Wood rot from water exposure is a gradual process influenced by several factors, including the type of wood, moisture levels, temperature, and the presence of fungi. Softwoods, like pine, typically decay faster than hardwoods, such as oak, due to their lower density and natural resistance. In consistently wet conditions, wood can begin to show signs of rot within a few months, with significant deterioration occurring within one to two years. However, in environments with intermittent moisture or proper ventilation, wood may take five years or more to rot. Preventive measures, such as sealing or treating the wood, can significantly slow this process, highlighting the importance of maintenance in prolonging wood’s lifespan.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Type of Wood | Hardwoods (e.g., oak, teak) last longer than softwoods (e.g., pine). |

| Moisture Content | Constant exposure to water accelerates rot (weeks to months). |

| Oxygen Availability | Anaerobic conditions (lack of oxygen) slow down rot. |

| Temperature | Warmer temperatures (20-35°C) speed up decomposition. |

| Presence of Fungi/Bacteria | Fungi (e.g., brown rot, white rot) and bacteria accelerate rot. |

| Wood Treatment | Pressure-treated wood lasts 20+ years; untreated wood rots faster. |

| Environmental Exposure | Direct contact with soil or water shortens lifespan (1-5 years). |

| Wood Density | Higher density woods (e.g., cedar) resist rot better. |

| pH Level of Environment | Acidic conditions (pH < 5) can accelerate rot. |

| Insect Activity | Termites and beetles speed up decay. |

| Typical Lifespan in Water | Untreated wood: 1-5 years; treated wood: 10-40+ years. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Factors affecting wood rot speed

Wood exposed to water doesn't rot at a fixed rate. The speed of decay is a complex dance influenced by several key factors. Understanding these factors is crucial for anyone working with wood in damp environments, from builders to homeowners.

Let's delve into the specifics.

Moisture Content: The primary driver of wood rot is moisture. Wood needs to reach a moisture content of around 20% or higher for fungi, the primary agents of decay, to thrive. Constant exposure to water, like in a leaky roof or poorly drained soil, creates ideal conditions for rot. Conversely, wood kept consistently dry, below 15% moisture content, is highly resistant to decay.

Utilize moisture meters to monitor wood moisture levels, especially in critical areas like foundations and exterior structures.

Wood Species: Not all wood is created equal when it comes to rot resistance. Some species, like cedar, redwood, and cypress, possess natural oils and resins that act as built-in preservatives, slowing down decay. Others, like pine and fir, are more susceptible and require additional protection. When choosing wood for damp environments, prioritize naturally rot-resistant species or opt for pressure-treated wood, which has been chemically treated to resist decay.

Pro Tip: Even rot-resistant wood benefits from proper sealing and maintenance to maximize its lifespan.

Temperature and Oxygen: Fungi, the culprits behind wood rot, thrive in warm, oxygen-rich environments. Ideal temperatures for fungal growth range from 70°F to 90°F (21°C to 32°C). In colder climates, rot progresses more slowly, while in hot, humid regions, it accelerates. Limiting oxygen exposure by sealing wood surfaces can also hinder fungal growth. Consider using breathable sealants that allow moisture to escape while preventing water infiltration.

Ventilation and Sunlight: Proper ventilation is crucial for preventing moisture buildup, a key factor in rot. Ensure adequate airflow around wood structures, especially in enclosed spaces like crawl spaces and attics. Sunlight acts as a natural disinfectant, inhibiting fungal growth. Whenever possible, expose wood to sunlight to help keep it dry and discourage rot.

Caution: While sunlight can be beneficial, prolonged exposure to UV rays can also degrade wood over time. Striking a balance is key.

