt and clay. Here, deprived of oxygen and bathed in mineral-rich water, the tree has a much higher chance of undergoing petrification. The sediment acts as a natural preservative, slowing decay and providing a stable environment for mineralization.

While the exact timeframe for petrification varies widely, ranging from thousands to millions of years, the presence of water and sediment can significantly shorten this process. Studies suggest that wood buried in wet, sediment-rich environments can begin to show signs of mineralization within a few hundred years, whereas wood in dry environments may take significantly longer, if it petrifies at all.

Understanding the role of environmental conditions in petrification has practical applications. Paleontologists and geologists can use this knowledge to identify potential fossil sites, focusing their efforts on areas with the right combination of water and sediment. Additionally, this understanding can inform conservation efforts, helping to protect environments that are conducive to the formation of these fascinating natural wonders.

Hiking Lincoln Woods Trail: Time Estimates and Tips for Success

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Preservation Stages: Wood transitions from organic to fossilized material over geological timescales

Petrification is a geological process that transforms organic wood into fossilized material, preserving it for millions of years. This transformation occurs in distinct stages, each requiring specific environmental conditions and varying in duration. Understanding these stages provides insight into the remarkable journey from living tree to stone-like fossil.

Stage 1: Rapid Burial and Anaerobic Conditions

The first critical step in petrification is the rapid burial of wood, typically in sediment such as mud, volcanic ash, or sand. This burial shields the wood from oxygen and decomposing organisms, slowing decay. Without oxygen, anaerobic bacteria can only partially break down the organic material, preserving the wood’s cellular structure. This stage can last from a few years to several centuries, depending on the burial environment. For example, wood buried in a riverbed might be protected within decades, while exposure to surface conditions could delay burial significantly.

Stage 2: Mineral Infiltration and Cell Replacement

Once buried, groundwater rich in minerals like silica, calcite, or pyrite seeps into the wood’s cellular structure. Over time, these minerals precipitate, filling the voids left by decaying organic matter. This process, known as permineralization, gradually replaces the wood’s original cellulose and lignin with stone. The rate of mineral infiltration varies widely, from thousands to millions of years, influenced by factors like mineral concentration, temperature, and pressure. For instance, silica-rich environments, such as those near volcanic activity, can accelerate petrification, sometimes completing the process in as little as 10,000 years.

Stage 3: Complete Fossilization and Exposure

The final stage involves the complete replacement of organic material with minerals, transforming the wood into a durable fossil. This stage is the longest, often spanning millions of years, as it requires sustained geological stability. Once fossilized, the petrified wood may remain buried until erosion exposes it. Practical tip: Collectors and geologists often find petrified wood in areas with significant sedimentary rock exposure, such as arid regions or riverbeds, where erosion rates are high.

Comparative Perspective: Natural vs. Accelerated Processes

While natural petrification takes millions of years, scientists have experimented with accelerated methods, such as exposing wood to high-pressure mineral solutions in laboratory settings. These techniques can reduce the process to mere months or years, though the results are not identical to naturally petrified wood. This comparison highlights the balance between geological patience and human ingenuity, offering both scientific and artistic applications for preserved wood.

In summary, the transition of wood from organic to fossilized material is a multi-stage process shaped by burial, mineralization, and exposure. Each stage demands specific conditions and timeframes, underscoring the complexity of petrification. Whether studying natural fossils or creating artificial ones, understanding these preservation stages deepens our appreciation for Earth’s geological history.

Mineral Oil on Wood: Durability, Lifespan, and Reapplication Tips

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The process of petrification typically takes millions of years, often ranging from 5 to 50 million years, depending on environmental conditions.

Key factors include the presence of mineral-rich water, consistent burial conditions, temperature, pressure, and the type of wood. Faster petrification occurs in environments with high mineral content and stable conditions.

While rare, wood can show early stages of petrification in as little as 10,000 years under ideal conditions, but full petrification still requires millions of years.

Yes, denser woods with more lignin, like conifers, tend to petrify more easily and quickly compared to softer woods, as they better resist decay and retain structure during mineralization.