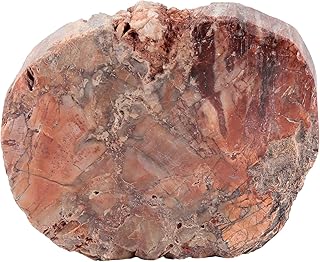

Petrified wood, a fascinating natural phenomenon, is the result of a slow and intricate process where organic wood is transformed into stone over millions of years. The age of wood required for petrification is a subject of geological interest, as it typically takes at least 10 million years for wood to fully petrify under specific conditions. This process involves the wood being buried under sediment, protected from decay, and gradually infiltrated by mineral-rich water, which replaces the organic material with minerals like silica, calcite, or pyrite. While younger wood can undergo partial fossilization, true petrification demands an extensive timescale, often spanning tens of millions of years, making it a testament to Earth’s geological history.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Minimum Age Requirement | Typically 10,000 to 20,000 years, though some processes can take longer. |

| Optimal Conditions | Burial in sediment with high mineral content (e.g., silica, calcite). |

| Process Duration | Can range from thousands to millions of years, depending on conditions. |

| Key Factors Influencing Petrification | Lack of oxygen, presence of minerals, stable environmental conditions. |

| Resulting Material | Fossilized wood (petrified wood) with preserved cellular structure. |

| Common Locations | Areas with volcanic ash or sedimentary deposits (e.g., Petrified Forest National Park, USA). |

| Scientific Term | Permineralization (replacement of organic material with minerals). |

| Age Verification Method | Radiometric dating (e.g., carbon-14, uranium-lead dating). |

Explore related products

$39.5

What You'll Learn

- Petrification Process Basics: How minerals replace organic wood material over time, turning it to stone

- Timeframe for Petrification: Typically takes thousands to millions of years under specific conditions

- Required Conditions: Needs burial in sediment, water with minerals, and lack of oxygen

- Wood Type Influence: Softwoods and hardwoods petrify differently due to cellular structure

- Preservation vs. Petrification: Not all old wood becomes petrified; preservation varies

Petrification Process Basics: How minerals replace organic wood material over time, turning it to stone

Petrified wood is a fossil in which the organic materials have been replaced by minerals, most commonly silica, while retaining the original structure of the wood. This process, known as permineralization, transforms wood into stone over millions of years. The age of wood required for petrification varies, but it typically takes at least 10,000 years, with most specimens dating back 20 to 250 million years. The key to petrification is not just time but the specific environmental conditions that allow minerals to infiltrate and replace the wood’s cellular structure.

The petrification process begins when wood becomes buried under sediment, such as volcanic ash, mud, or sand, which shields it from decay. Groundwater rich in dissolved minerals like silica, calcite, or pyrite then seeps into the wood, filling its pores and cavities. Over time, these minerals precipitate out of the water, crystallizing within the wood’s cell walls and eventually replacing the organic material entirely. This gradual replacement preserves the wood’s original texture, growth rings, and even cellular details, creating a stone replica of the once-living tissue.

One of the most critical factors in petrification is the absence of oxygen, which prevents decay. Wood buried in anaerobic environments, such as deep riverbeds or volcanic deposits, is more likely to petrify. For example, the Petrified Forest National Park in Arizona boasts some of the world’s most stunning petrified wood, formed over 225 million years ago when the region was a lush, tropical environment. The wood was buried by volcanic ash and sediment, and silica-rich groundwater transformed it into quartz-based stone, often with vibrant colors due to trace minerals like iron and manganese.

To understand the petrification process, consider it as a slow, mineral-driven alchemy. Imagine a tree falling into a river and being quickly buried by sediment. Over centuries, groundwater carrying dissolved silica infiltrates the wood, depositing quartz crystals in its cells. As the organic material degrades, it is replaced molecule by molecule, leaving behind a stone fossil. This process requires not only time but also a stable geological environment where the wood remains undisturbed and mineral-rich water is consistently present.

Practical observation of petrified wood reveals its durability and beauty, making it a prized material for collectors and artisans. However, creating petrified wood artificially is challenging, though experiments have accelerated the process using high-pressure, mineral-rich solutions. For natural petrification, patience is key—the wood must remain buried and mineral-exposed for millennia. Whether found in ancient forests or laboratory settings, the petrification process highlights the remarkable interplay between organic matter and geological forces, turning wood into a timeless stone artifact.

Mastering the Art of Aging Wood: Techniques for a Rotten, Weathered Look

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Timeframe for Petrification: Typically takes thousands to millions of years under specific conditions

Petrification, the process by which organic materials like wood turn into stone, is not an overnight affair. It demands an extraordinary amount of time, typically spanning thousands to millions of years. This transformation occurs under highly specific conditions, where wood is buried in sediment rich in minerals and shielded from oxygen, allowing silica and other minerals to slowly infiltrate its cellular structure. The result is a fossilized replica of the original wood, often retaining intricate details like growth rings and even cellular patterns.