How Long Do 3-Inch Nails Stay Secure in Wood Before Loosening?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Types of wood resistance levels

Wood's resistance to rot from water exposure varies dramatically based on species, with some lasting decades while others succumb within months. This disparity hinges on natural oils, resins, and density, which act as barriers against moisture infiltration and fungal decay. For instance, teak and cedar contain high levels of protective oils, making them exceptionally resistant, while pine and spruce lack these defenses and deteriorate rapidly without treatment. Understanding these inherent properties is crucial for selecting wood suited to wet environments, such as outdoor furniture or marine applications.

To maximize wood longevity in water-prone areas, prioritize hardwoods like white oak or black locust, which possess dense cell structures that naturally repel moisture. Softwoods, though less resistant, can be treated with preservatives like copper azole or alkaline copper quaternary (ACQ) to extend their lifespan. For example, pressure-treated pine, infused with these chemicals, can endure up to 40 years in ground contact, compared to untreated pine’s mere 5–10 years. Always follow manufacturer guidelines for application rates—typically 0.25 to 0.40 pounds of preservative per cubic foot of wood—to ensure effectiveness without compromising structural integrity.

When comparing resistance levels, consider not just species but also environmental factors. Tropical hardwoods like ipe and cumaru thrive in humid climates due to their dense grain and natural tannins, while even rot-resistant woods like redwood may falter in stagnant water conditions. For projects like decks or docks, combine resistant species with proper design—elevate structures to allow airflow, use stainless steel fasteners to prevent corrosion, and apply water-repellent sealants annually. These measures mitigate risks and optimize wood performance in wet settings.

A practical takeaway is to match wood type to its intended use. For instance, use naturally resistant cypress for garden beds, treated fir for fence posts, and teak for boat decking. Regular maintenance, such as reapplying preservatives every 2–3 years and inspecting for cracks or splinters, further safeguards against rot. By aligning wood selection with its resistance profile and environmental demands, you ensure durability and reduce long-term replacement costs. This strategic approach transforms wood from a vulnerable material into a resilient asset, even in water-exposed conditions.

