Drilling through old wood requires careful consideration to avoid damaging the material or your tools. Aged wood can be brittle, prone to splitting, and may contain hidden nails or screws, making it essential to approach the task with precision. Start by inspecting the wood for any signs of decay, knots, or existing hardware, and use a sharp, appropriately sized drill bit to minimize tearing. Applying gentle, consistent pressure and using a slow drilling speed can help prevent splintering, while pre-drilling pilot holes is highly recommended to guide the bit and reduce the risk of cracking. Additionally, using a backing board behind the wood can provide support and prevent blowout on the exit side, ensuring a clean and successful hole.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

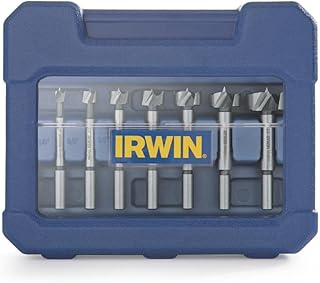

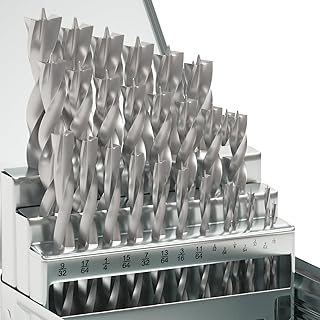

| Drill Bit Type | Use a brad-point bit or auger bit for clean, precise holes. For larger holes, a forstner bit is ideal. |

| Drill Bit Material | Opt for high-speed steel (HSS) or cobalt bits for durability when drilling through hard, old wood. |

| Drill Speed | Use low to medium speed to prevent overheating and splintering. |

| Pilot Hole | Always pre-drill a pilot hole to guide the bit and reduce splitting, especially in brittle old wood. |

| Clamping | Secure the wood firmly with clamps to prevent movement and ensure accuracy. |

| Backing Board | Place a scrap piece of wood behind the workpiece to prevent tear-out on the exit side. |

| Marking | Use a center punch or awl to mark the drilling spot for precision. |

| Lubrication | Apply beeswax or drill lubricant to reduce friction and heat buildup. |

| Pressure | Apply steady, consistent pressure without forcing the drill to avoid breaking the bit or wood. |

| Sharpness | Ensure the drill bit is sharp to achieve clean cuts and minimize splintering. |

| Grain Direction | Drill perpendicular to the grain to reduce the risk of splitting. |

| Hole Size | Start with a smaller bit and gradually increase size if needed for larger holes. |

| Old Wood Condition | Inspect for rot, cracks, or weakness and adjust drilling technique accordingly. |

| Safety Gear | Wear safety glasses and dust mask to protect from wood debris and dust. |

Explore related products

$14.79 $18.98

What You'll Learn

Using the Right Drill Bit

Drilling through old wood requires precision and the right tools. The first step is selecting the appropriate drill bit, as using the wrong one can lead to splintering, cracking, or excessive wear. Old wood, often denser and more brittle due to age and drying, demands a bit designed to handle its unique characteristics. A high-quality, sharp brad-point bit is ideal for clean entry and exit holes, minimizing tear-out. For larger holes, a Forstner bit provides superior control and a smoother finish, especially in hardwoods like oak or maple commonly found in antique furniture or structures.

Consider the material’s condition before choosing your bit. Old wood may contain hidden nails, screws, or knots, which can dull or break a standard bit. A titanium-coated or cobalt bit offers increased durability and heat resistance, reducing the risk of damage when encountering these obstacles. For softer, more deteriorated wood, a spade bit with a sharp cutting edge can be effective, but use caution to avoid excessive force, which can cause the wood to crumble. Always start with a pilot hole, especially in fragile or valuable pieces, to guide the bit and prevent splitting.

The angle and speed of drilling also depend on the bit you choose. A twist bit, while versatile, can wander in old wood due to its lack of a centering point. For better accuracy, opt for a brad-point bit and drill at a slower speed (around 1,000 RPM) to maintain control and reduce heat buildup. When drilling deep holes, periodically withdraw the bit to clear wood chips, as they can increase friction and cause the bit to bind. This technique prolongs bit life and ensures a cleaner hole.

Finally, test your chosen bit on a scrap piece of similar wood before starting your project. This allows you to assess the bit’s performance and adjust your technique if needed. For example, if the bit causes excessive splintering, try reducing the speed or applying masking tape around the drill area to minimize tear-out. By investing time in selecting and testing the right bit, you’ll achieve professional results while preserving the integrity of the old wood.