Consider the petrified forests found in Arizona, USA, where ancient trees from the Triassic period, over 225 million years old, have been preserved in stunning detail. These specimens illustrate the immense timescale required for petrification. The process begins with rapid burial, often due to volcanic ash, mudslides, or waterlogged environments, which prevents decay. Over millennia, groundwater saturated with dissolved minerals seeps into the wood, replacing organic matter with minerals like quartz, calcite, or pyrite, cell by cell. This gradual mineralization is why petrified wood often exhibits a crystalline luster and vibrant colors, depending on the minerals present.

While the timeframe for petrification is vast, it’s not uniform. Factors like temperature, mineral concentration, and the type of wood influence the speed of the process. For instance, softer woods with larger cell structures may petrify more quickly than denser hardwoods, though both require immense periods of time. Scientists estimate that under optimal conditions—such as consistent mineral-rich water flow and stable environmental conditions—petrification can occur in as little as 10,000 years. However, most examples, like those in Argentina’s Patagonia or China’s Huangshan Mountains, date back millions of years, underscoring the rarity of the process.

For those fascinated by petrified wood, understanding its timeline offers a deeper appreciation for these geological treasures. Collectors and enthusiasts should note that while artificial petrification can be accelerated in laboratory settings using high-pressure mineral solutions, it still takes months to years to achieve partial results. Natural petrified wood, however, is irreplaceable, a testament to Earth’s patient craftsmanship. When handling or displaying these specimens, avoid exposure to harsh chemicals or extreme temperatures, as even stone can degrade over time. Instead, preserve them as reminders of the slow, relentless march of geological history.

Reviving Old Outdoor Wood: Creative Recycling Tips for Sustainable Projects

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Required Conditions: Needs burial in sediment, water with minerals, and lack of oxygen

Petrification, the process that transforms wood into stone, demands a precise set of environmental conditions. Chief among these is burial in sediment. This step is crucial because it shields the wood from decay-inducing elements like oxygen and sunlight. Without this protective layer, microorganisms would swiftly decompose the organic material, leaving nothing behind to fossilize. Sediment acts as a natural barrier, preserving the wood’s structure long enough for mineralization to occur. Think of it as nature’s time capsule, sealing the wood away from the destructive forces of the surface world.

Once buried, the presence of water rich in minerals becomes the next critical factor. Groundwater percolating through the sediment carries dissolved minerals like silica, calcite, and pyrite. Over time, these minerals seep into the wood’s cellular structure, gradually replacing the organic matter with inorganic compounds. This process, known as permineralization, is slow and requires a consistent supply of mineral-laden water. For example, petrified forests like those in Arizona formed over millions of years in environments where volcanic ash provided abundant silica, accelerating the transformation. Without this mineral-rich water, the wood would simply decay, leaving no trace of its existence.

Equally important is the absence of oxygen, which stifles the activity of decomposing organisms. In an oxygen-depleted environment, bacteria and fungi that typically break down wood are unable to thrive. This lack of oxygen, often achieved through deep burial or submersion in waterlogged sediment, ensures the wood remains intact long enough for minerals to infiltrate its structure. Imagine a log submerged in a swamp: if exposed to air, it would rot away, but buried in anaerobic mud, it stands a chance of becoming petrified. This condition underscores the delicate balance required for fossilization.

Practical considerations for understanding petrification include examining environments where these conditions naturally occur. Swamps, river deltas, and volcanic ash deposits are prime locations for petrification because they provide sediment, mineral-rich water, and oxygen-poor settings. For instance, the famous petrified wood of the Yellowstone region formed in a prehistoric forest buried by volcanic ash and mudflows. To observe this process firsthand, visit sites like Petrified Forest National Park, where millions of years of geological history are preserved in stunning detail. By studying these environments, we gain insight into the specific conditions that turn wood into stone.

In summary, petrification is not a matter of age alone but a product of specific environmental conditions. Burial in sediment, exposure to mineral-rich water, and an oxygen-free environment are the key ingredients. These factors work in tandem over vast timescales, transforming organic wood into a durable mineral replica. Understanding these requirements not only sheds light on Earth’s geological history but also highlights the intricate interplay between biology and geology in shaping our planet’s fossil record.

Mastering Drill Techniques: Effortlessly Penetrating Aged Wood with Precision

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$45.99

Wood Type Influence: Softwoods and hardwoods petrify differently due to cellular structure

Petrification, the process by which wood transforms into stone, is not a uniform phenomenon. The cellular structure of softwoods and hardwoods plays a pivotal role in how they petrify, influencing both the timeline and the final appearance of the fossilized wood. Softwoods, such as pine and spruce, have simpler cell structures with larger, resin-filled canals. This resin, rich in organic compounds, can accelerate the petrification process by providing a natural source of minerals. Hardwoods, like oak and maple, possess denser, more complex cell walls with smaller vessels. Their structure often results in a slower petrification process but can yield more intricate, detailed fossils due to the preservation of finer cellular details.