Foraging for Wood in The Long Dark: Essential Survival Tips

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$4199.99

Role of moisture content in decay

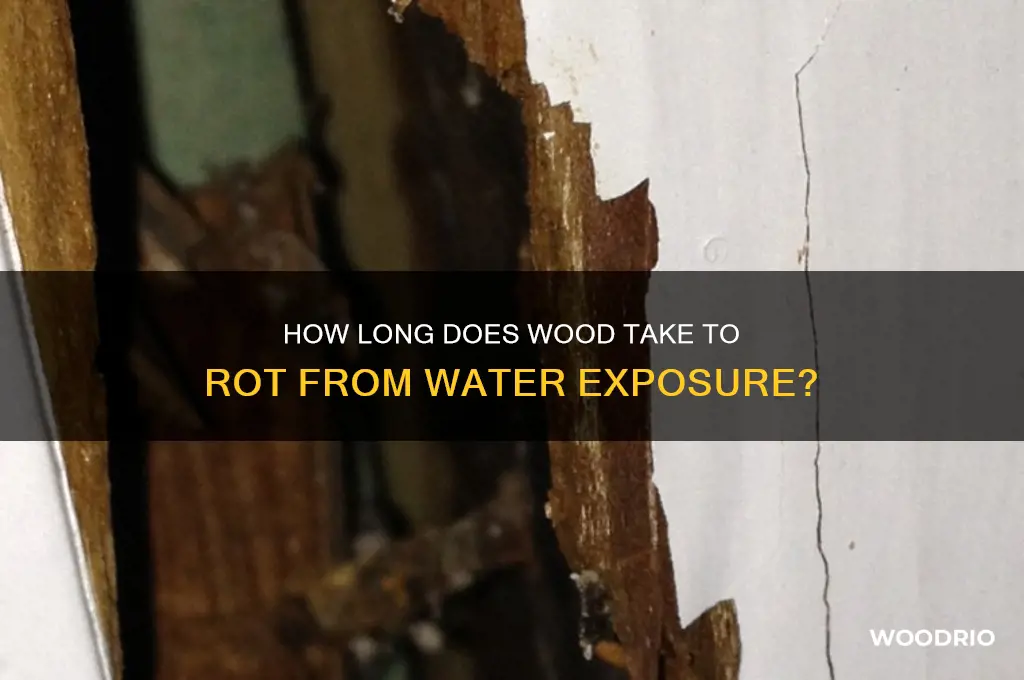

Wood decay is a complex process influenced by various factors, but moisture content stands out as a critical determinant of how quickly wood deteriorates. When wood absorbs water, its moisture content rises, creating an environment conducive to fungal growth—the primary agent of decay. Fungi require a moisture content above 20% to thrive, making this threshold a pivotal point in the decay process. Below this level, wood remains relatively resistant to fungal attack, but as moisture content increases, the risk of decay escalates exponentially.

Consider the practical implications of moisture management in wood preservation. For outdoor structures like decks or fences, maintaining moisture content below 20% is essential. This can be achieved through proper sealing, regular maintenance, and strategic design to minimize water retention. For instance, using pressure-treated wood, which has been infused with preservatives, can significantly delay decay by reducing water absorption. Additionally, ensuring adequate ventilation and drainage around wooden structures prevents water accumulation, further safeguarding against excessive moisture.

The relationship between moisture content and decay is not linear but rather a delicate balance. While some moisture is necessary for wood to remain pliable and structurally sound, excessive moisture accelerates degradation. In humid climates, wood can reach critical moisture levels more rapidly, often within months, whereas in drier regions, it may take years for decay to become apparent. This variability underscores the importance of context-specific strategies for moisture control, such as using dehumidifiers in enclosed spaces or applying water-repellent coatings in high-humidity areas.

A comparative analysis of wood species reveals that density and natural oils also play a role in moisture resistance. Hardwoods like teak and cedar, which contain natural resins, are inherently more resistant to water absorption and decay. In contrast, softwoods like pine are more susceptible and require additional treatments to enhance durability. For example, applying a borate solution to pine can inhibit fungal growth by reducing wood’s moisture absorption capacity, effectively extending its lifespan in wet conditions.

In conclusion, managing moisture content is paramount in preventing wood decay. By understanding the critical threshold of 20% moisture content and implementing targeted strategies such as proper sealing, species selection, and environmental control, one can significantly prolong the life of wooden structures. Whether through preventive measures or remedial treatments, the goal remains the same: to keep moisture at bay and preserve the integrity of wood in the face of water-induced decay.

Drying Time for Pressure Treated Wood: What to Expect

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Impact of environmental conditions on rot

Wood rot is a complex process influenced heavily by environmental conditions, each playing a unique role in accelerating or slowing decay. Moisture, temperature, oxygen availability, and biological activity collectively determine how quickly wood succumbs to rot. For instance, wood submerged in water with limited oxygen access may develop anaerobic bacteria, which decompose cellulose at a slower rate compared to aerobic fungi thriving in damp, well-ventilated environments. Understanding these interactions is crucial for predicting and managing wood longevity in various settings.

Consider the impact of moisture content, the primary catalyst for rot. Wood with a moisture level above 20% becomes susceptible to fungal growth, while levels exceeding 30% create ideal conditions for rapid decay. In tropical climates, where humidity often surpasses 80%, untreated wood structures may deteriorate within 5–10 years. Conversely, in arid regions with humidity below 30%, wood can remain intact for decades, even when exposed to occasional water contact. Practical tip: To mitigate moisture-induced rot, ensure wood is treated with preservatives like copper azole or borates, and maintain a moisture content below 19% through proper ventilation and sealing.

Temperature acts as a silent moderator, influencing both moisture retention and microbial activity. In temperate zones with temperatures ranging between 50°F and 90°F, fungi proliferate most actively, doubling their metabolic rate for every 18°F increase within this range. Cold environments, such as those below 40°F, significantly slow decay by inhibiting microbial growth, while extreme heat above 100°F can desiccate wood, temporarily halting rot but weakening its structural integrity over time. For outdoor applications, select wood species like cedar or redwood, naturally resistant to temperature fluctuations, and apply thermal-barrier coatings to minimize heat absorption.