Eclipse Hydrangea Blooming Secrets: Old Wood vs. New Wood

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Marking and Aligning Holes

Drilling through old wood requires precision, especially when aligning holes for structural integrity or aesthetic appeal. Marking your drill points accurately is the first step to success. Begin by using a sharp pencil or marking tool to indicate the center of the hole. For larger projects, consider a center punch to create a small indentation, ensuring your drill bit doesn’t wander. This simple act of marking transforms guesswork into a controlled process, reducing the risk of splitting the wood or misalignment.

Alignment is critical, particularly when drilling through multiple layers or joining pieces of old wood. A common technique is to use a straightedge or ruler to draw a line connecting multiple hole marks, ensuring they’re in perfect sequence. For vertical alignment, a plumb bob or laser level can guide your markings, especially in larger structures like beams or furniture. If you’re working with reclaimed wood, which often has uneven surfaces, clamp a scrap piece of straight wood as a guide to keep your drill perpendicular to the surface.

Persuasive precision tools like drill guides or jigs can elevate your accuracy. A drill guide, for instance, holds the bit steady and ensures it enters the wood at a 90-degree angle, minimizing the chance of drift. For repetitive holes, a jig—a custom-made template—can save time and maintain consistency. While these tools require an initial investment, they pay dividends in efficiency and quality, especially for intricate projects like cabinetmaking or restoration work.

Comparing traditional and modern methods reveals the evolution of hole alignment. Historically, craftsmen relied on hand-eye coordination and simple tools like awls or scribes. Today, digital aids like laser guides and smartphone apps offer real-time alignment assistance. However, the core principle remains: meticulous marking and alignment are non-negotiable. Whether you choose a high-tech approach or stick to tried-and-true methods, the goal is the same—clean, accurate holes that preserve the integrity of the old wood.

Finally, a practical tip: always test your alignment on a scrap piece of similar wood before drilling into your project. This trial run allows you to adjust markings or techniques without risking damage. For old wood, which may be brittle or prone to splintering, this step is invaluable. By treating marking and aligning as a deliberate, thoughtful process, you’ll achieve professional results that honor the character of the material while meeting functional demands.

Unveiling Amy Wood's Age: A Comprehensive Look at Her Life

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Drilling at Slow Speed

Old wood, often brittle and prone to splitting, demands a delicate touch when drilling. One of the most effective techniques to preserve its integrity is drilling at a slow speed. This method minimizes heat buildup, reduces the risk of splintering, and allows for better control over the drill bit’s penetration. High-speed drilling generates friction, which can cause the wood to crack or burn, especially in aged or dried-out timber. By slowing down, you give the material time to respond without stress, ensuring a clean and precise hole.

To implement this technique, start by selecting a drill with variable speed control. Set the RPM (revolutions per minute) to a low setting, typically between 300 and 600 RPM, depending on the wood’s condition and the bit size. For larger bits or particularly hard wood, err on the lower side. Begin drilling with gentle pressure, allowing the bit to cut through the wood gradually. If you notice resistance or hear a change in pitch, ease off slightly to prevent binding. This approach not only protects the wood but also extends the life of your drill bit by reducing wear.

A common mistake when drilling at slow speed is underestimating the importance of lubrication. Old wood, especially if it’s dry, benefits from a light application of wax or paraffin along the drill bit’s path. This reduces friction and helps the bit glide through the material. Another practical tip is to use a backing board behind the wood to prevent blowout—a common issue when drilling through thin or weakened sections. The backing board provides support, ensuring a clean exit point for the bit.

Comparing slow-speed drilling to high-speed methods highlights its advantages. While high-speed drilling is faster, it’s riskier for old wood, often leading to damage that requires repair. Slow-speed drilling, though time-consuming, is a conservative approach that prioritizes the wood’s structural integrity. It’s particularly valuable for restoration projects or working with antique furniture, where preserving the original material is crucial. The extra minutes spent drilling slowly can save hours of repair work later.

In conclusion, drilling at slow speed is a meticulous yet essential technique for working with old wood. It requires patience and attention to detail but yields superior results. By adjusting your drill’s speed, using lubrication, and employing a backing board, you can achieve clean, precise holes without compromising the wood’s stability. This method is not just a tip—it’s a principle that respects the material’s age and character, ensuring your project stands the test of time.