To understand the petrification timeline, consider the following: softwoods, with their resinous content, can begin the petrification process within 1,000 to 10,000 years under ideal conditions. The resin acts as a natural preservative, attracting minerals like silica and calcite from groundwater. Hardwoods, however, typically require 10,000 to 100,000 years to fully petrify due to their denser structure, which slows the infiltration of minerals. For example, a pine log buried in a mineral-rich volcanic ash deposit might show early stages of petrification within a millennium, while an oak log in the same environment could take ten times longer to achieve a similar state.

Practical considerations for identifying petrified wood types include examining the fossil’s texture and color. Softwoods often exhibit a more uniform, glass-like appearance due to their resin-dominated structure, while hardwoods retain visible growth rings and grain patterns. A simple field test involves scratching the surface: softwood fossils tend to be harder and more resistant to scratching due to their silica-rich composition, whereas hardwood fossils may show slight indentations under pressure.

For enthusiasts and collectors, understanding these differences can enhance the appreciation of petrified wood. Softwood fossils are ideal for showcasing the rapid transformation of organic material into stone, while hardwood fossils offer a glimpse into the preservation of ancient botanical structures. When acquiring petrified wood, inquire about its origin and estimated age to better understand its unique journey. For instance, a piece of petrified pine from Arizona’s Petrified Forest National Park might be 225 million years old, while a hardwood fossil from the same region could date back to the Triassic period, offering a tangible connection to Earth’s distant past.

In conclusion, the cellular structure of softwoods and hardwoods dictates their petrification timeline and final characteristics. Softwoods, with their resinous canals, petrify faster and produce smoother fossils, while hardwoods, with their dense cell walls, take longer but preserve intricate details. By recognizing these differences, one can deepen their understanding of the petrification process and better appreciate the geological and botanical stories embedded in each fossilized piece of wood.

Revive Old Wood: Simple Steps to Achieve a Shiny Finish

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Preservation vs. Petrification: Not all old wood becomes petrified; preservation varies

Petrified wood, a mesmerizing fossilized remnant of ancient forests, captivates with its stone-like beauty. But not all aged timber undergoes this transformation. Preservation, a broader term, encompasses various processes that shield wood from decay, while petrification is a specific, mineral-driven metamorphosis. Understanding this distinction is crucial for appreciating the diverse fates of wood over millennia.

Wood's journey through time is dictated by its environment. In oxygen-depleted settings like bogs or deep lake beds, anaerobic conditions stifle decay, preserving wood for centuries, even millennia. The Somerset Levels in England, for instance, have yielded wooden trackways dating back 6,000 years, remarkably intact due to waterlogging. This preservation, however, is not petrification; the wood retains its organic structure, vulnerable to decay if exposed to air.

Petrification, a far rarer process, demands specific conditions. Buried wood, deprived of oxygen and immersed in mineral-rich groundwater, undergoes a slow, alchemical change. Over thousands, even millions of years, silica, calcite, or pyrite seep into the wood's cellular structure, replacing organic matter with minerals. This process, known as permineralization, transforms wood into a stone replica, preserving intricate details like growth rings and cellular patterns. The Petrified Forest National Park in Arizona showcases this phenomenon, with 225-million-year-old trees transformed into vibrant quartz sculptures.

The age required for petrification is not a fixed number but a range, dependent on mineral availability and environmental stability. While some specimens petrify within a few thousand years, others, like the 360-million-year-old petrified wood found in Scotland, testify to the process's potential for extreme longevity. Preservation, on the other hand, can occur within decades, as seen in shipwrecks preserved in cold, anoxic waters.

Distinguishing preservation from petrification is essential for conservation efforts. Preserved wood, though ancient, remains susceptible to deterioration upon exposure. Petrified wood, however, is virtually indestructible, a testament to the Earth's transformative power. Recognizing these differences allows us to appreciate the diverse ways wood endures, from the fragile relics of bogs to the stone sentinels of ancient forests.

Reclaimed Barn Wood: A Profitable Business for Companies?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Petrified wood typically takes millions of years to form, with most specimens dating back to the Triassic period, around 225 to 200 million years ago.

While rare, partial petrification can occur in a few thousand years under ideal conditions, but complete petrification usually requires much longer, often millions of years.

Petrification requires the wood to be buried in sediment rich in minerals, protected from decay, and exposed to groundwater with dissolved minerals over an extended period.

Yes, petrified wood is a type of fossil. It forms when organic material is replaced by minerals, preserving the original structure of the wood in stone.