Oxygen availability introduces another layer of complexity, particularly in waterlogged environments. Submerged wood in stagnant water, where oxygen is scarce, often develops anaerobic bacteria that decompose lignin at a glacial pace, extending the wood’s lifespan to 50 years or more. In contrast, wood exposed to alternating wet and dry cycles in oxygen-rich environments experiences accelerated decay due to repeated fungal colonization. To combat this, elevate wooden structures on piers or use non-porous barriers to limit water saturation while ensuring adequate airflow around the material.

Finally, biological factors, such as insect infestations and microbial diversity, exacerbate rot under specific environmental conditions. Termites, for example, thrive in warm, humid climates and can reduce a wooden beam’s lifespan by 50% within 3 years. Similarly, acid rain in industrial areas lowers wood pH, making it more susceptible to decay by softening its protective lignin layer. Regular inspections and proactive treatments, such as insecticidal sprays or pH-neutralizing washes, are essential for preserving wood in biologically hostile environments. By addressing these environmental variables holistically, one can significantly extend the functional life of wooden materials.

Tanalised Wood Durability: Lifespan, Maintenance, and Longevity Explained

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Preventive measures to slow wood rot

Wood exposed to moisture is a ticking clock, with rot setting in as quickly as a few months in damp, warm conditions. To halt this countdown, start by eliminating the enemy: water. Ensure proper drainage around wooden structures, redirecting gutters and downspouts away from foundations. For decks or fences, a slight slope of 1/4 inch per foot will encourage runoff, preventing water from pooling. Regularly inspect and clean out gutters to avoid overflow, which can saturate nearby wood.

Once water management is in place, focus on protective barriers. Apply a high-quality, water-repellent sealant or stain every 2–3 years, depending on exposure. For pressure-treated wood, use a product specifically designed for its unique properties. In high-moisture areas, consider marine-grade varnishes or epoxy coatings, which form a harder, more durable shield. For added protection, incorporate breathable membranes like housewrap behind wooden siding to prevent moisture buildup while allowing vapor escape.

Biological threats—fungi and insects—accelerate rot, so preemptive treatment is critical. Use borate-based wood preservatives, which penetrate deep into the material to kill existing pests and prevent new infestations. Mix 1 gallon of borate solution per 100 square feet of wood, applying it with a sprayer or brush until the wood is thoroughly saturated. For new constructions, opt for naturally rot-resistant species like cedar, redwood, or teak, though even these benefit from periodic treatment.

Finally, design with longevity in mind. Incorporate ventilation gaps in wooden structures to allow air circulation, which dries out trapped moisture. For ground-contact applications, use concrete or metal bases to elevate wood, reducing direct exposure to soil moisture. In humid climates, install vapor barriers beneath wooden floors or within wall cavities to block rising dampness. By combining these strategies, you can significantly extend the lifespan of wood, delaying rot by decades rather than years.

Crafting a Wooden Bow: Time Investment and Skill Required

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Wood can begin to rot within 6 months to 2 years when consistently exposed to moisture, depending on the type of wood, environmental conditions, and the presence of fungi or insects.

No, different types of wood rot at varying rates. Softwoods like pine rot faster, while hardwoods like teak or cedar are more resistant due to natural oils and density.

Yes, wood rot can be prevented or slowed by treating wood with preservatives, sealants, or water-repellent coatings, ensuring proper ventilation, and minimizing prolonged exposure to moisture.

Warmer temperatures accelerate wood rot by promoting fungal growth and bacterial activity, while colder temperatures slow down the process but do not completely stop it.

Signs of wood rot include discoloration, softness or sponginess, cracking, a musty odor, and the presence of mold or fungi on the surface.