Natalie Wood's Age: Uncovering the Life and Legacy of a Star

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Preventing Wood Splitting

Old wood, often dried and brittle, is prone to splitting under the pressure of a drill bit. This vulnerability stems from its reduced moisture content and the natural aging process, which weakens the wood’s fibers. To counteract this, start by selecting the right drill bit. A brad-point or spade bit with a sharp, centered tip is ideal, as it creates a clean entry point and reduces the likelihood of the wood cracking. Always ensure the bit is sharp; dull bits increase friction and tearing, exacerbating the risk of splitting.

Another critical step is to pre-drill a pilot hole. Begin with a smaller bit (e.g., 1/8 inch) to create a guide hole before using the full-sized bit. This technique minimizes stress on the wood fibers and provides a pathway for the larger bit to follow. For particularly stubborn or aged wood, consider using a screw or nail to manually create a starter hole. This low-tech approach can be surprisingly effective in preventing splits, especially in delicate or antique pieces.

Applying moisture to the drilling area can temporarily restore some of the wood’s flexibility. Lightly dampen the spot with a cloth or sponge 10–15 minutes before drilling. Avoid over-saturating, as excessive moisture can cause swelling or warping. This method is particularly useful for extremely dry or cracked wood, as it helps the fibers resist splitting under pressure.

Finally, control your drilling speed and pressure. High-speed drilling generates heat, which can further dry out the wood and increase the risk of splitting. Use a slow, steady pace and let the bit do the work. Apply gentle, consistent pressure, and stop immediately if you feel resistance. If the wood begins to crack, withdraw the bit, reassess your approach, and consider reinforcing the area with wood glue or a backing board before retrying.

By combining these strategies—the right bit, pilot holes, moisture application, and controlled drilling—you can significantly reduce the risk of splitting when working with old wood. Each step addresses a specific vulnerability of aged timber, ensuring your project remains intact and structurally sound.

Unveiling Lolo Wood's Age: A Surprising Discovery About Her Life

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Lubricating the Drill Bit

Drilling through old wood can be a test of patience and precision, but lubricating the drill bit can transform this task from a grueling chore into a smooth operation. The friction generated by drilling, especially in dense or aged wood, causes heat buildup, which can dull the bit and splinter the material. Lubrication reduces this friction, preserving both the tool and the workpiece. Common lubricants include cutting oil, wax sticks, or even household items like soap or paraffin wax. Applying a small amount directly to the bit or the drilling surface can make a noticeable difference in performance.

Consider the type of lubricant based on the wood’s condition and the project’s scale. For small tasks, a wax-based lubricant like a candle or beeswax rubbed along the bit’s flutes suffices. For larger projects or particularly hard wood, a cutting oil or specialized drilling lubricant is more effective. Apply sparingly—a few drops or a thin coating is enough. Over-lubrication can attract dust and create a messy residue, defeating the purpose. Always wipe excess lubricant from the bit and surrounding area before drilling to maintain control and cleanliness.

The technique of application matters as much as the lubricant itself. For handheld drills, dip the bit into the lubricant or use a brush to coat the flutes evenly. For stationary drills or drill presses, apply the lubricant directly to the drilling spot, ensuring it penetrates the wood fibers. Reapply as needed, especially when drilling deeper holes or encountering resistance. This proactive approach minimizes heat and friction, allowing the bit to glide through the wood rather than forcing its way, which reduces the risk of cracking or burning.

While lubricating the drill bit is a simple step, its impact on the outcome is significant. It extends the life of the bit by reducing wear and tear, ensures cleaner holes without splintering, and speeds up the drilling process. For old wood, which is often brittle or prone to splitting, this method is particularly crucial. Pairing lubrication with a sharp, appropriately sized bit and moderate drilling speed creates optimal conditions for success. Think of it as giving your tools and materials the care they need to perform at their best.

Seamless Secrets: How Ancient Wooden Boats Stayed Watertight

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

For old wood, use a sharp, high-speed steel (HSS) or carbide-tipped drill bit. These materials are durable enough to handle the hardness and potential brittleness of aged wood.

To prevent splitting, use a pilot hole by starting with a smaller drill bit, then gradually increase the size. Additionally, place a piece of scrap wood behind the drilling area to support the exit point and reduce tear-out.

When drilling old, brittle wood, go slow and apply steady, light pressure to avoid cracking. Using a backing board and sharp bit is crucial, and consider using a lubricant like beeswax or drilling oil to reduce friction and heat buildup.